Abstract

‘Evidence based medicine’ is a paradigm introduced in the 1990s in which collection of clinical data in a reproducible and unbiased way is intended to guide clinical decision-making. This paradigm has been promulgated across the spectrum of medicine, but with more limited critical analysis in the realm of pathology. The ‘evidence base’ in support of our practices in Anatomic Pathology is a critical issue, given the key role that such diagnoses play in patient management decisions. The question is, ‘On what basis are diagnostic opinions rendered in Anatomic Pathology?’ The operative question becomes, ‘What is the published literature that supports our anatomic pathology interpretations?’ This second question was applied to the published literature in Hepatopathology, by identifying the ‘citation classics’ of this discipline. Specifically, the top 150 most-cited liver pathology articles were analyzed for: authorship; journal of publication; type of publication; and year of publication. Results are as follows. First, it is indeed true that the preeminent hepatopathologists of the age are the most cited authors in the ‘top 150’. Second, the most cited articles in hepatopathology are not published in the pathology literature, but are instead published in much higher impact clinical journals. Third, the pathology of viral hepatitis is demonstrated to be extraordinarily well-grounded in ‘evidence based medicine’. Much of the remainder of the hepatopathology literature falls into a ‘narrative based’ paradigm, which is the rigorous reporting of case experience without statistical clinical outcomes validation. Finally, the years of publication reflect, on the one hand, a vigorous recent literature in the pharmaceutical treatment of viral hepatitis, and on the other, a broadly distributed set of ‘narrative’ articles from the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. In conclusion, the discipline of hepatopathology appears to be well-grounded in ‘evidence based medicine’ in the realm of viral hepatitis. The remainder of our discipline rests predominantly upon the time-honored identification of disease process through the publication of narrative case series.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

‘Evidence based medicine’ (EBM) is a term introduced in the early 1990s as a new paradigm for medical practice, whereby collection of clinical data in a reproducible and unbiased way is intended to guide clinical decision-making. To quote Sackett et al1 in their seminal 1996 publication, ‘the practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence’. The justification for EBM includes the need to cope with information overload (particularly when it is anecdotal), the need to contain costs, and the need to supply information to a public impatient for the best in diagnostics and treatment. The EBM paradigm is challenged by those who claim that it is unscientific, with instead a statistical and managerial approach to decision-making that undermines clinical expertise and clinical decision-making. EBM ostensibly requires large randomized controlled trials as the primary means of meeting rigid criteria on acceptable evidence, and hence connotates the demise of the expert opinion. ‘Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both…’. The critics note that when Frost pondered these two roads, he did not call for a randomized controlled trial.2

Evidence based medicine as a practice paradigm has had limited impact in the realm of Laboratory Medicine, over-and-above the use of laboratory values as read-outs for clinical trials. In the latter instance, Laboratory Medicine is bedrock data for determination of efficacy of pharmacologic therapies. Indeed, there is an implicit assumption that an evidence-based culture underpins the use of laboratory medicine. This is not necessarily a safe assumption.3, 4 The evidence base supporting use of specific test procedures or technologies may be quite limited, and in many cases flawed. Test utilization may expand well beyond the evidence supporting its initial implementation. Moreover, a key deficiency in the published literature is the absence of a statement of specific need for a laboratory test, namely, the clinical or operational question that the use of the test is seeking to answer. In the first instance, there is an ongoing need for Medical Directors of Clinical Laboratories to evaluate the impact of laboratory tests on clinical outcomes. This includes relevance of the test to clinical management decisions, role of timeliness of resulting (turnaround times), and the impact of test availability (or not). At the current time, analysis of such data has not kept pace with test implementation and utilization patterns in clinical medicine. Evidence-based strategies will be critical to the future development of Laboratory Medicine, especially with the profound appeal of new molecular tests.

