Abstract

LmrR is a multidrug transcriptional repressor that controls the expression of a major multidrug transporter, LmrCD, in Lactococcus lactis. However, the molecular mechanism by which LmrR binds to structurally unrelated compounds and is released from the promoter region remains largely unknown. Here, we structurally and dynamically characterized LmrR in the apo, compound-bound and promoter-bound states. The compound-binding site of LmrR exhibits ps–μs dynamics in the apo state and compound ligation shifts the preexisting conformational equilibrium to varying extents to achieve multidrug recognition. Meanwhile, the compound binding induces redistribution of ps–ns dynamics to the allosteric sites, which entropically favors the high-affinity recognition. Furthermore, the reciprocal compound/promoter binding by LmrR is achieved by the incompatible conformational ensembles between the compound- and promoter-bound states. Collectively, the data show how LmrR can dynamically exert its functions through promiscuous multi-target interactions, in a manner that cannot be understood by a static structural view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The acquisition of multidrug resistance (MDR) by pathogenic bacteria is a major threat in the treatment of infectious diseases. Up-regulation of the expression of multidrug transporters that expel toxic compounds from cells is a strategy commonly employed by bacteria with MDR ability1,2,3. The expression of multidrug transporters is strictly regulated by transcriptional activators and/or repressors, which tend to have the ability to bind multiple toxic compounds4. In addition, the toxic compounds that are recognized by the multidrug transcriptional regulator and excreted by the transporters are often the same. Thus, drug excretion systems consisting of a set of multidrug transcriptional regulators and transporters efficiently upregulates the expression of the required multidrug transporters in response to toxic compounds. Similar systems are also well-documented in eukaryotes, especially in human cancers5,6.

A Gram-positive bacterium, Lactococcus lactis, exhibits MDR when exposed to increasing concentrations of structurally unrelated toxic compounds, such as Hoechst 33342 (H33342), daunomycin, ethidium and rhodamine 6G (Rho6G)7,8 (Fig. 1a). The MDR phenotype is induced by the overexpression of a heterodimeric multidrug transporter, LmrCD9. The expression of LmrCD is regulated by a multidrug transcriptional repressor, LmrR, which is encoded in the same gene cluster as the lmrCD gene10. LmrR is a homodimeric protein that belongs to the PadR-like family of multidrug transcriptional regulators4,11. In the absence of the compound, LmrR binds to the promoter regions of the lmrCD genes to repress their transcription (Fig. 1b). When the cells are exposed to the toxic compounds, LmrR is released from the promoter regions to induce membrane expression of the transporter12. LmrR has been shown to bind the aforementioned compounds with relatively high affinities13, thus, is a major sensory molecule that controls multidrug resistance in L. lactis.

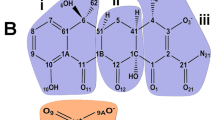

Substrate, regulatory mechanism and structural features of LmrR.

(a), Chemical structures of compounds that bind to LmrR. (b), Schematic representation of gene regulation by LmrR. (c), Ribbon diagrams of LmrR in complex with daunomycin. The compound (green sticks) binds to the pore at the dimeric center. (d), Different orientations of the C-terminal α4 helix relative to the wHTH motif. A superposition of the apo (cyan and light green), H33342-bound (blue) and daunomycin-bound (orange and red) LmrR subunit structures is shown. Inset: Close-up view of the hinge region. Ile-62 sidechain is shown as sticks while Ile-84 and Asn-88 are shown in surface representations.

The structures of LmrR in the apo state and in complexes with H33342 or daunomycin have been determined13. The LmrR dimer contains winged helix–turn–helix (wHTH) DNA-binding motif on the side of the molecule (Fig. 1c), which is thought to fit into successive DNA major grooves with the DNA-recognition helix, α3. The α4 helix, together with the α1 helix, forms a hydrophobic pore at the dimeric center to form the compound binding site. The compound binding has been proposed to change the orientation of the C-terminal α4 helix relative to the wHTH domain (Fig. 1d). In the apo and H33342-bound structures, the α4 helix is in an upper orientation. In contrast, the α4 helix lies more horizontally and adopts lower orientations in the daunomycin-bound structures. Thus, the common structural change upon the compound binding, which leads to the release of LmrR from the promoter regions, has not been identified. Nevertheless, since each of the three X-ray structures of LmrR are derived from different crystal forms, it is not possible to determine whether the different orientations are induced by compound binding or simply reflect differences in crystal packing13. The α4-helix orientations are correlated with the relative orientation between the DNA-binding α3 helices of LmrR. The distance between the α3 helices decreases with the lower α4-helix orientations than in the upper orientations13. However, none of the LmrR structures determined thus far is compatible with binding to B-form DNA. Therefore, the structural analysis of LmrR in the promoter-bound state as well as in the compound-bound states in solution, without any distortion caused by experimental conditions, is required, to reveal the molecular mechanism by which LmrR binds to various structurally unrelated compounds and is released from the promoter region to show the MDR phenotype.

Results

Dynamics of LmrR in the apo state

To characterize the dynamic nature of LmrR, we subjected the protein to solution NMR measurements. The backbone dynamics of apo LmrR were analyzed by the longitudinal and transverse 15N relaxation rates (R1 and R2, respectively), as well as the (1H)–15N heteronuclear nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs). The mainchain 15N relaxation analyses clearly indicated the existence of slow μs-ms chemical exchange at the compound-binding site, which is reflected in the large R2/R1 values observed for the residues in the α1 and α4 helices (Supplemental Fig.1a). Since the 15N R2 was insensitive in Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) experiments up to 1 kHz, the time scale of the dynamics in compound-binding site is much faster than the ms range. In addition, the low (1H)–15N heteronuclear NOE values indicated that part of the α4 helix exhibits substantial rapid internal dynamics on a ps–ns timescale (Supplemental Fig. 1b). Taken together, the compound-binding site of LmrR, especially the C-terminal α4 helix, displays intensive ps–μs dynamics in the apo state.

