Abstract

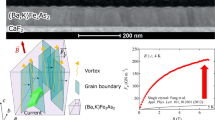

High temperature (high-Tc) superconductors like cuprates have superior critical current properties in magnetic fields over other superconductors. However, superconducting wires for high-field-magnet applications are still dominated by low-Tc Nb3Sn due probably to cost and processing issues. The recent discovery of a second class of high-Tc materials, Fe-based superconductors, may provide another option for high-field-magnet wires. In particular, AEFe2As2 (AE: Alkali earth elements, AE-122) is one of the best candidates for high-field-magnet applications because of its high upper critical field, Hc2, moderate Hc2 anisotropy, and intermediate Tc. Here we report on in-field transport properties of P-doped BaFe2As2 (Ba-122) thin films grown on technical substrates by pulsed laser deposition. The P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor exceeds a transport Jc of 105 A/cm2 at 15 T for main crystallographic directions of the applied field, which is favourable for practical applications. Our P-doped Ba-122 coated conductors show a superior in-field Jc over MgB2 and NbTi, and a comparable level to Nb3Sn above 20 T. By analysing the E − J curves for determining Jc, a non-Ohmic linear differential signature is observed at low field due to flux flow along the grain boundaries. However, grain boundaries work as flux pinning centres as demonstrated by the pinning force analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of Fe-based superconductors (FBS) by Kamihara et al.1, brought a huge impact to the physics community, since the compound consists of ferromagnetic Fe, which had been believed to be inevitably detrimental to the formation of Cooper pairs. To date, fundamental questions, such as mechanism of Cooper pairing and order parameter symmetry, are still under debate2. On the other hand, this material class is attractive for applications. For instance, AEFe2As2 (AE: Alkali earth elements, AE-122) and Fe(Se, Te) possess high upper critical fields (Hc2) exceeding 50 T and a low Hc2 anisotropy close to 1 at low temperature3,4, which is favourable for high-field-magnet applications. Furthermore, Ba-122 shows less deterioration of critical current across grain boundaries (GBs)5,6 than YBa2Cu3O7−δ (YBCO) and Bi-based cuprates. For Co-doped Ba-122, the critical GB misorientation angle (θc), where Jc starts to fall off exponentially, has been reported to be 6° − 9° 5,7. Even high angle GBs do not impede the current flow very much in sintered K-doped Ba-122 wires and bulks, if clean and well-connected GBs are realised8,9. Additionally, Co-doped Ba-122 exhibits a high tolerance for large densities of flux pinning centres in the superconducting matrix, which leads to significant increase in critical current density (Jc) and irreversibility field (Hirr)10.

Another advantage of Ba-122, in particular P-doped Ba-122, is its inherently high Jc. Putzke et al. have reported on the enhancement of the vortex core energy of the flux lines at the quantum critical point (QCP) of the antiferromagnetic phase11. Indeed, even microstructurally clean and optimally P-doped Ba-122 epitaxial thin films, which were prepared by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), exhibit a high self-field Jc of over 6 MA/cm2 at 4.2 K12. Although excess magnetic Fe has been found to be harmful to superconductivity in Fe(Se, Te)13, Fe-rich P-doped Ba-122 thin films showed a higher self-field Jc of over 10 MA/cm2 at 4.2 K, which is the highest value ever reported for FBS6. Whereas in the former case Fe is incorporated interstitially14, in the latter case the Fe may form Fe-containing particles or regions with differing P-content, both acting as pinning centres6. Furthermore, the high Jc and low anisotropy P-doped Ba-122 thin films can be fabricated by tuning the processing conditions only, without any modification of the target material used in pulsed laser deposition (PLD)15.

The aforementioned advantages of P-doped Ba-122 are very suitable for high-field-magnet applications. Indeed, P-doped Ba-122 thin films on technical substrates have been demonstrated as FBS coated conductors16,17. To date, two kinds of technical substrates have been employed for FBS coated conductors: The cube-textured metal tapes with buffer layers (i.e., RABiTS)18 and the Hastelloy tape on which biaxially textured buffer layers are prepared by ion-beam-assisted-deposition (IBAD)19.

