Abstract

The Pacific North American (PNA) teleconnection has a strong influence on North American climate. Instrumental records and century-scale reconstructions indicate an accelerating tendency towards the positive PNA state since the mid-1850s, but much less is known about long-term PNA variability. Here we reconstruct PNA-like climate variability during the mid- and late Holocene using paired oxygen isotope records from two regions in North America with robust, anticorrelated isotopic response to the modern PNA. We identify mean states of more negative and positive PNA-like climate during the mid- and late Holocene, respectively. Superimposed on the secular change between states is a robust, quasi-200-year oscillation, which we associate with the de Vries solar cycle. These findings suggest the persistence of PNA-like climate variability throughout the mid- and late Holocene, provide evidence for modulation of PNA over multiple timescales and may help researchers de-convolve PNA pattern variation from other factors reflected in palaeorecords.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large-scale teleconnections have a significant influence on regional weather and climate1. At mid-latitudes in the North Pacific and North American sectors, the Pacific North American (PNA) pattern, which exhibits strong interannual variability and interacts with other climate oscillations and forcings to produce multidecadal2,3 variability, represents the most prominent mode of atmospheric oscillation. The PNA is represented as a standardized index derived from North Pacific and North American mid-tropospheric geopotential height anomalies1, with positive PNA (PNA+) conditions associated with enhanced ridge and trough structure and meridional flows over North America and negative PNA (PNA−) with more uniform pressure fields and stronger zonal flows. Similar spatial signatures of pressure and precipitation fields associated with interdecadal or century-scale variability may be described as PNA-like inasmuch as they reflect common, coordinated changes in the atmospheric circulation, but may arise from distinct dynamical mechanisms. PNA is associated with variation in the direction and strength of the prevailing circulation and storm tracks, affecting moisture sources, temperature, precipitation amounts and isotopic composition (δ2H and δ18O), mountain snowpack and lake levels across North America2,4,5,6. The PNA is most strongly expressed in winter, but can affect climate throughout the year (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

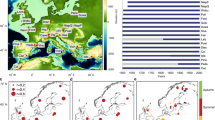

Maps show long-term (1950–2005) correlations between IsoGSM precipitation δ18O and PNA index (Climate Prediction Center) in the North American (NA) continent. (a) Cool season (December–March) correlation. (b) Annual correlation. The areas enclosed by the grey line show significance at the P<0.1 level. Both cool season and annual correlations display a northwest (NW)–southeast (SE) dipolar pattern across the NA continent, with positive correlation in the NW and negative correlation in the SE. Numbers indicate locations mentioned in the text: 1—BCC speleothem14, 2—OCNM speleothem15, 3—Lake Grinnell16, 4—Lake Jellybean10, 5—Crawford Lake29, 6—Castor Lake25, 7—Little Salt Spring24, 8—Estancia Lake23, 9—Crevice Lake26, 10—Dog Lake27, 11—Felker Lake28.

PNA-like variability is driven by internal atmospheric dynamics and external forcing. Instrumental records extending back several decades show an accelerating trend towards PNA+ conditions and a strong modulation of PNA by sea surface temperature (SST) variability7,8 associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Pacific Decadal Oscillation and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Palaeoclimate studies have adopted PNA as a framework for interpretation of century-scale climate variability in North America, documenting a secular trend towards PNA+ conditions since 1850 and periodic PNA oscillations linked to solar forcing and regional drought2,9,10,11,12,13. Although this work has greatly improved our understanding of the nature of PNA-like climate variability and associated dynamics over annual to multidecadal timescales, long-term variability of the PNA pattern and its relation to external forcing remain poorly known.

Here we assess multi-millennial reconstructions demonstrating PNA-like climate variation over a range of timescales. These reconstructions are based on recently documented anti-phase variation in precipitation water isotope ratios in western and eastern North America that is robustly and uniquely associated with variation in PNA-associated circulation patterns4,5,6 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). We compare well-dated, independent palaeoisotope proxy records situated within the western (Oregon Caves National Monument (OCNM) speleothem14 and Lake Jellybean sediment10; sites 2 and 4 in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) and eastern (Buckeye Creek Cave (BCC) speleothem15 and Lake Grinnell sediment16; sites 1 and 3) regions of isotope/PNA correlation. Each time series consists of carbonate δ18O measurements that were re-sampled to a common sampling resolution (47 years for speleothems, 35 years for lake sediments, see Methods) and represents local variation in mid-Holocene (MH) to late-Holocene (LH) precipitation δ18O values, likely overprinted by variation in local temperature, humidity and soil or lake water balance. Our results demonstrate anti-phase variability in the eastern and western regions, consistent with the expected expression of variation in the PNA pattern, over both millennial and centennial timescales. These results, supported by analysis of isotope-enabled general circulation model output and independent palaeo-precipitation proxy data, suggest that the PNA pattern may be a persistent pattern of climate system variability that has been modulated by other forcings and feedbacks over timescales of hundreds to thousands of years.

