Key Points

-

Introduces, through a favourable pilot study, enhanced functionality to the Denplan PreViser Patient Assessment on line tool (DEPPA). This enhancement provides evidence-based support in communicating oral health status and risk with young patients (under 17) and their parents/carers.

-

Incorporates numerical oral health status and risk scoring, which is intended to facilitate the audit of individual patient progress. In time it is planned that benchmarked group audit will become available, so that the progress of oral health policies can be monitored.

-

Opens the possibility of using oral health status and risk scores in order to band young patients for capitation fee guidance.

Abstract

Aim To test the validity and acceptability of an online oral health assessment and biofeedback tool for young patients (under 17) for use in general dental practice.

Methods A convenience sample of thirteen practitioners were recruited to test the functionality of a novel version of the Denplan PreViser Patient Assessment tool (DEPPA) developed for young patients (YDEPPA). Dentists who had completed eight or more assessments during a one month window were sent a link to an online feedback survey, comprising eight statements about YDEPPA, with scoring options of 0–10, where a score of 10 indicated complete agreement with the relevant questions. Verbatim comments were encouraged. The clinical data submitted were held in a central database in an encrypted format so that only the user practice could identify individual patients.

Results Twelve practitioners completed eight or more assessments and were included in the survey. A total of 175 patient assessments were received. Ten practitioners completed the on-line survey. The statement 'YDEPPA produces a valid measurement of each patient's oral health' received an average feedback score of 8.8. The statement 'The full YDEPPA report is a valuable communication aid' received a score of 9.6. Feedback was generally very positive with all scores >8.2. Constructive critical feedback was received for the caries risk aspect of the YDEPPA protocol, with suggestions made for improving objectivity of data inputs. Eighty-one percent of the verbatim comments received were positive.

Conclusions Once the caries risk issues raised by pilot dentists have been addressed, YDEPPA appears suitable as a pragmatic analytical and biofeedback tool for use in general dental practice to assess the oral health of young patients, and to facilitate education and engagement of young patients and their parents/carers in positive health behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A validated risk assessment tool has been shown to predict periodontitis and associated tooth loss in untreated patients with a high degree of accuracy and validity.1,2 This tool, along with two further systems also appears to predict bone loss and tooth loss in treated patients on periodontal maintenance programmes.3,4,5

A recent European consensus based on systematic reviews of the scientific literature concluded that brief interventions on risk factor control were beneficial for the primary and secondary prevention of oral diseases.1 One of those systems, PreViser™ underpins the Denplan PreViser Patient Assessment tool (DEPPA) for adult patients (17 and over), the development and validation of which has been previously reported.6,7,8,9 Moreover, the PreViser system has been shown to improve psychological parameters associated with positive cognitive behaviours and self-efficacy in adult patients.10 More recently, biofeedback for the same system was reported to significantly improve oral hygiene behaviours of adults and, for the first time, to significantly improve clinical outcomes by reducing plaque and gingival inflammation scores after 3-months.11 However, to date no such system has been reported for use in children and young adults, therefore this paper reports the development of a similar online system for assessing young patients using DEPPA and its evaluation by practitioners regarding functionality.

As part of its practice certification programme Denplan Excel, Denplan Ltd launched Denplan Excel for Children in 2008. A revised version was released in 2013.12 This programme included protocols for a separate oral health assessment (a clinician assessment of dental status and future disease risk) and an oral wellbeing assessment encompassing patient/parental perceptions of the young person's oral health. A red, amber and green (RAG) report presentation format was developed in order to support patient understanding and motivation. However, these assessments were paper based and in 2016 it was decided to add functionality to DEPPA to extend the electronic adult assessment system to young patients. The protocols for adult DEPPA, the oral health assessment and the oral wellbeing assessment were taken as the starting point for development. A working title of Young DEPPA (YDEPPA) was assigned to the enhanced functionality.

Development of YDEPPA

The same team that led the development of adult DEPPA comprising a senior dental adviser from Denplan, the Managing Director of OHI Ltd (the UK licence holders for PreViser) and a professor of periodontology were joined by a consultant in paediatric dentistry who had acted as the lead adviser in the revision of Denplan Excel for Children in 2013. This core team are grateful to the many colleagues who also generously provided their valuable time, expertise and input during the development period.