In contrast to Fe(Se, Te) coated conductors20,21, transport properties of P-doped Ba-122 coated conductors in the presence of extremely high magnetic fields have not yet been reported. Here, we report on in-field transport properties of a P-doped Ba-122 thin film grown by PLD on metal substrate with biaxially textured MgO template (IBAD-MgO) in a wide range of temperature and DC magnetic field up to 35 T. We employ IBAD-MgO template with a relatively large in-plane full width at half maximum (FWHM) value (ΔϕMgO = 8°), since it has been demonstrated by x-ray diffraction (XRD) and transmission electron microscope (TEM) characterisations that the texture of MgO is transferred to the overlying P-doped Ba-122 film, generating dislocation networks17. Such dislocation networks enhance the vortex pinning in P-doped Ba-12217, since θc is less than 9° 5. Indeed, in-field Jc properties of our P-doped Ba-122 on IBAD-MgO with ΔϕMgO = 8° were superior to those of the film on a template with ΔϕMgO = 4° 17. A high density of threading dislocations is very effective for improving Jc for H||c in a wide range of temperature and magnetic field even close to Hirr. Despite the relatively large θc of 6°–9° for Ba-122, Jc of our P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor with sharp FWHM values of both in-plane, ΔϕBa−122 = 5.7°, and out-of-plane misorientaion, ΔωBa−122 = 1.2° (see Supplemental Fig. S1) is limited by the GBs in the low field regime. However, at high field, it exceeds a transport Jc of 105 A/cm2 at 15 T for field applied in both main crystallographic directions. Our P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor sample shows superior in-field Jc properties over MgB2 and NbTi, and a comparable level to Nb3Sn above 20 T.

Results

Resistivity measurements

The normal-state resistivity ρn (Fig. 1a) can be approximated by ρn = ρ0 + ATn with an exponent n-value of 1.28, ρ0 = 3.32 × 10−2 mΩ⋅cm and A = 8.22 × 10−5 mΩ⋅cm/K1.28 in the range of 30 < T < 150 K in accord with ref. 22. Shibauchi et al. have reported that the exponent n is unity at the quantum critical point (QCP) of the antiferromagnetic phase, where the maximum Tc is observed at 33% of P content for bulk single crystals23. Based on those results, we infer that the P content of our Ba-122 thin film on IBAD-MgO is different from the optimal level. Chemical analysis by electron probe microanalysis revealed a P content of 0.31, high enough to induce superconductivity with an onset Tc of 30 K for Ba-122 single crystal22. The lower Tc (28.3 K) of the P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor may be a consequence of epitaxial strain, since MgO single crystalline substrates induce in-plane tensile strain to Ba-122 films due to a large lattice mismatch24,25. The lattice parameters a and c of our P-doped Ba-122 coated conductors are located between the single crystals and thin films deposited on MgO single crystalline substrates (Fig. 1b). The crystalline quality of IBAD-MgO affects mainly ΔϕBa122 rather than ΔωBa12217, changing the amount of the in-plane strain and hence Tc.

(a) Temperature dependence of the resistivity measured in the absence of magnetic field. The dotted red line is a fit of the normal state resistivity curve in the range of 30 < T < 150 K using ρn = ρ0 + ATn. Inset: resistivity near the superconducting transition. The dotted blue line is a 90% reduction of the fitting curve (red dotted line). A Tc,90 of 28.3 K was recorded. (b) The relationship between lattice parameters a and c for P-doped Ba-122 single crystals22 and thin films on MgO single crystal substrates24 for various P contents. The highest-Tc values for single crystal and thin film are obtained by a P content of 33% and 23%, respectively. Lattice parameters a and c of our P-doped Ba-122 thin films on IBAD-MgO (two samples) are located between single crystals and thin films deposited on MgO single crystalline substrates. Both films have almost comparable ΔϕBa122 and ΔωBa122 values.

The linearity of the Arrhenius plots of ρ(T, H) for both major crystallographic directions at a certain magnetic field (Fig. 2a and b) reveals thermally activated flux motion under the assumption of a linear T-dependence of the activation energy, U0(H)26 (See the method section). It can be seen from Fig. 2c that U0(H) for both H||c and ||ab are well described by Hα(1 − H/H*)β above 10 T, which has been used for analysing polycrystalline MgB2 samples by Thompson et al.27 H* is a characteristic field representing the irreversibility field at 0 K27,28. The evaluated values for H||c and ||ab are 48.9 T and 59.7 T, respectively (for H||c and ||ab α = 0.68 and 0.64, and β = 1.1 and 0.94).

Arrhenius plots of the resistivity curves for (a) H||c and (b) H||ab. (c) Field dependence of the pinning potential for both main crystallographic directions. (d) Temperature dependence of the upper critical field for both major directions. (e) Temperature dependence of the irreversibility field for both major directions evaluated from ρ(T, H) and Jc(T, H) measurements. Zero temperature Hirr for H||c and ||ab evaluated from U0(H) is also shown.

A linear fit for lnρ(H) versus U0(H) using lnρ0(H) = lnρ0f + U0(H)/Tc, where ρ0f is the prefactor, yields Tc of 26.9 K for H||c and 27.2 K for H||ab, respectively (see Supplemental Fig. S2a). The Tc values evaluated by this method are slightly lower than the Tc,90 (see Fig. 1a). A plausible explanation for this difference is the increased transition width ΔTc due to the reduced texture quality compared to films on single crystal substrates or single crystal samples.