Results

Millennial-scale trends

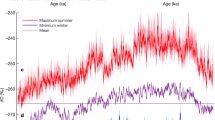

Each record (Fig. 2) exhibits substantial isotopic variability through the MH and LH (ranges of values are 1.33‰ at OCNM and 0.90‰ at BCC for speleothem carbonate, and 1.84‰ at Lake Jellybean and 1.66‰ at Lake Grinnell for lake sediment carbonate). Paired values from the re-sampled time series are significantly anticorrelated for each archive (r=−0.55, P<0.001 and neff=25 for speleothem and r=−0.13, P<0.1 and neff=11 for lake sediment, see Methods). Within each region, δ18O values of different archives also exhibit statistically significant but positive correlations (r=0.18, P<0.005 and neff=15 for the western records, re-sampled at a common 22-year resolution, and r=0.72, P<0.001 and neff=34 for the east at a 47-year resolution). Data from both lake sediments and speleothems show significant (P<0.0001) secular change throughout the period of record, with opposing trends for records derived from the western (increasing with time) and eastern (decreasing with time) sites (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). A two-sample t-test shows that the long-term mean values for the MH and LH intervals in each record are significantly different (P<0.01, see Methods). The anticorrelated change in oxygen isotope ratios in these two regions is consistent with expectations for a shift from a climate state dominated by more PNA−-like circulation conditions during the MH to more PNA+-like conditions during the LH4,5,6.

(a) OCNM speleothem δ18O. (b) BCC speleothem δ18O. (c) Lake Jellybean sediment δ18O. (d) Lake Grinnell δ18O. Red and blue lines denote the records from western and eastern North America, respectively. The dashed lines show the mean values of each record for the MH and LH (for the demarcation of the MH and LH, see Supplementary Fig. 2).

Variation in the individual δ18O records has previously been attributed to effects of changing local temperature, precipitation, moisture sources and storm tracks driven by large-scale climate modes10,14,15,16. The significant anticorrelated variation identified here for the western and eastern regions suggests that these records are responding to a common, large-scale climatic teleconnection between the regions. We suggest that the inversely correlated component of isotopic change in the western and eastern sites may reflect long-term variability of the mean state of PNA through the Holocene based on the documented association of anti-phase precipitation isotopic variation in these regions with PNA. During the MH, relatively low δ18O values in the west coupled with relatively high δ18O values in the east are consistent with dominance of a more PNA−-like climate pattern over North America (Fig. 2), supporting enhanced zonal circulation10. By contrast, LH isotope records suggest a PNA+-like mean state, characterized by enhanced meridional circulation17,18 with higher δ18O values in western North America and lower values in the east. The shift between these states is nearly synchronous with climatic and hydrological changes recorded in a number of different proxies across North America19,20,21, and corresponds temporally with the 4.2–3.9 kyr before present (BP) abrupt climate event documented globally22.

Our result is supported by independent proxy evidence from a range of sites across the continent. Published MH records suggest drier conditions in the southwestern United States23 (site 8 in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) and Florida24 (site 7). For the same time interval, wetter conditions are reconstructed in the Pacific Northwest (NW)25 (site 6), southwestern Montana26 (site 9) and British Columbia27,28 (sites 10 and 11), and wetter conditions and 18O-depleted precipitation have been inferred in the Great Lakes region29 (site 5). This distribution is generally consistent with the pattern of precipitation change associated with the modern PNA− state (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 1b), which features enhanced precipitation across the Pacific NW, Northern Rocky Mountains and upper Midwestern United States, and reduced precipitation in the southwestern and southeastern United States and across the central and southern Great Plains. It is also consistent with expectations30,31 for circulation patterns associated with independently documented negative Pacific Decadal Oscillation and/or La Niña-like patterns in the Pacific18,32 and a positive North Atlantic Oscillation pattern32,33 during the MH.