In the crystal structures of LmrR, a significant variation was observed in the α4 helix orientations, which might reflect its accessible conformational landscape (Fig. 1d). The differences in the α4-helix orientation are reflected in the different rotameric states of the residues in the hinge region that connects the N-terminus of the α4 helix to the wHTH domain. In particular, the χ2 angle of Ile-62 adopts the gauche– and trans rotameric states when the α4 helix is in the upper and lower orientations, respectively (Fig. 1d, inset). In the upper α4-helix orientations, Ile-62 χ2 is in the gauche– rotamer and the δ1 methyl moiety is accommodated in a small pocket, formed by Ile-84 and Asn-88 of the α4 helix. Conversely, in the lower orientations, the χ2 angle of Ile-62 is in the trans rotamer and the Ile-62 δ1 methyl moiety is rotated away from the α4 helix, due to the steric hindrance. Note that we assumed an exchange between not single, but multiple upper and lower orientations, based on the X-ray structures of LmrR (Fig. 1d), which demonstrated that upper and lower α4-helix orientations with different tilt angles exist for each rotameric state. Since the Ile χ2 angle is correlated with the 13C chemical shift of the δ1 position14, the 13C chemical shift and line shape of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance would reflect the population of the upper and lower α4-helix conformations at each state. In the 1H–13C HMQC spectrum of apo LmrR, the Ile-62 δ1 signal is broadened in the 13C dimension as compared to the others (Fig. 2a). According to the chemical shift value, the Ile-62 χ2 angle has a 1:1 population between the gauche– and trans rotamers in apo LmrR. Furthermore, the Ile-62 δ1 methyl showed a substantially low order parameter (S2; 0.17 ± 0.01, Fig. 2b), as compared to the others, except Ile-115 in C-terminal disordered region. These results indicated that the Ile-62 χ2 angle in the apo state undergoes rotameric exchange, reflecting an equally populated conformational equilibrium of the α4 helix among the upper and lower orientations.

Conformational equilibrium in apo LmrR.

(a), The Ile δ1 region of the 1H-13C HMQC spectra of LmrR in the apo state. (b), Methyl S2 values of Ile δ1. Error bars correspond to standard deviation (SD) of fitting errors. (c), Temperature dependence of the Ile δ1 resonances of apo LmrR. (d), The van 't Hoff plot for the Ile-62 χ2 angle rotational equilibrium in the apo state. The error bars correspond to the acquisition resolution of indirect 13C dimension. e, Temperature-dependent population change in Ile χ2, Leu χ2, Met χ3 and Val χ1 rotameric states between 281K and 303K. Right: the methyl moieties with more than 10% or 3% rotameric population shift in response to the temperature variation are highlighted in red and yellow, respectively. The methyl moieties that did not show more than 3% rotameric population shift were depicted by small blue spheres.

To further assess the conformational equilibrium observed in the apo state, we analyzed the temperature dependence of the methyl resonances from 281 K to 303 K. The 13C chemical shift of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance in the apo state was significantly shifted to high-field positions at lower temperatures (Fig. 2c). The 13C chemical shift difference between 281 K and 303 K was 0.78 ppm. This indicated that the population of the gauche– χ2 rotameric state of Ile-62 is increased from 50% to 65% by the temperature reduction from 303 K to 281 K, reflecting the preference for the upper α4-helix conformations at low temperature (Fig. 2d). As discussed above, Ile-62 χ2 in the upper α4-helix conformation adopted the gauche– rotamer and the δ1 methyl moiety of Ile-62 in the gauche– rotamer is accommodated in a small pocket, formed by Ile-84 and Asn-88 of the α4 helix, in the X-ray structure of LmrR (Fig. 1d). In agreement with this observation, the gauche– rotameric state is calculated to be −4.5 kcal mol−1 more enthalpically favorable than the trans rotameric state, according to the average slope of the van 't Hoff plot of the Ile-62 χ2 rotameric states (Fig. 2d). It should be noted that the fit of the van 't Hoff's equation appears be non-linear, although the non-linearity seems to be within the experimental errors derived from the acquisition resolution of the indirect 13C dimension. The non-linear characteristic might suggest that the heat capacity is changing within the temperature range tested. It should be noted that the dynamics of methyl groups are known to contribute to the heat capacity of a protein, through its local conformational entropy15. Fig. 2e shows the temperature-dependent changes in the rotameric populations of the Ile χ2, Leu χ2, Met χ3 and Val χ1 angles. The residues that exhibited substantial temperature-dependent population changes upon temperature reduction were distributed around the α4 helix, further supporting the presence of the conformational equilibrium of the α4 helix in the apo state of LmrR.

LmrR conformation in compound-bound state

To characterize the conformational changes associated with compound binding, four known compounds, H33342, daunomycin, ethidium and Rho6G, which have different sizes and shapes, were titrated to LmrR. SPR analyses indicated that these compounds bind to LmrR with various affinities, with dissociation constants (KD) values ranging from nM to μM (Supplemental Fig. 2a). The KD values for H33342 and daunomycin were consistent with those previously reported13. The chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) for each amide backbone resonance of LmrR revealed that LmrR engages the compounds with its compound-binding pore (Fig. 3). The amide CSPs induced by compound ligation were mostly converged in the middle of the compound binding site and thus they directly reflected the proximity of these amides to the compound in the bound states. Therefore, the amide CSPs would vary, depending on the chemical structures of the compounds and their respective binding modes. As expected from the X-ray crystal structures of LmrR, all compounds tested showed 1:1 binding stoichiometry.

