Abstract

Inheritance is typically associated with the Mendelian transmission of information from parents to offspring by alleles (DNA sequence). However, empirical data clearly suggest that traits can be acquired from ancestors by mechanisms that do not involve genetic alleles, referred to as non-genetic inheritance. Information that is non-genetically transmitted across generations includes parental experience and exposure to certain environments, but also parental mutations and polymorphisms, because they can change the parental ‘intrinsic’ environment. Non-genetic inheritance is not limited to the first generation of the progeny, but can involve the grandchildren and even further generations. Non-genetic inheritance has been observed for multiple traits including overall development, cardiovascular risk and metabolic symptoms, but this review will focus on the inheritance of behavioral abnormalities pertinent to psychiatric disorders. Multigenerational non-genetic inheritance is often interpreted as the transmission of epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation and chromatin modifications, via the gametes (transgenerational epigenetic inheritance). However, information can be carried across generations by a large number of bioactive substances, including hormones, cytokines, and even microorganisms, without the involvement of the gametes. We reason that this broader definition of non-genetic inheritance is more appropriate, especially in the context of psychiatric disorders, because of the well-recognized role of parental and early life environmental factors in later life psychopathology. Here we discuss the various forms of non-genetic inheritance in humans and animals, as well as rodent models of psychiatric conditions to illustrate possible mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The traditional view that Mendelian inheritance can fully explain heritability is no longer satisfactory (Bonduriansky, 2012). Several lines of evidence indicate the existence of multiple mechanisms that underlie the acquisition and transmission of traits across generations (Figure 1). Non-genetic inheritance could partly explain ‘missing heritability’, the discrepancy between the high heritability of complex disorders, and the small number of identified risk genes associated with those disorders (Manolio et al, 2009; Slatkin, 2009). In principle, non-genetic inheritance comprises all parent–offspring mechanisms of inheritance, except the transmission of alleles (DNA sequence variants). While non-genetic inheritance is typically associated with parental experience or environment, it is important to acknowledge that parental mutations and genetic variability, by altering the parental ‘intrinsic’ environment, can also result in a phenotype that is transmitted non-genetically to the genetically unaffected offspring (Figure 1).

Multiple pathways of transmitting non-genetic information across generations.

The most plausible mechanism of transmitting information across generations is via the gametes, referred to as ‘gametic non-genetic inheritance’ (Figure 1). Although this mode of non-genetic inheritance is typically believed to be transmitted by epigenetic signatures, such as secondary DNA and chromatin modifications, identifying epigenetic alterations in the germline, that are propagated to the embryo and adult offspring, remains elusive. Nevertheless, carriers of parental information in the gametes may include RNA and prions, in addition to DNA methylation and chromatin modifications. Recent data also demonstrate that non-gametic inheritance occurs via parental hormones, immune molecules, and even microorganisms (Howerton and Bale, 2012) (Figure 1). Still other non-gametic mechanisms of inheritance are social or behavioral transmission of phenotypes, a topic extensively covered in previous reviews (Meaney, 2001; Champagne and Meaney, 2007; Cameron et al, 2008), as well as in this issue.

In contrast to genetic inheritance, non-genetic inheritance typically affects only a limited number of generations, from a single to a few. Although an evolutionary role for non-genetic inheritance has been implicated (Danchin et al, 2011; Day and Bonduriansky, 2011; Hunter et al, 2012), its limited transmission is more consistent with an adaptive, also called programming, function (Agrawal et al, 1999; Dantzer et al, 2013). According to this hypothesis, non-genetic inheritance would exert its effects by providing information on the parental environment to the offspring (and to a few generations of descendants) during development to increase their fitness (eg, survival and reproduction). This idea can be extended to include disease that occurs either when adaptive programming is disrupted (for example by a maternal genetic mutation) or when the response initially facilitates survival, but carries consequent tradeoffs manifested as diseases (Frankenhuis and Del Giudice, 2012).

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FOR THE PROPAGATION OF NON-GENETIC BEHAVIORAL EFFECTS ACROSS GENERATIONS IN HUMAN

Effect of the Environment

It is now well established that maternal malnutrition, infection, stress, and psychiatric conditions are associated with an increased incidence of behavioral abnormalities in children manifested at adolescent/adult age. For example, children of women pregnant during the Dutch famine in WWII, besides being smaller than normal at birth, had behavioral abnormalities (Hoek et al, 1998; Painter et al, 2005). Similarly, adult children of Holocaust survivors have increased risk for anxiety and higher levels of psychological distress (Scharf, 2007; Gangi et al, 2009). Also, maternal infection during pregnancy, especially when it requires hospitalization, has repeatedly been associated with a higher incidence of autism and schizophrenia in the progeny (Patterson, 2009; Brown, 2012; Zerbo et al, 2013).

Parental effects are not limited to the first generation (F1) offspring and can be extended to the grandchildren (F2) (Lumey et al, 2011). Studies showed a higher than normal vulnerability of the adult grandchildren of Holocaust survivors to psychological distress (Sigal et al, 1988; Scharf, 2007). Similarly, a higher incidence of poor health in later life of grandchildren of mothers who suffered from the Dutch famine during pregnancy was also reported (Painter et al, 2008).

Effect of Parental Psychiatric Conditions

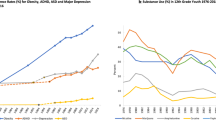

A number of reports have found a direct correlation between parental psychiatric disease and the presence of psychopathology in the offspring. Although genetic inheritance is difficult to exclude in these studies, heritability is higher than expected based on known gene variants in complex diseases (see missing heritability above), indicating that non-genetic inheritance may account partly for the missing components. For example, maternal posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increases the risk for PTSD in the offspring (Yehuda et al, 2008; Roberts et al, 2012) and maternal antenatal anxiety is associated with behavioral problems in young children (O'Connor et al, 2002) as well as with hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation and depressive symptoms in adolescent children (Van den Bergh et al, 2008). Similarly, maternal depression and social phobia are associated with increased incidence of child psychopathology (Tillfors et al, 2001; Weissman and Jensen, 2002; Halligan et al, 2004; Huizink et al, 2004; Halligan et al, 2007; Brummelte and Galea, 2010; Murray et al, 2010). Furthermore, another study investigated the effect of depression on prepubertal psychopathology in two generations of offspring, particularly on anxiety (anxiety, in contrast to depression, often has a prepubertal onset), and found that grandparent and parent major depression is associated with prepubertal anxiety (Weissman and Jensen, 2002). The highest risk for anxiety in the grandchildren was associated with both parental and grandparental depression, while grandchildren with only parental, but not grandparental depression, had the lowest risk, suggesting that grandparental depression has a higher impact on children anxiety risk than depression in the parent.

Limitations in Studying Non-Genetic Inheritance in Human

Information about the behavioral effects of the environment on consecutive generations in humans is limited and so far spans only three generations. In addition, all human studies are correlative, precluding the study of the underlying mechanism of non-genetic inheritance. For example, it is difficult, if not impossible to determine whether the information transfer between parents, children, and grandchildren is based on behavioral interactions or the transfer of hormones or other substances via the placenta or milk, or whether it is mediated by the inheritance of epigenetic marks via the gametes. Distinguishing between these possibilities and identifying the contribution of non-genetic inheritance to phenotypes require animal models (discussed below).

An additional complication is that the child or grandchild condition can be due to the shared exposure with the parents and grandparents that would not qualify for non-genetic inheritance. This confound can be excluded if the parental and grandparental conditions are known to be terminated before the birth of the child.

NON-GENETIC INHERITANCE IN ANIMAL MODELS

Non-genetic inheritance across single or multiple generations was originally observed in animals, both in the wild (Agrawal et al, 1999) and in the laboratory (Harper, 2005; Whitelaw and Whitelaw, 2008; Bohacek et al, 2013). Rodents in particular, due to their widespread use and their well-established genetics and embryo transfer techniques, are suitable models to study non-genetic inheritance at the mechanistic level.

