Key Points

-

The greater use of skill mix in dentistry continues to lag behind medicine, where its use in both primary and secondary care environments is widespread.

-

Previous research has demonstrated that financial constraints are a problem to the wider use of skill mix in dental practices.

-

This paper assesses the financial incentives for utilising skill mix in general dental practice under the current National Health Service contract.

Abstract

The use of skill mix in medicine is now widespread, yet it appears that its use in dentistry is not as prominent. Unlike doctors, dentists are required to mitigate the financial risk produced by their capital investment and ensure an adequate cash flow to cover their annual running costs. Examining the financial incentives for employing dental care professionals is therefore an important step to understand why dentistry appears to lag behind medicine in skill mix. It is also apposite, given the announcement of the coalition government to develop a new contract, which could introduce incentives for the use of dental care professionals in this way. The purpose of this short paper is to examine whether skill mix is profitable for general dental practices under the existing NHS contract in England.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although much of the burden of dental caries is borne by socially disadvantaged groups,1,2 the oral health needs of the population are changing in the United Kingdom. Overall, there has been a broad shift towards better oral health, due to widespread exposure to fluoride, changes in diet and improvements in oral hygiene.3,4 This is expected to continue,5 resulting in a situation where the majority of younger individuals have low treatment needs compared to older dentate cohorts who have become trapped in the 'restorative cycle'.6 However, the service requirements that stem from these evolving needs are being met by a service that has not changed significantly, despite the 2006 revision in the National Health Service (NHS) contract in the wake of Options for change.7 Much of the public funds continues to be spent on repairing the effects of the disease, despite dental caries being a preventable disease.1

Overall, utilisation of dental services is determined by both demand and supply factors; these include social norms in different communities, an individual's ability and willingness to incur the costs of attending for treatment, how services are organised and the incentives in the NHS contract which drive dentists' behaviour.8 This often means that those in most need do not use the service,1 while those from more affluent sections of society, with lower levels of disease, attend on a regular basis, thereby promoting an 'inverse care law'.9,10 Regular attendance may indeed cause the lower levels of disease experienced in this group. However, it may equally reflect a lower number of risk factors in those who attend on an asymptomatic basis in response to supply-side factors like recall and requirements to remain with a dentist.

Shaw et al.1 argue that there is an ethical obligation upon the profession to anticipate and prevent disease rather than manage its consequences. These are important observations, and although the ethical perspectives of practitioners may shape the service in the private sector, the responsibility in the NHS rests with both the dentist and those charged with the statutory duties of commissioning and financing NHS dental services. This is particularly pertinent given the imminent need to reduce public expenditure, highlighted in the recently published 'Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention' (QIPP) agenda of the Department of Health11 and the direction provided by the Steele review,12 which argues for a shift from provision of dental activity to oral health improvement.

One such model to achieve these aims is the greater use of different skill mixes, where prevention and less complex procedures are undertaken by dental care professionals (DCPs), leaving dentists to examine and diagnose, formulate treatment plans and engage in more complicated procedures. This has been argued to be more economic13 and has attracted attention recently.12,14 This paper aims to provide a pragmatic worked example to explore the profitability of utilising skill mix in the current NHS contract in England.

Skill mix in medicine

'Team working' is an area where the dental profession has lagged behind medical colleagues.6 In medicine, nurses or auxiliary staff can either supplement or substitute the services provided by doctors, depending on their skill base and legislated scope of practice.15 The former is a term to describe how nurses provide services which are in addition to and complement or extend those services provided by doctors, while the latter is where services previously provided by doctors are undertaken by nurses. The former is likely to increase health service costs, while the latter is likely to reduce costs. These terms are important conceptually as they identify the role to be played by an individual and the impact this has on the economic viability of the model used.

A review of research into the substitution of nurses for doctors suggested that 25% to 70% of the work undertaken by doctors could be undertaken by nurses,16 thereby providing a key role in health promotion17 and the routine management of chronic diseases.18 However, recent reviews have highlighted some of the problems of using skill mix within medicine. Laurant et al.,15 Horrocks et al.19 and Brown and Grimes20 all found that nurse-led care was associated with higher levels of patient compliance and satisfaction, but that these were also associated with longer consultation appointments and higher numbers of special tests, leading to a greater number of recall appointments. As a result, the economic benefit produced by the reduced cost of using nursing staff was offset by their increased use of resources and lower productivity. As a result, Laurent et al.15 concluded that the addition of nurses to physician teams may not reduce workload unless the time freed up for doctors is invested in activities that only doctors can perform.

