Abstract

The kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) is an economically and nutritionally important fruit crop with remarkably high vitamin C content. Here we report the draft genome sequence of a heterozygous kiwifruit, assembled from ~140-fold next-generation sequencing data. The assembled genome has a total length of 616.1 Mb and contains 39,040 genes. Comparative genomic analysis reveals that the kiwifruit has undergone an ancient hexaploidization event (γ) shared by core eudicots and two more recent whole-genome duplication events. Both recent duplication events occurred after the divergence of kiwifruit from tomato and potato and have contributed to the neofunctionalization of genes involved in regulating important kiwifruit characteristics, such as fruit vitamin C, flavonoid and carotenoid metabolism. As the first sequenced species in the Ericales, the kiwifruit genome sequence provides a valuable resource not only for biological discovery and crop improvement but also for evolutionary and comparative genomics analysis, particularly in the asterid lineage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Actinidiaceae, the basal family within the Ericales, consists of the genera Actinidia, Saurauia and Clematoclethra1. The genus Actinidia, commonly known as kiwifruit, includes several economically important horticultural species, such as Actinidia chinensis Planchon, A. deliciosa (A. chinensis var. deliciosa A. Chevalier), A. arguta (Siebold and Zuccarini) Planchon ex Miquel and A. eriantha Bentham2. Approximately 54 species and 75 taxa have been described in Actinidia3, all of which are perennial, deciduous and dioecious plants with a climbing or straggling growth habit. The kiwifruit species are often reticulate polyploids with a base chromosome number of x=29 (ref. 4).

The kiwifruit has long been called ‘the king of fruits’ because of its remarkably high vitamin C content and balanced nutritional composition of minerals, dietary fibre and other health-beneficial metabolites. Extensive studies on the metabolic accumulation of vitamin C, carotenoids and flavonoids have been reported in kiwifruits5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. The centre of origin of kiwifruit is in the mountains and ranges of southwestern China. The kiwifruit has a short history of domestication, starting in the early 20th century when its seeds were introduced into New Zealand14. Through decades of domestication and substantial efforts for selection from wild kiwifruits, numerous varieties have been developed and kiwifruits have become an important fresh fruit worldwide with an annual production of 1.44 million tons in 2011 ( http://faostat.fao.org).

Despite the availability of an extensive expressed sequenced tag (EST) database15 and several genetic maps16,17, whole-genome sequence resources for the kiwifruit, which are critical for its breeding and improvement, are very limited. Kiwifruit belongs to the order Ericales in the asterid lineage. Currently, no genomes have been sequenced for species in the Ericales and in the asterid lineage only the genomes of Solanaceae species in the order Euasterids I, including the tomato18 and potato19, have been sequenced.

Here we sequence and analyse the genome of a heterozygous kiwifruit, ‘Hongyang’ (A. chinensis), which is widely grown in China. The availability of this genome sequence not only provides insight into the underlying molecular basis of specific agronomically important traits of kiwifruit and its wild relatives but also presents a valuable resource for elucidating evolutionary processes in the asterid lineage.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly

One female individual of a Chinese kiwifruit cultivar ‘Hongyang’ was selected for whole-genome sequencing. ‘Hongyang’ is a heterozygous diploid (2n=2x=58) that is derived from clonally selected wild germplasm in central China and has not been subjected to further selection and breeding20. Its oval shaped fruit has a hairy, greenish-brown skin, a slight green or golden outer pericarp and a red-flesh inner pericarp with rows of tiny, black, edible seeds. Its fruit is highly nutritional containing abundant levels of ascorbic acid (vitamin C), carotenoids, flavonoids and anthocyanins (Supplementary Table S1).

A total of 105.8 Gb high-quality sequences (Supplementary Table S2) were generated using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 system. This represented approximately a 140 × coverage of the kiwifruit genome with an estimated size of 758 Mb based on the flow cytometry analysis21. De novo assembly of these sequences employing Allpaths-LG22 yielded a draft genome of 616.1 Mb, representing 81.3% of the kiwifruit genome (Table 1). The genome assembly consists of 21,713 contigs and 5,110 scaffolds (>2 kb), with N50 sizes of 58.8 and 646.8 kb for contigs and scaffolds, respectively (Table 1). To determine scaffold placement on kiwifruit pseudochromosomes, a high-density genetic map was constructed using an F1 population derived from the cross between ‘Hongyang-MS-01’ (male) and A. eriantha ‘Jiangshanjiao’ (female). Genotyping of each individual in the F1 population was determined using SLAF-seq23. The final map spanned 5,504.5 cM across 29 linkage groups and was composed of 4,301 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers, with a mean marker density of 1.28 cM per marker. Using 3,379 markers that were uniquely aligned to the assembled scaffolds, a total of 853 scaffolds were anchored to the 29 kiwifruit pseudochromosomes, comprising 73.4% (452.4 Mb) of the kiwifruit genome assembly (Fig. 1). Of the 853 anchored scaffolds, 491 could be oriented (333.6 Mb, 73.7% of the anchored sequences).

The GC content of the assembled genome was 35.2%, similar to that of the genomes of tomato (34%)18 and potato (34.8%)19, which to date are the evolutionarily closest species of kiwifruit that have genomes sequenced (Supplementary Fig. S1). Furthermore, we detected heterozygous sites by mapping the reads back to the assembled genome, revealing a high level of heterozygosity (0.536%) in ‘Hongyang’, which was further supported by the K-mer distribution of the genomic reads (Supplementary Fig. S2).