Hc2(T) was evaluated from the linear presentations of Fig. 2a and b (see Supplementary Fig. S2b and S2c) applying a ρn,0.9 = 0.9ρn resistivity criterion, where ρn,0.9 is the normal state resistivity ρn at 28.5 K. Shown in Fig. 2d is Hc2 for H||c and ||ab. The dotted line in Fig. 2d is the fitting curve using (1 − T/Tc)k. An exponent k of 0.9 was obtained for H||ab, which is far from the expected value of 0.5 for layered compounds limited by Pauli pair breaking at given T close to the dimensional crossover temperature29,30,31, which confirms that P-doped Ba-122 is a 3D superconductor. Because of the lack of low temperature data, it is not possible to fit the Hc2(T) (and Hc2(θ), shown later unambiguously) with a proper model for FBS32,33.

The temperature dependence of the irreversibility field, Hirr(T) (Fig. 2e) was evaluated from ρ(T, H) measurements using a resistivity criterion of ρc = Ec/Jc,100 = 1.0−8 Ω⋅cm, where Ec is the electric field criterion (1 mV/cm) for determining Jc from E − J measurements and Jc,100 is the criterion (100 A/cm2) for determining Hirr from Jc(H) measurements (see Supplementary Fig. S2d and S2e). The Hirr data at 0 K are estimated from the Arrhenius plots and they appear to match the low temperature limit of the Hirr data directly determined from the ρ(T, H) using the ρc criterion. For comparison, Hirr(T) determined from Jc(H) is also plotted in Fig. 2e showing some differences with the values estimated from ρ(T, H). A plausible reason is a different frequency of the applied current used in those investigations34.

The angular dependence of Hc2 at 20 K, which was derived from ρ(H) curves at constant angles with ρn,0.9 (Fig. 3a) shows a minimum at θ = 90° (H||c) and a maximum at θ = 180° (H||ab), as shown in Fig. 3b. The single-band anisotropic Ginzburg-Landau (AGL) theory35, Hc2(θ) = Hc2(90°)(sin2(θ) + cos2(θ)/γ2)−0.5 with γ = Hc2(180°)/Hc2(90°) (dotted line in Fig. 3b), cannot describe the measured Hc2(θ) due to the multi-band nature of this material, similarly to Co-doped Ba-12228. A fairly good description of the data is, however, achieved by the empirical formulae28,

with δ = 1.47 and γ = 1.62 (solid line). The parameter γ is the Hc2 anisotropy, whereas δ is a measure for the ab-peak width whose physical meaning is still unclear. These two values will be used later for scaling the angular dependence of Jc(θ) data.

The angular dependence of Hirr at 20 K derived using the same resistivity criterion ρc = 1.0−8 Ω⋅cm shows almost the same trend as Hc2(θ). Unlike the angular dependence of Jc (see next section), no clear peak at θ = 90° (H||c) is observed in Hirr(θ).

In-field critical current density Jc(T, H, θ)

The E − J curves of the P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor sample at 4.2 K (Fig. 4) show different behaviour at high and low magnetic fields for both major field directions. Up to 10 T they exhibit a non-Ohmic linear differential (NOLD) signature (i.e., E is linearly changing with J in linear scale, see Supplemental Fig. S3), indicative of Jc limitation by GBs36. Here NOLD behaviour is due to viscous flux flow along the GBs37. On the other hand, NOLD signature is almost absent above 12.5 T, suggesting that Jc is limited by intra-grain depinning of flux lines. This pinning crossover field is observed to decrease with increasing temperature (not shown), which is consistent with the cuprate YBCO reported in refs 38,39.

E − J curves for P-doped Ba-122 measured at 4.2 K for (a) H||c in the range of 0.5 < μ0H < 27.5 T and (b) for H||ab in the range of 0.5 < μ0H < 35 T. The electric field criterion of 1 μV/cm for evaluating Jc is also shown. A NOLD signature can be identified at low field by the deviation from the linear trend observed at high E.

Figure 5a compares Jc(H) for P-doped Ba-122 on IBAD-MgO for H||c at 4.2 K with P-doped Ba-122 on MgO single crystalline substrate15, Fe(Se, Te) on RABiTS21, YBCO coated conductor40, MgB241, NbTi42,43, and Nb3Sn44,45. Pinning-improved YBCO 2nd-generation (2G) tape shows the highest Jc at entire magnetic fields, however, a well textured template is necessary. The P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor exceeds a self-field Jc of 4 MA/cm2 and maintains a high Jc value of 50 kA/cm2 at 20 T. For the entire field range, Jc of P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor sample is larger than for MgB2 and NbTi. Above 20 T, the P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor sample shows comparable properties to Nb3Sn. Although lower-field Jc of P-doped Ba-122 on IBAD-MgO is higher than that of Fe(Se, Te) on RABiTS, the latter shows the better performance at medium and high fields. Figure 5b summarises Jc(H) for P-doped Ba-122 on IBAD-MgO for both crystallographic directions at various temperatures. At intermediate fields Jc for the two directions is comparable, indicative of the presence of correlated pinning along the c-axis.