Is skill mix viable in dentistry?

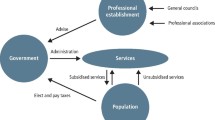

The direct comparison between general dental practitioners (GDPs) and general medical practitioners (GMPs) in primary care in the UK is a little unfair, given that the latter discipline does not bear the significant capital costs and responsibility for running a business.8 Unlike GMPs, the GDP not only undertakes the examination and diagnosis but they also perform the majority of their patients' operative treatment. Finally, there are far fewer disease categories, which may further impact upon the scope for skill mix given the more limited number of roles required. Fundamentally, because of the structure of the remuneration system, the delivery of dental services in the UK bears as much resemblance to a business model as it does to a health model. In such a market, satisfying the demand for consumers can become as important as meeting the needs of a given population21 and is predicated on good health literacy,22 that is, patients' 'wants' may exceed patients' needs. As such, it is pertinent to examine the incentives for the practitioner to engage in skill mix in the 2006 contract in England.

Therapists

Therapists have been seen as a cost-effective option in the past23 given their lower cost, and this has been enhanced further with an increase in their extended duties24 and ability to work without direct supervision in general dental practice. However, it would appear that their viability under the existing contract is being called into question. According to Williams et al.,25 'dentists cannot see any financial gain' in deploying skill mix and as therapists become more highly trained, it has been argued that their unit cost increases.26

To examine the financial contribution of the therapist to a practice under the current General Dental Services contract in England, a simple worked example is presented. Empirical data were collected on the timings of routine treatments concurrent with a study examining the outcomes of treatment provided in NHS general dental practice (Table 1). This study was conducted in the North West of England and involved 38 dental practices. Data on appointment time length were collected on 510 adult patients aged between 18 and 60 years, 477 of whom had single treatment interventions during one visit.

The worked example models the impact of substitution in a two-person practice, where an associate dentist working with a principal (Model 1) (Table 2) is compared to a situation where 80% of the principal's routine restorations are referred to a therapist, to free up time for more complex Band 3 treatment (Model 2) (Table 3). The current cost of employing the associate, that is, the associate split, is modelled as 50% and it is assumed that the Units of Dental Activity (UDA) rate is £25 per UDA. It is also assumed that the therapist earns £25 per hour and generates 4 UDAs per hour. Following a review of Table 1, appointment times were set at 15 min for a Band 1, 30 min for a Band 2 and 60 min for a Band 3. Laboratory fees are charged at 3 UDAs and the term relative profit ratio (RPR) is used to describe the ratio between the income generated by Model 2 over Model 1.

Table 4 contrasts the different costs and benefits of the two models. The RPR for Model 2 is £220.75 ÷ £186.75 = 1.18, which would appear to be marginal. Undertaking a sensitivity analysis on the RPR based on variations in the extent of the associate split and the number of UDAs generated per hour by the therapist reveals just how marginal any advantage of substitution is (Table 5). Should the principal of the practice reduce their associate share from 50% to 40%, the marginal benefit between a therapist and associate deteriorates further. Indeed, if the free time generated by the therapist is invested in increased new patient activity, based on 15 minutes per patient, there is no advantage offered by substitution in the NHS (RPR = 0.99).

It is recognised that this is an over-simplification of the complexities in general dental practice and that a number of assumptions have been made:

-

1

The principal will be able to simply replace Band 2 activity with the more UDA-rich Band 3 activity and this would depend on adequate numbers of patients with this treatment need in the practice population, that is, this represents the best-case scenario

-

2

Band 3 payments attract a laboratory fee, which varies according to the type of appliance prescribed, although this band is still likely to be more UDA-rich per hour than Band 2

-

3

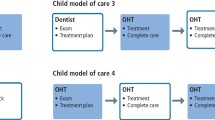

Unlike associates, therapists cannot currently prescribe their own treatment plans and so their earning potential is 2 UDAs per Band 2 payment (3 UDAs less 1 UDA for examination by the principal). As it may be necessary to see the patient for a number of restorations over a number of visits, this decreases earning potential as the UDA rate is reciprocally linked to the number of visits and the time taken at the appointment. Figure 1 provides a simple model of the impact on the production of UDAs versus appointment length and number of visits