The application of EBM to the practice of Surgical Pathology is an open question. One could argue that Surgical Pathology often operates in the realm of ‘Eminence based Medicine’, in which the professional stature of the Pathologist rendering the opinion constitutes the basis for justifying the diagnostic interpretation.5 For some, ‘clinical experience’ has been defined as ‘making the same mistakes with increasing confidence over an impressive number of years’.6 Perhaps, a less whimsical point of view is ‘Narrative-based Medicine’, whereby the art of selecting the most appropriate clinical decision is acquired largely through the accumulation of narrative ‘case expertise’.7 This is distinct from ‘evidence based medicine’, in which the clinical decision is informed first by statistical evidence, and only then is tempered by judgement acquired through clinical experience. A maxim of my own is, ‘You can gain a lifetime of experience with one case.’ To wit, the Pathologist placed in the center of a whirling maelstrom of an exceedingly difficult case has to: become thoroughly familiar with all aspects of the specific case (clinical history, physical examination, laboratory findings, radiographic findings, current response-to-therapies, current dilemmas); study the world's literature carefully; consult with local Pathologist colleagues and with experts around the world as needed; render an interpretation; and then educate the clinical team in both the nature of the disease and the implications of the pathology interpretation. This is not EBM; it is bringing the entirety of medical knowledge and experience to bear upon one case. This process occurs with remarkable regularity in the practice of surgical pathology.

The central role of the Pathologist in managing patient information was articulated by Sinard and Morrow8 in a 2001 editorial. In the broadest sense, the Pathologist should manage all patient information, including incorporation of local patient population outcomes into the validation (or not) of previous local clinical decisions. Our profession is, by nature, an information-management specialty. An information-based approach to Anatomic Pathology has been taken by Zarbo and co-workers, in which anatomic pathology databases have been analyzed to assess autopsy performance9 and quality of surgical pathology practice.10, 11, 12, 13

There are few other critical appraisals of the evidence base upon which diagnostic interpretations in Anatomic Pathology are rendered. Wright et al14 published the results of a 2001 Consensus Conference on Guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. Recognizing that assessment of cytological abnormalities of the uterine cervix for the amelioration and prevention of cervical cancer is one of the triumphs of 20th century medicine, these 121 experts reviewed the published literature supporting the use of existing interpretive guidelines of cervical cytopathology specimens. The resulting clinical management recommendations derive from an outstanding ‘evidence base’, which links cytopathology interpretations to validated clinical outcomes. Marchevsky and Wick15 provide an excellent review of the broader role of ‘evidence based medicine’ and ‘medical decision analysis’ (whereby mathematical tools are used to ‘reason with uncertainty’) in the practice of pathology. They note that pathologists will be well served by becoming more familiar with the basic concepts of EBM and how pathology data can be better integrated into formal medical decision analysis.

In this paper the question asked was, ‘What is the published literature that supports our interpretations of liver pathology?’ Textbooks were not used to answer this question, as these are compendiums written by experts on the basis of their experience and their knowledge of the literature. Rather, this question was addressed by identifying the ‘Citation Classics’ of our field. What can we learn from the most-cited (and presumably, most honored) publications in this discipline? Moreover, what are the distinguishing features of these articles?

Citation classics in hepatopathology

The top 150 citations in hepatopathology were obtained through a search performed using the Thomson Science Citation Index®, performed on 5 January 2006. Numerous terms pertaining to ‘liver’ and ‘pathology’, ‘hepatopathology’, ‘hepatic’ and ‘pathology’ were used, as were ‘histology’ and ‘histopathology’. Based on foreknowledge of critically important papers that were not identified through this mechanism, ‘hepatitis’ was searched without other qualifiers, as were ‘liver’ and ‘cancer’. Lastly, the membership of the original International Liver Pathology Study Group, the ‘Gnomes’16 was searched, owing to the fact that the field of hepatopathology was heavily influenced by the publications emanating from these individuals. Papers selected were those that specifically featured liver pathology on human material. The Appendix A presented on p XXX gives the top 50 ‘citation classics’; the full citations (1–150) can be obtained on the journal web site http://www.nature.com/labinvest/journal/v86/n4/full/3700343a.html.

