Click here to see enlarged map.© ESGS

Click here to see enlarged map.© ESGSCalifornia residents may soon have something else to ponder along with the weather forecast in their morning news. Starting this Wednesday, seismologists are providing them with earthquake forecasts too.

The quake forecasts, which are produced by adding together some of the best models of earthquake activity, aim to tell residents the probability that an earthquake big enough to smash their windows will strike in the next 24 hours. A map of these probabilities will be posted daily at http://pasadena.wr.usgs.gov/step.

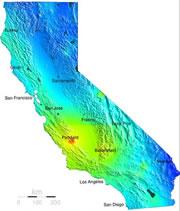

The maps show a range of danger levels, with probabilities of a quake stretching from one-in-a-million, coloured blue, to rare hot-spots shown in red, where the probability exceeds 10%.

The researchers caution that the maps don't mean that we now know how to predict earthquakes, however. The new forecasts are based on the best available knowledge, but they cannot pin down exactly where and when a quake will happen any more than researchers could do before. Given all the uncertainties surrounding earthquakes, the probabilities in the forecasts are expected to hover around the low value of 0.1% most of the time, though they can easily rise to ten times this value.

But translating all the known information about quake probabilities into a friendly format is a step forward, says forecast creator Matthew Gerstenberger of the US Geological Survey in Pasadena and his colleagues. Similar services have been available before, for a fee, from private companies such as QuakeFinder. But Gerstenberger's maps are freely and easily accessible.

"We're hoping the public will come and have a look, mainly as an educational tool to see how the hazard changes," says Gerstenberger.

Added risk

The forecast is generated by combining two types of information. First, a 'background' assessment is made of earthquake risk around California, by assessing the physical properties of various geological sites, along with the statistical behaviour of fault lines over long periods of time.

Added to this are the anticipated knock-on effects of any seismological activity that has occurred over the previous days, months or years1. This is what causes day-to-day percentages to change. This week, for example, a magnitude-4.7 aftershock in the Parkfield area, where a medium-sized quake occurred last September, has caused probabilities in the region to jump to around 1%.

The result is expressed as the chance of surface shaking exceeding level 6 on the Modified Mercalli Intensity scale - the level at which costly damage begins to occur.

Probabilities are only expected to approach high levels in the wake of a large earthquake, as this is when researchers expect aftershocks. A super-sized quake, such as that which rocked Sumatra last year, could even cause aftershock probabilities approaching 100%.

In some respects the forecasts won't contain surprising information, as most people in California know both that they are living in an area prone to earthquakes, and that a large quake is often followed by further tremors.

But the maps will show people exactly where aftershocks are most probable, as one earthquake can transfer stress onto another, neighbouring fault-line. A tenfold increase in one area thanks to a quake elsewhere will probably generate interest.

What to do?

ADVERTISEMENT

Unlike weather forecasts, where a high chance of rain may prompt people to take an umbrella with them for the day, it is unclear what people might do with earthquake forecast information. The daily percentages are too low to force any evacuations, and there is little else one can do differently on a daily basis to mitigate the risk from falling highways and buildings.

Psychologists predict that locals will take the forecasts in their stride. "I wouldn't expect any behavioural consequences to come from something like this," says Nick Pidgeon, who studies the psychology of risk at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK.

Gerstenberger hopes the maps will help remind people of the risks they live with daily. This might prompt them to take recommended actions for living in an earthquake zone - such as knowing how to turn off the gas at home, or keeping bottled water in the basement. "Anything that reminds people to do the standard safety things will be useful," he says.