Results are from IsoGSM and show cool season (December–March) differences. (a) Precipitation δ18O (‰, VSMOW) difference between late Holocene (LH) and mid Holocene (MH; LH minus MH). (b) Precipitation (mm day−1) and vertically integrated moisture flux (kg m−1 s−1) field difference between LH and MH. (c) Precipitation δ18O (‰, VSMOW) difference between PNA+ and PNA−. (d) Precipitation (mm day−1) and vertically integrated moisture flux (kg m−1 s−1) field difference between PNA+ and PNA−. LH simulations are based on a 20-year integration forced with modern SSTs and greenhouse gases and the MH simulation is a 20-year integration using orbital configuration at 6,000 year BP and MH SST forcing (see Methods for the details). The areas enclosed by the grey lines show significant (P<0.1) precipitation and isotope differences. The arrows in b and d denote vertically integrated moisture flux (kg m−1 s−1).

General circulation modelling

Results from the proxy data are further supported by climate model output from the Isotopes-incorporated Global Spectral Model (IsoGSM34) and the Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project Phase III archive. We evaluated IsoGSM simulations forced with MH and LH boundary conditions (see Methods), which show a spatially coherent pattern of winter precipitation δ18O change across the North American continent (Fig. 3a). LH conditions feature higher δ18O values in the NW and slightly lower values in the southeast (Fig. 3a). Similar patterns of isotope change also exist if this comparison is conducted for annual average values, but with weaker spatial coherence (Supplementary Fig. 3). The IsoGSM results are roughly consistent with results from other isotope-enabled atmospheric (LMDZ-iso35; Supplementary Fig. 4) and coupled ocean-atmosphere (ModelE36) models. Comparison of the IsoGSM results with simulations from non-isotope-enabled models included in the Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project Phase III shows broad congruence in patterns of precipitation change between the MH and LH (Supplementary Fig. 5). Drier conditions dominate across southeastern North America in all models and half of models simulate slightly wetter conditions in the NW (HadGEM2-CC, IsoGSM, MIROC-ESM, MPI-ESM-P and MRI-CGCM3) during the MH, further supporting the robustness of the hydrological changes simulated by IsoGSM.

The isotope changes simulated in IsoGSM are associated with enhanced southwesterly moisture flux (delivering vapour more enriched in 18O) to NW North America and northerly to easterly moisture flux (more depleted in 18O) to southeast North America during the LH compared with MH (Fig. 3b). Despite differences in magnitude, the spatial structure of modelled isotope and climate field differences between LH and MH is similar to that between the PNA+ and PNA− states (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 6), supporting our interpretation that MH to LH shifts in the proxy records may reflect a change in the mean state of the PNA pattern. Changes in pressure fields between the two modelled Holocene states are similar to those associated with modern PNA, characterized by positive surface pressure anomalies that arc from the Hawaiian Islands over the western interior of North America and negative surface pressure anomalies over the southeastern United States and/or Aleutian Islands during LH (Supplementary Fig. 7, except GISS-E2-R). Modelled LH conditions are also characterized by a more negative NAO-like pattern in north Atlantic pressure (Supplementary Fig. 7, except CCSM4, HadGEM2-CC and MRI-CGCM3), and a more El Niño-like pattern in the tropical Pacific SSTs (relative to modelled MH conditions; Supplementary Fig. 8, except GISS-E2-R and HadGEM2-CC), consistent with previous palaeoclimate reconstruction18,33 and modelling37,38.

Centennial-scale variability

The oxygen isotope proxy records also exhibit substantial short-term (centennial) variation superimposed on the millennial-scale trends. Cross-spectral analysis for paired speleothem or sediment δ18O records from the two regions indicates coherent, statistically significant (>90% confidence) variability at periodicities of 195 years for speleothems and 219 years for lake sediments (Fig. 4a,b). Although similar coherent periodicities can also be identified in cross-comparisons of the records from the two regions (that is, speleothem versus lake sediment) these are not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 9), perhaps due in part to differences in time averaging and/or resolution of the different archives. Band-pass-filtered δ18O records targeting these frequencies show robust (r=−0.96, P<0.0001 for speleothem and r=−0.95, P<0.0001 for lake sediment) anti-phase oscillations, consistent with expected response to PNA pattern variation (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. 10). Filtered records from all sites exhibit similar patterns of amplitude modulation throughout the period of record. Although the period of these variations approaches the limits of uncertainty associated with the proxy record age models, the common signal in all four records, in terms of both frequency and amplitude, suggests that they are responding to common, large-scale forcing. Furthermore, age model errors could only explain the anti-phase, PNA-like oscillations recorded by both proxy pairs in the event that there were systematic biases producing a common phase-shift in both lacustrine and speleothem records, an unlikely occurrence. Comparison of the δ18O records from the eastern sites with an independently reconstructed, 1,000-year PNA index12 reveals strong coherence of phase and amplitude variations within the ~200-year periodicity domain (inset panels in Fig. 4c,d), further supporting the identification and extrapolation of PNA variability in this frequency domain throughout the MH and LH.