To evaluate the quality of the assembled genome, an independent Illumina library with an insert size of 500 bp was constructed and sequenced. The resulting reads were mapped to the assembled genome to identify homozygous SNPs and structure variations (SVs), which represent potential base errors and misassemblies in the genome, respectively. The analyses indicated that the assembly has a single base error rate of 0.03%, which is comparable to the rate of the tomato genome (0.02%)18. In addition, only 24 SVs were identified (Supplementary Table S3), indicating a very low frequency of misassemblies in the genome. The quality of the assembly was further assessed by aligning the EST sequences from the genus Actinidia15 to the assembled genome. The analysis indicated that the assembly contained 97.3% of the 81,956 ESTs derived from A. chinensis, 90.9% of the 83,924 ESTs from A. deliciosa and 94.3% of the 19,574 ESTs from A. eriantha (Supplementary Table S4). Together, these analyses supported the high quality of our genome assembly.

Repetitive sequence annotation

We identified a total of ~222 Mb (36% of the assembly) of repetitive sequences in the kiwifruit genome. The content of repetitive sequences in the kiwifruit genome appears to be much less than that in tomato (63.2%)18 and potato (62.2%)19, whereas it is more than that in Arabidopsis (14%)24 and Thellungiella parvula (7.5%)25.

Comparative analysis with known repeats in Repbase26 and plant repeat database27 indicated that 68.8% of the repetitive sequences in the kiwifruit genome could be classified and annotated. A large portion of the unclassified repetitive sequences might be kiwifruit-specific. Retrotransposons made up the majority of the repeats, among which the long terminal repeat (LTR) family was the most abundant (~13.4% of the assembly). Within the LTR family, Copia and Gypsy represented the two most abundant subfamilies. In addition, DNA transposons accounted for ~4.75% of the genome assembly (Supplementary Table S5).

Gene prediction and annotation

Using the EST sequences of A. chinensis15 and RNA-seq data we have generated from A. chinensis leaf and fruits (Supplementary Fig. S3), integrated with ab initio gene predictions and homologous sequence searching, we predicted a total of 39,040 protein-encoding genes with an average coding sequence length of 1,073 bp and 4.6 exons per gene. Among these genes, 74.5 and 82.3% had significant similarities to sequences in the non-redundant nucleotide and protein databases in NCBI, respectively. Additionally, 37.4, 66.9, 81.9, 61.3 and 81.8% could be annotated using COG, GO, TrEMBL, Swissprot and KEGG databases, respectively. Furthermore, conserved domains in >65.5% of the predicted protein sequences could be identified by comparing them against InterPro and Pfam databases. In addition, a total of 2,438 putative transcription factors that are distributed in 58 families and 447 transcriptional regulators distributed in 22 families were identified in the kiwifruit genome (Supplementary Data 1 and 2). In addition to protein-coding genes, 293 rRNAs, 511 tRNAs, 236 miRNAs, 91 snRNAs and 307 SnoRNAs were also identified.

Comparative analyses between kiwifruit and other plants

Comparative analyses of the complete gene sets of kiwifruit, Arabidopsis, rice, grape and tomato were performed. A total of 25,381 genes in the kiwifruit genome were assigned into 13,100 orthologous gene clusters. Among these clusters, 7,985 are common to all five species, whereas 885 are confined to eudicots (kiwifruit, Arabidopsis, grape and tomato). Within the eudicots, 337 gene clusters are restricted to plants with flesh fruits (kiwifruit, grape and tomato), whereas 1,455 clusters contain genes only from kiwifruit (Fig. 2). Further functional characterization based on GO terms revealed that the 337 flesh fruit-specific families were highly enriched with genes associated with fruit quality, including those related to flavonoid, phenylpropanoid, anthocyanin and oligosaccharide metabolism (Supplementary Table S6). The kiwifruit-specific families were significantly enriched with genes related to pollen tube reception and specification of floral organ identity (Supplementary Table S7), both of which are consistent with the high diversity of sex expression found in kiwifruit17,28.

Among plants with the sequenced genomes, tomato has the closest evolutionary relationship to kiwifruit. Consequently, the largest number of gene clusters (10,849) were shared between kiwifruit and tomato, representing 82.8 and 82.5% of their individual total gene clusters, respectively. We then calculated the evolutionary rate for each of the orthologous gene pairs of kiwifruit–grape, Arabidopsis–grape and tomato–grape. The average ratio (ω) of non-synonymous (Ka) versus synonymous (Ks) nucleotide substitution rate in kiwifruit (0.064) was found to be greater than that in Arabidopsis (0.055) and tomato (0.052), indicating that diversifying selection may have been stronger in kiwifruit.

Whole-genome duplication in kiwifruit

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) followed by gene loss has been found in most eudicots and is regarded as the major evolutionary force that gives rise to gene neofunctionalization in both plants and animals. Within the kiwifruit genome, 588 paralogous relationships were identified, covering 46% of the genome. We then compared the kiwifruit genome sequence to that of tomato, potato and grape, respectively, and identified a large number of syntenic regions (Fig. 3a). The distribution of 4DTv (transversions at fourfold degenerate sites) and Ks values of homologous pairs in these syntenic regions, as well as the mean Ks values of individual syntenic blocks indicated that an ancient WGD (the γ event), which is shared by core eudicots, and two recent WGD events had occurred in the evolutionary history of kiwifruit (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S4a–c). In addition, using the method described in Simillion et al.29, we were able to group kiwifruit syntenic blocks into three age classes based on their mean Ks values, further supporting the ancient triplication and the two recent WGD events in kiwifruit (Supplementary Fig. S4d). The two recent WGD events, Ad-α and Ad-β, were estimated to have occurred ~26.7 and 72.9–101.4 million years ago, respectively, based on Ks of paralogous genes. These results are consistent with previous findings based on the EST analysis30. Both Ad-α and Ad-β events occurred after the kiwifruit–tomato or kiwifruit–potato divergence (Fig. 3b).

