Abstract

There have been concerns about the effects of increases in maternal age since the 1980s on the prevalence of Down’s syndrome. This study examined changes in the distribution of maternal age in England and Wales from 1938 to 2010. The live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome in the absence of screening and subsequent termination was estimated using the numbers of babies born in England and Wales according to maternal age and the maternal age-related risk of a birth with Down’s syndrome. The proportion of women age 35 years or older at the time of giving birth reached a peak of 20% in 1945, declined to 5.5% in 1977 and rose to 20% in 2007. In the absence of screening and subsequent termination, the estimated live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome would have mirrored these changes (2.3 per 1000 births in 1945, 1.2 per 1000 in 1976 and 2.2 per 1000 in 2007). The observed live birth prevalence (recorded by the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register) was1.0 per 1000 from 1989 to 2010, due to screening and subsequent termination. In conclusion since the 1980s there has been an increase in the mean maternal age and in the expected prevalence of Down’s syndrome. When put in a longer historical context the current expected live birth prevalence is similar to that in the 1940s and the observed live birth prevalence is about 54% less than expected, due to screening and subsequent termination, and has remained reasonably constant since 1989 at 1.0 per 1000 births.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been considerable interest in couples deciding to delay having children for financial or career reasons, with concern about the effects of this on the prevalence of Down’s syndrome. However, the increases in maternal age have generally been compared only since the 1980s.1, 2 This paper aims to examine changes in maternal age and the associated live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome in England and Wales from 1938 to 2010.

Methods

The numbers of live births in England and Wales between 1938 and 2010 were extracted from Birth Statistics and Characteristics of Birth 2010, where they are stratified into 5-year maternal age groups.3, 4Maternal age is the strongest risk factor for Down’s syndrome and the maternal age-specific risk of having a baby with Down’s syndrome has been accurately estimated using the following equation: risk=1/(1+exp (7.330–4.211/(1+exp (−0.282 × (age −37.23))))).5, 6 The average age-specific risk was calculated for each age group (it was 0.66 per 1000 for under 20 years of age; 0.70 per 1000 for ages 20–24; 0.84 per 1000 for ages 25–29; 1.48 per 1000 for ages 30–34; 4.72 per 1000 for ages 35–39; 15.22 per 1000 for ages 40–44 and 30.71 per 1000 for 45 years and older). For each year of birth the number of live births with Down’s syndrome was estimated by multiplying these risks by the number of live births in that age group and summing across all age groups.

The number of babies born with Down’s syndrome has been reported annually since the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register (NDSCR) started to collect details of antenatal and postnatal diagnoses of Down’s syndrome in England and Wales in 1989,7, 8, 9 and such data were extracted from the 2010 NDSCR annual report.8

A χ2 test was used to examine differences in maternal age distribution at three different time points. Poison regression was conducted to investigate the trend of observed and expected live birth prevalence between 1989 and 2010.

Results

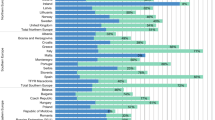

Figure 1 shows how the maternal age distribution has changed since 1940. The maternal age distribution was significantly different between 1940 and 1980 (P=0.0001) and between 1980 and 2010 (P<0.0001), but not different between 1940 and 2010 (P=0.46). In particular, the proportion of mothers who are aged under 25 increased dramatically to 1970 and then decreased to the level in 1940s.

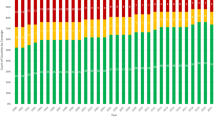

Figure 2 shows the proportion of mothers 35 years of age or older reached a peak of 19.7% in 1945, declined to 5.5% in 1977 before rising to a new peak of 20.4% in 2007. In the absence of prenatal diagnosis and subsequent terminations the estimated live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome mirrored these changes, with a peak of 2.27 per 1000 births in 1945 down to 1.22 per 1000 in 1976 and then up to 2.18 per 1000 in 2007.

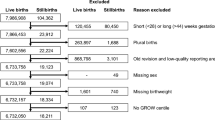

Figure 3 and Table 1 shows the estimated live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome in the absence of prenatal diagnosis and subsequent terminations compared with the observed live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome in England and Wales. The difference between the two curves was due to prenatal diagnosis and subsequent terminations being performed. Poisson regression for data between 1989 and 2010 shows an increase of 2.8% (95% CI: 2.6–3.0%) per annum in the estimated live birth prevalence, but only a very small annual increase of 0.3% (95% CI: 0.1–0.5%) in the observed live birth prevalence. The percentage reduction between the observed and expected live birth prevalence increased since 1989 (Table 1). In 2010, the observed live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome was 0.99 per 1000 births, 54% lower than expected due to prenatal diagnosis and subsequent terminations being performed.

Discussion

Figure 1 demonstrates that the recent proportions of older women having children are in fact similar to the proportions in the 1940s, even though the births to older mothers in the past would have been to women having large families, whereas the births now are likely to be either first or second children to mothers who have delayed having children. Birth order is not associated with the prevalence of Down’s syndrome, it is only the age of the mothers that is important.5, 6 Figure 2 shows how the prevalence of Down’s syndrome is predicted by maternal age. Although the use of infertility treatments using donated eggs is increasing, their use is still too infrequent to make a detectable change in the population prevalence of Down’s syndrome.

Other studies in Europe and the rest of the world have also observed increases in the proportion of mothers aged 35 and over since the 1980s.2, 10, 11, 12, 13 As the changes in the live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome are also dependant on the proportion of Down’s syndrome cases diagnosed prenatally and the proportion of subsequent terminations being performed, the birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome only increased slightly in the United States,11 stayed stable in Singapore and Europe,2, 12, 13 and decreased in Australia.10 In developing countries, such as China,14 with a lower availability of prenatal diagnosis and subsequent termination, the increase in the proportion of mothers aged 35 and over had a bigger impact on the birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome.

