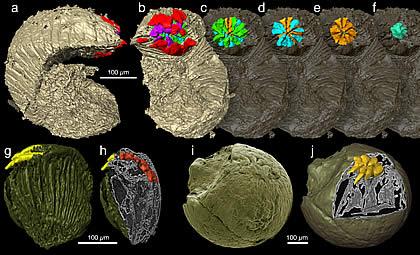

A glimpse inside a 500 million year-old embryo.Credit: Philip Donoghue and colleagues

A glimpse inside a 500 million year-old embryo.Credit: Philip Donoghue and colleaguesResearchers have snuck an unprecedented glimpse at the dawn of multicellular life.

Using techniques borrowed from medicine and particle physics, palaeontologists have reconstructed the three-dimensional structure of tiny fossilized embryos that are more than 500 million years old.

Philip Donoghue from the University of Bristol, UK, and colleagues used a technique called synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM) to investigate the fossilized embryos of ancient worm-like species that lived during the Cambrian Period — the time when most modern animal groups first appear in the fossil record.

The embryos, which are less than a millimetre across, have been well studied since their discovery in China and Siberia several decades ago. But researchers have either used scanning electron microscopy to study their surface, or chopped the fossils into thin slices in order to study the interior using light microscopy.

Donoghue's team is the first to peer inside the embryos without destroying them in the process. And they get extremely detailed results to boot.

The researchers took their samples to the Swiss Light Source, a huge doughnut-shaped particle accelerator at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Villigen, Switzerland. X-rays from the synchrotron pass through the specimen and are caught on camera. The process is then repeated hundreds of times as the sample is gradually rotated through 180 degrees. A computer finally reconstructs the colourful 3D image.

Inside out

The team reveal the internal structures of embryos in various phases of development, from an early blob of dividing cells to a more complex stage with different, specialized cell types. Individual cells can be seen in exquisite detail, and structures less than one thousandth of a millimetre across can be made out.

"The resolution of internal detail is staggering," says palaeobiologist Simon Conway Morris from the University of Cambridge, UK, who studies the early evolution of animal life.

One embryo, of a species called Pseudooides prima, seems to have a unique way of growing body segments during development — they form in the middle of the creature rather than at the extremities of its body.

A detailed view of Markuelia, apparently a distant relative of the modern-day penis worm.Credit: Philip Donoghue and colleagues

A detailed view of Markuelia, apparently a distant relative of the modern-day penis worm.Credit: Philip Donoghue and colleaguesAnother, known as Markuelia, was previously thought to be some sort of worm, insect or armoured slug. But the 3D reconstruction reveals that the specimen has an anus at one end and a mouth at the other, which contains rows of teeth arranged in rings of five. This particular dental plan confirms that the animal is a distant relative of the modern-day priapulid or penis worm, says Donoghue.

Fake fossils

The detailed images also make it possible to pick out genuine biological form from artefact and may shed light on another controversial fossil find — the Doushantuo fossils from southwest China.

The Doushantuo fossils, which predate Cambrian specimens by tens of millions of years, are an eclectic mix of early marine animal and plant life. But some think that a selection of these fossils formed from inorganic crystals rather than from biological structures.

The SRXTM images are so detailed that it is relatively easy to pick out artefacts, some of which resemble features seen in the Doushantuo fossils, the researchers say. This suggests that certain Doushantuo relics, including presumed developing embryos and tiny bilateral animals, are artefacts rather than true fossils.

ADVERTISEMENT

This is important because it suggests that the major evolutionary diversification of animals may not, as some have suggested, begun before the Cambrian period.

"It's a very cool article," says Bernie Degnan from the University of Queensland, Australia, who studies the evolution of body shape. "The method has the potential to help reconstruct the earliest steps in metazoan [animal] evolution."

Visit our peerinsidefossilembry.html">newsblog to read and post comments about this story.