Abstract

Study design:

Psychometric study.

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to examine the reliability of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III (SCIM III) by interview and compare the findings with those of assessment by observation.

Setting:

This study was conducted at Loewenstein Rehabilitation Hospital, Israel.

Methods:

Thirty-five spinal cord lesion (SCL) patients who underwent rehabilitation at Loewenstein Rehabilitation Hospital in Israel were assessed during the last week before discharge with SCIM III by observation and by interview. Nineteen of the patients were also assessed by interview by a third rater to examine inter-rater reliability. Total agreement, kappa, Bland–Altman plots and intraclass correlation (ICC) were used for comparison between interviewers and between interviews and observations.

Results:

Total agreement between the interviewers' scores and between interviews and observations was low to moderate (kappa coefficient 0.11–0.80). Bland–Altman analysis revealed good agreement, with low mean difference for almost all SCIM III subscales and total scores, between pairs of interviewers (bias −4.15, limits of agreement −22.51 to 14.19, for total score) and between interviews and observations (bias 1.62, limits of agreement −20.55 to 23.81, for total score). ICC coefficients for the SCIM III subscales and total scores were high (0.637–0.916).

Conclusion:

The findings of this study support the reliability and validity of SCIM III by interview, which appears to be useful for research of SCL patient groups. Individual scoring of SCIM III by interview, however, varied prominently between raters. Therefore, SCIM III by interview should be used with caution for clinical purposes, probably by raters whose scoring deviation, in relation to observation scores, is known.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM) is a scale for the assessment of achievements of daily function of patients with spinal cord lesions (SCLs). The third version (SCIM III) contains 19 tasks organized in 3 subscales: self-care, respiration and sphincter management, and mobility. The first and second versions of SCIM were introduced following studies performed in Israel.1, 2, 3 The psychometric properties of SCIM III were examined in a broad international study.4, 5 Further support for the reliability and validity of the scale was provided by a multicenter study in the United States.6 Both studies recruited large samples and demonstrated the usability of SCIM III assessment by observation of patient performance. SCIM III was recognized as the best available comprehensive SCL-specific functional status measure.7, 8 The instrument is widely used, and many professionals who implemented SCIM III in their clinics have provided positive feedback.

Many professionals, however, have showed interest in using the scale by interview rather than by observation, despite a general agreement that assessment by observation of patient performance is more accurate than by interview or questionnaire. Each method, however, has its advantages and disadvantages. Myers et al.9 stated that performance tests represent an isolated instance of a given behavior and may not reflect how a person carries out an activity usually. Neither do they reflect adaptations that a person uses in everyday life. At the same time, assessment by questionnaires or by interview may raise difficulties and may not be suitable, for example, for patients with cognitive deficits or for those who are illiterate.9

Functional assessment based on observation is considered to be more objective, standardized and quantifiable than assessment by self-report or by interview.9 Observation, however, is time-consuming and applicable mainly to inpatient populations,10, 11 whereas functional assessment based on self-report and interview requires relatively few resources, allows rapid data collection for research purposes and can be useful in both inpatient and outpatient environments.12

A study comparing SCIM II assessments by interview and observation showed moderate-to-good reliability and acceptable results, indicating that SCIM II can be used by interview.12 The ability to use SCIM III by interview is particularly important, because SCIM III is being used in many SCL units, some of which may lack optimal conditions for observation.6 SCL patients may require life-long follow-up after discharge from rehabilitation hospital, and an interview version of SCIM III can help professionals interacting with this population to evaluate their functional status at home, in outpatient clinics and other settings.

The present study examines the reliability of SCIM III assessment by interview and compares it with SCIM III assessment by observation.

Methods

Participants

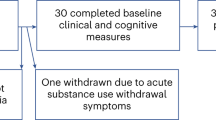

Thirty-five patients with SCL, who underwent rehabilitation for at least 1 month at the spinal rehabilitation department of Loewenstein Rehabilitation Hospital during the years 2008–2012, were included in the study (see Table 1 for patient characteristics). Patients were assessed with SCIM III (Hebrew version) by observation and by interview. Inclusion criteria were: SCL with American Spinal Injury Assessment Impairment Scale grade of A, B, C or D, age >18 years, proficiency in understanding and speaking Hebrew, and no concomitant impairment that might influence everyday function or verbal expression (such as brain damage or mental disease).

Procedure

We started data collection following approval of the ethics committee of Loewenstein Rehabilitation Hospital. Patients who met the study criteria were interviewed with SCIM III during the last week before discharge. Interviewers completed the regular SCIM III form according to their interpretation of the patients' responses as patients were discussing each task with the interviewer. All patients were interviewed in the course of the study by the same occupational therapist (OT), and 19 patients were also interviewed by one of two physiotherapists (PT), chosen randomly. The OT and PTs were experienced in functional assessment of patients with SCL but were not part of the team that treated the participants in the study and therefore were blind to the patients' abilities and function in everyday life. During the same time interval, patients were also assessed by one of the nurses who were caring for the patient using SCIM III by observation. Each of the raters performed the assessment independently and was blind to the scores of the other raters.