The relationship of orthologous genes in syntenic blocks between kiwifruit and grape was further analysed. We found that 55.8% of kiwifruit gene models are in blocks that are orthologous to one grape region, collectively covering 73.6% of the grape gene space. Among these grape genomic regions, 19.1% have one orthologous region in kiwifruit, 20.5% have two, 23% have three, 19.3% have four, 11% have five, 4.4% have six, 2.2% have seven and a few (<1%) have eight, nine and ten. This pattern is similar to that of Arabidopsis31, whose genome has also undergone two WGD (At-α and At-β) following the ancient γ triplication. These data further supported the occurrence of the two recent WGD events in kiwifruit, followed by extensive gene loss.

Gene expansion and neofunctionalization in kiwifruit

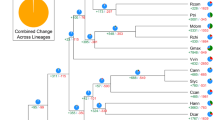

Kiwifruit is well known for its high nutritional value because of the extremely abundant content of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) in them. We investigated and compared genes involved in the ascorbic acid biosynthesis and recycling pathway in kiwifruit, Arabidopsis, grape, sweet orange and tomato. Although we found no expansion in genes from the L-galactose pathway that forms the major route to vitamin C biosynthesis in kiwifruit32, we did find that other gene families involved in ascorbic acid biosynthesis, including Alase (aldonolactonase), APX (L-ascorbate peroxidase) and MIOX (myo-inositol oxygenase), and genes responsible for ascorbic acid regeneration from its oxidized forms, including MDHAR (monohydroascorbate reductase), exhibited an expansion in kiwifruit (Supplementary Table S8 and Supplementary Fig. S5). Phylogenetic analyses of genes in these expanded families, combined with results from the synteny analyses, indicated that the two recent WGDs in kiwifruit resulted in additional gene family members that evolved to contribute to the high vitamin C accumulation in the fruit of kiwifruit (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs S6–S8). Most of the expanded genes in the ascorbic acid biosynthesis and recycling pathway were expressed in both leaves and fruits of kiwifruit, with a large portion being expressed higher in fruits (especially immature fruits) than in leaves (Supplementary Table S9). This is consistent with the high level of ascorbic acid in both fruits and leaves of ‘Hongyang’ and a higher level in immature fruits (Supplementary Table S1).

(a) Phylogenetic tree of monohydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR) genes from kiwifruit (green), Arabidopsis (blue), grape (purple), sweet orange (yellow) and tomato (red). Heatmaps representing expression levels of kiwifruit MDHAR genes in leaf, immature fruit, mature green fruit and ripe fruit (from left to right) are shown on the right of the tree. Log2-transformed gene expression values were used to generate heatmaps. (b) Microsynteny of genome regions surrounding kiwifruit MDHAR genes (Achn297231 and Achn389481), and their corresponding tomato (Solyc02g086710), potato (PGSC0003DMG400000486) and grape (GSVIVT01032453001) orthologues. MDHAR genes are shown in red. Genes with no syntenic homologue(s) are in white. Other syntenic genes are shown in different colours based on their presence/absence patterns in the genome regions.

Kiwifruit also contains high levels of other important nutritional compounds including carotenoids, flavonoids and chlorophylls (Supplementary Table S1). Compared with Arabidopsis, grape, sweet orange and tomato, expansions of gene families in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway, including lycopene beta-cyclase, lycopene epsilon-cyclase, phytoene desaturase and violaxanthin deepoxidase, were observed in kiwifruit (Supplementary Table S10 and Supplementary Fig. S9). In the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway, gene families including chalcone isomerase, flavanone 3-hydroxylase and flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase, were expanded (Supplementary Table S11 and Supplementary Fig. S10). Although no large-scale gene expansion events in chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation are evident in kiwifruit, an additional member encoding GluTR (Glutamyl-tRNA reductase) was found (Supplementary Table S12). GluTR is responsible for the biosynthesis of 5-aminolevulinic acid, the key precursor of chlorophyll33,34. Expression analyses indicated that almost all of the identified expanded genes in the carotenoid, flavonoid and chlorophyll metabolic pathways were expressed, exhibiting temporal and tissue specificity (Supplementary Tables S13–S15).

It is worth noting that unlike most other kiwifruit cultivars, ‘Hongyang’ fruits and leaves are also highly abundant in anthocyanins, one class of flavonoid compounds and responsible for the red colour of the inner pericarp of ‘Hongyang’ (Supplementary Table S1). It is not surprising that there is no expansion observed in kiwifruit for the key enzymes of anthocyanin biosynthesis including leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase/anthocyanidin synthase and UDP-glucose flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (Supplementary Table S11). Most genes in the leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase/anthocyanidin synthase and UDP-glucose flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase families were highly expressed in both immature fruits and leaves, indicating that anthocyanins might be mainly synthesized in the early development stage of fruits (Supplementary Table S14).

Disease-resistance genes in kiwifruit

Plants have evolved two layers of innate immunity to defend potential pathogens: pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity. PTI is a relatively ancient form that is triggered through the perception of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern-recognition receptors, whereas effector-triggered immunity is conferred through the recognition of pathogen-secreted effectors by the nucleotide-binding site and leucine-rich repeat (NBS–LRR) genes35. In the kiwifruit genome, a total of 96 NBS–LRR genes were identified (Supplementary Data 3), which was comparable to the number of NBS–LRR genes found in papaya (55)36 and watermelon (44)37 but considerably fewer than those in Arabidopsis (166)38, rice (~600)39, grape (504)40 and tomato (251)18. As particular NBS–LRR genes recognize specific pathogen effectors, the fewer number of NBS–LRR genes in kiwifruit may represent less potential for pathogen recognition. These data imply that NBS–LRR genes are not under strong selection pressure in kiwifruit, possibly because of fewer pathogens that have evolved to adapt to kiwifruit. The distribution of NBS–LRR genes in the kiwifruit genome is not random, as nearly one-third of them (27) are located in the genome within 10 clusters (Supplementary Data 3), suggesting that they have evolved mainly through tandem duplications, similar to what have been reported in other sequenced plant genomes37,38,39,40.