Effect of Stress, Abused Drugs and Toxins Across Generations

The initial trigger of non-genetic inheritance is often an external environmental factor, such as limited calorie intake, infection, stress, drugs of abuse and toxins, resulting in an adverse gestational environment that leads to behavioral abnormalities in the offspring (Veenema et al, 2008; Chen et al, 2011). Many of these effects are multigenerational and here we discuss examples that report on transmission to at least the F2 generation.

Parental and postnatal stress is a well known factor in causing behavioral abnormalities in the offspring. For example, stress during pregnancy results in increased activity in the F2 generation (Wehmer et al, 1970). Maternal malnutrition and synthetic glucocorticoid administration alter HPA axis functions in both the F1 and F2 generations, that can lead to stress-related behavioral phenotypes (Kostaki et al, 2005; Bertram et al, 2008). In some models, stress exposure of the female results in transmission to the F2 generation, but only through F1 males (Morgan and Bale, 2011; Saavedra-Rodriguez and Feig, 2012), suggesting male gamete-mediated F1 to F2 transmission. Maternal separation during early postnatal development results in behavioral deficits in the F1 offspring that are transmitted to the F2 generation through females (Weiss et al, 2011). Finally, mice exposed to chronic social stress during adolescence and early adulthood exhibit persistent behavioral alterations, including enhanced anxiety and social deficits (Saavedra-Rodríguez and Feig, 2013). Although both exposed mothers and fathers can transmit the altered behaviors to their female F1 offspring, only F1 fathers transmit them to their F2 and F3 daughters.

Drug abuse is another environmental trigger of multigenerational behavioral effects. The first reports that drugs may have behavioral effects beyond the exposed individual and across generations came from studies showing that offspring of males exposed to opiates, cocaine, and alcohol have increased anxiety and impaired spatial learning (Abel et al, 1989; Ledig et al, 1998; He et al, 2006). More recently, it was demonstrated that offspring of female rats exposed to morphine during adolescence have alterations in recognition memory, anxiety-like behavior, and social interaction, as well as in opiate sensitivity and tolerance (Byrnes, 2005a, 2005b, Byrnes, 2008; Byrnes et al, 2011). Interestingly, some of these effects were further transmitted to the F2 generation (Byrnes et al, 2013). A similar heritable phenotype, resulting from the self-administration of cocaine, was also described in rats (Vassoler et al, 2013). The phenotype included delayed acquisition and reduced maintenance of cocaine self-administration in male, but not female, offspring of sires that self-administered cocaine. Whether this phenotype is transmitted to further generations was not reported. Similarly, parental exposure to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive component of cannabis, resulted in increased work effort to self-administer heroin in the F1 generation (Szutorisz et al, 2014). As both parents were exposed to THC, whether the transmission occurs via male or female is not known.

Some environmental toxins, such as endocrine disruptors, are able to affect not only the exposed individual but the subsequent, and even consecutive, generations. Exposure during gestation to diethylstilbestrol (DES), an agent with estrogen agonist activity, produces reproductive tract dysfunctions in both the F1 and F2 generations (Newbold et al, 2006). The anti-androgenic endocrine disruptor flutamide causes testicular abnormalities in the F1 and skeletal developmental problems in the F2 generation (Anway et al, 2005). The effect of another endocrine disruptor, the fungicide vinclozolin, which has anti-androgenic endocrine actions, is extended to the F3 generation and beyond (Anway et al, 2005; Anway et al, 2006). Exposure of rats to this toxin during the second week of pregnancy, which is the critical period of gonadal sex differentiation in the fetus, produces impaired spermatogenesis in the F1 and up to the F4 generation. Interestingly, additional phenotypes, including decreased anxiety in F3 males and increased anxiety in F3 females were also reported (Skinner et al, 2008). The different behavioral effects in males and females are not unusual and reflect the gender-specific manifestations of non-genetically acquired phenotypes, similarly to those that are caused by genetic or direct environmental factors (McCarthy et al, 2012).

Maternal Mutations and Genetic Variability as Intrinsic Environmental Factors in Non-Genetic Inheritance

While the previous section discussed the effect of the external environment on the parents, and in turn, on the offspring, this section summarizes published data on how parental genetic variability, as an intrinsic factor, can alter the behavior of their offspring via a non-genetic mechanism (ie, ancestral genotype effect). As single genetic mutations are easier to control and standardize within and across experiments, in addition to the fact that they represent a more specific starting point in mechanistic studies than the external environment, mutation-based models may provide an advantage in deciphering the non-genetic transfer of information from mutant parents to genetically unaffected offspring.

It was reported that the genetically wild-type (WT) offspring of Dnmt1a (DNA methyltransferase) and SMARCA5 (SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin) heterozygote fathers exhibit transcriptional changes and chromosome ploidy in adulthood (Chong et al, 2007). As these proteins are essential in DNA methylation and chromatin remodeling, their haploinsufficiency may disrupt epigenetic reprogramming in the male gametes resulting in the offspring phenotypes. Also, we reported that the genetic inactivation of one or both alleles of the serotonin (5-HT)1A receptor (5-HT1AR) results in an anxiety-like phenotype in the mother, characterized by the avoidance of open areas in preference for safe areas, reduced exploration in large spaces, and increased reactivity in unavoidable stress situations. Furthermore, these three hallmarks of anxiety are transmitted to their WT F1 offspring. Some of the anxiety-related behaviors were also transmitted to the F2 and F3 generations (Laird and Toth, unpublished). Finally, a recent study showed that a hypomorphic mutation in the enzyme methionine synthase reductase (Mtrr) in the dams, that is necessary for the utilization of methyl groups from the folate cycle, results in various congenital malformations, including neuronal tube defects in the maternal grand progeny (Padmanabhan et al, 2013). Some of these defects persisted for five generations.

Genetic/epigenetic variability in the parents can also be a source of non-genetic transmission. Individual females with high and low maternal care (defined as individuals’ 1 SD above and below the group mean, respectively) were selected from an outbred rat population and the anxiety phenotype of their offspring was followed. While the offspring of mothers with low level of care attain anxiety, when they are cross-fostered at birth to mothers with high level of care acquire a low level of anxiety (Caldji et al, 1998; Liu et al, 2000). Although it is not entirely clear whether the variability in maternal care was due to genetic, environmental, or stochastic epigenetic differences, these experiments indicate that the transmission is non-genetic. This cycle of non-genetic inheritance is repeated across generations (Francis et al, 1999). Another similar experiment utilized two inbred strains of mice with differing anxiety levels. Embryo transfer and cross-fostering (Figure 2) demonstrated the non-genetic transmission of high anxiety phenotype, characteristic for the BALB strain, to B6 offspring, that normally exhibit low anxiety, during the period that encompassed both gestation and early postnatal life (Francis et al, 2003).

Embryo transfer, in vitro fertilization (IVF) and cross-fostering can distinguish between gametic and non-gametic prenatal and non-gametic postnatal mechanisms of non-genetic inheritance.