(a) Jc − H properties of the P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor sample at 4.2 K for H||c in comparison to the data for P-doped Ba-122 on MgO single crystalline substrate15, Fe(Se, Te) on RABiTS21, YBCO coated conductor40, MgB241, NbTi42,43, and Nb3Sn44,45. (b) Jc − H properties of the P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor sample at various temperatures for both H||c (closed symbols) and H||ab (open symbols). Jc,100 is the criterion (100 A/cm2) used for determining Hirr. (c and d) The normalised pinning force fp as a function of reduced field h. The solid line is  for GB pinning, and the blue dotted line represent point-like pinning,

for GB pinning, and the blue dotted line represent point-like pinning,  .

.

By analysing the pinning force density Fp = μ0H × Jc, information on vortex pinning can be obtained. In general, the normalised pinning force, fp = Fp/Fp,max, is plotted as a function of reduced field h1 = H/Hirr at a given temperature for high-Tc superconductors. However, we plot fp as a function of h = H/Hmax, where Hmax is the field at which Fp shows the maximum46,47,48,49, since Jc could not be measured up to Hirr at all temperatures. As can be seen in Fig. 5c, the fp curves at different temperatures for H||c almost fall onto a master curve in the range of 0 < h < 3 described by

This formula is analogous to  (p = 0.5 and q = 2) found by Dew-Hughes50 for pinning by planar defects such as GB and twin boundaries, and by Kramer for line defect arrays51. In high-Tc superconductors with extremely short coherence lengths ξ, a further classification of the defect size with respect to ξ is necessary. It has been recently found by Paturi et al. that the exponent p is 0.5 irrespective of q for a defect size of the order of ξ and especially for dislocations in undoped YBCO films49. On the contrary, p increases towards 1 with increasing defect size. This confirms the finding that pinning in our sample is dominated by the dislocations with nano-size. Here, it should be noted that a sign of NOLD signature does not contradict GB pinning. In fact it has been reported for YBCO that the dislocations in GBs can work as vortex pinning centres52,53. The flux preferentially flows across the dislocation cores in the GB plane, which explains the E − J curves with a NOLD sign.

(p = 0.5 and q = 2) found by Dew-Hughes50 for pinning by planar defects such as GB and twin boundaries, and by Kramer for line defect arrays51. In high-Tc superconductors with extremely short coherence lengths ξ, a further classification of the defect size with respect to ξ is necessary. It has been recently found by Paturi et al. that the exponent p is 0.5 irrespective of q for a defect size of the order of ξ and especially for dislocations in undoped YBCO films49. On the contrary, p increases towards 1 with increasing defect size. This confirms the finding that pinning in our sample is dominated by the dislocations with nano-size. Here, it should be noted that a sign of NOLD signature does not contradict GB pinning. In fact it has been reported for YBCO that the dislocations in GBs can work as vortex pinning centres52,53. The flux preferentially flows across the dislocation cores in the GB plane, which explains the E − J curves with a NOLD sign.

Abrikosov-Josephson vortices (AJV) are present in low-angle GBs in both YBCO54 and FBS. Unlike Josephson vortices (JV), AJV have normal cores and can be trapped by flux pinning. Furthermore, the presence of an interaction between Abrikosov vortices (AV) in the grain and AJV at the GBs has been experimentally found in ref. 55: an increase in pinning potential for AV leads to the enhancement of the pinning potential for AJV.

For H||ab the fp curves at both 10 and 15 K follow well the GB pinning line (red solid line) up to 16 T (corresponding to h = 2 and 3.2 in Fig. 5d, respectively). In contrast, fp at 20 K neither follows the GB pinning nor point-like pinning (red solid and blue dashed lines, respectively) in high field regime, although the fp curve lies on the GB pinning line below h < 2. Similarly, the fp curve at 4.2 K follows the GB pinning curve up to h < 1.5 and then approaches the point-like pinning curve beyond h > 1.5. Hence, differently from the H||c case, the dominant pinning mechanism for H||ab is varying with temperature and field strength.

The angular dependence of the critical current density, Jc(θ) (Fig. 6a–d), shows two distinct peaks: a relatively sharp peak at H||ab and a broad maximum at H||c, which arises from the network of threading dislocations comprising the low-angle GBs17. Surprisingly, the c-axis peaks [Jc(90°)] remain visible even close to Hirr at all temperatures. Unlike single band superconductors, the anisotropy of coherence length, γξ = ξab/ξc, and penetration depth, γλ = λc/λab, of FBS exhibit opposite behaviour with temperature56. For an optimally doped Ba-122 system, γλ > γξ holds at all temperature. In this case even occasional uncorrelated defects slightly larger than ξ yield a strong c-axis pinning57. Such an effect in combination with threading dislocations along the c-axis may enhance enormously the average pinning potential for applied fields parallel to the c-axis.

Shown in Fig. 6e is the scaling behaviour of Jc(θ) as a function of the effective field [i.e.,  ] at 20 K. Here δ = 1.47 and γ = 1.62 were used as obtained by the Hc2(θ) fit. As can be seen, all Jc(θ) curves collapse onto a master curve in a wide angular range around H||ab. Differences between the master curve and the measured Jc(H) for H||c are correlated pinning contributions. Here we emphasise that the Jc peak at θ = 180° is fully determined by the electronic anisotropy at 20 K and no intrinsic pinning or pinning by planar defects is observed.