A total of 261 putative pattern-recognition receptor genes, which encode receptor-like kinases with an LRR domain (RLK–LRR), were identified in the kiwifruit genome (Supplementary Data 4). This number is larger than that found in Arabidopsis (220), grape (232) and tomato (236), suggesting that PTI, a type of ancient innate immunity, is more conserved in kiwifruit and may have an important role in defense against potential pathogens.

Discussion

A high-quality draft genome of a highly heterozygous kiwifruit cultivar ‘Hongyang’ has been successfully assembled, using the high coverage (~140 × ) of Illumina paired-end and mate-pair reads. The assembly covers about 81.3% of the kiwifruit genome. The kiwifruit genome sequence presented in this study represents the first genome sequence of a member in the order Ericales and the third in the entire asterid lineage, after potato and tomato, thus providing a valuable resource for comparative genomics and evolutionary studies, especially in the asterid lineage that has much less available genomic resources compared with the rosid lineage.

Besides the ancient hexaploidization event (γ) shared by core eudicots, kiwifruit appears to have undergone two additional independent WGD events. Both events occurred after the divergence of kiwifruit from tomato and potato. Whether these two WGD events are shared by other members of Actinidiaceae or the Ericales will require further analysis when more genome sequences from the family or order become available.

Kiwifruit is a rich source of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and other health-beneficial compounds. Our analyses demonstrated that extensive expansions have occurred in the members of gene families involved in the ascorbic acid biosynthetic and recycling pathway, the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway and the flavonoid metabolism pathway. The majority of these expansions can be attributed to at least one of the two recent WGD events, indicating that WGD has played an important role in adding new gene family members that mediate important fruit-specific attributes that contribute to the high nutritional value of kiwifruit.

The kiwifruit genome sequence will be an invaluable resource for the genetic improvement of kiwifruit and for better understanding of genome evolution. It will also be invaluable in developing new varieties and for resolving questions of agronomical and/or biological importance, such as those related to fruit development and ripening, fruit nutrient metabolism, disease resistance, sex determination and polyploidy evolution in kiwifruit and other related plant species.

Methods

Genome sequencing and assembly

High-quality genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves of a 5-year old, female plant of A. chinensis cv. Hongyang, growing in the farm of Sichuan Academy of Natural Resource Sciences, Sichuan Province, China. An improved CTAB method was used to prepare the kiwifruit genomic DNA. The modified CTAB extraction buffer included 0.1 M Tris-HCl, 0.02 M EDTA, 1.4 M NaCl, 3% (w/v) CTAB and 5% (w/v) PVP K40. Beta-mercaptoethanol was added to the CTAB extraction buffer to ensure DNA integrity and quality. RNase A and proteinase K were used to remove RNA and protein contamination, respectively. Paired-end and mate-pair Illumina genomic DNA libraries were constructed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, USA) using the prepared DNA from ‘Hongyang’. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 system. Raw reads were processed by removing PCR duplicates, low-quality reads, adaptor sequences and contaminated reads of bacterial or viral origin. Additionally, sequence errors were corrected based on the K-mer frequency. The resulting high-quality cleaned reads were assembled into contigs and scaffolds using Allpaths-LG22, based on the ‘de bruijn graph’ theory. Gaps within the scaffolds were filled using the GapCloser tool in the SOAPdenovo package41.

Genetic map construction and scaffold anchoring

An F1 population was generated from a cross between A. chinensis ‘Hongyang-MS-01’ (male) and A. eriantha ‘Jiangshanjiao’ (female). ‘Hongyang-MS-01’ is a male variety and is normally used as the pollinizer for the female cultivar ‘Hongyang’. Owing to the high heterozygosity in both parents, the F1 population could be considered as a double pseudo-testcross. A total of 300 individuals were obtained and 108 of them were used for genetic map construction.

High-quality genomic DNA was extracted from the 108 individuals and was used to construct Illumina sequencing libraries following the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina, USA). The genomic libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 system, and a total of 3.76 Gb of 80 bp reads were obtained. Average sequencing depths of sequenced loci per parent and per progeny were 78.63- and 10.73-fold, respectively. Genotyping and evaluation of the quality of genetic markers were performed as described in Sun et al.23 Briefly, the Illumina paired-end reads were first clustered into the same groups if they share at least 90% sequence identities. Alleles at each locus were then defined using the minimum allele frequency evaluation, and markers with more than four alleles were discarded. The accuracy of the genotyping was evaluated based on the coverage of each allele and the number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms at each locus. A total of 5,320 high-quality SNP markers were identified and used to construct the genetic map with the double pseudo-testcross strategy using JoinMap 4.0. Using the nearest-neighbour method, a total of 4,301 markers were clustered into 29 linkage groups, with LOD scores ranging from 4 to 20. The SNP markers were then aligned to the kiwifruit-assembled scaffolds, and only uniquely aligned markers were used to anchor and orient the scaffolds onto the 29 kiwifruit pseudochromosomes. The marker sequences are provided in Supplementary Data 5.