CSPs of mainchain amide resonances of LmrR upon binding to compounds.

H33342, daunomycin, ethidium and Rho6G were added at the indicated concentrations. (a), Plot of the magnitudes of the normalized chemical shift change for each residue. The resonances that were only observable in the compound-bound states are indicated with asterisks. (b), Mapping of significantly perturbed (>0.05 ppm) residues on the ribbon representation of LmrR. Residues that were not observed in each bound state are shown in black.

Interestingly, the binding of different compounds induced similar CSPs to the Ile δ1 signals (Fig. 4a). In addition, the CSPs induced by the binding of H33342 to sites remote from the compound-binding interface, including those from the N- and C-termini of α1 and α4 helixes, correlated well with the CSPs induced by the binding of other compounds (Fig. 4b). Since the methyl groups of Ile δ1 as well as those depicted in Fig. 4b are all far away from the compound binding site and each chemical shift is a sensitive indicator of its local conformational and dynamical states14,16,17,18,19,20, the correlations between the CSPs from the remote sites shown in Fig. 4b reflect the common global conformational changes that are induced by compound ligation. The observation is a stark contrast to the X-ray structures of LmrR, which showed opposite structural changes upon binding to H33342 and daunomycin. As mentioned above, the orientations of the α4 helix are coupled to the Ile-62 13C chemical shift of the δ1 position14. Thus, the substantial high-field shift of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance in the 13C dimension, upon compound binding, indicates an elevated proportion of the upper orientations in the α4-helix conformational ensemble. The high-field Ile-62 δ1 13C chemical shift changes observed upon compound ligation correspond to 6–12% increase in the gauche– rotamer of the Ile-62 χ2 angle, which prefers upper α4 helix orientations. It should be noted that the position of the Ile-62 δ1 is always more than 4 Å away from the compound-binding site and thus its 13C chemical shift might not be directly affected by compound binding. It should be also noted that CSPs induced to amide resonances in Fig. 3 would vary, depending on the chemical structures of the compounds and their respective binding modes. In contrast, the Ile and remote methyl CSPs have to be comparable to those induced by the other compounds, as they reflect shared structural change.

Compound binding induces common conformational changes in LmrR.

(a), The Ile δ1 resonaces of LmrR in the apo state (black) was overlaid with that of the compound-bound states (red). The resonances with common CSPs are indicated with blue arrows. (b), The pairwise correlation between CSPs induced by daunomycin (left), ethidium (middle) and Rho6G (right) against CSPs induced by H33342, for each resonance that is more than 7 Å away from the compounds. The top and bottom panels are for 13C and 1H CSPs, respectively. All correlations showed p-values less than 0.001.

LmrR dynamics in compound bound-state

To determine the extent of variation of the α4-helix conformations in apo LmrR, as well as in the compound-bound states, we prepared 65 mutants of the residues in the α4 helix and those located at the interface with the α4 helix (Supplemental Fig. 3a). Each mutation introduced a perturbation of the conformational equilibrium of the α4 helix and the degree of perturbation was monitored by the 13C chemical shift of the Ile-62 δ1 resonances (Supplemental Fig. 3b). The 13C chemical shift changes in the Ile-62 δ1 resonance, as compared to wild type (WT) LmrR, upon the introduction of each mutation are shown in Fig. 5a. The maximum 13C chemical shift change was 0.85 ppm, which is comparable to that induced by temperature changes (Fig. 2c). Thus, the mutants sampled the conformational equilibrium that would reasonably be accessible for WT LmrR.

Conformational equilibrium of the α4 helix revealed by allosteric mutations.

(a), The 13C chemical shift change of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance in each mutant, relative to WT LmrR in the apo state. (b), The box and whisker plot of the 13C chemical shift of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance in various mutants in the apo state as well as in complexes with compounds. The red horizontal line indicates the 13C chemical shift of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance of WT LmrR in each state.

The 13C chemical shifts of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance in the various mutants in the apo form, as well as in the compound-bound forms, are shown in Fig. 5b. The Ile-62 δ1 resonance showed a wide distribution of 13C chemical shifts, ranging from 11–12.5 ppm, reflecting the shallow energetic potential landscape and the significant variety in the preexisting conformational states in apo LmrR. Upon compound binding, the distribution of the 13C chemical shifts of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance was shifted to high-field (i.e. low-frequency) positions to a different extent for each compound and the range of the chemical shift variations became smaller. Interestingly, the chemical shift variation observed in the apo state includes a substantial part of chemical shift distribution observed in the compound-bound states. This indicated that compound ligation increases the populations of the upper α4-helix conformations, among the preexisting conformational ensembles in the apo state.

Nevertheless, the substantial temperature dependence revealed by the van't Hoff plot remained in all of the compound-bound states, indicating that the conformational equilibrium of the α4 helix is not fully suppressed in the compound-bound states (Supplemental Fig. 4). Note that the bound-state spectra of LmrR were recorded with at least a 40-fold excess concentration of the compound, as compared to the KD values and most of the mutants retained a reasonable binding affinity toward the compounds. Thus, the chemical shift distribution and the temperature dependence are those of the compound-bound states. These results indicated that LmrR recognizes the various structurally unrelated compounds by shifting the equilibrium among the preexisting conformational ensembles in the apo state. This notion is further supported by the fact that the mutants that showed extreme populations in the conformational equilibrium exhibited lower affinities toward the compounds (Supplemental Fig. 3c–f).