(a,b) Power and coherency spectra for (a) OCNM (red) and BCC (blue) Speleothem δ18O records and (b) Lake Jellybean (red) and Lake Grinnell (blue) sediment δ18O records. The cross-spectral analysis was performed using computer package SPECTRUM48 (see Methods). Periods of the main spectral peaks are labelled. The horizontal dashed lines indicate significance at the 90 and 95% level in the coherence spectra. Grey bars denote significantly strong coherence between paired proxy δ18O records. (c) Paired speleothem δ18O time series after 195±5 year band-pass filtering. (d) Paired lake sediment δ18O time series after 219±5 year band-pass filtering. Insets in c and d are the comparisons of BCC speleothem and Lake Grinnell δ18O records with independently reconstructed PNA index values12 (pink line) filtered in the 200±5 year periodicity domain. Note that the δ18O records are inverted to express their anticorrelation with the PNA index. All filtering used a third-order Butterworth band-pass filter.

Discussion

Our results identify similar, spatially structured changes in North American hydroclimate occurring on two different timescales during the Holocene. The pattern of change in isotopic records, climate model simulations and independent proxy data are similar to that associated with modern PNA, suggesting that these records may reflect a common pattern of atmospheric variability reminiscent of, or involving, a change in the mean state of PNA. If so, PNA may represent a persistent pattern of climate system variability throughout the MH to LH, which was modulated by changes in forcing and/or interaction with other dynamical modes over a range of timescales.

The transition between the MH and LH is characterized by a substantial change in insolation that affected many parts of the climate system32. PNA-like changes in North American climate at this time may reflect the influence of orbitally driven meridional migration of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) and ENSO. The MH to LH decrease in summer/annual insolation has been associated with a southward shift of the ITCZ39. Southward displacement of the ITCZ induces a PNA-like extratropical atmospheric response40, with a barotropic ridge over the Rocky Mountains accompanied by a deepened trough (a southward shift of the polar jet) in southeastern North America in winter. This would lead to drier conditions in northwestern North America and wetter conditions in the southeastern United States during the LH (Supplementary Fig. 5). This PNA-like response is further amplified by a warm LH eastern tropical Pacific SST (as during El Niño; Supplementary Fig. 8) that can produce enhanced Rossby wave propagation from the tropical Pacific, directly exciting the PNA pattern41.

Centennial-scale North American climate variability during the Holocene has previously been linked to variations in solar radiation42. The 195- and 219-year periodicities identified and associated with modulation of palaeo-PNA variability here are similar to that of the 210-year de Vries (Suess) solar cycle43, which may suggest a persistent link between PNA-associated North American climate changes and solar variability during the MH and LH. Previous studies have demonstrated that variation in solar ultraviolet radiation can lead to shifts in regional atmospheric circulation patterns and the polar jet through heating and ozone chemistry in the middle atmosphere44. North American circulation patterns for low and high solar activity winters during the period of instrumental record show strong associations with PNA+ and PNA− circulation patterns, respectively45 (Supplementary Fig. 11). A recent 275-year PNA reconstruction further supports this association, with two prominent solar minima (Dalton and Damon) being characterized by strong PNA+ conditions2.

Hydroclimatic variability in continental North America is closely linked to the large-scale circulation, and a large number of studies have previously related regional palaeoclimatic change to storm tracks and moisture transport10,11,12,13,14,15,17,25,29. Our work suggests strong, continental-scale coherency in these changes at centennial to millennial scales throughout the past 8,000 years. The association of MH to LH isotopic and climatic variability with PNA-like shifts in atmospheric circulation suggests that the PNA pattern was a persistent feature of the North American climate. Given demonstrated links between other major climatic modes and the PNA pattern, modulation of PNA variation offers a unifying and consistent framework for translating large-scale climate system trends (for example, MH to LH shifts in ENSO18,32) and variability (for example, in response to solar cycles43,44) into regionally coherent climatic change across North America. This framework could be further tested as transient climate model simulations spanning this period of Earth history become available. The proposed associations may provide an indication of the spatial structure of future continental hydroclimatic impacts expected under shifting climatic regimes (for example, Fig. 3). In addition, our work indicates systematic, regional variation in moisture sources and precipitation δ18O values throughout the MH to LH, and recognition of these patterns will be important for de-convolving these large-scale changes from variation in other regional or local climatic variables reflected in palaeoclimate proxy archives.