-

4

There is a pressure on the principal to stimulate demand for the therapist and careful treatment planning would be necessary to avoid 'down time'

-

5

Some restorative cases may be referred back if teeth require root filling and so exceed the scope of practice for a therapist.27 This could mean that it is simpler to employ an associate who can undertake all possible treatment options

-

6

Given the possibility for over-supply of dentists into the workplace in the future, the share of profits that the associate retains is likely to reduce

-

7

Questions remain about the social acceptability of substitution and the role of therapists in general practice.28,29 Current research suggests that the response of patients to therapists can be varied and relates to the type of treatment being provided28,29

-

8

These figures are based on data from the North West and so there may be regional variations in the distribution of Band 1, 2 and 3 treatments undertaken

-

9

This model represents the relative profitability from a practice perspective only and so does not account for a societal or health system perspective

-

10

Band 3 often involves Band 2 care in more complex cases.

Although it has been argued that the inclusion of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) may encourage substitution,25,30 for example, the PDS Plus contract, these would need to significantly add to the revenue potential of practices to be of interest. In addition, without professional independence to examine and plan treatments, there remains real pressure on the referral structures within the practice to create sufficient demand to make therapists cost-effective, although there is evidence that patients are satisfied with the care provided by therapists29 analogous to the findings of Laurent et al.15

Hygienists

The situation for hygienists is very different despite having fewer clinical skills,25,31 as they appear to have a discrete role that makes a financial contribution to the practice. From a business perspective, Band 1 treatment plans can be 'upsold' to Band 2 payments, as the management of periodontal disease is extended over a number of appointments for 'necessary non-surgical periodontal treatment'. In addition, as hygienists often work alone, their direct costs will be less and so their potential to generate income is increased further. It would also appear that their role is more distinct and there are arguably fewer occasions in the management of periodontal disease where the hygienist may find themselves at the extremes of their clinical competence. This means that the service that the hygienist offers is a supplement to, rather than a substitution of, the dentist's skills. In this manner, hygienists are given a distinct domain to own, which requires less effort from the practitioner to ensure continued demand and is perhaps one reason why many therapists are undertaking a high proportion of hygiene duties in their clinical practice.25,32

Extended duty dental nurses

Since the publication of Scope of practice,24 it is now possible for extended duty dental nurses (EDDNs) to apply fluoride, and recent guidance from the Department of Health33 on the use of fluoride varnish by dental nurses to control caries would appear to suggest that the Department of Health sees a role for the EDDN in the practice setting. Given the simplicity of the procedure, the potential revenue generated per hour would appear to be promising.

According to Milsom et al.,34 14.3% of three- to six-year-old regular attenders developed a new cavity in subsequent appointments if they had caries at baseline. This is compared to 2.3% in those that were caries-free at baseline, although once one tooth had become cavitated, the rate of progression of new lesions was similar across both groups in the three-year period of observation. Based on evidence from a number of systematic reviews,35 Delivering better oral health36 argues that twice-yearly applications can produce a mean caries increment reduction of 33% in the primary dentition. However, the fee structure within the 2006 contract again works as a disincentive, as the revenue generated by applying fluoride varnish is offset by the need for an examination before the prescription is made. This means that the potential of EDDNs to add income to the practice is limited to intervals between examinations and is reliant on patients returning for their appointment. In addition, for those patients who are at high risk, there is an incentive for the dentist to review their own patients every three months from an ethical and financial perspective.

Table 6 demonstrates the impact of this on practice income across four recall intervals based on risk for patients with and without the disease. A simple recall strategy has been modelled where children are seen at 12-month, six-month and three-month intervals for low-, medium- and high-risk individuals, with the application of fluoride at six, three and three months respectively. From the perspective of income generation, this highlights the incentive for the dentist to see the patient every three months, as there is a potential to earn either a further 1 UDA for an examination and fluoride application or a further 3 UDAs for a restoration, should a lesion arise in this time period. The need to source additional chairside support to provide cover while the nurse is on extended duties is a further disincentive for dentists to currently utilise EDDNs, coupled with a likely willingness for dentists to monitor patients that are of concern.

