Abstract

Coherence in light–matter interaction is a necessary ingredient if light is used to control the quantum state of a material system. Coherent effects are firmly associated with isolated systems kept at low temperature. The exceedingly fast dephasing in condensed matter environments, in particular at elevated temperatures, may well erase all coherent information in the material at timescales shorter than a laser excitation pulse. Here we show for an ensemble of semiconductor quantum dots that even in the presence of ultrafast dephasing, for suitably designed condensed matter systems quantum-coherent effects are robust enough to be observable at room temperature. Our conclusions are based on an analysis of the reshaping an ultrafast laser pulse undergoes on propagation through a semiconductor quantum dot amplifier. We show that this pulse modification contains the signature of coherent light–matter interaction and can be controlled by adjusting the population of the quantum dots via electrical injection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coherent control of the quantum state of matter by light is an established technique, in particular for isolated material systems1,2,3,4. The nature of coherent interactions allows to reversibly change the state of matter and the state of the electromagnetic field on an ultrafast timescale without energy loss. A particularly illustrative realization of such a process in a resonantly driven two-level system are Rabi oscillations, showing the complete and reversible periodic excitation of a two-level system5. The qubits of quantum computing, for example, are based on Rabi oscillations in single two-level systems. Harnessing coherent processes, the deterministic nature of which allows steering the energy flow in the coupled light–matter system, opens up new avenues for applications also in mesoscopic and macroscopic devices6,7,8,9. For a semiconductor device operating in the coherent regime based on Rabi oscillations, the comparatively slow gain recovery process via replenishing the active carriers from a reservoir10, hitherto limiting the performance of devices to data rates of about 200 Gb s−1 (refs 11, 12), could be avoided. Implementing coherent sub-picosecond, not population lifetime limited processes, for example, ultrafast switching, opens the new field of coherent photonics.

Rabi flopping has been observed in various semiconductor systems of different dimensionality at low temperature13,14, in particular in isolated centres like quantum dots (QDs)15,16,17. QDs are zero-dimensional structures formed by self-organization, and show an atom-like delta-function density of states18,19. They support localized excitations, although they are immersed in a solid-state environment. With this unique combination of single-particle behaviour and condensed matter characteristics20,21, they are ideally suited for studying the response of a complex system to excitation by a light pulse. In addition, self-assembled QDs are readily integrated into electrically pumped device structures, with the electrical injection allowing to control the initial population of their quantum states.

For QD structures, decoherence times of 50–500 fs, depending on the injection current, have been predicted and determined22,23,24, making it hard to directly observe Rabi oscillations, as scattering rapidly scrambles the phases, reducing a reversible oscillation to an irreversible equilibration. The coherent light–matter interaction, however, still does leave its traces on the electromagnetic field of the exciting pulse as it leaves the sample, opening an alternative method of measurement. The only necessary condition in this case is that the pulse induces a complete Rabi flop during the time within which the polarization in the medium is not completely damped. Since the Rabi frequency Ω scales with the field strength E, strong optical pulses are required.

Signatures of coherent light–matter interaction on the electromagnetic field at room temperature have been predicted in numerical simulations for quantum well (QW) structures25,26. Indeed, Rabi oscillations in a quantum cascade structure with two-dimensional (2D) confinement—at low temperature—have recently been observed by analysing the change in pulse shape of an intense laser pulse propagating through the material9. Also, a pulse in a quantum-dash-based device has been shown to exhibit signatures of Rabi oscillations27.

Here we show that an intense laser pulse interacting with an ensemble of QDs can drive Rabi oscillations fast enough to be observable even in a solid-state environment at room temperature. The signature of Rabi oscillations is retained even under conditions of electrical pumping, adding the QD inversion as an additional control parameter. Adjusting the QD population via the electrical current allows for switching the modulations of the pulse shape, thus controlling coherent effects through population. These effects have on one hand the potential to be exploited for ultrafast modulation of optical signals. On the other hand, for telecommunications applications it is advised to keep the light intensity at levels low enough to avoid a distortion of the bit sequence due to unwanted coherent modulation.