] at 20 K. Here δ = 1.47 and γ = 1.62 were used as obtained by the Hc2(θ) fit. As can be seen, all Jc(θ) curves collapse onto a master curve in a wide angular range around H||ab. Differences between the master curve and the measured Jc(H) for H||c are correlated pinning contributions. Here we emphasise that the Jc peak at θ = 180° is fully determined by the electronic anisotropy at 20 K and no intrinsic pinning or pinning by planar defects is observed.

Discussions and Conclusions

In order to realise FBS coated conductors, high Jc values with low anisotropy in high fields are necessary. Jc of our P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor nearly reached the practical level of ~0.1 MA/cm2 at 15 T for any applied field directions at 4.2 K [see Fig. 5a)], which shows superior properties over MgB2 and NbTi. Above 20 T the level of Jc is comparable to Nb3Sn. Additionally, the intrinsic anisotropy estimated at 20 K from the Hc2 data is below 2. Moreover the correlated defects increase Jc for H||c substantially suppressing the effective Jc anisotropy.

As stated above, the inequality of ξ and λ anisotropy in combination with a large density of threading dislocations along the c-axis significantly enhances the average pinning potential. It is worth mentioning that the population of threading dislocations can be controlled by the processing conditions only, without any modification of the PLD target15.

Compared to optimally P-doped Ba-122 films on MgO single crystal substrates by MBE12 and PLD15, the level of Jc of the P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor still needs to be improved. Film stoichiometry especially for P content should be controlled precisely. As stated before, the P content of our Ba-122 film slightly differs from the optimal level, where the QCP causes a sharp maximum for the vortex core energy11. As a consequence, the slight deviation from the optimal P level in our sample results in a lower vortex core energy, which directly reduces Jc.

Unlike in electron and hole doped Ba-122 systems, aliovalent disorder that contributes to pinning in the Co or K cases is absent in P-doped Ba-122. However, Jc can be further enhanced by introducing growth defects (e.g. intragrain dislocations since the PLD processing conditions strongly affect their density15) and artificial structures (e.g. nanoparticles). Moreover the thermal conductivity of single crystalline MgO is different from that of IBAD-MgO template, which infers the optimum deposition temperature may change.

The introduction of artificial pinning centres is effective for further improvement of Jc. In fact, Miura et al. have reported the introduction of BaZrO3 into P-doped Ba-122 matrix58 in analogy to the addition of BaZrO3 to YBCO. Hence, a combination of the introduction of artificial pinning centres and the precise control of P content will yield better performing P-doped Ba-122 coated conductors.

An attempt to fabricate a long length P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor has started quite recently. As a result, a 15 cm long P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor has been realised by PLD using a reel-to-reel system16. Albeit the resultant P-doped Ba-122 showed a small self-field Ic of 0.47 mA (corresponding to a Jc of 4.7 × 104 A/cm2) at 4.2 K, an improvement of Ic is foreseen by applying the aforementioned methods.

In summary, we have investigated in-field transport properties of a P-doped Ba-122 thin film grown by PLD on technical substrate in a wide range of temperature and DC magnetic field up to 35 T. The P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor exceeds a transport Jc of 105 A/cm2 at 15 T for both major crystallographic directions of the applied field. Additionally, the Jc peaks for H||c remain visible even close to Hirr at all temperatures by the enhanced vortex pinning due to the combination of large population of threading dislocations and the inequality of ξ and λ anisotropy. This leads to a lower Jc anisotropy. By analysing pinning force densities, we established that the GB pinning contribution is dominant for H||c, whereas for H||ab, the dominant pinning is varying with temperature. The results obtained through this study are considered promising for future high-field-magnet applications of AE-122 systems.

Methods

Growth of the P-doped Ba-122 film and structural characterisation

The P-doped Ba-122 thin film of 185 nm thickness was grown by pulsed laser deposition on an IBAD-MgO Hastelloy metal-tape substrate supplied by iBeam Materials, Inc59. The stacking structure of the IBAD-MgO substrate, as shown in ref. 17 consists of first a planarising bottom bed-layer amorphous Y2O3 on the Hastelloy, second a biaxially textured MgO layer formed by IBAD, and a top homoepitaxial MgO layer. The IBAD-MgO substrate with a large in-plane distribution angle of ΔϕMgO = 8° was investigated because higher Jc with isotropic properties can be achieved compared to the film on the well in-plane-aligned IBAD-MgO metal-tapes (i.e., ΔϕMgO = 4°)17. A polycrystalline BaFe2(As0.65P0.35)2 disk was used as the PLD target. We employed a higher growth temperature of 1200 °C than for optimised P-doped Ba-122 films on MgO single-crystal substrates (1050 °C)15, since the P concentration increases with increasing growth temperature for a given target composition. As expected, a higher P concentration closer to the optimum P concentration than in previous studies was achieved15,17. The other growth parameters [e.g., the excitation source and the laser fluence of the second harmonics (wavelength: 532 nm) of a Nd-doped yttrium-aluminum-garnet pulsed laser and 3 J/cm2, respectively] were the same as reported in ref. 15.