While this search strategy may inevitably lead to omission of articles, the purpose of this exercise was to identify the apparent operative principles of published hepatopathology. Hence, omission even of prominent publications (however unintentional) through this search strategy should not invalidate the effort to identify general principles. In addition, because this search strategy did not include the experimental literature derived from animal work or in vitro studies, critical analysis was not performed of how laboratory experimentation has informed diagnostic interpretation of human liver biopsies.

Results

The top 150 citations in Hepatopathology—our ‘citation classics’—exhibited a range of citations per paper from 1921 down to 40. The publication years of cited papers were 1948 to 2002. Only the top 150 were examined, because there was an extreme ‘flattening of the curve’ below 40 citations per paper.

Authorship (Table 1)

Although the search strategy may be somewhat self-predicting, in point of fact the ‘Gnomes’ search turned up few articles that had not already been found by the topical search strategy. Hence, the first conclusion is that the publications that serve as the foundation for our subspecialty are contributed in a substantial fashion by those hepatopathologists whom we hold in the highest regard. Over the course of the 1940s to 1980s, this original generation of hepatopathologists shaped our subspecialty in a profound fashion, not only through their teachings but through publication of their experience from case material and writing about the implication of such diagnostic findings for clinical management.

One may also observe that a younger generation of hepatopathologists (now not-so-young) can be found among the ‘citation classics’. I am glad, however, that being a highly cited author is not a requirement for officership in the Hans Popper Hepatopathology Society (an official companion society of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology)!

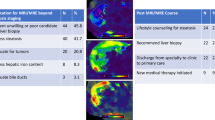

Journal of Publication (Tables 2a and b)

A very striking finding is that the best in the hepatopathology literature is published, not in pathology journals, but in major journals of clinical medicine: Hepatology, Gastroenterology, New Eng J Med, Lancet, J Hepatology. These data are given both for the top 50 cited articles (Table 2a), and the top 150 articles (Table 2b). It seems fair to say that hepatopathologists strive to have their best work published in the major clinical journals (especially Hepatology). This raises a critical dilemma: how do practicing rank-and-file pathologists gain access to the best publications in hepatopathology? To the extent that pathologists in the private sector do not have electronic journal subscription access to clinical journals, as would be true through an academic medical center, Hepatology and Gastroenterology, in particular, will not be available to them. What remains is for the super-subspecialists—the declared hepatopathologists who assiduously subscribe to the sub-specialty clinical journals—to educate the general pathology community through their extended efforts: presentations at national and regional meetings; lower impact articles published in the traditional surgical pathology journals. There is no easy answer to this question. This is, in fact, an issue for the breadth of academic pathology. For the first half of 2005, at least, fully half of ‘human pathology’ articles were published in clinical journals of higher Impact Factor than pathology journals.17 For many organ systems or tissues (especially liver, alimentary tract, and brain), the highest impact and most cited pathology articles are published in the respective clinical journals, not in the pathology literature. This raises the question of whether these publication practices by academic pathology properly foster the broader education of the practicing pathology community.

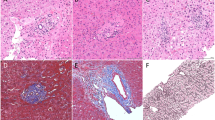

Publication Type (Table 3)

The crux of our discussion is whether the types of publication meet criteria for ‘Evidence based Medicine’. Table 3 gives a classification of publication types.

The first remarkable finding is that clinical studies of viral hepatitis that include histopathological information are the strongest group of ‘top 50’ hepatopathology citation classics. As will be discussed below, these articles are recent (within the past 10 years), and attest to a vigorous clinical literature addressing the clinical course and pharmacological treatment of chronic viral hepatitis (Citation Classics 2,3,5,9,10,11,13,16,27,33,37,41, 44,46,47). The fact that pathologists are frequent co-authors is both reassuring and essential. These articles represent, perhaps, the strongest case that can be made for hepatopathology truly having entered into the realm of ‘Evidence based Medicine’.