To understand the thermodynamic nature of the LmrR-compound interaction, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) analyses were performed. Within the binding free energy of the LmrR-compound interactions, the enthalpic contributions, which reflect the formation of spatially aligned interactions, are small or even unfavorable (Supplemental Fig. 2b and c). While the major entropic term favoring association would be the desolvation from the hydrophobic compound-binding pore of LmrR, changes in the protein conformational entropy would also account for the ligand binding affinity21. To determine the contribution of the protein conformational entropy to the LmrR-compound binding, we employed 1H spin-based relaxation violated triple-quantum (3Q) coherence transfer NMR spectroscopies, to measure the changes in S2 (ΔS2) of the methyl groups upon compound binding22,23. Since S2 is a measure of the amplitude of internal dynamics, it is related to the conformational entropy24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Compound binding to LmrR resulted in a notable increase in the amplitude of ps–ns dynamics throughout the entire protein, except for a few methyl moieties in the compound binding site (Fig. 6). The residues that showed increased ps–ns dynamics are concentrated at the interface between the compound-binding and DNA-binding domains (upper left and lower right corner in the structures shown in Fig. 6), which is allosteric to the compound-binding site and exhibited small amplitude of ps–ns dynamics in the apo state (Supplemental Fig. 5). Thus, the compound binding induces the redistribution of the ps–ns dynamics in LmrR, thereby favorably contributing to the binding by increasing the conformational entropy.

Enhancement of ps–ns motions in allosteric sites upon compound binding.

Left panels show ΔS2 values for each methyl resonance upon binding to (a), H33342, (b), daunomycin, (c), ethidium and (d), Rho6G. The right panel displays the color-coded mapping of the methyl moieties that showed substantial ΔS2 values upon binding to each compound. Error bars correspond to SD of fitting errors.

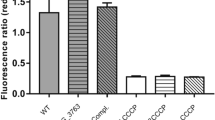

Reciprocal compound/promoter binding

LmrR shows reciprocal compound- and promoter-DNA-binding properties. To gain structural insights into the reciprocal interactions, we subjected the LmrR–promoter complex to SPR and solution NMR studies. It has been suggested that LmrR interacts with the promoter/operator region of the lmrCD gene, including an imperfect inverted repeat (IR) with a PadR consensus. Thus, we used the 33-bp promoter DNA fragment, containing the IR sequence, for the analyses (Supplemental Fig. 6a; hereafter, we refer to this as the lmrCD oligo). The SPR analyses indicated that the lmrCD oligo showed μM affinity for LmrR (Supplemental Fig. 6b) and was dissociated from LmrR in the presence of the compounds (Supplemental Fig. 6c). Titration of the lmrCD oligo to LmrR induced a low-field shift in the Ile-62 δ1 13C chemical shift, which indicated that the conformational equilibrium of the α4 helix was shifted to have higher proportion of the lower orientations (Fig. 7a). In addition, the Ile δ1 CSPs induced by the lmrCD oligo were anti-correlated with those induced by the compounds (Fig. 7b). Thus, the compounds and the promoter DNA prefer distinct α4-helix conformational ensembles present in LmrR and provide the structural basis for the reciprocal binding.

NMR analyses of binding of promoter DNA oligo to LmrR.

(a), The Ile δ1 region of the 1H-13C HMQC spectrum of LmrR in the apo state (black) was overlaid with that of the lmrCD oligo-bound state (red) (b), The pairwise correlation between CSPs induced by daunomycin (left) and ethidium (right) against CSPs induced by the lmrCD oligo for each Ile δ1 resonance.

Discussion

Our structural and dynamical analyses of LmrR in the apo state revealed intensive ps–μs dynamics in the compound-binding site. LmrR adopts multiple α4 helix orientations, which are largely classified into the upper and lower conformations and each of these conformations should have certain variations in their tilt angles (Fig. 1d). The upper and lower conformations are associated with gauche– and trans rotamers in Ile-62 χ2 angle, respectively. As discussed above, the gauche– rotamer is enthalpically preferred in the upper α4-helix orientations, as it has additional contact between Ile-62 δ1 methyl and the α4 helix. The smallest 13C chemical shift value of the Ile-62 δ1 methyl moiety for the H33342 complexes corresponds to 74% of rotameric state in the gauche– rotamer (Fig. 5b). Thus, the Ile-62 χ2 angle would, at least in its majority, be in the gauche- rotamer when α4-helix is in upper orientations. On the other hand, the lower orientation forces the Ile-62 χ2 angle to take trans rotamer due to steric hindrance. Thus, the average population and rate of exchange between the upper and lower conformations are reflected in the 13C chemical shift and line shape of the Ile-62 δ1 resonance. In the apo state, the upper and lower conformations are almost equally distributed, indicating that those conformers on average are energetically degenerate (Figs. 2d and 8a; top). Theoretically, an energetically degenerate system is the most sensitive to a perturbation that shifts the conformational equilibrium36. Thus, apo LmrR appears to be optimally suited for sensing and responding to a variety of compounds, by shifting the conformational ensembles to those that differ from apo LmrR. There should be a small but appreciable barrier between the upper and lower α4 helix conformations, judging from a broader 13C line width in the Ile-62 δ1 signal (Fig. 2a), which would not be observed if no activation barrier existed between conformations. Considering the facts that 15N R2 was insensitive in CPMG experiments up to 1 kHz and that the Ile-62 δ1 gives a single line of resonance, the exchange rate between the conformations should be faster than 103 s−1 and the apparent activation energy would be smaller than 13 kcal mol−1, according to the Arrhenius equation.

Multidrug recognition and transcriptional regulation through differential shifting of the preexisting conformational equilibrium.

(a), In the apo state, LmrR exists as a conformational ensemble with multiple α4-helix orientations, in which the upper and lower conformations are almost equally represented (top). Compound ligation shifts the preexisting conformational equilibrium to various extents, to achieve multidrug recognition (middle). The reciprocal compound/promoter binding by LmrR is achieved by the incompatibility of the conformational ensembles (lower). (b), Comparison of the multidrug recognition by LmrR (left) with that by QacR (right). LmrR binds to multiple compounds using the same site without being locked into a specific conformer. In contrast, QacR possesses multiple specific binding spots in a wide binding pocket to recognize multiple compounds using different sites.

