A female worm (Osedax frankpressi). The greenish roots normally burrow into whalebone, while the pink tendrils sweep microscope males into her egg sac.© Greg Rouse

A female worm (Osedax frankpressi). The greenish roots normally burrow into whalebone, while the pink tendrils sweep microscope males into her egg sac.© Greg RouseTwo worm species discovered in the dark recesses of the deep sea could rival the macabre beasts of your childhood nightmares. Scientists have named a new genus, Osedax, which is Latin for "bone devourer", for worms that thrive by excavating the bones of fallen whale carcasses.

The worms contain bacteria that help them digest the fats and oils of the whale skeletons. This type of symbiotic relationship has never been seen before, and may represent a completely new type of metabolism.

Researchers from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in Moss Landing, California, discovered a whale skeleton that was "carpeted with worms" while searching for clam beds in the trough of Monterey Canyon, some 3,000 metres deep.

But the worms were like nothing they had ever seen before. The females - roughly the thickness of a pencil and a few centimetres in length - lack eyes, mouths or stomachs. Instead they consist of a balloon-like egg sac, which branches into a greenish root system.

These branching roots grow into the whalebone to extract fats and oils from the marrow. Symbiotic bacteria that live inside the roots break down the lipids, but how nutrients are transferred from the bones to the bacteria and then to the worms is not yet known.

Radical metabolism

Scientists have been studying "whale falls" - areas where fallen whalebones have concentrated along the migratory paths of whales - for the past 15 years. But until now, all the organisms found at whale falls have used 'chemotrophic' bacteria to help them capture energy from the sulphide-rich swamps that build up around whalebones. This is the same type of metabolism used by species found at hydrothermal vents. These animals use bacteria to gain nutrition from the sulphide- and methane-enriched waters resulting from volcanic activity at the sea floor.

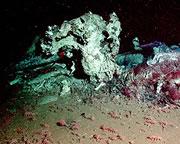

The researchers found a whale skeleton encrusted with strange pink worms.© MBARI

The researchers found a whale skeleton encrusted with strange pink worms.© MBARIThe new worms are the first animals known to exploit bacteria that break down lipids - akin to the bacteria found in oil seeps.

"It is one of the most novel uses of bacteria by invertebrates that we've seen to date," says Shana Goffredi, a marine biologist from MBARI, one of the researchers who reports the find in Science this week1. "It has driven the evolution of this animal. The worm has modified its body in order to accommodate the symbionts," she says.

Distant relative

“The worm has modified its body in order to accommodate the symbionts”

Shana Goffredi

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Scientists were at a loss to identify the worms based on their strange anatomy, but analysis of their DNA has revealed that the worms are distant relatives of the giant tubeworms that characterize hydrothermal-vent communities. The researchers determined that the two new species diverged about 42 million years ago, which is about the same time that many whale species first arose.

"The implication is that these worms were doing this job on other whale bones quite some time ago," says Bob Vrijenhoek, an evolutionary biologist from MBARI who is one of the authors on the paper. "This is not some recent invention."

Sperm factories

There were more surprises to come. The researchers have also found that whereas female worms are several inches in length, males are little more than microscopic threads, which seem to act as nothing more than sperm factories. A female worm can sweep up to 100 males at once into her egg sac, where fertilization occurs.

The researchers speculate that the sex a larva develops into is determined when it first lands on a surface, after floating around in the water. If the larva encounters a clear patch of whalebone, it becomes a female. But if there is no place for the larva to land except on another female, it does the next best thing and becomes a male, to provide that female with sperm.

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute