The quake struck off the coast of Tonga in the early hours of the morning of 4 May, during a power cut on the island.© NOAA

The quake struck off the coast of Tonga in the early hours of the morning of 4 May, during a power cut on the island.© NOAAA precautionary tsunami warning was issued on 3 May (GMT) for Tonga and the nearby South Pacific, after a 7.8 earthquake struck off the coast of that island. Thankfully the quake didn't trigger a large wave, and both Tonga and the surrounding coasts were spared devastating damage. But the event tested the newly revamped Pacific tsunami warning system, which did fairly well to disseminate the information — with a few glitches.

"It was a nice exercise," says Gerard Fryer, a geophysicist who was acting head of the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Ewa Beach, Hawaii, when this quake struck. This is the same centre that issued a warning of the lethal December 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean.

“We have discovered a couple of glitches.”

Gerard Fryer

Pacific Tsunami Warning Center

In the aftermath of that catastrophe, people were startled to learn that the PTWC, the place best equipped to detect and announce the wave, was staffed by a handful of people who had to bicycle furiously from home if their beepers went off. Three of its six scientific buoys — meant to detect tsunami waves in the deep ocean by the pressure they produce on the sea floor — were broken. The team also had no official list of people to call beyond the Pacific if they did suspect a tsunami was threatening. When the wave struck, more than 186,000 people are known to have died.

A dedicated Indian Ocean tsunami warning system is now on the cards. And, just a few days ago, the US National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration announced that a series of improvements have been made to the Pacific system, the fruits of two years of work and millions of extra dollars from the US government. Since the week before this latest earthquake, the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center has been staffed round the clock.

Early morning tremor

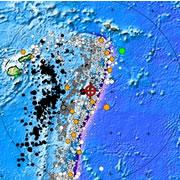

The epicentre of the quake (red cross), surrounded by previous quakes (circles, sized according to magnitude of the tremor). The coloured circles indicate quakes that have generated tsunamis, with orange meaning no damage was caused, green for local damage.© NOAA

The epicentre of the quake (red cross), surrounded by previous quakes (circles, sized according to magnitude of the tremor). The coloured circles indicate quakes that have generated tsunamis, with orange meaning no damage was caused, green for local damage.© NOAAWhen the quake hit, at 4:27 on 4 May Tonga time (15:27 on 3 May GMT), a flood of data from seismic networks indicated that the earthquake was of about magnitude 8 and fairly shallow - the kind of tremor that could trigger a tsunami. Forty-two sea-level stations and 14 scientific buoys belonging to the centre were operational at the time around the Pacific. One of these buoys, and one from another network, picked up signs of the event, according to Theresa Eisenman, a spokeswoman from the NOAA.

By 4:42 local time, the first warning bulletin was on its way out to the world. At 5:31, a bulletin was sent saying that a wave, if generated, should have already arrived in Tonga and could hit Fiji some hour-and-a-half later. But a simple tide gauge on Niue island, about 500 kilometres east of the earthquake, showed just a tiny 40-centimetre surge from a long-wavelength 'tsunami'. This convinced the PTWC that no giant wave was going to be produced. The all-clear was sounded at 6:36.

ADVERTISEMENT

"Everything went well, although we have discovered a couple of glitches," says Fryer. Because of a bug somewhere, not everyone who should have received the first of three bulletins did. And although that first warning was properly sent to the emergency services centre in Tonga, the centre was in the midst of a power outage, so the news of a possible killer wave did not reach Tongans very quickly.

It was hotel night staff watching CNN who sounded the alarm on Tonga, according to Fryer. Afterwards a reporter from CNN suggested that the warning centre make a point of letting the 24-hour cable network know about these events, since it turned out to be such a good disseminator of the alert. "It is not a bad idea," says Fryer.

Visit our runfortsunamiwarning_sy.html">newsblog to read and post comments about this story.

Pacific Tsunami Warning Center