Methods

Selection of palaeoclimate proxy records

Two pairs of palaeoclimate proxy records were selected for analysis, including speleothem records from West Virginia (BCC) and Oregon (OCNM) and lake sediment records from New Jersey (Lake Grinnell) and Yukon (Lake Jellybean). With the exception of Lake Grinnell, the records were retrieved from the NOAA World Data Center for Paleoclimatology ( http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/data.html). The records were chosen based on two primary selection criteria: proximity of the study site relative to the two poles of correlation between modern isotopes in precipitation and PNA index, and high temporal resolution (average sampling interval of 50 years or better) throughout the MH and LH.

Age model and re-sampling of time series data

Age models for all sites are derived from the original data source and are fully described in the primary references. The BBC age model was based on linear interpolation between U/Th ages for each speleothem. Average analytical uncertainty (2σ) for the individual age determinations was 49 years15. The OCNM speleothem age model was derived from 29 high-precision U/Th dates using Markov Chain Monte–Carlo sampling and Bayesian statistics14. The average uncertainty (2σ) for the individual age determinations through the period of record used here was 140 years. The Lake Grinnell sediment core was dated using seven accelerator mass spectrometry 14C determinations on terrestrial plant macrofossils, with an average uncertainty (2σ, calibrated age) throughout the period of record used here of 49 years16. Ages were assigned using a fourth-order polynomial curve fit to these data, with a fixed surface age (−55 cal year BP=2005 AD). The chronology of the Lake Jellybean sediment core was determined based primarily on seven accelerator mass spectrometry 14C measurements of terrestrial macrofossils and pollen, supported by 210Pb and 137Cs data from shallow sediments and identification of an independently dated ash layer10. Uncertainty (1σ) in the calibrated radiocarbon ages varies from 80 to 157 years (average=120 years). All ages discussed in this paper are reported using calendar years BP, where present is defined as 1950 AD. Ages post-dating 1950 are reported as negative.

For speleothem records, BCC is derived from records from three speleothems: BCC2, BCC4 and BCC6, with an average time resolution of 35, 46 and 47 years, respectively. The three raw BBC speleothem chronologies were combined to yield a composite representative of the underlying climate variability. To this end, each speleothem record was re-sampled at common, 47-year intervals, using linear interpolation between data points. A composite time series was calculated by averaging values from the three interpolated BCC time series. OCNM has an average time resolution of 3 years, but to facilitate analysis this record was also re-sampled at the same time points (47-year interval) as BCC by linear interpolation between adjacent data points. For lake sediment records, the Lake Grinnell and Lake Jellybean records have an average resolution of 35 and 22 years, respectively. Both records were re-sampled at a common 35-year interval by linear interpolation.

For all time series data δ(t), the linear interpolation procedure estimated δ-values for an element t of an evenly spaced time vector based on the two neighbouring measurements δ(ti) and δ(tj):  where ti≤t≤tj. All interpolation was conducted in Matlab R2012b.

where ti≤t≤tj. All interpolation was conducted in Matlab R2012b.

Statistical analysis

To determine the correlation of paired proxy records, the Pearson coefficient rxy of two time series was calculated as  , where n is the sample size,

, where n is the sample size,  and

and  are the sample means, and Sx and Sy are the sample s.d. To account for autocorrelation within individual time series, we computed the ‘effective’ sample size46:

are the sample means, and Sx and Sy are the sample s.d. To account for autocorrelation within individual time series, we computed the ‘effective’ sample size46:  , where rxl and ryl are the autocorrelation at lag l for paired time series. The Student’s t-value for assessing significance was calculated as

, where rxl and ryl are the autocorrelation at lag l for paired time series. The Student’s t-value for assessing significance was calculated as  .

.

The difference between MH and LH δ18O values for each record was evaluated using the two-sample t-test47 with a correction to calculate effective sample numbers accounting for autocorrelation in each record (neff=n(1−ρ)/(1+ρ), where n is the number observations in a record before correction and ρ is the lag 1 autocorrelation in the time series). Mean values were found to be different with P<<0.01 for all records. The OCNM record has mean δ18O values of −8.78±0.18‰ and −9.11±0.23‰ for LH and MH, respectively (T=4.19, neff,1=14, neff,2=14, dfeff=26). The BCC record has mean values of −6.10±0.08‰ and −5.81±0.09‰ for LH and MH, respectively (T=−4.52, neff,1=4, neff,3=3, dfeff=5). The Lake Jellybean record has mean values of −19.44±0.36‰ and −19.67±0.26‰ for LH and MH, respectively (T=2.52, neff,1=25, neff,2=24, dfeff=47). The Lake Grinnell record has mean values of −7.93±0.20‰ and −7.39±0.25‰ for LH and MH, respectively (T=−4.81, neff,1=8, neff,2=9, dfeff=15).