MECHANISMS UNDERLYING THE PROPAGATION OF NON-GENETIC EFFECTS ACROSS GENERATIONS

The transmission of parental experience across generations could be based on several different mechanisms. The most plausible mode of information transfer is via the gametes. However, parental experience can be passed through the placenta and milk to the fetus/neonate via biologically active molecules whose effects reconstitute the parental phenotype. This process is repeated in the next generation, perpetuating the parental phenotype via a non-gametic mechanism. Embryo transfer and/or cross-fostering experiments can distinguish non-gametic prenatal and postnatal transfer of information from that of gamete-mediated non-genetic inheritance (Figure 2). Offspring, derived from matings of unaffected parents, should exhibit the phenotype when transferred as embryos or cross-fostered as newborns to affected mothers/parents, if the transmission occurred during gestation or postnatally, respectively (Figure 2a). For example, WT mice implanted as 1-day-old embryos into 5-HT1AR-deficient mothers and then cross-fostered at birth to WT mothers exhibited anxiety mentioned above, indicating that the non-genetic transfer occurred during gestation (Gleason et al, 2010). Similarly, embryo transfer experiments demonstrated that the effects of the maternal Mtt mutation are transferred to their WT offspring non-genetically during the gestation period (Padmanabhan et al, 2013). These experiments also excluded the possibility that the offspring phenotype was caused by ‘spurious’ gene mutations or genetic polymorphisms; unequivocally demonstrating non-genetic inheritance. In contrast, offspring generated by in vitro fertilization (IVF) or from early embryos derived from affected parent(s) and implanted to unaffected mothers should display the phenotype if the transmission is gametic (Figure 2b).

Environmental Effects Perpetuated via ‘Non-Gametic’ Transmission during the Prenatal and Early Postnatal Period

Molecular substrates carrying information from mother to offspring

Somatic cells, for example neurons in the developing brain, can acquire properties during fetal or early postnatal life from their parents, in particular from their mother (but also from their father), via the transfer of bioactive molecules. These bioactive substrates include hormones, cytokines, immune cells, and even parental microorganisms (Howerton and Bale, 2012) (Figure 1). For example, stress during pregnancy results in increased levels of glucocorticoids that can alter the HPA axis and the stress response of the offspring (Koehl et al, 1999). Although the placenta expresses the enzyme 11-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD), which under normal conditions converts the glucocorticoids into inactive products (Reynolds, 2013), high levels of maternal circulating glucocorticoids can reach the fetal brain (Zarrow et al, 1970). Moreover, stress can reduce placental HSD, which further facilitates maternal glucocorticoids to reach the fetus (Mairesse et al, 2007). Increased maternal glucocorticoid levels sensitize the various neuroendocrine systems, most significantly the HPA axis, increasing stress-induced glucocorticoid secretion (Peters, 1982; Henry et al, 1994) and prolonging their secretion (Fride et al, 1986; Maccari et al, 1995; Barbazanges et al, 1996). In general, the neuroendocrine changes are accompanied by increased anxiety and depression-like behaviors (Vallée et al, 1997), altered locomotor activity (Maccari et al, 2003), and impaired spatial learning (Ishiwata et al, 2005) in the offspring. As the physiological adaptation of the offspring to prenatal stress recapitulates the maternal stress response, the effect may be further transmitted (Matthews and Phillips, 2010). Indeed, glucocorticoid administration during gestation resulted in altered HPA function in F2 females and hippocampal glucocorticoid feedback in both F2 males and females (Iqbal et al, 2012).

Cytokines could also transmit information from mother to offspring, and perhaps to additional generations. For example, excess levels of maternal interleukin 6 can reprogram the offspring brain and lead to behavioral abnormalities that resemble some of the symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (Smith et al, 2007; Patterson, 2009; Malkova et al, 2012). Also, we have shown that maternal tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) levels alter the spatial memory of the offspring (Liu et al, 2014).

Still another potential pathway of the mother to offspring communication involves microorganisms. At birth, the gastrointestinal tract (GI) of neonates is sterile and is gradually colonized through exposure to the maternal microbiota (vaginal, fecal, oral, and dermal) (Curtis and Sloan, 2004). Colonization occurs in a succession by various bacterial species that leads to a final mature microbiota whose composition has a significant effect on brain functioning and behavior. For example, maternal/perinatal stress reduces Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species in the gut microbiome and results in increased stress reactivity and anxiety in the offspring, while ingestion of Lactobacillus has the opposite effect (Sudo et al, 2004; Gareau et al, 2007; Desbonnet et al, 2010; Bravo et al, 2011). The gut microbiome may communicate with the brain via the immune system, the vagus nerve, or by changing the permeability of the GI track affecting the adsorption of food and bacteria-derived products (Fåk et al, 2008; Bravo et al, 2011; Al-Asmakh et al, 2012; Hooper et al, 2012; Nicholson et al, 2012). As stress and environmental influences alter the composition of the gut microbiome and because the offspring gut microbiome is derived from their mothers, microbiome-associated psychopathology could be perpetuated across generations.

Relevance to psychiatric disorders

Similarly to the results obtained in animal experiments, exposure to excess glucocorticoids during prenatal life in humans alters the functioning of the HPA axis and the stress response of the offspring. For example, paired maternal–fetal and maternal–cord blood samples show positive correlation indicating that high cortisol in the mother is associated with high cortisol in the fetus and newborn (Gitau et al, 2004; Smith et al, 2011). High mid/late gestation maternal cortisol levels are also correlated with higher cortisol response to stress in the newborn. The increased HPA activity, as a result of higher than normal intrauterine cortisol, persists into adulthood (Phillips et al, 2000). Intrauterine exposure to excess maternal cortisol can be due not only to maternal stress but also to loss of function mutations in HSD (Dave-Sharma et al, 1998). Still another example of environmentally induced exposure to excess cortisol in human occurs when pregnant woman at risk of preterm delivery are treated with synthetic glucocorticoids to promote fetal lung development. Although studying the behavioral effects of excess prenatal glucocorticoid is complicated by confounds such as premature birth, accumulating data suggest permanent behavioral problems in these children that include increased distractibility and inattention (French et al, 1999), impaired cognitive development and narrative memory, and increased risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Räikkönen et al, 2009; Bergman et al, 2010). This process may be perpetuated across generations and could explain the higher vulnerability of adult grandchildren of mothers exposed to extreme stress to psychological distress (Sigal et al, 1988; Scharf, 2007) and depression (Weissman and Jensen, 2002).

Non-Genetic Inheritance via the Gametes

It is typical to think of non-genetic inheritance as gametic transmission of traits with an epigenetic basis. However, most environmentally acquired epigenetic marks, even if introduced into the germline, do not typically propagate to consecutive generations. Nevertheless, there is evidence that some epigenetic marks can be passed from one to next generation. Also, the original interpretation of epigenetic information embedded in DNA methylation and chromatin modifications has been expanded to include other molecules, including RNA and prions, which may have a higher probability to be passed along generations via the gametes.

DNA methylation and chromatin modifications as possible carriers of transgenerational information

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosines, typically in a CG, but also in CA, CT, or CC context. While the majority of CG sites are methylated, there are areas with reduced or no methylation, such as CG islands (CGIs). Also, regions can have tissue-specific methylation differences. Maintenance methylation in principle provides a mechanism ensuring that methylation is not lost during mitotic cell divisions. The DNA is associated with histones that have their own heritable secondary modifications (Turner, 2007). DNA methylation, in conjunction with DNA bound histones, controls the accessibility of transcription factors and cofactors to the DNA; thus modulating gene expression (Bird, 2002).

Reprogramming in the germline and early embryo

Although not all, most information embedded in DNA methylation and histone modification is typically not passed to the next generation, because of reprogramming. In mammals, two major waves of reprogramming occur; one in the primordial germ cells (PGCs, the progenitors of oocytes and sperm) and another in the early embryo. Reprogramming is best understood in the mouse and involves the genome-wide erasure and subsequent establishment of DNA methylation and histone modification profiles, at each of the two reprogramming events (Rose et al, 2013).