The impetus for YDEPPA and the factors that guided the development of the protocol for practitioner testing were:

-

1

The recognition that a significant majority of hospital-performed extractions in young patients are focused within a minority of high risk patients, with significant regional oral health inequalities existing in 5–9-year-olds13

-

2

The realisation that oral health inequalities are evident as early as 3–4 years of age in specific minority populations with high needs14

-

3

The demonstration that chronic periodontitis may start developing in the early teens in specific risk groups and have progressed significantly by 19 years of age15,16

-

4

The need to build on the strengths and success of adult DEPPA and create a system for younger people that included the use of RAG score reporting to facilitate patient engagement in behaviour change. Numerical scoring in the adult version has also proved valuable both in the audit of individual patient progress and in group clinical audits7

-

5

The need to establish protocols for oral health and risk scoring that are evidence-based and specific to young patients. The revised manual for Denplan Excel for Children12 (2013) proved to be a very valuable resource in this respect

-

6

The need to create a tool for general dental practice that was simple and practical to help support practices to be effective and efficient in their care of younger patients

-

7

The evidence base for risk factors in child oral health is less mature than for adult oral health, although progress is being made particularly in the area of caries risk in young patients.17

These factors led to the development of a composite protocol for YDEPPA for piloting in general dental practice that included patient oral health self-perceptions, the clinical assessment of oral health status and simple assessments of caries risk and the risk of tooth erosion.

Overview of the pilot version of the YDEPPA protocol

The protocol followed the convention from the oral health score (OHS) of adult DEPPA that 100 points should represent perfect oral health. Ten factors were considered necessary in order to construct a composite assessment score for young patients (Table 1).

Adult DEPPA employs separate scores (calculated by evidence-based algorithms) to the OHS for future risk of caries, periodontal disease, tooth wear and oral cancer. As illustrated in Table 1, simple risk scores for caries and tooth erosion were incorporated into the composite protocol of YDEPPA as subsections of the main disease status scores. No attempt was made to construct complex algorithms for risk scoring, or to score periodontal disease risk or oral cancer risk, as the current body of evidence for young patients was deemed insufficient for such an approach at the present time.

As summarised in Table 1, tooth health was recorded across four separate domains:

-

Aspect 4 Caries

-

Aspect 5 Tooth wear

-

Aspect 6 Tooth development abnormalities

-

Aspect 7 Dento-alveolar trauma.

Aspects 6 and 7 do not specifically feature in adult DEPPA but were considered as essential in the assessment of young patients. In adult DEPPA defective restorations are recorded in addition to caries activity. There was no option to record defective restorations in the pilot version of YDEPPA unless the defect in question had been caused by caries activity. Any odontogenic infections with pus caused by advanced caries (for example, abscess or sinus tract) were recorded in the 'soft tissues' aspect of the system.

The periodontal health inputs for YDEPPA were based on The British Society of Periodontology and The British Society for Paediatric Dentistry guidelines for a Basic Periodontal Examination of Children.16 From these inputs, a simple formula calculated one of the five disease status categories for each patient (see Table 1).

Supplementary Figure 1 (online) illustrates a screen view of the input options available for each patient assessment and the reports produced by YDEPPA.

A second page of the report offers preventive advice tailored to two age bands: 3–6 and 7+ and includes a box for the dentist/patient to complete a personal target to focus on between visits.

The principle aim of this study was to evaluate the validity and acceptability of YDEPPA in a general dental practice setting.

Materials and methods

Denplan Ltd contracts a team of about 30 practice advisers, who are general dental practitioners. The principal function of this team is to conduct practice visits to confirm compliance with Denplan Excel Certification standards. This team are deliberately recruited with geographic spread to cover the whole of the United Kingdom. All members of this group are DEPPA users. The eight most prolific users from this list were contacted by email and asked to test the functionality of the YDEPPA system. Seven of this group volunteered. These advisers had conducted an average of more than 200 DEPPAs each by this time. Additionally, a further 700 dentists are registered to use DEPPA. The seven most prolific users of DEPPA, who were not practice advisers, were also contacted by email and asked to test the YDEPPA functionality. This group had conducted an average of more than 1000 DEPPAs each by this time. All seven volunteered providing a convenience sample of thirteen practitioners recruited to the pilot study. Seven of this group were female and six male. They were located in England (eight), Scotland (four) and Wales (one) at a total of 11 different practices.