Results

Experimental observation of laser pulse reshaping

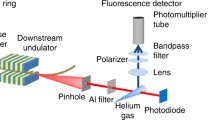

In our experiment, we observe the changes a strong Gaussian laser pulse undergoes when propagating at room temperature through an In(Ga)As-based QD-semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA). The device offers the possibility of electrical current injection. Laser pulses with a central wavelength of 1,280 nm, resonant to the QD ground-state (GS) transition, are generated in an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) pumped by a Ti:sapphire laser with a repetition rate of 75.4 MHz (Coherent MIRA 900-HP). The pulse profile is a Gaussian function with a temporal and spectral full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 230 fs and 15 nm, respectively. We analyse the pulse shape in amplitude and phase in a heterodyne cross-correlation experiment. A scheme of the set-up is shown in Fig. 1. This frequency-resolved optical short-pulse characterization by heterodyning (FROSCH) is capable of tracing the oscillations of the complex electric field convolution with a resolution better than π/20, corresponding to 0.1 fs. Being a linear method, and analysing the electric field rather than the intensity, it offers an intrinsically high sensitivity even at low signal levels. A more detailed description of the experimental procedure is given in the Methods section.

Schematic of the FROSCH set-up for electric field cross-correlation measurement of fs pulses. To illustrate the time resolution of the method, the inset shows a zoom into a representative set of data, the real (blue) and imaginary (red) part of the lock-in signal and the interference pattern of the reference diode with a wavelength of λ=780 nm (green).

The experimentally determined pulse shape modification observed on the output facet of the device for a Gaussian input pulse for different pulse powers and injection currents is displayed in Fig. 2. The experimental results are given as a convolution of the electric field of the probe pulse passing the device with a Gaussian reference pulse. The black lines in the top row and centre row represent the measured convolution in terms of amplitude and phase, respectively. An alternative visualization of the time-dependent information contained in the exciting pulse is a Gabor transformation. This transformation basically yields time-resolved power spectra, as for example, also known from wavelet theory, and is thus discussed in frequency–time space. The bottom row of Fig. 2 shows the results, with the Gabor transform of the experimental signal S(τ) defined as

Top row: electric field convolution amplitudes after propagation of the probe pulse through the device for a range of injection currents J (black: experiment, red: simulation). Middle row: convolution phases (black: experiment, red: simulation). Bottom row: absolute values of the Gabor transform of the experimental signal. (a) Low pulse intensity. (b–e) High pulse intensity with injection currents J of (b) 0J0 (absorbing regime), (c) 3J0 (transparency), (d, e) 20J0 and 30J0 (amplifying regime).

Here, c0 is the speed of light and σ=106 fs is the half width at half maximum of an elementary minimum uncertainty wavelet. In our experiment, a weak pulse passes the unpumped device without a significant change in the pulse shape (Fig. 2a). Increasing the pulse intensity leads to the appearance of interesting modifications, see Fig. 2b–d, as a result of the fact that the frequency of Rabi oscillations increases linearly with the pulse area Θ (ref. 5), that is, a dimensionless quantity for the integrated electric field intensity of the laser pulse. The signature of the QD dynamics shows up in the amplitude (top row) as a dip, accompanied by a step in the phase (centre row) and is translated into a hole in the Gabor surfaces (bottom row).

Numerical simulation based on Maxwell–Bloch equations

To substantiate the discussion, we model the signal amplification inside the QD-SOA by semiclassical Maxwell–Bloch equations28,29,30. We simulate the quantum device by a zero-dimensional two-level system (QD) coupled to a reservoir of charge carriers in a 2D reservoir (QW/wetting layer), being in non-equilibrium as a result of electrical carrier injection (see refs 10, 31, 32). The model includes 0D–2D in- and out-scattering processes as detailed in the Methods section. The results of the numerical simulations are displayed as red convolution amplitude and phase curves in Fig. 2. The calculated pulse modification is in excellent agreement with the experimental results, in particular it reproduces the coincidence of amplitude dip and phase jump consistently observed in the experiment. Further, it can be seen that our modelling is able to correctly describe the pulse modifications for all the different electrical pump currents and thus allows for a deep understanding of the underlying microscopic processes as will be detailed below.