To determine the crystalline phases, ω-coupled 2θ scan X-ray diffraction measurements were performed. The asymmetric 103 diffraction of the P-doped Ba-122 film was measured to confirm the in-plane crystallographic four-fold symmetry without in-plane rotational domains. The crystallinity of the film was characterised on the basis of the full widths at half maximum (FWHMs) of the out-of-plane 004 (Δω) and the in-plane 200 rocking curves (Δϕ). The results of those XRD measurements can be found in Supplementary Information Fig. S1. The chemical composition was determined with an electron-probe microanalyser. The acceleration voltage of the electron beam was optimised while monitoring the Ni Kα spectrum to avoid the matrix effect from the Ni-containing Hastelloy metal-tapes.

In-plane transport measurements

A small bridge of 15 μm width and 500 μm length was patterned by photolithography, followed by ion-beam etching. Au electrodes with 50 nm thickness were formed by sputtering and lift-off. Transport properties using the resultant bridge were measured by a standard four-probe method.

The temperature dependence of the resistivity of the P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor shows a Tc,90 of 28.3 K (Fig. 1a), which is about 3 K lower than that of the optimally P-doped Ba-122 single crystals. Tc,90 is defined as the intersection between the steepest slope of the superconducting transition and a 90% reduction of the fit of the normal state resistivity using ρn = ρ0 + ATn. On the other hand, the onset Tc is defined as the intersection between the fit curve as stated above and the steepest slope of the superconducting transition. The difference between Tc,90 and the onset Tc is negligible.

The activation energy U0(H) for vortex motion was evaluated by the temperature dependence of the resistivity measurements in various field strengths up to DC 35 T at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Tallahassee, FL, USA. According to the model of thermally activated flux flow26, the slope of linear fit yields the pinning potential for vortex motion at given fields (Fig. 2c). On the assumption that U(T, H) = U0(H)(1 − T/Tc), both equations, lnρ(T, H) = lnρ0(H) − U0(H)/T and lnρ0(H) = lnρ0f + U0(H)/Tc, are obtained, where ρ0f is a prefactor.

In order to further understand the Hc2 anisotropy for a P-doped Ba-122 coated conductor sample, the angular dependence of the magnetoresistivity was measured at 20 K. Using the same constant criterion ρn,0.9 for evaluating Hc2, the angular dependent upper critical field [Hc2(θ)] was derived (Fig. 3b).

A criterion of 1 μV/cm was employed for evaluating Jc. In Jc measurement, the magnetic field was always applied in the maximum Lorentz force configuration. Low-field measurements were performed in a Quantum Design physical property measurement system (PPMS) in magnetic fields up to 16 T. For high field measurements up to DC 35 T, the experiments were conducted at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Tallahassee, FL, USA.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Iida, K. et al. High-field performance of a P-doped BaFe2As2 film on technical substrate. Sci. Rep. 7, 39951; doi: 10.1038/srep39951 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Kamihara, Y. et al. Iron-Based Layered Superconductor La[O1−x F x ]FeAs (x = 0.05–0.12) with T c = 26 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296–3297 (2008).

Hirschfeld, P. J. Using gap symmetry and structure to reveal the pairing mechanism in Fe-based superconductors. C.R. Physique 17, 197–231 (2016).

Yamamoto, A. et al. Small anisotropy, weak thermal fluctuations, and high field superconductivity in Co-doped iron pnictide Ba(Fe1−x Co x )2As2 . Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 062511 (2009).

Lei, H. et al. Pauli-limited upper critical field of Fe1+y Te1−x Se x . Phys. Rev. B 81, 094518 (2010).

Katase, T. et al. Advantageous grain boundaries in iron pnictide superconductors. Nat. Commun. 2, 409 (2011).

Sakagami, T. et al. Critical current density and grain boundary property of BaFe2(As,P)2 thin films. Physica C 494, 181–184 (2013).

Lee, S. et al. Weak-link behavior of grain boundaries in superconducting Ba(Fe1−x Co x )2As2 bicrystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 212505 (2009).

Weiss, J. D. et al. High intergrain critical current density in fine-grain (Ba0.6K0.4)Fe2As2 wires and bulks. Nat. Mater. 11, 682–685 (2012).

Weiss, J. D. et al. Demonstration of an iron-pnictide bulk superconducting magnet capable of trapping over 1 T. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 28, 112001 (2015).

Tarantini, C. et al. Development of very high J c in Ba(Fe1−x Co x )2As2 thin films grown on CaF2 . Sci. Rep. 4, 7305 (2014).