Discussion

Unlike in medicine, there would appear to be a number of financial constraints in the structure of the current NHS dental contract that prevent the profitability and effective use of skill mix. As highlighted above, the most important of these barriers is that the examination undertaken by the referring dentist prevents any further earning potential for additional Band 1 treatments in the current contract in England and reduces the financial reward for the practice for Band 2 treatments from three to two UDAs. Such a remuneration structure means that there are significant pressures placed within the referral system at a practice to create sufficient demand to make therapists and EDDNs viable. However, given their lower direct cost, their ability to 'upsell' treatment plans and their potential for shorter appointment times, hygienists enjoy a very different role from a financial perspective and appear to be well accepted in their clinical role both by practice principals and the public.

Given the historical development of NHS dentistry, where practitioners have had to function as a business in order to offset their capital risk and ensure fluidity, the delivery of care from general practice will be heavily influenced by the need to ensure liquidity and capital growth. As such, it would appear that irrespective of their ethical obligation to the profession,1 dentists may feel that they owe an equal or perhaps greater obligation to the survival of their businesses. The problem this creates is that there is an increasing dissonance between the needs and wants of the population they serve.37 However, it is recognised that in some areas, the local population has not shared in the general improvement in oral health, and that dental priorities remain heavily occupied with restorations among both adult and child patients.

While this developing tension between dentistry as a business and dentistry as a healthcare profession has been allowed to exist up until now, the current change in the economic climate38 and the resultant response from the Department of Health11 mean that this situation is unlikely to persist well into the future, particularly given the recommendations of Steele and the focus upon health outcomes.12

To enable skill mix to flourish there is either a need to reconsider the current scope of practice,24 with a view to providing greater flexibility for DCPs to manage their own patients in a similar manner to those practices adopted in New Zealand,30 or a need for a change in the current structure of delivery to reflect the future needs and demands of the population. The coalition government's recent announcement that they intend to introduce a new contract suggests that it is an appropriate time to reconsider the role of skill mix in dentistry and generate financial incentives for its use.39

Conclusion

Unlike medicine, primary care dentistry is fundamentally operated as a business and this paper demonstrates that the current NHS contract places pressure on the referral and appointment structures within a practice to maintain financial viability. This acts as a disincentive to the use of therapists and EDDNs, which means that practices remain 'top-heavy' as the most skilled and expensive clinicians are being utilised to manage a population whose oral health is rapidly improving. It is an apposite time to reconsider appropriate financial incentives for skill mix, given the impending redesign of the NHS contract in England.

References

Shaw D, Macpherson L, Conway D . Tackling socially determined dental inequalities: ethical aspects of Childsmile, the national child oral health demonstration programme in Scotland. Bioethics 2009; 23: 131–139.

Godson J H, Williams S A . Inequalities in health and oral health in the UK. Dent Update 2008; 35: 243–250.

Office for National Statistics. Adult dental health survey: oral health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: Office for National Statistics, 1998. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/dh0999.pdf.

Office for National Statistics. Children's dental health in the United Kingdom 2003. London: Office for National Statistics, 2003.

NHS National Workforce Projects. Dental workforce resource pack. Manchester: NHS National Workforce Projects, 2005.

Gallagher J E, Wilson N H . The future dental workforce? Br Dent J 2009; 206: 195–200.

Department of Health. NHS dentistry: options for change. London: The Stationery Office, 2002.

National Institute for Health Research. The impact of incentives on the behaviour and performance of primary care professionals. London: The Stationery Office, 2010. http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/files/project/158-exec-summary.pdf.

Milsom K M, Jones C, Kearney-Mitchell P, Tickle M . A comparative needs assessment of the dental health of adults attending dental access centres and general dental practices in Halton & St Helens and Warrington PCTs 2007. Br Dent J 2009; 206: 257–261.

Hart J T. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971; 1: 405–412.

Department of Health. Implementing the Next Stage Review visions: the quality and productivity challenge. London: Department of Health, 2009. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Dearcolleagueletters/DH_104239.

Steele J. Review of NHS dental services in England. London: Department of Health, 2009.

McGlashan G, Watson D J, Shanks S . Professionals complementary to dentistry: the expanding role of PCDs. Dent Update 2004; 31: 529–532.