Quality assessment and heterozygous locus identification

An independent library with an insert size of 500 bp was constructed and sequenced to assess the quality of the genome assembly. Paired-end reads from this library were aligned to the kiwifruit genome assembly using BWA42. On the basis of the alignments, genotypes supported by at least 10 reads and with an allele frequency ⩾0.3 were assigned to each genomic position. Homozygous SNPs, which represent potential sequence errors in the assembly, were then identified. SVs, which represent potential misassemblies, were also identified using SVDetect43. To determine the coverage of gene space by the assembly, EST sequences of A. chinensis, A. deliciosa and A. eriantha15 were mapped to the genome assembly using BLASTN.

To identify heterozygous sites, reads from all four short-insert (insert size ⩽500 bp) Illumina paired-end libraries were aligned to the kiwifruit genome sequences using BWA42. Only read pairs that were uniquely aligned to the genome were kept. Following alignment, the coverage of each genomic position by bases A, G, C and T was calculated. Genomic loci containing at least two alleles with each of them supported by at least 20 reads and with allele frequency of at least 0.3 were identified as heterozygous loci in the kiwifruit genome. Adjacent heterozygous loci that were separated by <5 bp were discarded.

Identification of repetitive sequence

Repeat sequences in the kiwifruit genome were first identified using three de novo prediction programs, LTR_FINDER44, RepeatScout45 and PILER-DF46. The identified repeat sequences were used to construct a non-redundant repeat sequence library. Repeat sequences in the kiwifruit genome were then identified using Repeatmasker ( http://www.repeatmasker.org) and the constructed repeat sequence library. Additional repeat sequences were identified by comparing the assembled genome sequences against the Repbase database26 and the plant repeat database27, using BLAST with an e-value cutoff of 1e-5. Finally, repeat sequences with an identity ⩾50% were grouped into the same classes.

RNA-seq data generation and expression analysis

Mature leaves, immature fruits (20 days after pollination (DAP)), mature green fruits (120 DAP) and ripe fruits (127 DAP) were collected from a 5-year-old ‘Hongyang’ plant. Fresh tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to fine powder. Total RNAs were isolated using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) followed by treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. The quality of RNAs was checked using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Illumina RNA-Seq libraries were prepared and sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 system following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, USA). Two to three biological replicates were performed for the fruit samples. The resulting paired-end 90-bp- or single-end 50-bp RNA-seq reads were first aligned to ribosomal RNA and tRNA sequences in order to remove possible contaminations of these sequences. The cleaned reads were then aligned to the kiwifruit genome assembly using TopHat47. Following the alignment, raw counts for each kiwifruit gene model were derived and normalized to fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads48.

Gene prediction and annotation

The repeat-masked kiwifruit genome sequences were used for gene prediction. The gene prediction pipeline combined ab initio gene predictions, homologous sequence searching and transcriptome sequence mapping (including both ESTs and RNA-seq data). The results from the three independent methods were merged into the final consensus of gene models using Glean49. Specifically, GeneScan50 was employed for de novo gene prediction. Homologous sequence searching was performed by comparing protein sequences of Arabidopsis, rice, grape and tomato against the repeat-masked kiwifruit genome sequences using TBLASTN with parameters of identity ⩾60 and ⩾80% of the query sequence covered in the alignments. The corresponding kiwifruit genomic regions were retrieved, together with sequences 1 kb downstream and upstream of the aligned regions. The alignments were further processed using GeneWise51 to extract accurate exon–intron information. Illumina RNA-seq reads were assembled de novo into contigs using Trinity48. The resulting contig sequences, as well as A. chinensis EST sequences, were aligned to the repeat-masked kiwifruit genome sequences using BLAT52. Final gene sequences were derived through further analysis of the BLAT alignment results using PASA53.

Annotation of the predicted genes was performed by blasting their sequences against a number of nucleotide and protein sequence databases, including COG, InterPro, nt, nr, KEGG, Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL, using an e-value cutoff of 1e-5. Functions of the predicted kiwifruit genes were assigned using AHRD (Automated assignment of Human Readable Descriptions; https://github.com/groupschoof/AHRD) as described previously18. Briefly, the 200 top-scoring search results of kiwifruit-predicted proteins against Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, InterPro and Arabidopsis protein databases were scored based on alignment scores, expected quality of descriptions per database and a lexical scoring of individual ‘words’ computed from their frequency in the descriptions of top-scoring results. The highest-scoring description was assigned to each kiwifruit gene. GO terms were assigned to the annotated genes in kiwifruit and other sequenced plant species, including tomato, grape, apple and strawberry, using the Blast2GO pipeline54. tRNAs were identified using tRNAscan-SE55, and snRNAs and snoRNAs were identified by searching the genome assembly against the Rfam database using INFERNAL with default parameters ( http://infernal.janelia.org/). rRNAs were identified by searching the genome assembly using the Rfam database as a reference with a cutoff of at least 90% sequence identity and 80% coverage. Transcription factors/regulators were identified and classified into different families using the iTAK pipeline ( http://bioinfo.bti.cornell.edu/tool/itak).

Comparative analysis of gene sets

Protein sequences from kiwifruit, Arabidopsis, rice, grape and tomato were used to identify gene clusters. For those having spliced variants, only the variants with the longest protein sequences were used. Gene family clusters among different plant species were identified using OrthoMCL 1.4 (ref. 56). Pairwise sequence similarities between all protein sequences were calculated using BLASTP with an e-value cutoff of 1e-05. On the basis of the results of BLASTP, OrthoMCL was used to perform a Markov clustering algorithm to define the cluster structure, with a default inflation value (−I) of 1.5.