Discussion

To make the complex system of coupled differential equation accessible to physical intuition, we first condense the essence of the dynamic expressions to a basic skeleton of a dipole coupled to a light field, which results in equations formally analogous to the well-known coupled oscillators of classical mechanics, see Methods section. The dynamics of this system is displayed in Fig. 3. We consider a light-field pendulum triggered by an excitation with a frequency ωL and a Gaussian amplitude in time, coupled resonantly to a QD pendulum (Fig. 3a). Comparing with the Maxwell–Bloch equations without propagation, the light pendulum is identified with the real part of the electric field amplitude E(t) and the QD pendulum with the real part of the polarization P(t). For a suitable choice of the coupling parameters, the oscillation energy is flowing from light pendulum to QD pendulum and back during the time permitted by the time-dependent amplitude of excitation (during the pulse). The envelopes and phases of the pendula relative to the phase of the excitation are displayed in Fig. 3b,c, respectively, so the fast oscillations (frequency ωL) are removed for clarity. The time traces of the dynamics of the light pendulum and the QD pendulum both show points in time at which the oscillation amplitude is reduced to a minimum, and a phase jump occurs. From basic mechanics, it is known that in a forced oscillation, there is a phase difference of about π/2 between the driving force and the oscillator coupled to it. Thus, the time instants at which the oscillation stops and the phase rapidly changes can be qualitatively understood as the instants at which the role of the respective pendulum changes from driving the oscillation to being driven by the partner pendulum. In a convolution of light pendulum oscillations with excitation oscillations, corresponding to the convolution of the electric fields of probe pulse Ep(t) and reference pulse Er(t) in our experiment, the signature of switching in the dynamics of the light pendulum is retained (Fig. 3d). Also, the analogue Gabor surface of our mechanical model displays the tell-tale hole, indicating the point in time and frequency, at which the light pendulum changes its role from driving to being driven. Going back to the physical interpretation of the mechanical model, this is the point in time at which the polarization created inside the QDs starts to induce additional excitations in the photon field.

(a) A qualitative analogue of the coupled light field-QD dynamics by two coupled pendula. (b,c) Amplitude and phase of the driving excitation (black), the light pendulum (red) and the QD pendulum (blue). (d) Envelope and relative phase of the convolution of excitation dynamics and light pendulum dynamics. The fast oscillations are removed. (e) Gabor surface derived for the data of d.

The typical patterns of the pulse shape modifications discussed for the driven pendula appear also in case of the QD system coupled to a carrier reservoir with electrical injection and optical driving pulse, as presented in the beginning (see Fig. 2). This case is clearly beyond the simple mechanical oscillator picture owing to the complex Coulomb scattering dynamics of the QDs coupled to a 2D reservoir; yet the basic processes of the coherent interaction between field and polarization inside the QDs leave their identifiable traces. In our device, by electrically populating the QD states, we can vary the initial QD carrier population from the absorbing regime through the transparency into the amplifying regime. This corresponds to largely unpopulated QDs, to an equal distribution of populated and unpopulated QDs, and to a majority of populated QDs. The resulting changes in the pulse envelope modulation are shown in Fig. 2b–d. For zero injection current the modifications of electric field amplitude, phase and Gabor surface are clearly visible (Fig. 2b). At intermediate current levels about the transparency current J0, these patterns disappear (Fig. 2c). Entering the amplifying regime, the pulse modification reappears (Fig. 2d). Even at high injection currents that lead to an increasing reservoir filling and thus to a shortened dephasing time T2 (ref. 22), the pulse shape modulation is still present (Fig. 2e). This behaviour is consistent with the assumption of a coherent energy transfer between QDs and optical field. Depending on the initial population of the QDs, the Rabi oscillations are phase shifted by half a cycle, in one case starting with absorption of light energy and in the other case starting with amplification by stimulated emission, controlled in the experiment by setting the appropriate injection current J. A net effect is thus only visible if the QDs are predominantly either populated with carriers or unpopulated (Fig. 2b,c), in the case of transparency the two anti-phase oscillations are expected to cancel, as they do in the experimental data of Fig. 2c. The dynamics of the coupled QD polarization and population is clearly seen via its back action on the exciting light field.