DNA demethylation occurs between embryonic (E) day 8 and 12.5 in PGCs, while they migrate toward the genital ridge. Demethylation occurs simultaneously in both males and females and is accompanied by a reduction in the repressive mark H3K9 dimethylation (me2) and an increase in another repressive mark H3K27 trimethylation (me3). The reciprocal relationship between these modifications may facilitate the maintenance of repression patterns during epigenetic reprogramming. Demethylation seems to occur via conversion to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, driven by high levels of tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 and 2 (TET 1 and 2), and completed by replication-coupled dilution (Seisenberger et al, 2012; Hackett et al, 2013). By E13.5, replication of germs cells and reprogramming are completed. Female germ cells enter meiosis I, but are halted at prophase I, persisting as primary oocytes until menarche, while male germ cells undergo mitotic arrest and stay at this stage until puberty. From puberty, oocytes and sperm are produced through meiosis. Global methylation in the sperm and oocyte is 90% and 40%, respectively (Kobayashi et al, 2012). While methylation in sperm is mostly limited to repetitive elements and intergenic sequences with relatively few methylated CGIs, the oocyte has more than a thousand methylated CGIs (Borgel et al, 2010; Smallwood et al, 2011; Kobayashi et al, 2012; Smith et al, 2012).

The second phase of reprogramming occurs in the early embryo. Active demethylation in the zygote, involving extensive hydroxymethylation (paternal allele), is followed by the passive loss of methylation (both paternal and maternal alleles) during early cell divisions. Subsequently, remethylation takes place during the transition from blastocyst to epiblast (Smith et al, 2012).

Escape from erasure

Although reprogramming is genome wide and extensive during female PGC development (Seisenberger et al, 2012; Seisenberger et al, 2013), 4730 loci were shown to escape demethylation, predominantly repeat sequences (>95%), including IAP elements (intracisternal A particle) of the family of endogenous retrovirus (ERV) elements (Hackett et al, 2013). In addition to repeat sequences, 11 single loci at methylated CGIs were found to escape reprogramming in female E13.5 PGCs (Hackett et al, 2013). Another study found a subset of ERV1 elements and 23 single loci, of which 19 are not flanked by IAPs and have no apparent repeat sequences, to resist demethylation, in both male and female E13.5 PGCs (Guibert et al, 2012). Importantly, erasure-resistant single loci typically also retain their methylation in the early embryo (Guibert et al, 2012; Seisenberger et al, 2012). Although these loci are potential candidates for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, the environmental malleability of their methylation or chromatin structure is not known.

Although sequences that are resistant to germline erasure typically also escape reprogramming in the early embryo (providing a possible substrate for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance), there are additional methylated sequences in the zygote that survive reprogramming in the early embryo. These include imprinted sequences and most of the oocyte and a few sperm-specific methylated CGIs (Smith et al, 2012). Another study identified ∼100 non-repeat and non-imprinted gene promoters whose methylation is not erased during early development (Borgel et al, 2010). These single locus sequences could mediate the gametic transmission of traits to the F2 generation, via the maternal line, because environmental exposure of the pregnant female could affect not only the F1 embryo, but also the F2, already reprogrammed, primary oocytes. As these methylation marks are typically erased in the germline, the traits would not be transmitted to the F3 generation. This ‘F2-specific’ epigenetic mechanism may explain the observation that some phenotypes can skip the F1 generation or can be stronger in the F2 than in the F1 generation, seen in both humans and in animal models (Wehmer et al, 1970; Weissman and Jensen, 2002).

Some nucleosomes may also escape removal during reprogramming, even in sperm, in which most of the histones are replaced by protamines. These reprogramming-resistant sperm nucleosomes are enriched in H2K27me3 and it has been suggested that this histone modification may represent a paternally transmitted transgenerational signal (Hammoud et al, 2009; Brykczynska et al, 2010).

Evidence for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

Currently, non-genetic inheritance of traits has not been linked directly to gametic epigenetic marks that persist to the embryo and somatic tissues and then appear in the next generation germ cells. However, a number of reports described gamete-mediated transmission of behavior accompanied by epigenetic marks in the gametes and brain of the progeny. In a series of now classical papers, it was shown that transcription at the agouti-viable yellow and axin-fused loci is regulated by the methylation status of embedded IAP elements, which drives the phenotypes; a range of coat colors from yellow (low methylation/high expression) to brown (high methylation/low expression) for agouti and kinky tail (low methylation/high expression) for axin fused (Morgan et al, 1999; Rakyan and Whitelaw, 2003; Rakyan et al, 2003; Blewitt et al, 2006). The methylation status of the IAP at the parental agouti-viable yellow and axin-fused loci is recapitulated in the somatic cells of the offspring (in the maternal and in both the paternal and maternal offspring, respectively). As IAP elements are typically resistant to germline and early embryonic erasure, it was expected that methylation at the agouti-viable yellow and axin-fused alleles survive reprogramming, demonstrating that methylated DNA can be the carrier of intergenerational information. However, the IAP elements at both loci were found to be completely demethylated in blastocysts, derived from mothers carrying the methylated epialleles, indicating that methylation is not the epigenetic mark that carries the information across generations (Blewitt et al, 2006; Fernandez-Gonzalez et al, 2010). Then, it has been hypothesized that histone marks represent the epigenetic memory that survive erasure at these loci, because the penetrant (kinky tail) and silent axin-fused epialleles were associated with differences in histone H3K4 me2 and H3K9 ac marks at the blastocyst stage (Fernandez-Gonzalez et al, 2010).

Importantly, the agouti-viable yellow and axin-fused loci are environmentally malleable, because their methylation can be increased and the number of yellow and kinky tailed offspring decreased by maternal diet rich in methyl donors (folic acid, betaine, vitamin B12) (Wolff et al, 1998; Waterland and Jirtle, 2003; Cropley et al, 2006; Waterland et al, 2006). However, whether these diet-induced methylation changes are transgenerational is debated, as one report found no evidence for transmission (Waterland et al, 2007) while another described the appearance of the maternal phenotype in the next generation (Cropley et al, 2006).

In a recent paper, transmission of paternal sensitivity (startle response) to a specific odor, established by odor–shock pairing before mating, was reported through the paternal line to at least two consecutive generations (Dias and Ressler, 2013). Reduced DNA methylation was seen at the stimulus-associated odor receptor gene (Olfr151) in the sperm of both the exposed father and his naïve F1 offspring. Although these experiments do not establish a causal relationship between hypomethylation at Olfr151 in sperm and the non-genetic inheritance of odor sensitivity, the phenotype was transmitted even following in vitro fertilization and cross-fostering, indicating that some information in the gametes are linked to the non-genetic inheritance of the behavioral phenotype.

A similar situation is exemplified by maternal separation that leads to depressive-like behaviors in the adult F1 (stressed) offspring, manifested as deficits in novelty response, risk assessment, and social behaviors (Franklin et al, 2010; Weiss et al, 2011). These behaviors are transmitted through both the male and female lines up to the third generation and are accompanied by DNA methylation changes at stress-related gene promoters in F1 sperm and F2 brains. Likewise, paternal cocaine administration results in reduced sensitivity to the drug in the male offspring that is accompanied by altered histone 3 acetylation at the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene in the sperm of the exposed father and in the brain of the offspring. In addition, expression of BDNF mRNA and protein was increased in the medial prefrontal cortex of the offspring (Vassoler et al, 2013). As inhibition of BDNF signaling reversed the phenotype, the epigenetic change in sperm and its presence in progeny brain may be directly related to the transmission of behavioral phenotype. Finally, in a model of fetal alcohol syndrome, it was shown that offspring, exposed during gestation to alcohol, exhibit a deficit in proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-related functions (for example stress hormone expression), accompanied by increased CpG methylation in the POMC promoter (Govorko et al, 2012) and that suppression of DNA methylation can normalize the functional abnormalities. Fetal alcohol-induced DNA methylation and functional defects persisted in the F2 and F3 male, but not in female, and promoter hypermethylation was detected in sperm of fetal alcohol-exposed F1 offspring that was transmitted through F3 generation via male germline. However, the ultimate proof to establish transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in all of these experiments is to rescue the transmitted phenotype by normalizing the environmentally induced epigenetic change in sperm. Although this approach is challenging, it is now feasible with recently developed site-directed genome-editing technologies.