KaKs_Calculator57 was utilized to calculate the value under the evolution press. The phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA 5.0 using the neighbour-joining or maximum likelihood method58. The parameters used in the tree construction were the JTT model plus gamma-distributed rates and 1,000 bootstraps.

Comparative genomics analysis

All-to-all BLASTP analysis of protein sequences was performed between kiwifruit and grape, tomato, and potato, respectively, as well as within each species, using an e-value cutoff of 1e-10, coverage ⩾50% and identity ⩾20%. Syntenic regions within each species and between kiwifruit and grape, tomato and potato were then identified using MCscan31 based on the all-to-all BLASTP results. Protein sequences of homologous gene pairs in the identified syntenic regions were first aligned using MUSCLE59, and the protein alignments were then converted to the CDS alignments. Finally, 4DTV values were calculated on these CDS alignments and corrected using the HKY model, and Ks values were calculated using the Yn00 program in the PAML package60. The kiwifruit syntenic blocks were grouped into different age classes based on their mean Ks values using the method described in Simillion et al.29 Briefly, two duplication blocks were put into the same age class if the mean Ks values of both duplications did not differ significantly using a t-test (P<0.01). A candidate age class was formed by taking a first duplication and adding to it the duplication that resulted in the age class with the lowest coefficient of variance. This process continued until no further duplications could be added to the age class without exceeding a coefficient of variance value of 0.5. Next, a second candidate age class was formed by starting with a second duplication and repeating the process. These steps were repeated for the remaining duplications until no more age classes could be defined containing five or more blocks.

Nutrient metabolite determinations

The content of various metabolites, including starch, sugar, chlorophyll, flavonoids, anthocyanins, carotenoids and ascorbic acid (vitamin C), was determined in ‘Hongyang’ leaves and fruits (including both inner and outer pericarps) at 20 DAP, 120 DAP and 127 DAP. Three biological replicates were performed for each analysis. Starch content was measured using the starch iodine reaction61. Briefly, samples extracted with 18% HCl were stained with the I2-KI solution. After mixing, absorbance at 605 and 530 nM was measured. The starch content was estimated according to the standard curve generated by the two standards of amylose and amylopectin mixed in various ratios. Sugar content was determined using the anthrone method62, with glucose as the standard. Flavonoids were extracted in 95% ethanol by ultrasonic methods63. The level of flavonoids was measured using the aluminium chloride colorimetric method64, with rutin as the standard. Total anthocyanin content was determined by the method described in Di Stefano et al.65 Briefly, 1-g frozen sample was macerated twice to colourless with 25 ml extracting solvent (95% ethanol-0.l N HCl) at 50 °C. Ten millilitre of filtered extract was diluted to 50 ml with pH=1.0 (0.2 mol l−1 KCL-0.2 mol l−1 HCl-H2O) and pH=4.5 (19.294 g NaAc and 24 ml glacial acetic acid make up to 500 ml with ultrapure water) buffer solution, respectively. The diluted extract was stored in the dark for 100 min, and the optical density (OD) was measured at the absorption maxima of anthocyanins extract (530 nm). The anthocyanin content was calculated as X=(ΔOD × V × F × M × 1,000)/(ε × m). Where X=total anthocyanin content (mg g−1); OD=absorbancy reading on the diluted sample (1 cm cell); V=diluted volume (ml); F=dilution factor; M=molecular weight of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (449.38); ε=molar extinction coefficient of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (2.69 × 104); and m=sample weight. The content of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) was measured using the dinitrophenylhydrazine method66. Chlorophyll and carotenoids were repeatedly extracted in 80% aqueous acetone (10 ml) in darkness until the samples turned white. Absorbance was measured at 470, 663 and 645 nm, respectively. The relative content of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll and total carotenoids was then calculated using formulae described in Lichtenthaler et al.67 and Arnon68: total carotenoids (mg g−1)=(1,000 × A470–3.27 × chlorophyll a−104 × chlorophyll b)/229, chlorophyll a (mg g−1)=(12.7 × A663–2.69 × A645) × V/(1,000 × W), chlorophyll b (mg g−1)=(22.9 × A645–4.68 × A663) × V/(1,000 × W), total chlorophyll (mg g−1)=(8.02 × A663+20.20 × A645) × V/(1,000 × W), where V=volume of the extract (ml) and W=weight of fresh tissues (g).

Additional information

URLs. Kiwifruit Genome Database, http://bioinfo.bti.cornell.edu/kiwi; FAO Statistics database, http://faostat.fao.org

Accession codes: Sequence data have been deposited in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ nucleotide core database under the accession number AONS00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, AONS01000000. Sequence reads of transcriptome sequencing have been deposited in NCBI sequence read archive (SRA) under accession number SRA065642.

How to cite this article: Huang, S. et al. Draft genome of the kiwifruit Actinidia chinensis. Nat. Commun. 4:2640 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3640 (2013).

Accession codes

References

Dickison, W. C., Nowicke, J. W. & Skvarla, J. J. Pollen morphology of the Dilleniaceae and Actinidiaceae. Am. J. Bot. 69, 1055–1073 (1982).

Chat, J., Jauregui, B., Petit, R. J. & Nadot, S. Reticulate evolution in kiwifruit (Actinidia, Actinidiaceae) identified by comparing their maternal and paternal phylogenies. Am. J. Bot. 91, 736–747 (2004).

Li, J. Q., Li, X. W. & Soejarto, D. D. Actinidiaceae. inFlora of China eds Wu Z. Y., Raven P. H., Hong D. Y.) Vol 12, 334–362Science Press; Missouri Plant Garden Press (2007).

McNeilage, M. A. & Considine, J. A. Chromosome studies in some Actinidia taxa and implications for breeding. N. Z. J. Bot. 27, 71–81 (1989).