The compound binding shifts the conformational ensemble of the α4 helix observed in apo LmrR to a higher proportion of the upper conformers, but to a different extent for each compound (Figs. 5b and 8a; middle). Thus, there are common structural changes, which have not been identified by the former structural study of LmrR. The multidrug recognition mechanism is somewhat similar to the multi-protein recognition by ubiquitin via a conformational selection mechanism37, in which the bound conformations of ubiquitin are already present in the free state. However, in stark contrast to the multi-protein recognition by ubiquitin, LmrR possesses only one compound-binding pore, whereas ubiquitin has distinct binding sites on the molecule for different interaction partners. The ps–μs dynamics in the LmrR compound-binding site is not fully suppressed upon compound binding (Fig. 5b and Supplemental Fig. 4) and only limited numbers of the methyl moieties in the compound-binding site showed reduced ps–ns dynamics upon compound binding (Fig. 6). Thus, the loss of protein conformational entropy at the binding interface, which typically accompanies complex formation21, was limited in the LmrR-compound interactions.

Interestingly, the compound binding enhanced the ps–ns dynamics in the sites that are allosteric to the compound-binding interface (Fig. 6). The redistribution of the ps–ns dynamics would entropically favor the interactions between LmrR and the compounds. Although the major favorable entropic term associated with the compound binding arises from the desolvation effect, the redistribution of the fast internal dynamics in the allosteric sites would also positively contribute to the compound interaction. From the recently proposed relationship between measured methyl-group S2 and conformational entropy38, −0.5 to −1.5 kcal/mol of entropic energy gain were expected upon compound binding, which increases the binding affinity by 2- to 13-fold. Since LmrR is a sensory molecule that detects various toxic compounds, the high affinities toward the compounds are prerequisite to its function. In this sense, LmrR represents an elaborate system that is compatible with both high-affinity binding and multidrug recognition, via the redistribution of the ps−ns motions upon compound ligation.

In Fig. 8b, we show a schematic representation of the compound recognition by LmrR, compared to that of the TetR-family multidrug transcriptional repressors. The NMR analysis revealed that LmrR recognizes various structurally unrelated compounds by shifting the equilibrium among the conformational ensembles presented in the apo form (Fig. 8a and b; left). This recognition mode is quite different from the multidrug recognition by the TetR-family multidrug transcriptional repressors, which utilize multiple specific binding spots in a wide binding pocket to recognize multiple compounds (Fig. 8b; right). The difference is reflected in the thermodynamics of the compound recognition. While the binding of the compounds to LmrR is entropically favored, the compound binding to a TetR-family member, QacR, is enthalpically favored and entropically disfavored, which clearly indicate the specific bond formations that potentially limit the structure of the compound that can be accommodated by QacR39. We should emphasize that the multidrug recognition mechanisms of QacR, as with other mechanisms proposed for other families of multidrug transcriptional regulators, rely on the specific protein-drug interactions and thus the number of the compounds accommodated by the mechanisms is limited. However, the multidrug recognition through a dynamic shift of conformational equilibrium does not rely on prerequisite bond formations and thus, in principle, is able to accommodate almost unlimited number of compounds with planar aromatic structures that can fit into the single drug binding pore and represents a multidrug binding mechanism, which does not fall into any category proposed thus far.

Lastly, the distinct conformational ensembles preferred by the promoter DNA and the compounds (Figs. 7 and 8a), which we found here, are fundamental to the reciprocal compound/promoter binding by LmrR. This would occur via structural coupling between the α4-helix orientation and the distance between the α3 DNA-recognition helices. The compound binding increases the upper conformations of the α4 helix, causing an increase in the average distance between the α3 helices. In contrast, binding to the promoter DNA oligo induces the lower conformations of the α4 helix and thus the shorter distance between the α3 helices would be expected. In the absence of the promoter-bound structure of LmrR, we cannot rule out the possibility of DNA distortion; however, the perturbation of the LmrR conformational ensemble upon binding to the promoter DNA is evident from the promoter-induced CSPs. Ile-62 is located in the hinge region of the α4 helix and it is reasonable that Ile-62 showed a substantial 13C CSP. In addition, Ile-57, which is located in the α3 DNA binding helix and interacts directly with the Ile-62 sidechain, also changed its rotameric state from gauche– to trans when the conformation of the α4 helixes was shifted from lower to upper. Considering the location of Ile-57 and its correlation to the conformation of the α4 helix, Ile-57, along with Ile-62, would form the structural core to transfer the α4 conformation to α3 DNA binding helix, which serves as a conformation switch that induces LmrR dissociation from the promoter upon compound ligation.