RNA as carrier of transgenerational information

RNAs represent a new group of ‘substrates’ that could carry information across multiple generations via the gametes. The first data suggesting an RNA-mediated transgenerational effect in mammals was the identification of abnormal transcripts in sperm, produced from a structurally modified Kit parental allele (encoding a tyrosine kinase receptor), that resulted in a ‘white tail’ phenotype in the genetically WT offspring across multiple generations (Rassoulzadegan et al, 2006). Microinjection of total parental RNA into fertilized eggs reproduced the phenotype indicating that RNA was the carrier of phenotypic information. As this ‘paramutation’-like phenomenon in the mouse involves engineered mutations in the parental allele, the significance of this finding could be limited. However, two microRNAs with sequences partially complementary to that of Kit RNA (miR-221 and -222) induced the paramutated state (Rassoulzadegan et al, 2006). Moreover, a screen for paramutagenic miRNAs identified miR-1 and miR-124 causing paramutation-like effects on Cdk9 or Sox9 manifested as transgenerational cardiac hypertrophy and accelerated embryonic growth, respectively (Wagner et al, 2008; Grandjean et al, 2009; Cuzin and Rassoulzadegan, 2010). Interestingly, the mir-124-related phenotype was related to the establishment of a distinct, heritable chromatin structure in the promoter region of Sox9 (Grandjean et al, 2009). Overall, these data indicate that sperm, and presumably oocyte, miRNAs can be passed to the embryo resulting in gene expression (Bartel, 2009) and phenotypic changes in the developing and adult progeny.

The possible role of RNAs in transmitting behavioral phenotypes is just beginning to be explored. One example is related to the non-genetic inheritance of increased stress responsiveness induced by maternal gestational stress in two consecutive generations of males (Mueller and Bale, 2008). The transmission of the stress phenotype was accompanied by reductions in miR-322, miR-574, and miR-873 in the brain and increased expression of their common target, β-glycan (TGFβr3) (Morgan and Bale, 2011). In a similar study, naïve males, rather than pregnant females, were exposed to chronic stress during puberty or in adulthood, which led to significantly reduced HPA stress axis responsivity in their offspring (Rodgers et al, 2013). The sperm miRNA content of stressed males was significantly altered with a total of nine miRNA increased. However, it is currently not known if the stress-induced miRNA profile is directly responsible for the reprogramming of the HPA axis. Another group of small RNAs, potentially relevant to transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, is represented by germ cell PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) (Luteijn and Ketting, 2013), but their involvement in non-genetic transmission of behavior is not yet known.

Future Research Directions

In conclusion, beyond the fundamental scientific interest in understanding how behavioral variability can propagate across generations via a non-genetic route, non-genetic inheritance has translational significance, because even a short period of parental exposure can increase the risk for neuropsychiatric disease in consecutive generations. Information transfer between generations can occur through multiple mechanisms. Although the most conceivable way of non-genetic inheritance is via the gametes, only a limited number of studies show unequivocally that gametes are the carriers of this information. Indeed, experiments employing embryo transfer or in vitro fertilization are required to prove that the phenotype is transmitted via the gametes (Figure 2). Unfortunately, very few studies actually employed these techniques and therefore, third and fourth generation traits described in the literature are not necessarily gamete mediated. The epigenome is reprogrammed through gametogenesis and in the early embryo, and only few traits are likely to be truly epigenetic in nature, therefore warranting a cautious interpretation. In principle, there are two requirements for a molecule or molecular modification to carry epigenetic information across several generations. First, it has to be associated with the parental gametes (whether in the nucleus, cytoplasm or even structures associated with the gametes) and be stable enough to survive until fertilization. Second, the molecule/molecular modification or its signal has to be propagated through embryogenesis and then through gametogenesis and reprogramming. A number of molecules may be suitable carriers of epigenetic inheritance, including secondary DNA and histone modifications and small RNAs. Non-gametic inheritance is equally complicated mechanistically, as multiple parental–offspring pathways exist with very different molecular and cellular basis. These mechanisms include social/behavioral, immunological, and microbial interactions. Similar to the gametic non-genetic inheritance, rigorous standards are required to establish non-gametic inheritance because the possible confounds of spurious genetic effects. For example, toxin-induced mutations in the parents or spurious parental mutations, that are transmitted genetically, could underlie the transmission of a trait. To exclude these genetic confounds, the best practice is to transfer early embryos or cross-foster newborns from unaffected parents to mothers/parents exposed to the environmental factor, depending on whether the effect is pre- or postnatal, respectively. It is expected that both non-gametic and gametic non-genetic inheritance contribute to the high incidence of psychiatric disorders. Therefore, one may also expect that the two forms of non-genetic inheritance carry symptom-specific information simultaneously that, together with genetic traits, will explain the complex and variable phenotypes of psychiatric disorders. The varying mechanisms of inheritance may call for different preventive measures and could influence the strategies employed to prevent and possibly mitigate disease symptoms.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURE

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Abel EL, Moore C, Waselewsky D, Zajac C, Russell LD (1989). Effects of cocaine hydrochloride on reproductive function and sexual behavior of male rats and on the behavior of their offspring. J Androl 10: 17–27.

Agrawal AA, Laforsch C, Tollrian R (1999). Transgenerational induction of defences in animals and plants. Nature 401: 60–63.

Al-Asmakh M, Anuar F, Zadjali F, Rafter J, Pettersson S (2012). Gut microbial communities modulating brain development and function. Gut Microbes 3: 366–373.

Anway MD, Cupp AS, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK (2005). Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science 308: 1466–1469.

Anway MD, Memon MA, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK (2006). Transgenerational effect of the endocrine disruptor vinclozolin on male spermatogenesis. J Androl 27: 868–879.

Barbazanges A, Piazza PV, Le Moal M, Maccari S (1996). Maternal glucocorticoid secretion mediates long-term effects of prenatal stress. J Neurosci 16: 3943–3949.

Bartel DP (2009). MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233.

Bergman K, Sarkar P, Glover V, O'Connor TG (2010). Maternal prenatal cortisol and infant cognitive development: moderation by infant-mother attachment. Biol Psychiatry 67: 1026–1032.

Bertram C, Khan O, Ohri S, Phillips DI, Matthews SG, Hanson MA (2008). Transgenerational effects of prenatal nutrient restriction on cardiovascular and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. J Physiol 586: 2217–2229.

Bird A (2002). DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 16: 6–21.

Blewitt ME, Vickaryous NK, Paldi A, Koseki H, Whitelaw E (2006). Dynamic reprogramming of DNA methylation at an epigenetically sensitive allele in mice. PLoS Genet 2: e49.

Bohacek J, Gapp K, Saab BJ, Mansuy IM (2013). Transgenerational epigenetic effects on brain functions. Biol Psychiatry 73: 313–320.

Bonduriansky R (2012). Rethinking heredity, again. Trends Ecol Evol 27: 330–336.

Borgel J, Guibert S, Li Y, Chiba H, Schubeler D, Sasaki H et al (2010). Targets and dynamics of promoter DNA methylation during early mouse development. Nat Genet 42: 1093–1100.

Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG et al (2011). Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 16050–16055.

Brown AS (2012). Epidemiologic studies of exposure to prenatal infection and risk of schizophrenia and autism. Dev Neurobiol 72: 1272–1276.

Brummelte S, Galea LA (2010). Depression during pregnancy and postpartum: contribution of stress and ovarian hormones. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 34: 766–776.

Brykczynska U, Hisano M, Erkek S, Ramos L, Oakeley EJ, Roloff TC et al (2010). Repressive and active histone methylation mark distinct promoters in human and mouse spermatozoa. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 679–687.

Byrnes EM (2005a). Transgenerational consequences of adolescent morphine exposure in female rats: effects on anxiety-like behaviors and morphine sensitization in adult offspring. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 182: 537–544.

Byrnes EM (2005b). Chronic morphine exposure during puberty decreases postpartum prolactin secretion in adult female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 80: 445–451.