A second finding is that strictly pathology-oriented articles on chronic viral hepatitis, written by pathologists for pathologists, also are highly represented among ‘top 50’ citation classics. Chronologically starting with DeGroote et al in 1968 (7) and including revisions and re-revisions of the classification of viral hepatitis (Citation Classics 1,4,7,8,18,19,20,22,32,35,38), these articles are the bedrock upon which the aforementioned clinical studies are performed. An additional 20 of the articles in the ‘top 51–150’ also are in support of histopathological interpretation of chronic viral hepatitis (with one additional ‘viral hepatitis, clinical with pathology’ paper). I therefore conclude that it is the aggregate of these articles, 10 of the top 10, 26 out of the ‘top 50’, and 47 out of the ‘top 150’ that clearly demonstrate that hepatopathology is a well-established evidence-based subspecialty when it comes to viral hepatitis.

The emergence and reporting of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD, five articles in the ‘top 50’) and drug toxicities (two articles in the ‘top 50’) are important contributions by pathologists. The characterization of these important human conditions permits all practicing physicians to adapt their clinical management accordingly. A superb and rigorous literature has emerged for the recognition of hepatocellular carcinoma and its variants (three articles in the ‘top 50’), and interpretation of post-transplant liver biopsies (five articles in the ‘top 50’). These consist primarily of ‘narrative’ articles, either on the basis of case series (eg Citation Classics 15,23,42) or comprehensive consensus statements (eg Citation Classic 42). Declarations of consensus among clinicians and pathologists also have been a theme for autoimmune hepatitis (Citation Classics 14,29).

The reporting of extensive case series, and interpretation thereof by highly experienced pathologists, is perhaps the most-traveled form of surgical pathology scholarship. Over-and-above the case series mentioned above in the ‘top 50’ (Citation Classics 23,40,43), case series are very well-represented among the ‘top 51–150’ citation classics (57 out of 100 articles, not shown). On the one hand, these are the articles which every practicing hepatopathologist should know by heart, as they form the basis for interpretation of liver biopsies. On the other hand, these articles enable pathologists to serve as the ‘gold standard’ for evidence-based clinical studies, simply by declaring what disease process is actually occurring in the liver. Whether surgical pathology can truly serve as a ‘gold standard’, or is instead a ‘tin standard’ (since we are not obliged to correlate our interpretations with clinical follow-up in order to publish), is a topic beyond the scope of this review.

What remains to be determined is if reporting of case series, or deriving consensus among pathologists (or among clinicians and pathologists), has been adequately validated for each given disease category. There are occasional but important forays into this arena. In the top 150 hepatopathology citation classics, one article in particular stands out: a 1995 report by Demetris et al;18 (Citation Classic 137 out of 150, 46 citations) on the reliability and predictive value of a nomenclature and grading system for cellular rejection of liver allografts. The validation of a rigorous scoring system for assessment of cellular rejection in relation to its predictive value of clinical outcomes served as the foundation principle for subsequent interpretation of liver allograft biopsies.

Years of Publication (Table 4)

Final thoughts pertain to the years of publication for our citation classics. Over half of the top 50 articles were published in the decade 1996–2005 (to be exact, 1996–2002; 27/50). 1998 and 1999 were particularly strong years (6 and 5 ‘top 50’ publications, respectively), and almost all of these articles are clinical studies of viral hepatitis therapeutics that include histopathology data. These years are strong publication years for the outcomes of randomized clinical trials for interferon-alpha and ribavirin treatment of Hepatitis C viral infection.

The remarkable number of citations per article for ‘top 10’ articles (ranging from 1921 down to 762) may reflect in part the extraordinary facility for medical literature searches now made possible by electronic databases available worldwide. It may also reflect the fact that the older non-electronic literature, which cannot be down-loaded from electronic databases, is overlooked. It may simply be that there are more recent publications to cite. The exponential growth over the years of the medical literature has already been noted in a pair of somewhat whimsical letters-to-the-editor in the New England Journal of Medicine, whereby the pre-electronic Index Medicus volumes were weighed for each year and plotted as a function of their weight.19, 20 However, I ultimately believe that the high citation rates for the ‘top 10’ are a ‘true’ reflection of their medical importance, owing to the fact that they support clinical practice for a vast number of hepatitis patients worldwide.