Methods

Preparation of LmrR

The DNA fragment (5′-GGCCATGGGCATGGCCGAAATTCCGAAAGAGATGCTTCGTGCTCAGACCAATGTGATTCTGCTGAATGTCCTGAAACAGGGTGATAACTACGTATATGGCATTATCAAACAGGTGAAAGAAGCGAGTAATGGCGAAATGGAACTGAACGAAGCAACTCTCTACACCATCTTCAAACGCCTGGAGAAAGATGGGATCATTAGCAGCTATTGGGGTGATGAATCTCAAGGTGGACGTCGCAAGTACTATCGCTTGACGGAAATTGGCCATGAGAACATGCGGTTAGCCTTTGAATCGTGGTCACGTGTTGACAAGATCATTGAGAATCTGGAAGCGAACAAGAAATCCGAAGCGATCAAACTCGAGTGA-3′) encoding L. lactis LmrR, with optimized codon usage for Escherichia coli (E. coli) protein expression, was synthesized (Operon) and ligated into a pET28b vector (Novagen) at the Nco I and Xho I restriction sites. The resultant vector expresses LmrR with a C-terminal His6-tag. LmrR mutants were constructed by the QuikChangeTM strategy (Agilent Technology). E. coli strain BL21(DE3) was transformed with the plasmid. Fresh colonies of the BL21(DE3) harboring the LmrR plasmid were inoculated in 10 mL of LB medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and cultured at 37°C for 4 hrs. The cells were collected by centrifugation and further inoculated into 1 L of kanamycin-M9 medium supplemented with 3 g/L d-glucose and 1 g/L 15NH4Cl as the sole carbon and nitrogen source, respectively. At an optical density at 600 nm wavelength (OD600) of 0.8, 0.6 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to induce LmrR expression. The induced culture was further incubated at 27°C for 16 hours. For the expression of deuterated LmrR, D2O-based M9 media supplemented with 3 g/L [2H7/13C6]-D-glucose or [2H7]-D-glucose was used, depending on the experimental purposes. For selective 13CH3-labeling of the Ala, Ile (Ile-δ1), Leu/Val and Met methyl groups, 50 mg/L of [3-13C, 2-2H] L-alanine, 100 mg/L of [methyl-13C, 3,3-2H2]-α-ketobutyric acid, 100 mg/L of [3-methyl-13C, 3,4,4,4-2H4]-α-ketoisovaleric acid and 50 mg/L of [methyl-13C] L-methionine were supplemented into the medium 30 min prior to the addition of IPTG. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and frozen at −80°C before purification.

The frozen pellets of LmrR-expressing cells were resuspended in lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole and the cells were disrupted by sonication. LmrR was purified from the supernatant of the cell lysate. The supernatant was applied to a 3 mL COSMOGEL His-Accept column, equilibrated with the buffer, which is same as the lysis buffer. The column was washed with 40 mL of the equilibration buffer and then LmrR was eluted with 20 ml of elution buffer, containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl and 300 mM imidazole. The eluate was concentrated by ultrafiltration, using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter unit (molecular weight cutoff 10 K; Millipore) and then passed through a 0.22 μm syringe filter for further purification by size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The sample was applied to a HiLoad Superdex 75 prep grade column (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (NaPi; pH 6.8) containing 300 mM NaCl. The elution fraction was collected, buffer-exchanged into NMR buffer containing 10 mM NaPi (pH 6.8) and 100 mM NaCl and stored at −80°C until use.

NMR experiments

All experiments were performed on either Bruker Avance-600, -700, or -800 MHz spectrometers equipped with room temperature (700 MHz) or cryogenic (600 and 800 MHz) triple resonance probes. All spectra were collected using 10 mM NaPi buffer (pH 6.8) containing 100 mM NaCl in either 90% H2O/10% D2O or 100% D2O, depending on the experiments. The typical concentration of LmrR was 0.1–0.2 mM as a monomer. Unless otherwise noted, the experiments were performed at 298 K. Spectra were processed using TOPSPIN (Bruker Biospin) and analyzed with Sparky. The backbone assignments of LmrR were accomplished using standard TROSY triple-resonance experiments. The two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of LmrR in the apo state showed good overall dispersion (Supplemental Fig. 7A); however, the backbone amide1H-15N cross-peaks could not be detected for residues 4 and 6–8 in the α1 helix and residues 96, 97, 105 and 106 in the α4 helix. The unobservable residues are all in the compound-binding site and the intensities of the mainchain resonances were weak in the entire compound-binding site (Supplemental Fig. 7B). Assignments of the Ala, Ile, Leu, Met and Val methyl resonances of LmrR were performed by combining mutational analysis, J-coupling-based triple resonance experiments ((H)CC(CO)NH, H(CCCO)NH and HCCH-TOCSY experiments) and an analysis of the inter-methyl 1H-1H NOE network, based on the crystal structures. For the Leu and Val methyl resonances, stereospecific assignments were achieved by using [2-methyl-13C, 4,4,4-2H3] acetolactate (NMR-Bio) as the precursor. The 1H–13C HMQC spectra of LmrR with assignments are shown in Supplemental Fig. 7C.

The R1 and R2 relaxation rates and the (1H)–15N heteronuclear NOEs of LmrR were measured using published 1H-detected 2D NMR pulse sequences39. The relaxation delays used were 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1200 and 1600 ms for R1 and 17, 34, 51, 68, 85, 102, 119 and 136 ms for R2 measurements. R1 and R2 values were determined by exponential fits and their uncertainties were used as the standard errors of the fitted parameters. The steady-state heteronuclear (1H)–15N heteronuclear NOEs experiments were performed using a symmetric proton irradiation scheme40. The protein saturation period before the 15N excitation pulse and the total recycling delay were set to 4.0 s and 8.0 s, respectively, to ensure the maximal development of NOEs before acquisition and to allow complete relaxation of the system. Error estimates were calculated from two separate experiments.

The rotameric equilibria of the Ile χ2, Leu χ2, Met χ3 and Val χ1 angles were deduced from the Ile (δ1), Leu, Met and Val methyl 13C chemical shifts, respectively. The 13C chemical shifts of methyl signals are reportedly dependent on the sidechain rotamer, as revealed by theoretical and experimental analyses14,16,17,18. The population of the trans rotameric state (pt) for each residue was calculated according to the chemical shift values of the methyl 13C signals (δobs; ppm) using the equations (1–4) below:

If the equation yielded a pt value >1 or <0, then the pt was fixed to 1 (all trans) or 0 (all gauche–), respectively.