Time series analysis

Cross-spectral analysis of each paired δ18O time series was performed using the computer package SPECTRUM48. We used a Welch-type spectral window, with a number of overlapping (50%) segments (nseg) of 5. Considering the 47- (for speleothem) and 35-year (for lake sediment) resolution of our records, we disregard spectral peaks below the Nyquist period of 100 years (0.01 year−1).

Climate model simulations

IsoGSM34 was run with a horizontal resolution of T62 (about 180 km) and 28 vertical layer to generate the simulations used in this study. We have run three separate sets of simulations. First, for the historical run, that is, 1871–2009, IsoGSM was nudged towards NOAA-20C re-analysis atmospheric data49 (wind speed, surface temperature and surface pressure) with a spectral nudging technique for large scale (larger than 1,000 km) waves34. Second, a LH (present day) simulation was conducted where monthly climatologies of SST and sea-ice distribution for the period 1979–2007 obtained from the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP) were averaged and used to force the IsoGSM atmosphere. Third, the MH (6 kyr BP) IsoGSM run was performed similar to the LH simulation, but with changes to the surface forcing, orbital parameters and greenhouse gas concentrations. The MH IsoGSM simulation was forced with monthly mean SSTs and sea ice fractions from a 400-year Institute Pierre Simon Laplace atmosphere ocean general circulation model simulation of the MH50. We first calculated the SST and sea-ice difference between the MH and pre-industrial simulations by the Institute Pierre Simon Laplace model. Then we added these differences to the SST and sea ice observed for the present-day conditions, as detailed in Risi et al.35 For the MH IsoGSM simulation, the solar orbital parameters were adjusted (eccentricity=0.018682, precession =0.87 and obliquity=24.105) and the greenhouse gas concentrations were lowered ([CO2]=280 p.p.m., [CH4]=650 p.p.b. [N2O]=200 p.p.b., [CFC-11]=0 p.p.t. and [CFC-12]=0 p.p.t.). Both LH and MH simulations were run with a 100-s time step, and neither simulation was spectrally nudged. Both IsoGSM simulations were run for 30 years and the last 20 years were used for analyses.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Liu, Z. et al. Paired oxygen isotope records reveal modern North American atmospheric dynamics during the Holocene. Nat. Commun. 5:3701 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4701 (2014).

References

Wallace, J. M. & Gutzler, D. S. Teleconnections in the geopotential height field during the Northern Hemisphere winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 109, 784–812 (1981).

Trouet, V. & Taylor, A. H. Multi-century variability in the Pacific North American circulation pattern reconstructed from tree rings. Clim. Dyn. 35, 953–963 (2010).

Overland, J. E., Adams, J. M. & Bond, N. A. Decadal variability of the aleutian low and its relation to high-latitude circulation*. J. Clim. 12, 1542–1548 (1999).

Liu, Z., Kennedy, C. D. & Bowen, G. J. Pacific/North American teleconnection controls on precipitation isotope ratios across the contiguous United States. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 310, 319–326 (2011).

Liu, Z., Bowen, G. J., Welker, J. M. & Yoshimura, K. Winter precipitation isotope slopes of the contiguous USA and their relationship to the Pacific/North American (PNA) pattern. Clim. Dyn. 41, 403–420 (2012).

Liu, Z., Yoshmura, K., Bowen, G. J. & Welker, J. M. Pacific North American teleconnection controls on precipitation isotopes (δ18O) across the contiguous United States and adjacent regions: a GCM-based analysis. J. Clim. 27, 1046–1061 (2014).

Horel, J. D. & Wallace, J. M. Planetary-scale atmospheric phenomena associated with the southern oscillation. Mon. Weather Rev. 109, 813–829 (1981).

Yu, B., Shabbar, A. & Zwiers, F. W. The enhanced PNA-like climate response to Pacific interannual and decadal variability. J. Clim. 20, 5285–5300 (2007).

Moore, G., Holdsworth, G. & Alverson, K. Climate change in the North Pacific region over the past three centuries. Nature 420, 401–403 (2002).

Anderson, L., Abbott, M. B., Finney, B. P. & Burns, S. J. Regional atmospheric circulation change in the North Pacific during the Holocene inferred from lacustrine carbonate oxygen isotopes, Yukon Territory, Canada. Quat. Res. 64, 21–35 (2005).