Byrnes EM (2008). Chronic morphine exposure during puberty induces long-lasting changes in opioid-related mRNA expression in the mediobasal hypothalamus. Brain Res 1190: 186–192.

Byrnes JJ, Babb JA, Scanlan VF, Byrnes EM (2011). Adolescent opioid exposure in female rats: transgenerational effects on morphine analgesia and anxiety-like behavior in adult offspring. Behav Brain Res 218: 200–205.

Byrnes JJ, Johnson NL, Carini LM, Byrnes EM (2013). Multigenerational effects of adolescent morphine exposure on dopamine D2 receptor function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 227: 263–272.

Caldji C, Tannenbaum B, Sharma S, Francis D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ (1998). Maternal care during infancy regulates the development of neural systems mediating the expression of fearfulness in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 5335–5340.

Cameron NM, Shahrokh D, Del Corpo A, Dhir SK, Szyf M, Champagne FA et al (2008). Epigenetic programming of phenotypic variations in reproductive strategies in the rat through maternal care. J Neuroendocrinol 20: 795–801.

Champagne FA, Meaney MJ (2007). Transgenerational effects of social environment on variations in maternal care and behavioral response to novelty. Behav Neurosci 121: 1353–1363.

Chen GH, Wang H, Yang QG, Tao F, Wang C, Xu DX (2011). Acceleration of age-related learning and memory decline in middle-aged CD-1 mice due to maternal exposure to lipopolysaccharide during late pregnancy. Behav Brain Res 218: 267–279.

Chong S, Vickaryous N, Ashe A, Zamudio N, Youngson N, Hemley S et al (2007). Modifiers of epigenetic reprogramming show paternal effects in the mouse. Nat Genet 39: 614–622.

Cropley JE, Suter CM, Beckman KB, Martin DI (2006). Germ-line epigenetic modification of the murine A vy allele by nutritional supplementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 17308–17312.

Curtis TP, Sloan WT (2004). Prokaryotic diversity and its limits: microbial community structure in nature and implications for microbial ecology. Curr Opin Microbiol 7: 221–226.

Cuzin F, Rassoulzadegan M (2010). Non-Mendelian epigenetic heredity: gametic RNAs as epigenetic regulators and transgenerational signals. Essays Biochem 48: 101–106.

Danchin E, Charmantier A, Champagne FA, Mesoudi A, Pujol B, Blanchet S (2011). Beyond DNA: integrating inclusive inheritance into an extended theory of evolution. Nat Rev Genet 12: 475–486.

Dantzer B, Newman AE, Boonstra R, Palme R, Boutin S, Humphries MM et al (2013). Density triggers maternal hormones that increase adaptive offspring growth in a wild mammal. Science 340: 1215–1217.

Dave-Sharma S, Wilson RC, Harbison MD, Newfield R, Azar MR, Krozowski ZS et al (1998). Examination of genotype and phenotype relationships in 14 patients with apparent mineralocorticoid excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 2244–2254.

Day T, Bonduriansky R (2011). A unified approach to the evolutionary consequences of genetic and nongenetic inheritance. Am Nat 178: E18–E36.

Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Kiely B, Cryan JF, Dinan TG (2010). Effects of the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis in the maternal separation model of depression. Neuroscience 170: 1179–1188.

Dias BG, Ressler KJ (2013). Parental olfactory experience influences behavior and neural structure in subsequent generations. Nat Neurosci 17: 89–96.

Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Ramirez MA, Pericuesta E, Calle A, Gutierrez-Adan A (2010). Histone modifications at the blastocyst Axin1(Fu) locus mark the heritability of in vitro culture-induced epigenetic alterations in mice. Biol Reprod 83: 720–727.

Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney MJ (1999). Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science 286: 1155–1158.

Francis DD, Szegda K, Campbell G, Martin WD, Insel TR (2003). Epigenetic sources of behavioral differences in mice. Nat Neurosci 6: 445–446.

Frankenhuis WE, Del Giudice M (2012). When do adaptive developmental mechanisms yield maladaptive outcomes? Dev Psychol 48: 628–642.

Franklin TB, Russig H, Weiss IC, Gräff J, Linder N, Michalon A et al (2010). Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations. Biol Psychiatry 68: 408–415.

French NP, Hagan R, Evans SF, Godfrey M, Newnham JP (1999). Repeated antenatal corticosteroids: size at birth and subsequent development. Am J Obstet Gynecol 180: 114–121.

Fride E, Dan Y, Feldon J, Halevy G, Weinstock M (1986). Effects of prenatal stress on vulnerability to stress in prepubertal and adult rats. Physiol Behav 37: 681–687.

Fåk F, Ahrné S, Molin G, Jeppsson B, Weström B (2008). Microbial manipulation of the rat dam changes bacterial colonization and alters properties of the gut in her offspring. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G148–G154.

Gangi S, Talamo A, Ferracuti S (2009). The long-term effects of extreme war-related trauma on the second generation of Holocaust survivors. Violence Vict 24: 687–700.

Gareau MG, Jury J, MacQueen G, Sherman PM, Perdue MH (2007). Probiotic treatment of rat pups normalises corticosterone release and ameliorates colonic dysfunction induced by maternal separation. Gut 56: 1522–1528.

Gitau R, Fisk NM, Glover V (2004). Human fetal and maternal corticotrophin releasing hormone responses to acute stress. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 89: F29–F32.

Gleason G, Liu B, Bruening S, Zupan B, Auerbach A, Mark W et al (2010). The serotonin1A receptor gene as a genetic and prenatal maternal environmental factor in anxiety. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 7592–7597.

Govorko D, Bekdash RA, Zhang C, Sarkar DK (2012). Male germline transmits fetal alcohol adverse effect on hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin gene across generations. Biol Psychiatry 72: 378–388.

Grandjean V, Gounon P, Wagner N, Martin L, Wagner KD, Bernex F et al (2009). The miR-124-Sox9 paramutation: RNA-mediated epigenetic control of embryonic and adult growth. Development 136: 3647–3655.

Guibert S, Forné T, Weber M (2012). Global profiling of DNA methylation erasure in mouse primordial germ cells. Genome Res 22: 633–641.

Hackett JA, Sengupta R, Zylicz JJ, Murakami K, Lee C, Down TA et al (2013). Germline DNA demethylation dynamics and imprint erasure through 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Science 339: 448–452.

Halligan SL, Herbert J, Goodyer IM, Murray L (2004). Exposure to postnatal depression predicts elevated cortisol in adolescent offspring. Biol Psychiatry 55: 376–381.

Halligan SL, Murray L, Martins C, Cooper PJ (2007). Maternal depression and psychiatric outcomes in adolescent offspring: a 13-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 97: 145–154.

Hammoud SS, Nix DA, Zhang H, Purwar J, Carrell DT, Cairns BR (2009). Distinctive chromatin in human sperm packages genes for embryo development. Nature 460: 473–478.

Harper LV (2005). Epigenetic inheritance and the intergenerational transfer of experience. Psychol Bull 131: 340–360.

He F, Lidow IA, Lidow MS (2006). Consequences of paternal cocaine exposure in mice. Neurotoxicol Teratol 28: 198–209.

Henry C, Kabbaj M, Simon H, Le Moal M, Maccari S (1994). Prenatal stress increases the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis response in young and adult rats. J Neuroendocrinol 6: 341–345.

Hoek HW, Brown AS, Susser E (1998). The Dutch famine and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33: 373–379.

Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ (2012). Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336: 1268–1273.

Howerton CL, Bale TL (2012). Prenatal programing: at the intersection of maternal stress and immune activation. Horm Behav 62: 237–242.

Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, Buitelaar JK (2004). Prenatal stress and risk for psychopathology: specific effects or induction of general susceptibility? Psychol Bull 130: 115–142.

Hunter B, Hollister JD, Bomblies K (2012). Epigenetic inheritance: what news for evolution? Curr Biol 22: R54–R56.