Figure 4 displays the results of the numerical simulations regarding the dynamics of the inversion and the polarization inside the QDs. In a two-level system, this is usually visualized using the Bloch sphere, based on a coordinate system spanned by the degree of population inversion and complex microscopic polarization, that is, the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix containing the time-dependent terms of the coherent dynamics5. For resonant light–matter interaction, the dynamics in the Bloch sphere is restricted to the plane spanned by inversion and imaginary part of the polarization. For a better visualization, the figure shows the total polarization but only the population dynamics of the QD sub-ensemble resonant to the driving laser pulse (the dynamics of the other QD subgroups is discussed later). The trajectories shown in the Bloch sphere in Fig. 4 correspond to the experimental conditions of Figs 2a–e and reflect the interaction with the modified laser pulse. At zero current (Fig. 4a), no charge carriers populate the QDs, and the Rabi oscillations start from the south pole of the Bloch sphere with an amplitude governed by the pulse area Θ of the driving laser pulse. Charge-carrier scattering processes as well as phase shifts of the polarization within the inhomogeneously broadened ensemble lead to a damping of the oscillations along the device (inset in Fig. 4a). For a partially or fully inverted system, the starting point of the coherent population oscillations is in the Northern Hemisphere of the Bloch sphere (Fig. 4b, coherent dynamics at the input facet of the device). The pulse amplification results in the rotation of the Bloch vector becoming increasingly fast during the pulse propagation, reflected in the number of cycles completed by the population in Fig. 4c at the output facet. In the intermediate case of partially filled QDs, the pulse drives at the same time two anti-phase Rabi oscillations, one starting from the lower and the other from the upper state of the two-level system with effectively disappearing signature on the pulse envelope. At high injection current, we see the impact of the injection current and corresponding high carrier density in the 2D reservoir as a reduced dephasing time T2 leading to a weaker contrast in the pulse modulation.

The Bloch vector of the resonant QD ensemble moves in the plane spanned by inversion and imaginary part of the polarization. The starting point of the oscillations is marked by an arrow. (a) Bloch vector for weak (solid violet) and strong (dashed cyan) pulse at J=0 at the input facet. The inset shows the magnified Bloch vector dynamics at the output facet. (b,c) Bloch vectors at input and output facets, respectively, for J=3J0 (solid blue), J=20J0 (dashed green) and J=30J0 (dash-dotted red).

It may seem surprising that clear pulse shape modulations are present even in the inhomogeneously broadened QD ensemble of our QD-SOA, but it will become clear by the following discussion of the dynamics of all different QD subgroups that are separately included in our modelling and displayed in Fig. 5b–f. The red and black lines in Fig. 5a and d represent the calculated electric field envelope and the convolution of the electric field with a reference field equal to the input pulse, at the input and output facets of the device, respectively. Note that the electric field (red line) of the pulse propagating through the sample is significantly distorted. The convolution with the Gaussian reference is causing a smoothing of this pulse shape modification, and translates the electric field reshaping into a dip in the tail of the black convolution curve. The colour-coded contour plots in the second and third row of Fig. 5 visualize the time evolution of the microscopic polarization amplitude of the QD ground states (GSs) for all subgroups of the inhomogeneously broadened ensemble (distinguished by their detuning in Fig. 5b,e), as well as the corresponding GS inversion for all contributing subgroups (Fig. 5c,f). Inspecting the simulated results of Fig. 5b, it becomes visible that at first a polarization is built up by the incoming optical pulse for all subgroups, but with a much higher amplitude for the group in resonance with the impinging light field (see bright yellow structure at t=0). All polarizations then decay with the dephasing time T2 and thus the bright structure centred around the initial detuning of 6 meV disappears. The polarization, in turn, reduces the GS inversion of the QDs by stimulated emission. In our case, the input pulse power is strong enough to drive the carrier occupations of the central subgroups below transparency, as evident from the blue area where the sign of the inversion is reversed in Fig. 5c. This zero crossing reflects a partial Rabi flop. At the output facet (Fig. 5f), the Rabi oscillations are faster because of the increased field amplitude and thus the blue area with negative inversion is compressed in time. The faster Rabi oscillations can also be seen in the polarization dynamics in Fig. 5e. Note that the dynamics of the polarization of the negatively and positively detuned subgroups is not symmetric around the initial detuning of 6 meV owing to the additional frequency components and chirp of the pulse induced along the propagation, which leads to a non-uniform excitation of the individual subgroups.