Edwards, T. W. D., Birks, S. J., Luckman, B. H. & MacDonald, G. M. Climatic and hydrologic variability during the past millennium in the eastern Rocky Mountains and northern Great Plains of western Canada. Quat. Res. 70, 188–197 (2008).

Hubeny, J. B., King, J. W. & Reddin, M. Northeast US precipitation variability and North American climate teleconnections interpreted from late Holocene varved sediments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17895–17900 (2011).

Kirby, M. E., Mullins, H. T., Patterson, W. P. & Burnett, A. W. Late glacial–Holocene atmospheric circulation and precipitation in the northeast United States inferred from modern calibrated stable oxygen and carbon isotopes. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 114, 1326–1340 (2002).

Ersek, V., Clark, P. U., Mix, A. C., Cheng, H. & Edwards, R. L. Holocene winter climate variability in mid-latitude western North America. Nat. Commun. 3, 1219 (2012).

Hardt, B., Rowe, H. D., Springer, G. S., Cheng, H. & Edwards, R. L. The seasonality of east central North American precipitation based on three coeval Holocene speleothems from southern West Virginia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 295, 342–348 (2010).

Zhao, C., Yu, Z., Ito, E. & Zhao, Y. Holocene climate trend, variability, and shift documented by lacustrine stable-isotope record in the northeastern United States. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1831–1843 (2010).

Fisher, D. et al. The Mt Logan Holocene—late Wisconsinan isotope record: tropical Pacific—Yukon connections. Holocene 18, 667–677 (2008).

Barron, J. A. & Anderson, L. Enhanced Late Holocene ENSO/PDO expression along the margins of the eastern North Pacific. Quatern. Int. 235, 3–12 (2011).

Zhang, Q. B. & Hebda, R. J. Abrupt climate change and variability in the past four millennia of the southern Vancouver Island, Canada. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L16708 (2005).

Li, Y.-X., Yu, Z. & Kodama, K. P. Sensitive moisture response to Holocene millennial-scale climate variations in the Mid-Atlantic region, USA. Holocene 17, 3–8 (2007).

Salzer, M. W., Bunn, A. G., Graham, N. E. & Hughes, M. K. Five millennia of paleotemperature from tree-rings in the Great Basin, USA. Clim. Dyn. 42, 1517–1526 (2013).

Booth, R. K. et al. A severe centennial-scale drought in midcontinental North America 4200 years ago and apparent global linkages. Holocene 15, 321–328 (2005).

Menking, K. M. & Anderson, R. Y. Contributions of La Niña and El Niño to middle Holocene drought and late Holocene moisture in the American Southwest. Geology 31, 937–940 (2003).

Alvarez Zarikian, C. A., Swart, P. K., Gifford, J. A. & Blackwelder, P. L. Holocene paleohydrology of Little Salt Spring, Florida, based on ostracod assemblages and stable isotopes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 225, 134–156 (2005).

Nelson, D. B. et al. Drought variability in the Pacific Northwest from a 6,000-yr lake sediment record. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 3870–3875 (2011).

Whitlock, C. et al. Holocene seasonal variability inferred from multiple proxy records from Crevice Lake, Yellowstone National Park, USA. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 331, 90–103 (2012).

Hallett, D. J. & Hills, L. V. Holocene vegetation dynamics, fire history, lake level and climate change in the Kootenay Valley, southeastern British Columbia, Canada. J. Paleolimnol. 35, 351–371 (2006).

Galloway, J. M., Lenny, A. M. & Cumming, B. F. Hydrological change in the central interior of British Columbia, Canada: diatom and pollen evidence of millennial-to-centennial scale change over the Holocene. J. Paleolimnol. 45, 183–197 (2011).

Yu, Z., McAndrews, J. H. & Eicher, U. Middle Holocene dry climate caused by change in atmospheric circulation patterns: evidence from lake levels and stable isotopes. Geology 25, 251–254 (1997).

Yu, B. & Zwiers, F. The impact of combined ENSO and PDO on the PNA climate: a 1,000-year climate modeling study. Clim. Dyn. 29, 837–851 (2007).

Honda, M., Nakamura, H., Ukita, J., Kousaka, I. & Takeuchi, K. Interannual seesaw between the Aleutian and Icelandic lows. Part I: Seasonal dependence and life cycle. J. Clim. 14, 1029–1042 (2001).

Wanner, H. et al. Mid-to late Holocene climate change: an overview. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 1791–1828 (2008).