To measure the order parameters of the methyl groups (S2axis) in LmrR, we employed the 1H spin-based relaxation violated coherence transfer NMR spectroscopies22,23. For this purpose, we used samples in which the methyl groups of Ala, Ile, Leu, Met and Val residues were 13CH3-labeled, in an otherwise deuterated background. The intra-methyl 1H–1H dipolar cross-correlated relaxation rates η were obtained by fitting the ratios of the peak intensities measured in pairs of data sets (i.e. forbidden and allowed data) recorded as a function of relaxation time, T, to the following equation (5):22,23.

where T is the varied delay, δ is a parameter related to the density of the external protons around the methyl group and Ia and Ib are the intensities of the forbidden and allowed coherences, respectively, with the delay T22,23. The data sets were recorded using the following sets of relaxation delays T: 1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 40 ms at 298 K. The recovery delay was set to 1.5 s.

S2axis values were calculated by the determined η value using the equation (6) below:

where τc is the rotational correlation time of LmrR, RF2,H and RS2,H are the relaxation rates of fast and slowly relaxing coherences, respectively, γH is the gyromagnetic ratio of the proton and rHH is the distance between pairs of methyl protons. The rotational correlation time was set to 20 ns and was determined by TRACT analyses41.

The normalized chemical shift perturbation values (Δδ) were calculated as follows:

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy

All SPR experiments were performed using a BIACORE3000 system (GE Healthcare) at 25°C. LmrR was immobilized to an NTA sensor chip. The binding assay was performed in HBS-P running buffer (10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 50 µM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P-20) at flow rate of 40 µL/min, using serial dilutions of compounds. Specific binding responses to compounds were obtained by subtracting the response from a flow cell that was not coated with LmrR. For the binding of daunomyin, ethidium and Rho6G, the equilibrium resonance (Req) from the SPR sensorgrams as function of the compound concentration was plotted and non-linearly fitted to a one-site binding isotherm was used to obtain the KD values. The binding constant for H33342 was determined by a kinetic analysis assuming 1:1 Langmuir binding. Analyses of the sensorgrams were performed with the BIA-evaluation Software 4.1.

ITC experiments

Calorimetric titrations of LmrR with compounds were performed with a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal) at 25°C, using the same buffer as in the NMR experiments. Protein samples were extensively dialyzed against the buffer before the experiments. The sample cell was filled with a 5–50 µM solution of protein as monomer and the injection syringe contained 100 μM of H33342, 100 µM of daunomycin, 500 μM of ethidium, or 500 µM of Rho6G. After a preliminary 3 µL injection, 24 subsequent 10 µL injections were performed. Heats were normalized by subtracting those without protein at each titration point to eliminate the effect of dilution. The data were fitted using the sequential binding site model embedded in Origin 7.0 (MicroCal).

References

Ma, D., Cook, D. N., Hearst, J. E. & Nikaido, H. Efflux pumps and drug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends in Microbiology 2, 489–493 (1994).

Saier, M. H., Jr et al. Evolutionary origins of multidrug and drug-specific efflux pumps in bacteria. Faseb j 12, 265–74 (1998).

van Veen, H. W. & Konings, W. N. Structure and function of multidrug transporters. Adv Exp Med Biol 456, 145–58 (1998).

Schumacher, M. A. & Brennan, R. G. Structural mechanisms of multidrug recognition and regulation by bacterial multidrug transcription factors. Mol Microbiol 45, 885–893 (2002).

Geick, A., Eichelbaum, M. & Burk, O. Nuclear receptor response elements mediate induction of intestinal MDR1 by rifampin. J Biol Chem 276, 14581–7 (2001).

Riordan, J. R. et al. Amplification of P-glycoprotein genes in multidrug-resistant mammalian cell lines. Nature 316, 817–9 (1985).

Bolhuis, H. et al. Proton motive force-driven and ATP-dependent drug extrusion systems in multidrug-resistant Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol 176, 6957–64 (1994).

Lubelski, J., Mazurkiewicz, P., van Merkerk, R., Konings, W. N. & Driessen, A. J. ydaG and ydbA of Lactococcus lactis encode a heterodimeric ATP-binding cassette-type multidrug transporter. J Biol Chem 279, 34449–55 (2004).

Lubelski, J. et al. LmrCD is a major multidrug resistance transporter in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol 61, 771–81 (2006).

Agustiandari, H., Lubelski, J., van den Berg van Saparoea, H. B., Kuipers, O. P. & Driessen, A. J. LmrR is a transcriptional repressor of expression of the multidrug ABC transporter LmrCD in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol 190, 759–63 (2008).

Wade, H. MD recognition by MDR gene regulators. Curr Opin Struct Biol 20, 489–496 (2010).

Agustiandari, H., Peeters, E., de Wit, J. G., Charlier, D. & Driessen, A. J. LmrR-mediated gene regulation of multidrug resistance in Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology 157, 1519–30 (2011).

Madoori, P. K., Agustiandari, H., Driessen, A. J. & Thunnissen, A. M. Structure of the transcriptional regulator LmrR and its mechanism of multidrug recognition. Embo j 28, 156–66 (2009).

Hansen, D. F., Neudecker, P. & Kay, L. E. Determination of Isoleucine Side-Chain Conformations in Ground and Excited States of Proteins from Chemical Shifts. J Am Chem Soc 132, 7589–7591 (2010).

Sabo, T. M. et al. Thermal coefficients of the methyl groups within ubiquitin. Protein Sci 21, 562–570 (2012).

Butterfoss, G. et al. Conformational dependence of 13C shielding and coupling constants for methionine methyl groups. J Biomol NMR 48, 31–47 (2010).

Hansen, D. F., Neudecker, P., Vallurupalli, P., Mulder, F. A. A. & Kay, L. E. Determination of Leu Side-Chain Conformations in Excited Protein States by NMR Relaxation Dispersion. J Am Chem Soc 132, 42–43 (2009).