YDEPPA functionality was added to the online accounts of these 13 practitioners and they were asked to assess a minimum of ten young patients each during a one-month window. Each dentist was sent a draft protocol of YDEPPA that included written guidance to support input selections for each aspect of the assessment.

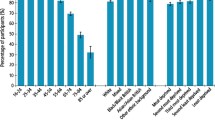

At the end of the month a link was sent by email to the online survey instrument to elicit feedback from the 12 dentists who completed eight or more patient assessments. The questions asked in this survey are documented in Figure 1. Each practitioner was offered scoring options from 0–10 for each statement. The more they agreed with each statement the higher they were instructed to score. After each statement there was an option for qualitative comments. A reminder e–mail was sent four days later to members of the study group who had failed to complete the questionnaire at that time.

The clinical data submitted were held in a central database in an encrypted format so that only the user practice could identify individual patients.

Results

One member of the 13 within the study group was able to submit only a single assessment due to a lack of child appointments in the pilot period. The remaining 12 volunteers submitted between 8–30 assessments, providing a total of 175 submissions, an average of 14 assessments per dentist. Ten of the dentists completed the online survey, equating to an 'intention to treat' response rate of 83% and a 'per-protocol' response rate of 77%. Their feedback is summarised in Figure 1.

Discussion

The feedback scores shown in Figure 1 demonstrate that this study group were very favourably disposed to the new functionality offered by YDEPPA. Table 2 illustrates that the majority of comments (81%) were positive.

However, it should be noted that this group of ten practitioners providing feedback were drawn from the most prolific users of adult DEPPA and therefore represent a biased sample, as they are likely to be a particularly enthusiastic group in respect of the perceived value of digital risk assessment tools in general dental practice. Conversely, it could also be argued that their feedback was more likely to offer greater insight than that from less experienced users, due to their significant experience using such tools.

The main criticisms of the pilot version of YDEPPA related to the caries risk aspect. Figure 1 illustrates that practitioners were asked to make their own judgements on dietary risk by questioning their patients. This group was accustomed to using the adult evidence-based algorithms developed by PreViser for disease risk scoring. This aspect of YDEPPA may require further development before a full launch.

The average score of 8.8 for question three in the survey gives some support to the content validity of YDEPPA. This score compares favourably with a similar validity score obtained with the OHS aspect of adult DEPPA (8.6) when it was piloted in 2013.6 Subsequently, the adult OHS was subjected to further criterion and construct validation with favourable results.7,8,9

The adult DEPPA database, which like that for YDEPPA is encrypted (to preserve patient confidentiality), now holds over 95,000 assessments and has provided a valuable national benchmark to support clinical audit in individual practices and also to enable the generation of population oral health studies.6,7,8,9 The authors believe that this will also be the case with YDEPPA, once a database of significant size has been established and it is anticipated that in time, the data may be best analysed in age groups (for example, under 8, 8–12, and 12–16) to provide meaningful benchmarks and comparisons with clinical data from other studies. It is intended that this will be the subject of further study by the authors.

Adult DEPPA also calculates fee code guidance for private capitation contacts based upon disease status and future risk (currently a range of five fee codes A–E). DEPPA database analysis enables the average oral condition of the patients in each fee group to be studied and hence an estimation of the practice care time likely to be required for each of the five groups to be determined. The authors believe that, in time, it will be possible to adopt a similar protocol for young patients using YDEPPA data. It is estimated that three fee codes (Low need, moderate need and high need) may suffice. This is also intended to be the subject of further study.

Conclusions

Once the dietary caries risk issues raised by pilot dentists have been addressed, YDEPPA appears suitable as a pragmatic analytical and biofeedback tool for use in general dental practice. YDEPPA will allow dental teams to measure the oral health of young patients as an additional functionality to adult DEPPA, and to report findings using RAG codes to facilitate education and engagement of young patients and parents/carers.