Putzke, C. et al. Anomalous critical fields in quantum critical superconductors. Nat. Commun. 5, 5679 (2014).

Kurth, F. et al. Unusually high critical current of clean P-doped BaFe2As2 single crystalline thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 072602 (2015).

Bendele, M. et al. Tuning the superconducting and magnetic properties of Fe y Se0.25Te0.75 by varying the iron content. Phys. Rev. B 82, 212504 (2010).

Sun, Y. et al. Dynamics and mechanism of oxygen annealing in Fe1+y Te0.6Se0.4 single crystal. Sci. Rep. 4, 4585 (2014).

Sato, H., Hiramatsu, H., Kamiya, T. & Hosono, H. High critical-current density with less anisotropy in BaFe2(As,P)2 epitaxial films: Effect of intentionally grown c-axis vortex-pinning centers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 182603 (2014).

Hosono, H. et al. Exploration of new superconductors and functional materials, and fabrication of superconducting tapes and wires of iron pnictides. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 16, 033503 (2015).

Sato, H., Hiramatsu, H., Kamiya, T. & Hosono, H. Enhanced critical-current in P-doped BaFe2As2 thin films on metal substrates arising from poorly aligned grain boundaries. Sci. Rep. 6, 36828 (2016).

Norton, D. P. et al. Epitaxial Yba2Cu3O7 on Biaxially Textured Nickel (001): An Approach to Superconducting Tapes with High Critical Current Density. Science 274, 755–757 (1996).

Iijima, Y. Tanabe, N., Kohno, O. & Ikeno, Y. In-plane aligned YBa2Cu3O7−x thin films deposited on polycrystalline metallic substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 60, 769–771 (1992).

Si, W. et al. Iron-chalcogenide FeSe0.5Te0.5 coated superconducting tapes for high field applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 262509 (2011).

Si, W. et al. High current superconductivity in FeSe0.5Te0.5-coated conductors at 30 tesla. Nat. Commun. 4, 1347 (2013).

Kasahara, S. et al. Evolution from non-Fermi- to Fermi-liquid transport via isovalent doping in BaFe2(As1−x P x )2 . Phys. Rev. B 81, 184519 (2010).

Shibauchi, T., Carrington, A. & Matsuda, Y. A Quantum Critical Point Lying Beneath the Superconducting Dome in Iron Pnictides. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 5, 113–135 (2014).

Kawaguchi, T. et al. The strain effect on the superconducting properties of BaFe2(As,P)2 thin films grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 27, 065005 (2014).

Iida, K. et al. Hall-plot of the phase diagram for Ba(Fe1−x Co x )2As2 . Sci. Rep. 6, 28390 (2016).

Palstra, T. T. M., Batlogg, B., Schneemeyer, L. F. & Waszczak, J. V. Thermally Activated Dissipation in Bi2.2Sr2Ca0.8Cu2O8+δ . Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 1662–1665 (1988).

Thompson, J. R. et al. Vortex pinning and slow creep in high-J c MgB2 thin films: a magnetic and transport study. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 18, 970–976 (2005).

Hänisch, J. et al. High field superconducting properties of Ba(Fe1−x Co x )2As2 thin films. Sci. Rep. 5, 17363 (2015).

Uher, C., Cohn, J. L. & Schuller, I. K. Upper critical field in anisotropic superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 34, 4906 (1986).

Klemm, R. A., Luther, A. & Beasley, M. R. Theory of the upper critical field in layered superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 12, 877–891 (1975).

Tarantini, C. et al. Significant enhancement of upper critical fields by doping and strain in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 84, 184522 (2011).

Gurevich, A. Upper critical field and the Fulde-Ferrel-Larkin-Ovchinnikov transition in multiband superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 184504 (2010).

Gurevich, A. Iron-based superconductors at high magnetic fields. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124501 (2011).

Pan, A. V., Golovchanskiy, I. A. & Fedoseev, S. A. Critical current density: Measurements vs. reality. EPL 103, 17006 (2013).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity. Dover Publication, New York 320 (2004).

Verebelyi, D. T. et al. Low angle grain boundary chemical fomula should be YBa2Cu3O7−δ coated conductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 1755–1757 (2000).

Díaz, A., Mechin, L., Berghuis, P. & Evetts, J. E. Observation of viscous flux flow in YBa2Cu3O7−δ low-angle grain boundaries. Phys. Rev. B 58, R2960–R2963 (1998).

Daniels, G. A., Gurevich, A. & Larbalestier, D. C. Improved strong magnetic field performance of low angle grain boundaries of calcium and oxygen overdoped YBa2Cu3O x . Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 3251–3253 (2000).

Fernández, L. et al. Influence of the grain boundary network on the critical current of YBa2Cu3O7 films grown on biaxially textured metallic substrates. Phys. Rev. B 67, 052503 (2003).

Xu, A. et al. Angular dependence of J c for YBCO coated conductors at low temperature and very high magnetic fields. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 23, 014003 (2010).