Of particular note are two 1960s articles in the ‘top 50’. The 1968 Lancet article by DeGroote et al reporting ‘A classification of chronic hepatitis’ is 7th in the rankings (883 citations), and is the seminal article for rigorous histological evaluation of hepatitis. While this article did not link the pathology ‘interpretation’ to clinical outcomes, it declares that such a classification approach may be of value for future clinical work. This hope has certainly been realized. The 1967 Cancer article by Ishak and Glunz describes hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma in infancy and childhood. It is 23rd in the rankings, and has 337 citations. This is a superb example of utilizing case material in a ‘narrative’ fashion to map out the spectrum of human disease.

The remaining articles of the ‘top 50’ are well distributed through the 25 years spanning 1976–2001. These articles would truly qualify as the ‘classics’ of our subspecialty, as they address the key morphological findings pertinent for the diagnostic evaluation of chronic viral hepatitis, hepatocellular carcinoma and other liver neoplasms, liver transplantation, drug toxicity, and NAFLD.

The publication year frequencies of articles 51–150 are listed Table 4 as well; the extended bibliography may be accessed through the journal website. These articles represent the length-and-breadth of our subspecialty. There is a reassuringly broad spread of citation classics from the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. This finding supports the concept that steady effort on the part of pathologists worldwide has enabled the continued advance of our diagnostic and interpretive skills. Moreover, these articles continue to ‘live on’ in the published literature—a testament to their importance for our discipline.

The future of hepatopathology

It is too soon to know which articles published in 2001–2005 will become ‘citation classics’, and an attempt to make predictions would surely make strategic omissions. It is certainly reasonable to posit that a superb new generation of hepatopathologists will emerge, in part on the basis of the rigorous original work that they are currently performing. Articles published in 2005 that fall into an ‘evidence-based’ paradigm include studies of hepatocellular carcinoma staging21, 22 and treatment,23 and studies of the value of hepatic histologic findings in predicting the clinical outcomes of steatohepatitis24 and graft-versus-host disease.25 There is a healthy discussion of how to use the liver biopsy as a ‘gold standard’.26 Looking forward, there is eager anticipation of the publication of results for rigorous testing of histologic classification system(s) for NAFLD. The critical importance of molecular diagnostics in tissue pathology has been emphasized by ourselves17 and others. Genomic and proteomic characterization of human liver tissue is in progress,27, 28 and it will be critical to link these molecular data to clinical outcomes in order to fully realize the future value of liver tissue assessment. Taken collectively, there is every reason to expect that exceedingly important ‘evidence based’ articles will emerge in the 2001–2010 time frame.

Conclusion

This literature analysis reasonably establishes that hepatopathology, and pathologists interpreting liver biopsies, are well plugged in to efforts to use rigorous evidence to guide treatment of patients with liver disease. Both through stringent refinement of histologic classification systems, and rigorous utilization of these systems in randomized clinical controlled trials, the discipline of hepatopathology appears to stand on firm ‘evidence based’ ground. Second, the time-honored identification of disease process through the publication of case series constitutes the other foundation upon which we practice. Many of these case series are authored by the preeminent hepatopathologists of our age, thereby serving both the ‘eminence’ and ‘narrative’ strengths of medical knowledge. Certainly, there is room—and ongoing need—for high-quality publications from hepatopathologists worldwide. This is a necessity not only for the continued vitality of our discipline, but also for learning from case material worldwide. Third, our subspecialty should be well-suited for rigorous use of molecular techniques to assess liver disease and help drive clinical decision-making. Time will tell whether we take suitable advantage of this opportunity. Fourth, we should celebrate the worldwide community of hepatopathologists. This may be our greatest strength, in that we have opportunity to collaborate with one another, and work with our clinical colleagues worldwide. Lastly, I invite others to conduct similar analyses of their surgical pathology subspecialties, as an exercise in critically appraising the basis upon which we conduct our surgical pathology practices.

References

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J 1996;312:71–72.