(a) Electric field amplitude Ep (red line) and cross correlation with an unmodified reference pulse (black line) of the input pulse. Panels b and c show polarization amplitude and inversion (colour coded) in dependence on the QD subgroup detuning Δω and time at the input facet. Panels d–f show the respective data at the output facet. Peak frequencies of light pulse and inhomogeneous distribution are detuned by 6 meV. The blue-dashed line in d indicates the resulting electric field cross correlation if the polarization dynamics is adiabatically eliminated. Input pulse area: Θ=1.15π.

The electric field is driven by the total polarization of the inhomogeneously broadened QD ensemble, and thus by a superposition of the polarization of all the different subgroups. Consequently, the spectral broadening translates into an additional dephasing of the polarization, which, for the case of a uniform occupation of all QDs, would resemble a Gaussian decay with a time constant of 73 fs. Thus, by introducing an additional dephasing process, the observed coherent signature could in principle also be reproduced with a simple two-level system using effective parameters. Certainly, as verified with our numerics, such an approach cannot accurately describe the observed pump-current dependence of the pulse modulation, for example, the reappearing and disappearing dips in the convoluted signal as well as the gradual loss of coherence at high injection currents. Here a pure dephasing process associated with the current-dependent process in the 2D reservoir accelerates the macroscopic polarization decay and yields T2 times below 100 fs (ref. 23). The limit of instantaneous dephasing is illustrated in Fig. 5d. The blue-dashed line in Fig. 5d represents the calculated electric field convolution at the output facet for the approximation of adiabatically eliminated polarization dynamics31, yielding an incoherent rate equation approach. Clearly, without the coherent polarization dynamics, the observed pulse shape cannot be reproduced.

Methods

Experimental methods

The device contains 15 undoped QD-in-a-well layers with a nominal QD density of 1011 cm−2 separated by 33–35 nm thick GaAs spacers. The shallow etched waveguide provides gain guiding on current injection, with the top contact defining an active region with a lateral extension of 2 μm. The length of the waveguide is 1.5 mm. The injection current can be varied from 0 to 200 mA, corresponding to 4.4 kA cm−2. When pumped electrically, the device shows amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) from the QD GS centred at 1,281 nm (0.967 eV), which is well described by a Gaussian with a FWHM of 0.03 eV. From pump-probe experiments, the GS transparency current is determined to be J0=5 mA at 1,280 nm. ASE data show that at injection currents above 16J0 (80 mA), the GS reaches the maximal inversion and the GS luminescence intensity saturates.

In the FROSCH experiment, the laser pulse is split into a probe (Ep) and a reference (Er) part in an acousto-optical modulator. The temporal delay τ between the two pulses is controlled by a delay stage, and recorded via the interference pattern of a control diode, analogous to rapid-scan Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. The beating generated by probe and reference pulse is recorded on two photodetectors in a balanced detection scheme. The detected intensity is filtered by a fast lock-in amplifier (Perkin Elmer DSP 7280). The lock-in signal S(τ)∝∫Ep(t)Er(τ−t)dt is the temporal convolution of the electric fields of reference pulse and probe pulse.

Numerical simulations

The Maxwell–Bloch model consists of coupled coherent optical Bloch equations for the QD inter-band polarizations pm and the carrier occupation probabilities ρb,mj for each subgroup j of QDs inside the inhomogeneously broadened QD ensemble.The dynamical equations in the slowly varying envelope and rotating wave approximation are given by:

The subscript bε{e,h} labels electrons and holes, respectively, and mε{GS,ES} labels the confined QD levels, GS and excited state, respectively (with degeneracy νm). We assume Gaussian distributions of the QD subgroups around the GS and ES centre frequencies, respectively, with a spectral FWHM of ΔE=30 meV in agreement with experimental ASE results. The QD states are coupled to a 2D carrier reservoir, represented by a QW-like wetting layer, by means of Auger scattering rates in the order of 1–10 ps−1 denoted by (∂ρb,mj)/(∂t)|col in equations (3) and (4). They take into account all possible carrier–carrier in- and out-scattering processes between QD and reservoir states, and are calculated microscopically via density matrix theory32,33, yielding a strong dependence on the carrier densities wb in the reservoir34. The Bloch equations (2)–(4), for the local response of the medium are coupled to the reduced travelling wave equation for the light propagating through the amplifier35,36.