Li, G. Z. et al. Effects of carbon concentration and filament number on advanced internal Mg infiltration-processed MgB2 strands. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 26, 095007 (2013).

Boutboul, T. et al. Critical Current Density in Superconducting Nb-Ti Strands in the 100 mT to 11 T Applied Field Range. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 16, 1184–1187 (2006).

Kanithi, H. et al. Production Results of 11.75 Tesla Iseult/INUMAC MRI Conductor at Luvata. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 24, 6000504 (2014).

Parrell J. A. et al. High field Nb3Sn conductor development at Oxford Superconducting Technology. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 13, 3470–3473 (2003).

Parrell J. A., Field, M. B., Zhang, Y. & Hong, S. Nb3Sn Conductor Development for Fusion and Particle Accelerator Applications. AIP Conf. Proc. 711, 369 (2005).

Civale, L. et al. Scaling of the hysteretic magnetic behavior in YBa2Cu3O7 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 43, 13732–13735 (1991).

Qin, M. J. et al. Paramagnetism and scaling behavior of flux pinning force density in a GdBa2Cu3O6+x thin film. J. Appl. Phys. 78, 3287–3292 (1995).

Higuchi, T., Yoo, S. I. & Murakami, M. Comparative study of critical current densities and flux pinning among a flux-grown NdBa2Cu3O y single crystal, melt-textured Nd-Ba-Cu-O, and Y-Ba-Cu-O bulks. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1514–1527 (1999).

Paturi, P., Malmivirta, M., Palonen, H. & Huhtinen, H. Dopant Diameter Dependence of J c(B) in Doped YBCO Films. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 26, 8000705 (2016).

Dew-Hughes, D. Flux pinning mechanism in type II superconductors. Philos. Mag. 30, 293–305 (1974).

Kramer, E. J. Scaling laws for flux pinning in hard superconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 44, 1360–1370 (1973).

Díaz, A., Mechin, L., Berghuis, P. & Evetts, J. E. Evidence for Vortex Pinning by Dislocations in YBa2Cu3O7−δ Low-Angle Grain Boundaries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3855–3858 (1998).

Heinig, N. F., Redwing, R. D., Nordman, J. E. & Larbalestier, D. C. Strong to weak coupling transition in low misorientation angle thin film YBa2Cu3O7−x bicrystals. Phys. Rev. B 60, 1409–1417 (1999).

Gurevich, A. et al. Flux Flow of Abrikosov-Josephson Vortices along Grain Boundaries in High-Temperature Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 097001 (2002).

Palau, A. et al. Correlation between grain and grain-boundary critical current densities in ex situ coated conductors with variable YBa2Cu3O7−δ layer thickness. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 122502 (2006).

Kończykowski, M. et al. Anisotropy of the coherence length from critical currents in the stoichiometric superconductor LiFeAs. Phys. Rev. B 84, 180514 (2011).

van der Beek, C. J., Kończykowski, M. & Prozorov, R. Anisotropy of strong pinning in multi-band superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 25, 084010 (2012).

Miura, M. et al. Strongly enhanced flux pinning in one-step deposition of BaFe2(As0.66P0.33)2 superconductor films with uniformly dispersed BaZrO3 nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 4, 2499 (2013).

Sheehan, C. et al. Solution deposition planarization of long-length flexible substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 071907 (2011).

Acknowledgements

A portion of this work was performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which was supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1157490, and the State of Florida. The work at Tokyo Institute of Technology was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) through Element Strategy Initiative to Form Core Research Center. K.I. acknowledges support by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) Grant Number 16H04646. H.Hi was also supported by JSPS for Young Scientists (A) Grant Number 25709058, JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas Nano Informatics (Grant Number 25106007), and Support for Tokyotech Advanced Research (STAR). We acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Open Access Publishing Fund of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.I., C.T., J.H., H.S. and H.Hi. designed the study and wrote the manuscript together with J.J. and H.Ho. Thin films preparation, structural characterisations and micro bridge fabrications were carried out by H.S. and H.Hi. K.I., C.T., J.H. and J.J. conducted high field transport measurements. C.T., H.S. and H.Hi. performed low field transport measurements. K.I., C.T., H.Hi. and H.Ho. supervised the projects. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Iida, K., Sato, H., Tarantini, C. et al. High-field transport properties of a P-doped BaFe2As2 film on technical substrate. Sci Rep 7, 39951 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39951

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39951

This article is cited by

-

Approaching the ultimate superconducting properties of (Ba,K)Fe2As2 by naturally formed low-angle grain boundary networks

NPG Asia Materials (2021)

-

Particulate Generation on Surface of Iron Selenide Films by Air Exposure

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

. δ = 1.47 and γ = 1.62 evaluated from the Hc2(θ) were used. Blue solid line is the measured Jc − H for H||c at 20 K.

. δ = 1.47 and γ = 1.62 evaluated from the Hc2(θ) were used. Blue solid line is the measured Jc − H for H||c at 20 K.