Rimbu, N., Lohmann, G., Kim, J.-H., Arz, H. & Schneider, R. Arctic/North Atlantic oscillation signature in Holocene sea surface temperature trends as obtained from alkenone data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1280 (2003).

Yoshimura, K., Kanamitsu, M., Noone, D. & Oki, T. Historical isotope simulation using reanalysis atmospheric data. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D19108 (2008).

Risi, C., Bony, S., Vimeux, F. & Jouzel, J. Water-stable isotopes in the LMDZ4 general circulation model: Model evaluation for present-day and past climates and applications to climatic interpretations of tropical isotopic records. J. Geophys. Res. 115, D12118 (2010).

Schmidt, G. A., LeGrande, A. N. & Hoffmann, G. Water isotope expressions of intrinsic and forced variability in a coupled ocean-atmosphere model. J. Geophys. Res. 112, D10103 (2007).

Dietrich, S., Werner, M., Spangehl, T. & Lohmann, G. Influence of orbital forcing and solar activity on water isotopes in precipitation during the mid-and late Holocene. Clim. Past 9, 13–26 (2013).

Rimbu, N., Lohmann, G., Lorenz, S., Kim, J.-H. & Schneider, R. Holocene climate variability as derived from alkenone sea surface temperature and coupled ocean-atmosphere model experiments. Clim. Dyn. 23, 215–227 (2004).

Haug, G. H., Hughen, K. A., Sigman, D. M., Peterson, L. C. & Röhl, U. Southward migration of the intertropical convergence zone through the Holocene. Science 293, 1304–1308 (2001).

Kwon, Y.-O., Deser, C. & Cassou, C. Coupled atmosphere–mixed layer ocean response to ocean heat flux convergence along the Kuroshio Current extension. Clim. Dyn. 36, 2295–2312 (2011).

Horel, J. D. & Wallace, J. M. Planetary-scale atmospheric phenomena associated with the Southern Oscillation. Mon. Weath. Rev. 109, 813–829 (1981).

Yu, Z. C. & Ito, E. Possible solar forcing of century-scale drought frequency in the northern Great Plains. Geology 27, 263–266 (1999).

Braun, H. et al. Possible solar origin of the 1,470-year glacial climate cycle demonstrated in a coupled model. Nature 438, 208–211 (2005).

Gray, L. J. et al. Solar influences on climate. Rev. Geophys. 48, RG4001 (2010).

Liu, Z., Yoshimura, K., Buenning, N. H. & He, X. Solar cycle modulation of the Pacific–North American teleconnection influence on North American winter climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 024004 (2014).

Box, G. E., Jenkins, G. M. & Reinsel, G. C. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River (1994).

Snedecor, G. W. & Cochran, W. G. Statistical Methods 8th edn Iowa State Univ. Press (1989).

Schulz, M. & Stattegger, K. SPECTRUM: spectral analysis of unevenly spaced paleoclimatic time series. Comput. Geosci. 23, 929–945 (1997).

Compo, G. P. et al. The twentieth century reanalysis project. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 137, 1–28 (2011).

Marzin, C. & Braconnot, P. Variations of Indian and African monsoons induced by insolation changes at 6 and 9.5 kyr BP. Clim. Dyn. 33, 215–231 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Zhao, J. Bradford Hubeny, Z. Lundeen and M. Werner for providing access to palaeoclimate proxy data and modelled isotope data. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (41171022) and a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowship and to Z.F.L. Additional support was provided by the MEXT SOUSEI program to K.Y. and US National Science Foundation Grants EF-01241286 to G.J.B. and EAR-0902895 to F.S.Y.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.F.L. and G.J.B. conceived the study. Z.F.L., K.Y. and G.J.B. analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. K.Y., N.H.B. and C.R. ran the model experiments. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-11 (PDF 2474 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Yoshimura, K., Bowen, G. et al. Paired oxygen isotope records reveal modern North American atmospheric dynamics during the Holocene. Nat Commun 5, 3701 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4701

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4701

This article is cited by

-

Climate and the latitudinal limits of subtropical reef development

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Evaluating hydrological influences on mid-latitude δ18Op in the Middle East

Climate Dynamics (2018)

-

A 2700-year record of ENSO and PDO variability from the Californian margin based on coccolithophore assemblages and calcification

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2017)

-

The response of winter Pacific North American pattern to strong volcanic eruptions

Climate Dynamics (2017)

-

Arctic Vortex changes alter the sources and isotopic values of precipitation in northeastern US

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.