The source for the light propagation described by equation (5) is the macroscopic polarization defined by P(z,t)=2NQD∑j,mνmf(j)(μ)/(hQW) (z,t), where NQD is the QD density, f(j) denotes the probability to find a QD in the jth subgroup and hQW=4 nm is the height of the QW layer. Further, vg is the group velocity, Δωmj=(ωmj−ω) is the detuning of the input light field frequency ω to the frequency ωmj of the respective optical transition in the jth subgroup37. Ω(t)=(μ)/(ħ)E(t) is the Rabi frequency with the slowly varying electric field amplitude E, the dipole moment μ=0.6 e0nm and the electron charge e0. We assume a linear increase of the confinement factor Γ from 0.2 to 0.3 between J=0 and J=30J0 to account for gain-guiding effects with increasing gain. The interaction strength of the electric field with the medium is proportional to the field amplitude. Thus, the pulse area Θ=∫(μ)/(ħ)E(0,t)dt is used to quantify the total interaction strength of the input pulse. It is noted that by neglecting inhomogeneous broadening, the coupling to the surrounding carrier reservoir and the light propagation, our system of dynamical equations can be traced into the well-known optical Bloch equations with the off-diagonal elements p and p*, and the diagonal elements ρe and ρh.

(z,t), where NQD is the QD density, f(j) denotes the probability to find a QD in the jth subgroup and hQW=4 nm is the height of the QW layer. Further, vg is the group velocity, Δωmj=(ωmj−ω) is the detuning of the input light field frequency ω to the frequency ωmj of the respective optical transition in the jth subgroup37. Ω(t)=(μ)/(ħ)E(t) is the Rabi frequency with the slowly varying electric field amplitude E, the dipole moment μ=0.6 e0nm and the electron charge e0. We assume a linear increase of the confinement factor Γ from 0.2 to 0.3 between J=0 and J=30J0 to account for gain-guiding effects with increasing gain. The interaction strength of the electric field with the medium is proportional to the field amplitude. Thus, the pulse area Θ=∫(μ)/(ħ)E(0,t)dt is used to quantify the total interaction strength of the input pulse. It is noted that by neglecting inhomogeneous broadening, the coupling to the surrounding carrier reservoir and the light propagation, our system of dynamical equations can be traced into the well-known optical Bloch equations with the off-diagonal elements p and p*, and the diagonal elements ρe and ρh.

The spontaneous recombination rate is given by Wmρe,mjρh,mj with the Einstein coefficient Wm. J is the electric current density injected into the QW and BS=540 nm2 ns−1 is a bimolecular loss rate accounting for spontaneous recombination between the QW bands. The decay of the microscopic polarization  is described by the dephasing rate (T2)−1≡(

is described by the dephasing rate (T2)−1≡( )−1+(

)−1+( )−1, which dynamically depends on the charge-carrier density in the device22. In addition to the Coulomb scattering contribution to dephasing,

)−1, which dynamically depends on the charge-carrier density in the device22. In addition to the Coulomb scattering contribution to dephasing,  , which is in the order of 50–500 fs depending on the pump current, we assume a constant phonon contribution given by (

, which is in the order of 50–500 fs depending on the pump current, we assume a constant phonon contribution given by ( )−1=3 ps−1. A modulation of the pulse amplitude is only visible in the output pulse if a pulse area of at least Θ≈π is transmitted during the time T2.

)−1=3 ps−1. A modulation of the pulse amplitude is only visible in the output pulse if a pulse area of at least Θ≈π is transmitted during the time T2.

We calculate the pulse propagation along the SOA and the dynamical behaviour of the QD gain medium by solving equations (2)–(5). The input pulse amplitude is modelled as a Gaussian with a FWHM of 235 fs and a peak frequency red shifted by 6 meV with regard to the GS gain peak, in accordance with experimental data.

Reducing the complete model to a skeleton of a two-level system is possible by assuming a vanishing inhomogeneous broadening (only one subgroup, no index j), neglecting carrier scattering and coupling of QD states to a non-equilibrium reservoir, and excited states in the QDs (no index m), assuming constant inversion in the GS (ρe+ρh−1=const.) and ignoring propagation effects. Doing so, the equations (2)–(5), can be transformed into equations formally identical to equations describing coupled harmonic oscillators as detailed below in the Mechanical analogue section.