Reilly BM . The essence of EBM: practising what we teach remains a big challenge. Br Med J 2004;329:991–992.

McQueen MJ . Overview of evidence-based medicine: challenges for evidence-based laboratory medicine. Clin Chem 2001;47:1536–1546.

Price C . Evidence-based laboratory medicine: supporting decision-making. Clin Chem 2000;46:1041–1050.

Isaacs D, Fitzgerald D . Seven alternatives to evidence-based medicine. Oncologist 2001;6:390–391.

O’Donnell M . A Sceptic's Medical Dictionary. BMJ Books: London, 1997.

Greenhalgh T . Narrative based medicine in an evidence-based world. Br Med J 1999;318:323–325.

Sinard JH, Morrow JS . Informatics and anatomic pathology: meeting challenges and charting the future. Hum Pathol 2001;32:143–148.

Baker PB, Zarbo RJ, Howanitz PJ . Quality assurance of autopsy face sheet reporting, final autopsy report turnaround time, and autopsy rates: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 10003 autopsies from 418 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996;120:1003–1008.

Zarbo RJ . Monitoring anatomic pathology practice through quality measures. Clin Lab Med 1999;19:713–742.

Zarbo RJ, Meier FA, Raab SS . Error detection in anatomic pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:1237–1245.

Raab SS, Grzybicki DM, Zarbo RJ, et al. Anatomic pathology databases and patient safety. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:1246–1251.

Raab SS, Grzybicki DM, Janosky JE, et al. Clinical impact and frequency of anatomic pathology errors in cancer diagnoses. Cancer 2005;104:2205–2213.

Wright Jr TC, Cox JT, Massad LS, et al. 2001 Consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. J Am Med Assoc 2002;287:2120–2129.

Marchevsky AM, Wick MR . Evidence-based medicine, medical decision analysis, and pathology. Hum Pathol 2004;35:1179–1188.

Reuben A . Where are the gnomes of yesteryear? Hepatology 2002;35:1554–1557.

Crawford JM, Tykocinski ML . Pathology as the enabler of human research. Lab Invest 2005;85:1058–1064.

Demetris AJ, Seabert EC, Batts KP, et al. Reliability and predictive value of the national institute of diabetes and digestive diseases and kidney diseases liver-transplantation database nomenclature and grading system for cellular rejection of liver allografts. Hepatology 1995;21:408–416.

Durack DT . The weight of medical knowledge. N Engl J Med 1978;298:773–775.

Madlon-Kay DJ . The weight of medical knowledge:still gaining. N Engl J Med 1989;321:908.

Varotti G, Ramacciato G, Ercolani G, et al. Comparison between the fifth and sixth editions of the AJCC/UICC TNM staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentric study on 393 cirrhotic resected patients. EJSO 2005;31:760–767.

Toyoda H, Kumada T, Kiriyama S, et al. Comparison of the usefulness of three staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma (CLIP, BCLC, and JIS) in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:1764–1771.

Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, et al. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transplant 2005;11:1086–1092.

Duarto RF, Delgado J, Shaw BE, et al. Histologic features of the liver biopsy predict the clinical outcome for patients with graft-versus-host disease of the liver. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11:805–813.

Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Qazi RA, et al. Effect of significant histologic steatosis or steatohepatitis on response to antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:604–609.

Kleiner DE . The liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C: a view from the other side of the microscope. Semin Liver Dis 2005;25:52–64.

van Dekken H, Verhoef C, Wink J, et al. Cell biological evaluation of liver cell carcinoma, dysplasia and adenoma by tissue micro-array analysis. Acta Histochemica 2005;107:161–171.

Parent R, Beretta L . Proteomics in the study of liver pathology. J Hepatol 2005;43:177–183.

Acknowledgements

This review is based, in part, upon a lecture and syllabus notes presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the Hans Popper Hepatopathology Society, as part of the meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology in Atlanta, February 2006. Thanks are given to Drs Chen Liu and Edward J Wilkinson for their critical reading of the manuscript, and to Dr Fred Silva for critical advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Laboratory Investigation website (http://www.nature.com/labinvest).