Iqbal M, Moisiadis VG, Kostaki A, Matthews SG (2012). Transgenerational effects of prenatal synthetic glucocorticoids on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Endocrinology 153: 3295–3307.

Ishiwata H, Shiga T, Okado N (2005). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment of early postnatal mice reverses their prenatal stress-induced brain dysfunction. Neuroscience 133: 893–901.

Kobayashi H, Sakurai T, Imai M, Takahashi N, Fukuda A, Yayoi O et al (2012). Contribution of intragenic DNA methylation in mouse gametic DNA methylomes to establish oocyte-specific heritable marks. PLoS Genet 8: e1002440.

Koehl M, Darnaudéry M, Dulluc J, Van Reeth O, Le Moal M, Maccari S (1999). Prenatal stress alters circadian activity of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and hippocampal corticosteroid receptors in adult rats of both gender. J Neurobiol 40: 302–315.

Kostaki A, Owen D, Li D, Matthews SG (2005). Transgenerational effects of prenatal glucocorticoid exposure on growth, endocrine function and behaviour in the guinea pig. Pediatr Res 58: P1–052.

Ledig M, Misslin R, Vogel E, Holownia A, Copin JC, Tholey G (1998). Paternal alcohol exposure: developmental and behavioral effects on the offspring of rats. Neuropharmacology 37: 57–66.

Liu B, Zupan B, Laird E, Klein S, Gleason G, Bozinoski M et al (2014). Maternal hematopoietic TNF, via milk chemokines, programs hippocampal development and memory. Nat Neurosci 17: 97–105.

Liu D, Diorio J, Day JC, Francis DD, Meaney MJ (2000). Maternal care, hippocampal synaptogenesis and cognitive development in rats. Nat Neurosci 3: 799–806.

Lumey LH, Stein AD, Susser E (2011). Prenatal famine and adult health. Annu Rev Public Health 32: 237–262.

Luteijn MJ, Ketting RF (2013). PIWI-interacting RNAs: from generation to transgenerational epigenetics. Nat Rev Genet 14: 523–534.

Maccari S, Piazza PV, Kabbaj M, Barbazanges A, Simon H, Le Moal M (1995). Adoption reverses the long-term impairment in glucocorticoid feedback induced by prenatal stress. J Neurosci 15: 110–116.

Maccari S, Darnaudery M, Morley-Fletcher S, Zuena AR, Cinque C, Van Reeth O (2003). Prenatal stress and long-term consequences: implications of glucocorticoid hormones. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27: 119–127.

Mairesse J, Lesage J, Breton C, Bréant B, Hahn T, Darnaudéry M et al (2007). Maternal stress alters endocrine function of the fetoplacental unit in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E1526–E1533.

Malkova NV, Yu CZ, Hsiao EY, Moore MJ, Patterson PH (2012). Maternal immune activation yields offspring displaying mouse versions of the three core symptoms of autism. Brain Behav Immun 26: 607–616.

Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ et al (2009). Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461: 747–753.

Matthews SG, Phillips DI (2010). Minireview: transgenerational inheritance of the stress response: a new frontier in stress research. Endocrinology 151: 7–13.

McCarthy MM, Arnold AP, Ball GF, Blaustein JD, De Vries GJ (2012). Sex differences in the brain: the not so inconvenient truth. J Neurosci 32: 2241–2247.

Meaney MJ (2001). Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 1161–1192.

Morgan CP, Bale TL (2011). Early prenatal stress epigenetically programs dysmasculinization in second-generation offspring via the paternal lineage. J Neurosci 31: 11748–11755.

Morgan HD, Sutherland HG, Martin DI, Whitelaw E (1999). Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat Genet 23: 314–318.

Mueller BR, Bale TL (2008). Sex-specific programming of offspring emotionality after stress early in pregnancy. J Neurosci 28: 9055–9065.

Murray L, Halligan SL, Goodyer I, Herbert J (2010). Disturbances in early parenting of depressed mothers and cortisol secretion in offspring: a preliminary study. J Affect Disord 122: 218–223.

Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Jefferson WN (2006). Adverse effects of the model environmental estrogen diethylstilbestrol are transmitted to subsequent generations. Endocrinology 147: S11–S17.

Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, Burcelin R, Gibson G, Jia W et al (2012). Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 336: 1262–1267.

O'Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Beveridge M, Glover V (2002). Maternal antenatal anxiety and children's behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Br J Psychiatry 180: 502–508.

Padmanabhan N, Jia D, Geary-Joo C, Wu X, Ferguson-Smith AC, Fung E et al (2013). Mutation in folate metabolism causes epigenetic instability and transgenerational effects on development. Cell 155: 81–93.

Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, Bleker OP (2005). Prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine and disease in later life: an overview. Reprod Toxicol 20: 345–352.

Painter RC, Osmond C, Gluckman P, Hanson M, Phillips DI, Roseboom TJ (2008). Transgenerational effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on neonatal adiposity and health in later life. BJOG 115: 1243–1249.

Patterson PH (2009). Immune involvement in schizophrenia and autism: etiology, pathology and animal models. Behav Brain Res 204: 313–321.

Peters DA (1982). Prenatal stress: effects on brain biogenic amine and plasma corticosterone levels. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 17: 721–725.

Phillips DI, Walker BR, Reynolds RM, Flanagan DE, Wood PJ, Osmond C et al (2000). Low birth weight predicts elevated plasma cortisol concentrations in adults from 3 populations. Hypertension 35: 1301–1306.

Rakyan V, Whitelaw E (2003). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Curr Biol 13: R6.

Rakyan VK, Chong S, Champ ME, Cuthbert PC, Morgan HD, Luu KV et al (2003). Transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic states at the murine Axin(Fu) allele occurs after maternal and paternal transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 2538–2543.

Rassoulzadegan M, Grandjean V, Gounon P, Vincent S, Gillot I, Cuzin F (2006). RNA-mediated non-mendelian inheritance of an epigenetic change in the mouse. Nature 441: 469–474.

Reynolds RM (2013). Glucocorticoid excess and the developmental origins of disease: two decades of testing the hypothesis—2012 Curt Richter Award Winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 1–11.

Roberts AL, Galea S, Austin SB, Cerda M, Wright RJ, Rich-Edwards JW et al (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder across two generations: concordance and mechanisms in a population-based sample. Biol Psychiatry 72: 505–511.

Rodgers AB, Morgan CP, Bronson SL, Revello S, Bale TL (2013). Paternal stress exposure alters sperm microRNA content and reprograms offspring HPA stress axis regulation. J Neurosci 33: 9003–9012.

Rose CM, van den Driesche S, Meehan RR, Drake AJ (2013). Epigenetic reprogramming: preparing the epigenome for the next generation. Biochem Soc Trans 41: 809–814.

Räikkönen K, Pesonen AK, Heinonen K, Lahti J, Komsi N, Eriksson JG et al (2009). Maternal licorice consumption and detrimental cognitive and psychiatric outcomes in children. Am J Epidemiol 170: 1137–1146.

Saavedra-Rodriguez L, Feig LA (2012). Chronic social instability induces anxiety and defective social interactions across generations. Biol Psychiatry 73: 44–53.

Saavedra-Rodríguez L, Feig LA (2013). Chronic social instability induces anxiety and defective social interactions across generations. Biol Psychiatry 73: 44–53.

Scharf M (2007). Long-term effects of trauma: psychosocial functioning of the second and third generation of Holocaust survivors. Dev Psychopathol 19: 603–622.

Seisenberger S, Peat JR, Hore TA, Santos F, Dean W, Reik W (2013). Reprogramming DNA methylation in the mammalian life cycle: building and breaking epigenetic barriers. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368: 20110330.

Seisenberger S, Andrews S, Krueger F, Arand J, Walter J, Santos F et al (2012). The dynamics of genome-wide DNA methylation reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Mol Cell 48: 849–862.

