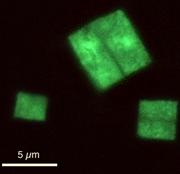

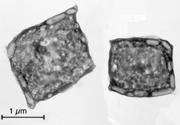

If bacteria grew on Jupiter or Ganymede, would they look like this?© Mike Dyall-Smith

If bacteria grew on Jupiter or Ganymede, would they look like this?© Mike Dyall-SmithAn unusual, square bacterium that has eluded scientists since its discovery almost 25 years ago has been grown in the lab, by two independent teams. This means researchers can finally investigate the lifestyle and physiology of what is one of the most salt-resistant microbes.

British microbiologist Anthony Walsby first scooped these salty squares out of a hypersaline pond near the Red Sea in 1980. Since then, cultivating "Walsby's square archaeon" in the lab has been a holy grail for microbiologists studying salt-loving (halophilic) bacteria.

The bacteria are around 0.15 micrometres across and have a remarkable shape, forming wafer-thin, regular tiles. "They look like postage stamps," says Henk Bolhuis, of the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, who led one of the groups and has an article in the press with Environmental Microbiology1.

To study a microbe in the lab, it is essential to be able to cultivate a plentiful supply of pure sample; it would be impractical to regularly collect fresh samples from remote locations. But despite numerous attempts, Walsby's archaeon has resisted being cultured.

"The assumption has been that it was ungrowable," says Mike Dyall-Smith, whose team at the University of Melbourne, Australia, is the first to publish a method for cultivation, in the Federation of European Microbiological Societies' Microbiology Letters2.

Salty diet

The trick was to recognize that less is more. Both Bolhuis's and Dyall-Smith's groups grew the microbe in very low concentrations of nutrients. In conditions with more nutrients, other species grow faster and swamp the slow-growing squares.

Walsby's square archaeon thrives in conditions saltier than soy sauce.© Mike Dyall-Smith

Walsby's square archaeon thrives in conditions saltier than soy sauce.© Mike Dyall-SmithThe culture needs to be hypersaline: at least 18% salt, which is roughly the same concentration as soy sauce. And the saltier the sample used to start the culture the better, because this enhances the chance that the square bacteria will have survived in greater numbers than the other microbes have.

The feat also takes plenty of patience. It took Bolhuis's team two-and-a-half years to get a pure culture. This is because the microbes grow extremely slowly, taking 1 to 2 days to double in number. By contrast, the lab workhorse Escherichia coli replicates in just 20 minutes.

Now that microbiologists have cultivated the bacterium, taxonomists can finally get on with the formalities, including giving it an official name. The Dutch group is proposing Haloquadratum walsbyi, in honour of its discoverer. It remains to be determined whether there are multiple species or strains of the microbe.

And for halophile enthusiasts, the result opens the door to exploring supersalty microbe communities. "It's an exciting breakthrough for studying the ecosystem," says Dyall-Smith.

The microbe is also extremely tolerant of magnesium chloride. According to Bolhuis, this makes it a model organism for studying what life might be like in extraterrestrial corners of the solar system, such as the magnesium-rich brines on Jupiter's moons Europa and Ganymede.