Ampomah-Dwamena, C. et al. The kiwifruit lycopene beta-cyclase plays a significant role in carotenoid accumulation in fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 3765–3779 (2009).

Laing, W. A. et al. A highly specific L-galactose-1-phosphate phosphatase on the path to ascorbate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16976–16981 (2004).

Laing, W. A., Wright, M. A., Cooney, J. & Bulley, S. M. The missing step of the L-galactose pathway of ascorbate biosynthesis in plants, an L-galactose guanyltransferase, increases leaf ascorbate content. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9534–9539 (2007).

Ledger, S. E., Janssen, B. J., Karunairetnam, S., Wang, T. & Snowden, K. C. Modified CAROTENOID CLEAVAGE DIOXYGENASE8 expression correlates with altered branching in kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). New Phytol. 188, 803–813 (2010).

Montefiori, M. et al. Identification and characterisation of F3GT1 and F3GGT1, two glycosyltransferases responsible for anthocyanin biosynthesis in red-fleshed kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). Plant J. 65, 106–118 (2011).

Park, Y. S. et al. Nutritional and pharmaceutical properties of bioactive compounds in organic and conventional growing kiwifruit. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 68, 57–64 (2013).

Pilkington, S. M., Montefiori, M., Jameson, P. E. & Allan, A. C. The control of chlorophyll levels in maturing kiwifruit. Planta 236, 1615–1628 (2012).

Torabinejad, J., Donahue, J. L., Gunesekera, B. N., Allen-Daniels, M. J. & Gillaspy, G. E. VTC4 is a bifunctional enzyme that affects myoinositol and ascorbate biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol. 150, 951–961 (2009).

Zuo, L. L., Wang, Z. Y., Fan, Z. L., Tian, S. Q. & Liu, J. R. Evaluation of antioxidant and antiproliferative properties of three Actinidia (Actinidia kolomikta, Actinidia arguta, Actinidia chinensis) extracts in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 5506–5518 (2012).

Ferguson, A. R. Kiwifruit: a botanical review. Hortic. Rev. 1–64 (1984).

Crowhurst, R. N. et al. Analysis of expressed sequence tags from Actinidia: applications of a cross species EST database for gene discovery in the areas of flavor, health, color and ripening. BMC Genomics 9, 351 (2008).

Testolin, R. et al. A kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.) linkage map based on microsatellites and integrated with AFLP markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103, 30 (2001).

Fraser, L. G. et al. A gene-rich linkage map in the dioecious species Actinidia chinensis (kiwifruit) reveals putative X/Y sex-determining chromosomes. BMC Genomics 10, 102 (2009).

The Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485, 635–641 (2012).

Xu, X. et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195 (2011).

Zhen, Y., Li, Z., Huang, H. & Wang, Y. Molecular characterization of kiwifruit (Actinidia) cultivars and selections using SSR markers. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 129, 374–382 (2004).

Hopping, M. E. Flow cytometric analysis of Actinidia species. N. Z. J. Bot. 32, 85–93 (1994).

Gnerre, S. et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1513–1518 (2011).

Sun, X. et al. SLAF-seq: An efficient method of large-scale de novo SNP discovery and genotyping using high-throughput sequencing. PLoS One 8, e58700 (2013).

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815 (2000).

Dassanayake, M. et al. The genome of the extremophile crucifer Thellungiella parvula. Nat. Genet. 43, 913–918 (2011).

Jurka, J. Repeats in genomic DNA: mining and meaning. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8, 333–337 (1998).

Ouyang, S. & Buell, C. R. The TIGR Plant Repeat Databases: a collective resource for the identification of repetitive sequences in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D360–D363 (2004).

Seal, A. G., Ferguson, A. R., De Silva, H. N. & Zhang, J. L. The effect of 2n gametes on sex ratios in Actinidia. Sex. Plant. Reprod. 25, 197–203 (2012).

Simillion, C., Vandepoele, K., Van Montagu, M. C., Zabeau, M. & Van de Peer, Y. The hidden duplication past of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13627–13632 (2002).

Shi, T., Huang, H. & Barker, M. S. Ancient genome duplications during the evolution of kiwifruit (Actinidia) and related Ericales. Ann. Bot. 106, 497–504 (2010).

Tang, H. et al. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Res. 18, 1944–1954 (2008).

Bulley, S. M. et al. Gene expression studies in kiwifruit and gene over-expression in Arabidopsis indicates that GDP-L-galactose guanyltransferase is a major control point of vitamin C biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 765–778 (2009).

Hedtke, B., Alawady, A., Chen, S., Bornke, F. & Grimm, B. HEMA RNAi silencing reveals a control mechanism of ALA biosynthesis on Mg chelatase and Fe chelatase. Plant Mol. Biol. 64, 733–742 (2007).

Kumar, A. M., Schaub, U., Söll, D. & Ujwal, M. L. Glutamyl-transfer RNA: at the crossroad between chlorophyll and protein biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 1, 371–376 (1996).

Jones, J. D. & Dangl, J. L. The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329 (2006).

Ming, R. et al. The draft genome of the transgenic tropical fruit tree papaya (Carica papaya Linnaeus). Nature 452, 991–996 (2008).

Guo, S. et al. The draft genome of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) and resequencing of 20 diverse accessions. Nat. Genet. 45, 51–58 (2013).

Meyers, B. C., Kozik, A., Griego, A., Kuang, H. & Michelmore, R. W. Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR-encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15, 809–834 (2003).

Goff, S. A. et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science 296, 92–100 (2002).

Jaillon, O. et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature 449, 463–467 (2007).