Sigal JJ, DiNicola VF, Buonvino M (1988). Grandchildren of survivors: can negative effects of prolonged exposure to excessive stress be observed two generations later? Can J Psychiatry 33: 207–212.

Skinner MK, Anway MD, Savenkova MI, Gore AC, Crews D (2008). Transgenerational epigenetic programming of the brain transcriptome and anxiety behavior. PLoS One 3: e3745.

Slatkin M (2009). Epigenetic inheritance and the missing heritability problem. Genetics 182: 845–850.

Smallwood SA, Tomizawa S, Krueger F, Ruf N, Carli N, Segonds-Pichon A et al (2011). Dynamic CpG island methylation landscape in oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Nat Genet 43: 811–814.

Smith AK, Jeffrey Newport D, Ashe MP, Brennan PA, Laprairie JL, Calamaras M et al (2011). Predictors of neonatal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity at delivery. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 75: 90–95.

Smith SE, Li J, Garbett K, Mirnics K, Patterson PH (2007). Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J Neurosci 27: 10695–10702.

Smith ZD, Chan MM, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Gnirke A, Regev A et al (2012). A unique regulatory phase of DNA methylation in the early mammalian embryo. Nature 484: 339–344.

Sudo N, Chida Y, Aiba Y, Sonoda J, Oyama N, Yu XN et al (2004). Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol 558: 263–275.

Szutorisz H, Dinieri JA, Sweet E, Egervari G, Michaelides M, Carter JM et al (2014). Parental THC exposure leads to compulsive heroin-seeking and altered striatal synaptic plasticity in the subsequent generation. Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 1315–1323.

Tillfors M, Furmark T, Ekselius L, Fredrikson M (2001). Social phobia and avoidant personality disorder as related to parental history of social anxiety: a general population study. Behav Res Ther 39: 289–298.

Turner BM (2007). Defining an epigenetic code. Nat Cell Biol 9: 2–6.

Vallée M, Mayo W, Dellu F, Le Moal M, Simon H, Maccari S (1997). Prenatal stress induces high anxiety and postnatal handling induces low anxiety in adult offspring: correlation with stress-induced corticosterone secretion. J Neurosci 17: 2626–2636.

Van den Bergh BR, Van Calster B, Smits T, Van Huffel S, Lagae L (2008). Antenatal maternal anxiety is related to HPA-axis dysregulation and self-reported depressive symptoms in adolescence: a prospective study on the fetal origins of depressed mood. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 536–545.

Vassoler FM, White SL, Schmidt HD, Sadri-Vakili G, Pierce RC (2013). Epigenetic inheritance of a cocaine-resistance phenotype. Nat Neurosci 16: 42–47.

Veenema AH, Reber SO, Selch S, Obermeier F, Neumann ID (2008). Early life stress enhances the vulnerability to chronic psychosocial stress and experimental colitis in adult mice. Endocrinology 149: 2727–2736.

Wagner KD, Wagner N, Ghanbarian H, Grandjean V, Gounon P, Cuzin F et al (2008). RNA induction and inheritance of epigenetic cardiac hypertrophy in the mouse. Dev Cell 14: 962–969.

Waterland RA, Jirtle RL (2003). Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol 23: 5293–5300.

Waterland RA, Travisano M, Tahiliani KG (2007). Diet-induced hypermethylation at agouti viable yellow is not inherited transgenerationally through the female. FASEB J 21: 3380–3385.

Waterland RA, Dolinoy DC, Lin JR, Smith CA, Shi X, Tahiliani KG (2006). Maternal methyl supplements increase offspring DNA methylation at Axin Fused. Genesis 44: 401–406.

Wehmer F, Porter RH, Scales B (1970). Pre-mating and pregnancy stress in rats affects behaviour of grandpups. Nature 227: 622.

Weiss IC, Franklin TB, Vizi S, Mansuy IM (2011). Inheritable effect of unpredictable maternal separation on behavioral responses in mice. Front Behav Neurosci 5: 3.

Weissman MM, Jensen P (2002). What research suggests for depressed women with children. J Clin Psychiatry 63: 641–647.

Whitelaw NC, Whitelaw E (2008). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in health and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 18: 273–279.

Wolff GL, Kodell RL, Moore SR, Cooney CA (1998). Maternal epigenetics and methyl supplements affect agouti gene expression in Avy/a mice. FASEB J 12: 949–957.

Yehuda R, Bell A, Bierer LM, Schmeidler J (2008). Maternal, not paternal, PTSD is related to increased risk for PTSD in offspring of Holocaust survivors. J Psychiatr Res 42: 1104–1111.

Zarrow MX, Philpott JE, Denenberg VH (1970). Passage of 14C-4-corticosterone from the rat mother to the foetus and neonate. Nature 226: 1058–1059.

Zerbo O, Qian Y, Yoshida C, Grether JK, Van de Water J, Croen LA (2013). Maternal Infection during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord (e-pub ahead of print).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by US National Institute of Mental Health grant 1RO1MH080194, 5R01MH058669 and 5R01MH086883 to MT.

Glossary

(some definitions may differ from those used in other reviews)

Inheritance. The process by which phenotypes (traits or characters) are passed from parents to offspring.

Non-genetic inheritance. Inheritance is typically associated with genetic or Mendelian inheritance. However, traits can be passed from parents to offspring via mechanisms that do not involve the DNA sequence. Therefore, inheritance is a broader term that includes non-genetic mechanisms of inheritance.

Gamete. A mature male or female germ cell that fuses with a gamete of the opposite sex during fertilization.

Epigenetic marks/signatures. In addition to the DNA sequence, gene expression information is embedded in additional layers on the DNA, termed epigenetic marks/signatures. Cells acquire epigenetic marks during their development. Epigenetic marks include chemical modifications of the DNA and secondary modifications in histones. Small RNAs are also often viewed as epigenetic signals/signatures because, a priori, any mechanism that provides regulatory information to a genome could be considered epigenetic. In contrast to the DNA sequence, epigenetic marks are malleable by the environment and their changes by the environment can significantly alter the cellular phenotype. In fact, it is believed that adaptation to the environment, learning, and many environmentally related processes involve changes in the epigenetic state of alleles.

Epialleles. Alleles those are identical in sequence, but different in epigenetic modifications.

Non-genetic inheritance via the gametes. A form of non-genetic inheritance that is mediated by the gametes without the involvement of DNA sequence. As epigenetic marks in the gametes are believed to carry the information from parents to offspring, this mechanism is also referred to as ‘transgenerational epigenetic inheritance’. However, any biological compound within or associated with the gametes, excluding the DNA sequence, may serve as a carrier of non-genetic information.

Gestational and early postnatal non-genetic inheritance. A process that involves the transfer of traits from the mother to offspring during gestation, or from the parents to the offspring during the early postnatal period, which typically spans from birth to weaning. It is also called ‘maternal/parental programming’. Mother/father information transfer can occur via the immune system, metabolites, and the microbiome, but also through social/behavioral interaction.

Multigenerational non-genetic effects. The acquisition and propagation of novel phenotypes across multiple generations that are not genetically based.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toth, M. Mechanisms of Non-Genetic Inheritance and Psychiatric Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol 40, 129–140 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.127

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.127

This article is cited by

-

Global DNA methylation changes in adults with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and its comorbidity with bipolar disorder: links with polygenic scores

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

Mendel’s laws of heredity on his 200th birthday: What have we learned by considering exceptions?

Heredity (2022)

-

Exposure to maternal high-fat diet induces extensive changes in the brain of adult offspring

Translational Psychiatry (2021)

-

Behavioral changes and brain epigenetic alterations induced by maternal deficiencies of B vitamins in a mouse model

Psychopharmacology (2021)

-

Drug-seeking motivation level in male rats determines offspring susceptibility or resistance to cocaine-seeking behaviour

Nature Communications (2017)