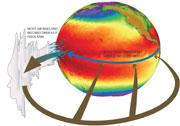

Walker circulation drives winds across the Pacific. Click here to see details.© Illustration by G. Vecchi, UCAR

Walker circulation drives winds across the Pacific. Click here to see details.© Illustration by G. Vecchi, UCARClimate change is weakening a vast system of circulating winds that traverses the Pacific Ocean from coast to coast, say climate experts. Global warming has caused the system, which is crucial for monsoon rains in Southeast Asia and fisheries in South America, to decline since the advent of industrial times.

The system, known as the Walker circulation, has weakened by more than 3% since the mid-nineteenth century, report climate modellers led by Gabriel Vecchi of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Princeton, New Jersey. The cause, they say, is greenhouse gases. And with emissions still climbing, Pacific winds could potentially decline by more than 10% by the end of the century, they predict.

The observations, reported in Nature1, back up climate model predictions that these winds should weaken, says Vecchi. "This is one of the most robust predictions of climate research," he says.

Variations in the Walker circulation are one of the factors that lead to El Niño climate events. These periodic events, which feature a weakening of the easterly winds that blow from the Americas to Southeast Asia, have a range of effects, from droughts in Indonesia to poor fish harvests in Chile.

Short-term climate fluctuations give rise to an El Niño event every few years. But an overall weakening of the Walker system could cause an increase in the severity or frequency of these events, and some experts even fear that the Pacific could be plunged into a permanent El Niño.

Wet and wild

Global warming can disrupt winds because the rate of evaporation from the ocean increases more rapidly with increasing temperatures than does the rate of precipitation. Usually, in the Walker circulation, water evaporates from the warm waters of the eastern Pacific and travels across on the trade winds to Southeast Asia, where it rises and feeds rain. The dry air then heads east again at a higher altitude, completing the cycle (see graphic).

But as sea temperatures rise, the increase in rainfall cannot keep pace with the increase in evaporation. This means that moist air gets stalled, and the winds in both directions weaken.

Vecchi and his colleagues studied records of sea-level atmospheric pressure from 1861 to 1992. Because winds are driven by differences in atmospheric pressure, the difference between pressures on the two sides of the Pacific indicates the strength of the winds. The data show a decline in winds of around 3%, they found, with the trend most marked over roughly the last 50 years of the study.

They also used computer climate models to simulate the past and future performance of the Walker circulation, helping to work out how much of the effect is due to man-made greenhouse emissions. The answer, says Vecchi, is pretty much all of it. "At least 80% of this is attributable to human activities," he says.

When the researchers ran the model without including human factors such as industrial greenhouse emissions, the change in wind strength all but disappeared. "Over the past 140 years, there should have been next to no trend," Vecchi says.

Winds of change

ADVERTISEMENT

It's unclear exactly how this change to the Walker circulation will affect El Niño patterns, because weakening of winds is both a cause and an effect of this weather event, says Mick Kelly, a researcher at the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK. "You can't separate the chicken and egg," he says.

Models run in Kelly's lab have predicted slightly more subtle effects on the Walker circulation, such as more local eddies, which could shift the areas that experience the most drought and flooding. All the flood-vulnerable coastal villages and communities that depend on Pacific fisheries should be prepared for change, Kelly says. "At the moment we can't have enough confidence in any individual model's projections. But we can't afford to wait until the science is absolutely certain; it will be too late."

Visit our warmingweakens_pacific.html">newsblog to read and post comments about this story.

-

References

- Vecchi G. A., et al. Nature, 441. 73 - 76 (2006). | Article |