Mechanical analogue

In our mechanical analogue, we describe the dynamics of two coupled and driven pendula as an analogue for the local response of the QDs to an impinging light field. The real part of the polarization of the two-level systems formed by the QDs in the experiment is represented as harmonic oscillator with eigenfrequency ωQD. This oscillator is coupled to a pendulum representing the light field that is modelled by a harmonic oscillator with eigenfrequency ωL. The effective dipole coupling between both is modelled via an elastic spring with coupling constant D. The light field oscillator in turn is resonantly driven by a laser excitation, following in its amplitude and phase the shape of the injected pulse. This system is described by a set of coupled differential equations

Here xL and xQD are the displacements of light oscillator and QD oscillator, respectively. β is a damping constant introduced to mimic the lifetime of the polarization and xlaser(t)∝K sin(ωLt)exp(−(t/τpulse)2) is the external oscillator, which drives the light pendulum with frequency ωL modulated by a Gaussian envelope in time with a width of τpulse. K represents the coupling constant of light field and laser excitation. The equations are solved numerically using SciLab version 5.4.0.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kolarczik, M. et al. Quantum coherence induces pulse shape modification in a semiconductor optical amplifier at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 4:2953 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3953 (2013).

References

Ladd, T. D. et al. Quantum computers. Nature 464, 45–53 (2010).

Walther, H., Varcoe, B. T. H., Englert, B. G. & Becker, T. Cavity quantum electrodynamics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 69, 1325–1382 (2006).

Wiseman, H. M. & Milburn, G. J. Quantum Measurement and Control Cambridge University Press (2000).

Brif, C., Chakrabarti, R. & Rabitz, H. Control of quantum phenomena. Adv. Chem. Phys. 148, 1–76 (2012).

Allen, L. & Eberly, J. H. Optical Resonance and Two-Level Atoms Wiley (1975).

Zrenner, A. et al. Coherent properties of a two-level system based on a quantum-dot photodiode. Nature 418, 612–614 (2002).

Luckyanova, M. N. et al. Coherent phonon heat conduction in superlattices. Science 338, 936–939 (2012).

Vasa, P. et al. Real-time observation of ultrafast Rabi oscillations between excitons and plasmons in metal nanostructures with J-aggregates. Nat. Photonics 7, 128–132 (2013).

Choi, H. et al. Ultrafast Rabi flopping and coherent pulse propagation in a quantum cascade laser. Nat. Photonics 4, 706–710 (2010).

Gomis-Bresco, J. et al. Impact of Coulomb scattering on ultrafast gain recovery in InGaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 256803 (2008).

Meuer, C. et al. 80 Gb/s wavelength conversion using a quantum-dot semiconductor optical amplifier and optical filtering. Opt. Express 19, 5134–5142 (2011).

Matsuura, M., Raz, O., Gomez-Agis, F., Calabretta, N. & Dorren, H. J. S. Ultrahigh-speed and widely tunable wavelength conversion based on cross-gain modulation in a quantum-dot semiconductor optical amplifier. Opt. Express 19, B551–B559 (2011).

Cundiff, S. T. et al. Rabi flopping in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1178–1181 (1994).

Schülzgen, A. et al. Direct observation of excitonic Rabi oscillations in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 2346–2349 (1999).

Stievater, T. H. et al. Rabi oscillations of excitons in single quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 133603 (2001).

Kamada, H., Gotoh, H., Temmyo, J., Takagahara, T. & Ando, H. Exciton Rabi oscillations in a single quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 246401 (2001).

Borri, P. et al. Rabi oscillations in the excitonic ground-state transition of InGaAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 66, 081306 (2002).

Bimberg, D. Semiconductor Nanostructures Springer (2008).

Grundmann, M., Stier, O. & Bimberg, D. InAs/GaAs pyramidal quantum dots: strain distribution, optical phonons, and electronic structure. Phys. Rev. B 52, 11969–11981 (1995).

Woggon, U. Optical Properties of Semiconductor Quantum Dots Springer (1996).

Lüdge, K. Nonlinear Laser Dynamics—From Quantum Dots to Cryptography Wiley-VCH (2011).

