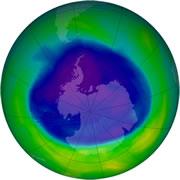

The seasonal ozone hole that developed over Antarctica this year is slightly smaller than in previous years.© NASA

The seasonal ozone hole that developed over Antarctica this year is slightly smaller than in previous years.© NASAThe Antarctic ozone hole will probably take longer to heal than was previously thought, scientists say. At the current rate of recovery, the hole won't be gone until around the year 2065, some 15 years later than the generally accepted estimate.

Research to monitor the worldwide amount of chlorofluorocarbon chemicals, or CFCs, which eat away at the protective ozone layer when released into the atmosphere, suggests that more of the chemicals are out there than expected. Modelling studies also indicate the hole will take a while to disappear.

"We're looking now at a time frame of something like 2065," said John Austin, a computer modeller at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey. He and his colleagues from several different research teams presented their ozone results on 6 December at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

Still seeping out

Production of CFCs was essentially banned under the 1987 Montreal Protocol. But some linger on in old refrigerators, fire extinguishers, air-conditioning systems and other equipment. Eventually, those chemicals will be released into the atmosphere to wreak their ozone-destroying reactions, said Dale Hurst of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Global Monitoring Division in Boulder, Colorado, also speaking on 6 December at the meeting.

A thinner atmospheric ozone layer means that more harmful ultraviolet radiation can reach the Earth's surface, potentially triggering more cases of skin cancer and other ill health effects.

Hurst's measurements of CFC emissions, taken by low-flying aeroplanes over the United States and Canada, suggest that more of the chemicals are still around than previously expected. In 2003, for instance, developed nations still accounted for almost half of the global emissions of CFCs, even though the chemicals had been banned more than a decade earlier. "We would have expected the reservoirs to be nearly exhausted," Hurst said.

Austin and his team found similar signs of a delayed recovery. Their computer models, which look at the years between 1960 and 2100, indicate that Antarctic ozone levels should return to their 1980 levels by around 2065. The Arctic ozone hole, which is smaller than the Antarctic one, could recover by as early as 2030, Austin said.

Out of our hands

Because CFCs have already been banned, the scientists present at the meeting said they had no plans to argue for further international controls on the chemicals. "I'm not sure there's a lot we can do," said Paul Newman of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

ADVERTISEMENT

The new recovery date will probably be included in the next international assessment of the ozone hole, Newman added. That assessment is due out late next year under the auspices of the World Meteorological Organization.

Also on 6 December, NASA released details of the size and extent on this year's Antarctic ozone hole. The Aura satellite measured the hole as being 24.3 million square kilometres at its largest, between September and October of this year. That is slightly larger than last year's peak, but still smaller than the 26.4-million-square-kilometre record of 1998.

<p/>