London, R. E., Wingad, B. D. & Mueller, G. A. Dependence of Amino Acid Side Chain 13C Shifts on Dihedral Angle: Application to Conformational Analysis. J Am Chem Soc 130, 11097–11105 (2008).

Kofuku, Y. et al. Efficacy of the β2-adrenergic receptor is determined by conformational equilibrium in the transmembrane region. Nat Commun 3, 1045 (2012).

Imai, S., Osawa, M., Takeuchi, K. & Shimada, I. Structural basis underlying the dual gate properties of KcsA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107, 6216–21 (2010).

Brady, G. P. & Sharp, K. A. Entropy in protein folding and in protein—protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol 7, 215–221 (1997).

Sun, H., Kay, L. E. & Tugarinov, V. An Optimized Relaxation-Based Coherence Transfer NMR Experiment for the Measurement of Side-Chain Order in Methyl-Protonated, Highly Deuterated Proteins. J Phys Chem B 115, 14878–14884 (2011).

Tugarinov, V., Sprangers, R. & Kay, L. E. Probing Side-Chain Dynamics in the Proteasome by Relaxation Violated Coherence Transfer NMR Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 129, 1743–1750 (2007).

Akke, M. Conformational dynamics and thermodynamics of protein-ligand binding studied by NMR relaxation. Biochem Soc Trans 40, 419–23 (2012).

Akke, M., Brueschweiler, R. & Palmer, A. G. NMR order parameters and free energy: an analytical approach and its application to cooperative calcium(2+) binding by calbindin D9k. J Am Chem Soc 115, 9832–9833 (1993).

Yang, D. & Kay, L. E. Contributions to Conformational Entropy Arising from Bond Vector Fluctuations Measured from NMR-Derived Order Parameters: Application to Protein Folding. J Mol Biol 263, 369–382 (1996).

Li, Z., Raychaudhuri, S. & Wand, A. J. Insights into the local residual entropy of proteins provided by NMR relaxation. Protein Sci 5, 2647–2650 (1996).

Marlow, M. S., Dogan, J., Frederick, K. K., Valentine, K. G. & Wand, A. J. The role of conformational entropy in molecular recognition by calmodulin. Nat Chem Biol 6, 352–8 (2010).

Frederick, K. K., Marlow, M. S., Valentine, K. G. & Wand, A. J. Conformational entropy in molecular recognition by proteins. Nature 448, 325–9 (2007).

Tzeng, S. R. & Kalodimos, C. G. Protein activity regulation by conformational entropy. Nature 488, 236–40 (2012).

Kalodimos, C. G. NMR reveals novel mechanisms of protein activity regulation. Protein Sci 20, 773–82 (2011).

Tzeng, S. R. & Kalodimos, C. G. Dynamic activation of an allosteric regulatory protein. Nature 462, 368–72 (2009).

Popovych, N., Sun, S., Ebright, R. H. & Kalodimos, C. G. Dynamically driven protein allostery. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13, 831–8 (2006).

Sapienza, P. J. & Lee, A. L. Using NMR to study fast dynamics in proteins: methods and applications. Curr Opin Pharm 10, 723–730 (2010).

Petit, C. M., Zhang, J., Sapienza, P. J., Fuentes, E. J. & Lee, A. L. Hidden dynamic allostery in a PDZ domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106, 18249–54 (2009).

Vallee-Belisle, A., Ricci, F. & Plaxco, K. W. Thermodynamic basis for the optimization of binding-induced biomolecular switches and structure-switching biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106, 13802–7 (2009).

Lange, O. F. et al. Recognition dynamics up to microseconds revealed from an RDC-derived ubiquitin ensemble in solution. Science 320, 1471–5 (2008).

Kasinath, V., Sharp, K. A. & Wand, A. J. Microscopic insights into the NMR relaxation-based protein conformational entropy meter. J Am Chem Soc 135, 15092–100 (2013).

Brooks, B. E., Piro, K. M. & Brennan, R. G. Multidrug-Binding Transcription Factor QacR Binds the Bivalent Aromatic Diamidines DB75 and DB359 in Multiple Positions. J Am Chem Soc 129, 8389–8395 (2007).

Ferrage, F., Cowburn, D. & Ghose, R. Accurate Sampling of High-Frequency Motions in Proteins by Steady-State 15N−{1H} Nuclear Overhauser Effect Measurements in the Presence of Cross-Correlated Relaxation. J Am Chem Soc 131, 6048–6049 (2009).

Lee, D., Hilty, C., Wider, G. & Wüthrich, K. Effective rotational correlation times of proteins from NMR relaxation interference. J Magn Reson 178, 72–6 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Japan New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI; to I.S.). Funding was also provided by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (24370048 and 25121743 to K. T.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and by JST, PREST (to K.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.T., Y.T., H.T. and I.S. conceived the project. K.T. and I.M. performed the experiments. K.T., Y.T., H.T. and I.S. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supplemental figures

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Takeuchi, K., Tokunaga, Y., Imai, M. et al. Dynamic multidrug recognition by multidrug transcriptional repressor LmrR. Sci Rep 4, 6922 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06922

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06922

This article is cited by

-

Rationally introducing non-canonical amino acids to enhance catalytic activity of LmrR for Henry reaction

Bioresources and Bioprocessing (2024)

-

The importance of catalytic promiscuity for enzyme design and evolution

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2019)

-

PadR-type repressors controlling production of a non-canonical FtsW/RodA homologue and other trans-membrane proteins

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Dynamic regulation of GDP binding to G proteins revealed by magnetic field-dependent NMR relaxation analyses

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Dynamic equilibrium on DNA defines transcriptional regulation of a multidrug binding transcriptional repressor, LmrR

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.