With the increasing availability of more powerful screening tests, such as the combined test, a higher proportion of Down’s syndrome fetuses are being detected prenatally particularly among younger mothers (the proportion of mothers under 35 with Down’s syndrome diagnosed prenatally increased from 10% to nearly 60% in England and Wales from 1989 to 2010, Figure 2 in NDSCR report8). The result of this increased detection rate and subsequent terminations in younger mothers has been to increase the maternal age of mothers with Down’s syndrome births from 30 to 35 years of age (Figure 4 in NDSCR report8). This 5 year increase is important when considering the implications for the long-term care of these children and subsequently adults with Down’s syndrome. The introduction of new techniques, such as sequencing fetal DNA in maternal blood,15, 16 would be expected to increase these trends in increasing detection rates. However, the birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome will continue to be highly influenced by any increases in maternal age and women should be made aware of these increased risks.

One of the weakness of this study is that before 1989 we do not know how many babies are born with Down’s syndrome. Data on the numbers of babies born with Down’s syndrome was collected by the National Congenital Anomaly Service (NCAS), and published annually by the Office for National Statistics from 1971 to 2008.17 However, both the NDSCR and other regional congenital anomaly registers demonstrated that the NCAS system had a significantly lower ascertainment rate.18, 19 Therefore, we have chosen not to use the data from NCAS for 1971–1989. The data on population births is only available in 5 year age bands, which will produce a small amount of inaccuracy.

In conclusion, this paper demonstrates that recent increases in maternal age mirror the decreases that occurred from the 1940s and that the live birth prevalence of babies with Down’s syndrome has remained reasonably constant since the introduction of prenatal diagnosis in the 1980s.

Change history

15 August 2013

This article has been corrected since online publication and a corrigendum is also printed in this issue.

References

Morris J, Alberman E : Trends in Down’s syndrome live births and antenatal diagnoses in England and Wales from 1989 to 2008: analysis of data from the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register. BMJ 2009; 339: b3794.

Loane M, Morris JK, Addor MC et al: Twenty-year trends in the prevalence of Down syndrome and other trisomies in Europe: impact of maternal age and prenatal screening. Eur J Hum Genet 2012; 21: 27–33.

Birth Statistics. England and Wales (Series FM1), No. 1-37.

Characteristics of Birth 2. England and Wales, 2010.

Cuckle HS, Wald NJ, Thompson SG : Estimating a woman's risk of having a pregnancy associated with Down's syndrome using her age and serum alpha-fetoprotein level. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1987; 94: 1225–1228.

Morris JK, Mutton D, Alberman E : Revised estimates of the maternal age specific live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome. J Med Screen 2002; 9: 2–6.

Mutton DE, Alberman E, Ide R, Bobrow M : Results of first year (1989) of a national register of Down’s syndrome in England and Wales. BMJ 1991; 303: 1295–1297.

Morris JK : The National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register for England and Wales 2010 Annual Report; Queen Mary, University of London, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry. 2011.

Morris JK, Alberman E : Trends in Down's syndrome live births and antenatal diagnoses in England and Wales from 1989 to 2008: analysis of data from the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register. BMJ 2009; 339: b3794.

Collins VR, Muggli EE, Riley M et al: Is Down syndrome a disappearing birth defect? J Pediatr 2008; 152: 20–24, 4 e1.

Shin M, Besser LM, Kucik JE et al: Prevalence of Down syndrome among children and adolescents in 10 regions of the United States. Pediatrics 2009; 124: 1565–1571.

Lai FM, Woo BH, Tan KH et al: Birth prevalence of Down syndrome in Singapore from 1993 to 1998. Singapore Med J 2002; 43: 070–076.

Irving C, Basu A, Richmond S et al: Twenty-year trends in prevalence and survival of Down syndrome. Eur J Human Genet 2008; 16: 1336–1340.

Bian XM, Guo Q, Qi QW : Current situation and development of prenatal diagnosis in China. Front Med China 2010; 4: 271–274.

Ehrich M, Deciu C, Zwiefelhofer T et al: Noninvasive detection of fetal trisomy 21 by sequencing of DNA in maternal blood: a study in a clinical setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204: 205 e1–11.

Chiu RW, Akolekar R, Zheng YW et al: Non-invasive prenatal assessment of trisomy 21 by multiplexed maternal plasma DNA sequencing: large scale validity study. BMJ 2011; 342: c7401.

Office for National Statistics: Congenital anomaly statistics notifications (Series MB3), No. 1-23.

Boyd PA, Armstrong B, Dolk H et al: Congenital anomaly surveillance in England--ascertainment deficiencies in the national system. BMJ 2005; 330: 27.

Savva GM, Morris JK : Ascertainment and accuracy of Down syndrome cases reported in congenital anomaly registers in England and Wales. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2009; 94: F23–F27.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sir Nicholas Wald at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine for his helpful comments. We thank Dr Gert de Graaf for his help with correcting this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Morris, J. Trends in maternal age distribution and the live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome in England and Wales: 1938–2010. Eur J Hum Genet 21, 943–947 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.288

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.288

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of autism spectrum disorder from 1990 to 2019 across 204 countries

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

The Potential Role of miRNAs as Predictive Biomarkers in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Journal of Molecular Neuroscience (2021)

-

Respiratory tract infection-related healthcare utilisation in children with Down’s syndrome

Infection (2020)

-

Older mothers and increased impact of prenatal screening: stable livebirth prevalence of trisomy 21 in the Netherlands for the period 2000–2013

European Journal of Human Genetics (2018)

-

Systematic Review of the Prevalence and Incidence of Intellectual Disabilities: Current Trends and Issues

Current Developmental Disorders Reports (2016)