Drinkwater C. Local commissioning: opportunity or threat? London: British Dental Association, 2009.

Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B . Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 2: CD001271.

Richardson G, Maynard A, Cullum N, Kindig D . Skill mix changes: substitution or service development? Health Policy 1998; 45: 119–132.

Imperial Cancer Research Fund OXCHECK Study Group. Effectiveness of health checks conducted by nurses in primary care: final results of the OXCHECK study. BMJ 1995; 310: 1099–1104.

Aubert R E, Herman W H, Waters J et al. Nurse case management to improve glycemic control in diabetic patients in a health maintenance organization. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129: 605–612.

Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C . Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ 2002; 324: 819–823.

Brown S A, Grimes D E . A meta-analysis of nurse practitioners and nurse midwives in primary care. Nurs Res 1995; 44: 332–339.

Wright J, Williams R, Wilkinson J R . Development and importance of health needs assessment. BMJ 1998; 316: 1310–1313.

Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int 2000; 15: 259–267.

Woolgrove J, Boyles J . Operating dental auxiliaries in the United Kingdom – a review. Community Dent Health 1984; 1: 93–99.

General Dental Council. Scope of practice consultation. London: General Dental Council, 2008. http://www.gdc-uk.org/NR/rdonlyres/CEADC21D-53B5-4B00-99EC-AB69F46585D4/75351/ScopeofPracticeconsultation2008.pdf

Williams S A, Bradley S, Godson J H, Csikar J I, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 3. Financial aspects of current working practices. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 477–483.

Harris R, Burnside G . The role of dental therapists working in four PDS pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost-effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 491–496.

Ward P. The changing skill mix – experiences on the introduction of the dental therapist into general dental practice. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 193–197.

Dyer T A, Humphris G, Robinson P G . Public awareness and social acceptability of dental therapists. Br Dent J 2010; 208: E2.

Sun N, Burnside G, Harris R . Patient satisfaction with care by dental therapists. Br Dent J 2010; 208: E9.

Rowbotham J S, Godson J H, Williams S A, Csikar J I, Bradley S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 1. Developments in therapists' training and role. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 355–359.

McKendrick A J. The economics of caries prevention by dental hygienists. Public Health 1971; 85: 219–227.

Godson J H, Williams S A, Csikar J I, Bradley S, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 2. A survey of reported working practices. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 417–423.

NHS Primary Care Commissioning. The use of fluoride varnish by dental nurses to control caries. London: Department of Health, 2009.

Milsom K M, Blinkhorn A S, Tickle M . The incidence of dental caries in the primary molar teeth of young children receiving National Health Service funded dental care in practices in the North West of England. Br Dent J 2008; 205: E14.

Marinho V C C, Higgins J P T, Logan S, Sheiham A . Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002; 2: CD002279.

Department of Health, British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention – second edition. London: The Stationery Office, 2009.

Birch S. The identification of supplier-inducement in a fixed price system of health care provision. The case of dentistry in the united kingdom. J Health Econ 1988; 7: 129–150.

National Audit Office. Maintaining financial stability across the United Kingdom's banking system. London: The Stationery Office, 2009.

HM Government. The Coalition: our programme for government. London: Cabinet Office, 2010.

NHS Business Service. NHS Dental Services login page. Available at: https://www.eservice.dpb.nhs.uk/apps/welcome.html. Accessed 18 March 2011.

NHS Information Centre. NHS Dental Statistics for England: 2008/09. Available at: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/primary-care/dentistry/nhs-dental-statistics-for-england:-2008-09. Accessed 18 March 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brocklehurst, P., Tickle, M. Is skill mix profitable in the current NHS dental contract in England?. Br Dent J 210, 303–308 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.238

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.238

This article is cited by

-

Timings and skill mix in primary dental care: a pilot study

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

General dental practices with and without a dental therapist: a survey of appointment activities and patient satisfaction with their care

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Clinical leadership and prevention in practice: is a needs led preventive approach to the delivery of care to improve quality, outcomes and value in primary dental care practice a realistic concept?

BMC Oral Health (2015)

-

Alternative scenarios: harnessing mid-level providers and evidence-based practice in primary dental care in England through operational research

Human Resources for Health (2015)

-

Systematic review of patient safety interventions in dentistry

BMC Oral Health (2015)