Supplementary information

Appendix A

Appendix A

Citation Classics in Hepatopathology, top 50 (as of 5 January 2006).

The full list of citations 1–150 is available on-line at http://www.nature.com/labinvest/journal/v86/n4/full/3700403a.html. The number in parentheses following the reference is the number of cites.

-

1

Knodell KG, Ishak KG, Black WC, et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1981;1:431–435. (1921)

-

2

McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. NEJM 1998;339:1485–1592. (1602)

-

3

Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, et al. Randomised trial of interferon alpha 2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha 2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. Lancet 1998;352:1426–1432. (1219)

-

4

Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, et al. Classification of chronic hepatitis—diagnosis, grading, and staging. Hepatology 1994;19:1513–1520. (1200)

-

5

Manns MP, McHutchinson JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Lancet 2001;358:958–965. (1047)

-

6

Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Lancet 908;1997;349:825–832. (908)

-

7

DeGroote J, Gedigk P, Popper H, et al. A classification of chronic hepatitis. Lancet 1968;2:626–629. (883)

-

8

Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1995;22:696–699. (782)

-

9

Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NWY, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. NEJM 1998;339:61–68. (768)

-

10

Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Rustgi V, et al. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. NEJM 1998;229:1493–1499. (762)

-

11

Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. NEJM 2002;347:975–982. (755)

-

12

Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. NEJM 1996;718;334:693–699. (718)

-

13

Poynard T, Leroy V, Cohard, M, et al. Meta-analysis of interferon randomized trials in the treatment of viral hepatitis C:Effects of dose and duration. Hepatology 1996;24:778–789. (522)

-

14

Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Alvarez, F, et al. Meeting report: International autoimmune-hepatitis group. Hepatology 1993;18:998–1005. (511)

-

15

Nalesnik MA, Jaffe R, Starzl TE, et al. The pathology of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders occurring in the setting of cyclosporine A–prednisone immunosuppression. Am J Pathol 1988;133:173–192. (510)

-

16

Nishiguchi S, S Kuroki T, Nakatani S, et al. Randomized trial of effects of interferon-alpha on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic active hepatitis-C with cirrhosis. Lancet 1995;346:1051–1055. (481)

-

17

Theise ND, Nimmakayalu M, Gardner R, et al. Liver from bone marrow in humans. Hepatology 2000;32:11–16. (442)

-

18

Dibisceglie AM, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, et al. Long-term clinical and histopathological follow-up of chronic posttransfusion hepatitis. Hepatology 1991;14:969–974. (440)

-

19

Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis—a need for reassessment. J Hepatol 1991;13:372–374. (422)

-

20

Scheuer PJ, Ashrafzadeh P, Sherlock S, et al. The pathology of hepatitis C. Hepatology 1992;15:567–571. (387)

-

21

Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1413–1419. (374)

-

22

Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1996;24:289–293. (352)

-

23

Ishak KG, Glunz PR. Hepatoblastoma and hepatocarcinoma in infancy and childhood—report of 47 cases. Cancer 1967:20:396–405. (337)

-

24

Mitchell JR, Zimmerman HJ, Ishak KG, et al. Isoniazid liver injury—clinical spectrum, pathology, and probable pathogenesis. Ann Int Med 1976;84:181–192. (303)

-

25

Bach N, Thung SN, Schaffner F. The histological features of chronic hepatitis C and autoimmune chronic hepatitis—a comparative analysis. Hepatology 1991;15:572–577. (302)

-

26

Nordlindger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver—A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Cancer 1996;77:1254–1262. (301)

-

27

Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL, Chaisson, RE, et al. Hepatotoxicity associated with antiretroviral therapy in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus and the role of hepatitis C or B virus infection. JAMA 2000;283:74–80. (297)

-

28

Tahara H, Nakanishi T, Kitamoto M, et al. Telomerase activity in human liver tissues—comparison between chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinomas. Cancer Research 1995;55:2734–2736. (286)

-

29

Alvarez E, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 1999;31:929–938. (285)