Koprucki, T., Wilms, A., Knorr, A. & Bandelow, U. Modeling of quantum dot lasers with microscopic treatment of Coulomb effects. Opt. Quant. Electron. 42, 777–783 (2011).

Borri, P. et al. Exciton relaxation and dephasing in quantum-dot amplifiers from room to cryogenic temperature. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. 8, 984–991 (2002).

Schneider, S. et al. Self-induced transparency in InGaAs quantum-dot waveguides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 3668–3670 (2003).

Zhang, J. Z. & Galbraith, I. Rabi oscillations of ultrashort optical pulses in 1.55μm InGaAs/InGaAsP quantum-well amplifiers. J. Appl. Phys. 96, 922–924 (2004).

Zhang, J. Z. & Galbraith, I. Rabi oscillations for subpicosecond pulses in quantum-well optical amplifiers: interplay of carrier heating, nonlinear, and spectral effects. IEEE J. Quantum Elect. 41, 1083–1091 (2005).

Capua, A., Karni, O., Eisenstein, G. & Reithmaier, J. P. Electron wavefunction probing in room-temperature semiconductors: direct observation of Rabi oscillations and self-induced transparency. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1210.6803 (2012).

Haug, H. & Koch, S. W. Quantum theory of the optical and electronic properties of semiconductors World Scientific (1994).

Ning, C. Z., Indik, R. A. & Moloney, J. V. Effective Bloch equations for semiconductor lasers and amplifiers. IEEE J. Quantum Elect. 33, 1543–1550 (1997).

Hughes, S., Knorr, A. & Koch, S. W. Femtosecond pulse breakup in a semiconductor amplifier. Opt. Lett. 21, 1052–1054 (1996).

Lingnau, B., Lüdge, K., Chow, W. W. & Schöll, E. Failure of the alpha factor in describing dynamical instabilities and chaos in quantum-dot lasers. Phys. Rev. E 86, 065201(R) (2012).

Lüdge, K. & Schöll, E. Quantum-dot lasers—desynchronized nonlinear dynamics of electrons and holes. IEEE J. Quantum Elect. 45, 1396–1403 (2009).

Majer, N., Lüdge, K. & Schöll, E. Cascading enables ultrafast gain recovery dynamics of quantum dot semiconductor optical amplifiers. Phys. Rev. B 82, 235301 (2010).

Majer, N. et al. Impact of carrier-carrier scattering and carrier heating on pulse train dynamics of quantum dot semiconductor optical amplifiers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 131102 (2011).

Knorr, A., Binder, R., Lindberg, M. & Koch, S. W. Theoretical study of resonant ultrashort-pulse propagation in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. A 46, 7179–7186 (1992).

Binder, R. & Koch, S. W. Nonequilibrium semiconductor dynamics. Prog. Quant. Electron 19, 307–462 (1995).

Majer, N., Lüdge, K. & Schöll, E. Maxwell-Bloch Approach to Four-Wave Mixing in Quantum Dot Semiconductor Optical Amplifiers in 11th Internat. Conf. on Numerical Simulation of Optoelectronic Devices (NUSOD), Rome 2011 (ed. Piprek J. 153–154 (IEEE, 2011).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge fruitful discussions with Holger Schmeckebier. This work was supported by DFG within SFB 787. M.K. additionally acknowledges support from GRK 1558.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K., N.O. and Y.K. designed and performed the experiments. J.K. and B.L. carried out simulations. D. B. provided the device. U.W., E.S. and K.L. initiated and coordinated the project. All authors contributed to data analysis, interpretation and conclusions, and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kolarczik, M., Owschimikow, N., Korn, J. et al. Quantum coherence induces pulse shape modification in a semiconductor optical amplifier at room temperature. Nat Commun 4, 2953 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3953

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3953

This article is cited by

-

Stable coherent mode-locking based on \(\pi\) pulse formation in single-section lasers

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Ultrafast terahertz saturable absorbers using tailored intersubband polaritons

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Ultra-Short Pulse Generation in a Three Section Tapered Passively Mode-Locked Quantum-Dot Semiconductor Laser

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Rabi-oscillation-enhanced frequency conversion in quantum-dot semiconductor optical amplifiers

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2018)

-

Population density gratings induced by few-cycle optical pulses in a resonant medium

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.