There are strong indications from this pilot study that YDEPPA is likely to be a valuable communication tool in the care of young patients with the potential to engage young patients and their parents and support the adoption of positive health behaviours. With its numerical scoring it should become a valuable tool with which to audit individual patient progress, similar to its adult counterpart.

The centralised and anonymous method of data collection is likely to support practice clinical audits, young population oral health studies and fee code calculation in the future.

References

Lang N, Suvan J, Tonetti M. Risk factor assessment tools for the prevention of periodontitis progression a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2014; 42 (Suppl. 16): S59–S70.

Page R C, Martin J, Krall E A, Mancl L, Garcia R. Longitudinal validation of a risk calculator for periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2003; 30: 819–827.

Martin J, Page R C, Loeb C, Levi P A Jr. Tooth loss in 776 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol 2010; 81: 244–250.

Lang N P, Tonetti M S. Periodontal risk assessment (PRA) for patients in supportive periodontal therapy (SPT). Oral Health Prevent Dent 2003; 1: 7–16.

Trombelli L, Minenna L, Toselli L et al. Prognostic value of a simplified method for periodontal risk assessment during supportive periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol 2017; 44: 51–57.

Busby M, Matthews R, Chapple E, Chapple I. Novel online integrated oral health and risk assessment tool: development and practitioners' evaluation. Br Dent J 2013; 215: 115–120.

Busby M, Chapple E, Matthews R, Burke F J T, Chapple I. Continuous development of an oral health score for oral health surveys and clinical audit. Br Dent J 2014; 216: 526–527.

Busby M, Martin J, Matthews R, Burke F J T, Chapple I. The relationship between oral health risk and disease status and age, and the significance for general dental practice funding by capitation. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 576–577.

Sharma P, Busby M, Chapple L, Matthews R, Chapple I. The relationship between general health and lifestyle factors and oral health outcomes. Br Dent J 2014; 221: 65–69.

Asimakopoulou K, Newton T, Daly B, Kutzer Y, Ide M. The effects of providing periodontal disease risk information on psychological and clinical outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42: 350–355.

Asimakopoulou K, Nolan M, McCarthy C, Newton T. the effects of goal-setting, planning and self-monitoring (GPS) on behavioural and periodontal outcomes: A randomised controlled trial (RCT). IADR 2017, abstract 0371.

Denplan. Denplan Excel. Available at www.denplan.co.uk (accessed August 2017).

Faculty of Dental Surgery, Royal College of Surgeons of England. The state of children's oral health in England. 2015. Available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/about-rcs/government-relations-consultation/childrens-oral-health-report-final.pdf (accessed August 2017).

Marcenses W, Muirhead V E, Murray S, Redshaw P, Bennett U, Wright D. Ethnic disparities in the oral health of 3–4 year-old children in East London. Br Dent J 2013; 215: e4.

Clerehugh V, Lennon M A, Worthington H V. 5-year results of a longitudinal study of early periodontitis in 14to 19yearold adolescents. J Clin Periodontol 1990; 17: 702–708.

British Society of Periodontology and British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. Guidelines for periodontal screening and management of children and adolescents under 18-years of age. 2012. Available at http://www.bsperio.org.uk/publications/downloads/54_090016_bsp_bspd-perio-guidelines-for-the-under-18s-2012.pdf (accessed August 2017).

Twetman S. Caries risk assessment in children: how accurate are we? Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2016; 17: 27–32.

Clerehugh V, Kindelan S. Executive Summary – Guidelines for Periodontal Screening and Management of Children under 18 years of age. British Society of Periodontology and The British Society for Paediatric Dentistry. 2012. Available at https://www.bsperio.org.uk/publications/downloads/53_085556_executive-summary-bsp_bspd-perio-guidelines-for-the-under-18s.pdf (accessed August 2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figure (PDF 2145 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Busby, M., Fayle, S., Chapple, L. et al. Practitioner evaluation of an online oral health and risk assessment tool for young patients. Br Dent J 223, 595–599 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.841

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.841