-

30

Lewis JH, Zimmerman HJ, Benson GD, et al. Hepatic injury associated with ketoconazole therapy—analysis of 33 cases. Gastroenterology 1984;86:503–513. (284)

-

31

Christensen E, Neuberger J, Crowe J, et al. Beneficial effect of azathioprine and prediction of prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis—final results of an international trial. Gastroenterology 1985;89:1084–1091. (282)

-

32

Yano M, Kumada H, Kage M, et al. The long-term pathological evolution of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1996;23:1334–1340. (281)

-

33

Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Di Martino V, et al. Liver fibrosis progression in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. Hepatology 1999;30:1054–1058. (279)

-

34

Wanless IR, Lentz JS. Fatty liver hepatitis (steatohepatitis) and obesity—an autopsy study with analysis of risk factors. Hepatology 1990;12:1106–1110. (267)

-

35

Berman M, Alter HJ, Ishak KG, et al. Chronic sequelae of non-A-hepatitis, non-B-hepatitis. Ann Int Med 1979;91:1–6. (263)

-

36

Angulo P, Keach JC, Batts KP, et al. Independent predictors of liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 1999;30:1356–1362. (258)

-

37

Marcellin P, Boyer N, Gervais A, et al. Long–term histologic improvement and loss of detectable intrahepatic HCV RNA in patients with chronic hepatitis C and sustained response to interferon-alpha therapy. Ann Int Med 1997;127:875–881. (246)

-

38

Lefkowitch JH, Schiff ER, Davis GL et al. Pathological diagnosis of chronic hepatitis-C—a multicenter comparative-study with chronic hepatitis-B. Gastroenterology 1993;104:595–603. (235)

-

39

Teli MR, James OFW, Burt AD, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver: a follow-up study. Hepatology 1995;22:1714–1719. (226)

-

40

Stromeyer FW, Ishak KG. Nodular transformation (nodular regenerative hyperplasia) of the liver—a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Hum Pathol 1981;12:60–71. (225)

-

41

Linsday KL, Trepo C, Heintges T, et al. A randomized double-blind trial comparing pegylated interferon alfa-2b to interferon alfa-2b as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2001;34:395–403. (223)

-

42

Demetris AJ, Batts KP, Dhillon AP, et al. Banff schema for grading liver allograft rejection: an international consensus document. Hepatology 1997;25:658–663. (223)

-

43

Demetris AJ, Lasky S, Vanthiel D, et al. Pathology of hepatic transplantation—a review of 62 adult allograft recipients immunosuppressed with a cyclosporine steroid regimen. Am J Pathol 1985;118:151–161. (222)

-

44

Hoofnagle JH, Shafritz DA, Popper H. Chronic type-B hepatitis and the healthy HBSAG carrier state. Hepatology 1987;7:758–763. (214)

-

45

Wanless IR, Mawdsley C, Adams R. On the pathogenesis of focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Hepatology 1985;5:1194–1200. (212)

-

46

Hourigan LF, MacDonald GA, Purdie D, et al. Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C correlates significantly with body mass index and steatosis. Hepatology 1999;29:1215–1219. (209)

-

47

Neiderau C, Lange S, Heintges T, et al. Prognosis of chronic hepatitis C: results of a large, prospective cohort study. Hepatology 1998;29:1687–1695. (201)

-

48

Rooks JB, Ory HW, Ishak KG, et al. Epidemiology of hepatocellular adenoma—role of oral contraceptive use. JAMA 1979:242:644–648. (199)

-

49

Anthony PP, Ishak KG, Nayak NC, et al. Morphology of cirrhosis. J Clin Pathol 1978:31:395–414. (197)

-

50

Charlton M, Seaberg E, Wiesner R, et al. Predictors of patient and graft survival following liver transplantation for hepatitis C. Hepatology 1998;28:823–830. (192)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crawford, J. Evidence-based interpretation of liver biopsies. Lab Invest 86, 326–334 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700403

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700403

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Original research in pathology: judgment, or evidence-based medicine?

Laboratory Investigation (2007)