Li, R. et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272 (2010).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Zeitouni, B. et al. SVDetect: a tool to identify genomic structural variations from paired-end and mate-pair sequencing data. Bioinformatics 26, 1895–1896 (2010).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, (Suppl 1): i351–i358 (2005).

Edgar, R. C. & Myers, E. W. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics 21, (Suppl 1): i152–i158 (2005).

Trapnell, C., Pachter, L. & Salzberg, S. L. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 25, 1105–1111 (2009).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011).

Elsik, C. G. et al. Creating a honey bee consensus gene set. Genome Biol. 8, R13 (2007).

Burge, C. & Karlin, S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 268, 78–94 (1997).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995 (2004).

Kent, W. J. BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12, 656–664 (2002).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676 (2005).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997).

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J. Jr & Roos, D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189 (2003).

Zhang, Z. et al. KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 4, 259–263 (2006).

Tamura, K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Fan, X., Mattheis, J. P., Patterson, M. E. & Fellman, J. K. Changes in amylose and total starch content in ‘Fuji’ apples during maturation. Hort. Sc. 30, 104–105 (1995).

Gaudy, A. F. Colorimetric determination of protein and carbohydrate. Ind. Water Wastes 7, 17–22 (1962).

Karabegovic, I. T., Veljkovic, V. B. & Lazic, M. L. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of total phenols and flavonoids from dry tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves. Nat. Prod. Commun. 6, 1855–1856 (2011).

Chang, C., Yang, M., Wen, H. & Chern, J. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 10, 178–182 (2002).

Di Stefano, R., Cravero, M. C. & Gentilini, N. Metodi per lo studio dei polifenoli dei vini. L’Enotecnico I. Maggio 25, 83–89 (1989).

Otles, S. Comparative determination of ascorbic acid in bass (Morone lebrax) liver by HPLC and DNPH methods. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 46, 229–232 (1995).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Wellburn, A. R. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 11, 591–592 (1983).

Arnon, D. T. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 24, 1–15 (1949).

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Michael Wisniewski for his critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (nos. 2011CB100401 and 2012CB525003), National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31171179, 30770466, 90717110, 30970260, 30971752 and 31201597), Advanced Program of Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (no. 20110181130009), the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Distinguished Young Scientists (no. 30825030), the Key Project from the Government of Anhui Province (no. 2012AKKG0739), the Key Project from Chongqing Local Government (no. 2010AA1019), the Key Project from the Government of Sichuan Province (nos. 2013NZ0014, 2007FGY004, 2010NZ0052, 10010105 and 13ZC2279), the National Science and Technology Key Project of China on GMO Cultivation for New Varieties (nos. 2009ZX08001-011B and 2009ZX08009-072B), Young Scientist Foundation of Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences (no. 2011NKYJJ11) and the United States National Science Foundation (IOS-0923312).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H., J.D., D.D., W.T., Honghe Sun, D.L. and L. Zhang contributed equally to this work. S.H., J.D., W.T., Honghe Sun, L. Zhang, X.N., X. Zhang, M. Meng, J. Yu, W.S., D.Z., S.C., Z.W., Y.C., L. Lin., Y.M., H. Zhang, M. Miao, X.T., Y.Z., G.L., Hanju Sun, J. Sun, F.L., L. Zhou, L. Lei, J. Li, K.Y. and H.W. contributed to plant sample collection, DNA/RNA preparation, transcriptome sequencing and gene expression analyses; S.H., D.D., D.L., Y.X., H. Zeng, Y.Z., M.L., L.H., J. Song and C.X. worked on genomic DNA sequencing and genome assembly; L. Zhang, J. Liu, Y.H., Y.S. and X. Zheng contributed to genetic map construction, and assembly anchoring and orientation; S.H., J.D., D.D., W.T., D.L., Honghe Sun, K.B., S.Z., Y.X., H. Zeng Y.Z., J. Yue contributed to genome annotation, comparative genomic analyses and gene evolution; S.H., Honghe Sun, Z.F. and Y.L. contributed to website construction; Y.L., Z.F., H. Zheng, S.H., J.D., D.D., W.T., Honghe Sun, L. Zhang, X.N., Y.Z., J. Li, K.Y., S.Z., B.L., G.H., F.X. and H.W. wrote and revised the manuscript; Y.L., Z.F. and H. Zheng conceived strategies, designed experiments and managed projects. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S10 and Supplementary Tables S1-S15 (PDF 1512 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Transcription factors in the kiwifruit genome (XLSX 48 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

Transcriptional regulators in the kiwifruit genome (XLSX 16 kb)

Supplementary Data 3

NBS-LRR genes in kiwifruit (XLSX 13 kb)

Supplementary Data 4

RLK-PRR genes in kiwifruit (XLSX 21 kb)

Supplementary Data 5

Sequences of SNP (XLSX 482 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, S., Ding, J., Deng, D. et al. Draft genome of the kiwifruit Actinidia chinensis. Nat Commun 4, 2640 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3640

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3640

This article is cited by

-

Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated marker-free transformation and gene editing system revealed that AeCBL3 mediates the formation of calcium oxalate crystal in kiwifruit

Molecular Horticulture (2024)

-

Haplotype-resolved genome assembly provides insights into evolutionary history of the Actinidia arguta tetraploid

Molecular Horticulture (2024)

-

Genome of Argania spinosa L.: insights into oil production and the tocopherol biosynthesis pathway

Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (2024)

-

Telomere-to-telomere and haplotype-resolved genome of the kiwifruit Actinidia eriantha

Molecular Horticulture (2023)

-

Applications of CRISPR/Cas genome editing in economically important fruit crops: recent advances and future directions

Molecular Horticulture (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.