Data analysis

To assess the reliability of SCIM III by interview and to compare assessments by interview and observation, we: (a) examined the total agreement and the chance-corrected measure of agreement (unweighted kappa) for SCIM III tasks between the scores of the two interviewers and between the interviews and the observations, which were not continuous. The kappa values ranged between 0 (no agreement) and 1 (perfect agreement), and values of 0.6–1 were considered acceptable;13 (b) used an Bland–Altman plot to evaluate the agreement between interviewers and between interview and observation by assessing the distribution of the mean difference between the compared SCIM III subscales and total scores (mean differences, which are distributed mostly between 0 and 2 s.d. of the mean (limits of agreement), are considered to indicate acceptable agreement);14 and (c) examined the intraclass correlation (ICC) of the scores of SCIM III subscales and total scores, as assessed by the two interviewers or by interview and observation, which can be considered continuous. ICC estimated the proportion of variability between patients within the total variability in scores.15 ICC values >0.6 indicated good agreement and >0.75 indicated excellent agreement.16 Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0 (Armonk, NY, USA).

Statement of ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and government regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed in the course of this research.

Results

Interview and observation SCIM III scores

The range of SCIM scores was 25–97 (mean 62.2) for the first interviewer, 34–93 (mean 61.4) for the second interviewer and 39–95 (mean 64.1) for the observer.

Inter-rater reliability of SCIM III by interview

Total agreement between interviewers' scores was moderate for most SCIM III tasks (32–100%), with kappa coefficient values of 0.11–0.80, lowest for dressing, mobility in bed and mobility outdoors (detailed values and confidence intervals in Table 2). However, in 100% of the patients the SCIM III score difference between interviewers was only one point in almost half the tasks (Table 2). Bland–Altman plots show that the mean differences between interviewers' scores (bias) were very small or near zero and that the limits of agreement (reflecting the range of score difference between raters) were relatively low, with only few outliers (Table 3, Figure 1). ICC coefficients of the SCIM III subscales and total scores assessed by interview were high (0.88 for the total SCIM III score; Table 3).

Comparison between assessment by interview and observation

Total agreement between OT scores by interview and observer scores was low to moderate for most SCIM III tasks (17–100%), with kappa coefficient values of 0.1–0.7, lowest for dressing and use of toilet (detailed values and confidence intervals in Table 4). In 90–100% of the patients, SCIM III score difference was only 1 point in almost half the tasks (Table 4). Bland–Altman analyses comparing interview and observation revealed low bias and limits of agreement, with a small number of outliers (Table 3, Figure 2). The ICC coefficients of SCIM III subscales and total scores, assessed by interview and observation, were high (0.905 for the total SCIM III score; Table 3).

Discussion

The findings of the present study, including the low mean differences between the compared scores of the raters demonstrated by the Bland–Altman analysis, the high ICC for pairs of interviewers and for interviews and observations and the only one-point difference between compared scores in almost half the tasks, support the reliability and criterion validity of SCIM III by interview for the assessment of patient groups. But the low-to-moderate total agreement between interviewers and between interviews and observations indicates that SCIM III interview scores may be frequently inaccurate in individual assessments.

The lower total agreement in the current study than in the SCIM II by interview study may be explained by several methodological differences between the studies. In the present study, the sample used to compare interviews with observations was larger (35 vs 28), but the number of patients who were interviewed by two raters was smaller (only 19 vs 28), the patients examined were older and most of the patients had non-traumatic SCL. The most prominent difference between the studies was in the raters’ disciplines: in the present study, observations were conducted by a nurse, whereas in the SCIM II study they were carried out by a multidisciplinary team, and in the present study the interviews were conducted by an OT and PTs, whereas in the SCIM II study they were conducted by two nurses.12

The SCIM II by interview study showed that variation between individual assessments may be minimal when comparing the assessments of raters of the same profession; the findings of the present study show that interview assessments of the same patients by raters from different disciplines may vary considerably.12 Similar differences between scoring by professionals of different disciplines were found in a study comparing observational SCIM II scores of a single nurse with performance scored by a team. Despite the differences, the study concluded that the scoring of a single nurse may prove reliable and valid, if discrepancies are detected and corrected.17 It follows that using interviewers whose scoring deviation is known to assess individual patients can minimize inaccuracies in individual assessments of SCIM III by interview. If a rater's interview scores, assessed before the study, are consistently higher or lower than observation scores, assessed close to the interview, it is possible to detect scoring deviations, calculate their central value for each task and use it to correct the task score.

The possibility of such correction, combined with the reliability and validity found for group assessment and the use of the original (more informative and previously validated) SCIM III form, make SCIM III by interview a better option than the current self-reported SCIM III versions for assessments of SCL patients' daily task performance. It is a better option for individual assessments, because the correction of the scoring deviation that can be applied to the interview version cannot be applied to the self-reported versions of SCIM III, which have not been tested for total agreement between raters, and the accuracy of which in assessing the daily performance of individual SCL patients for clinical purposes is therefore unknown.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Both versions were found reliable for group assessment, and the use of the original SCIM III form in the interview version is an additional advantage of the interview version, because it assesses some important tasks that the self-reported SCIM III versions in current use fail to properly assess. This applies, for example, to the bladder management item, which can be assessed accurately in many patients instructed to follow their bladder capacity and residual urine volume, either by measurements of voided urine before and after intermittent catheterization or by ultrasound examination, performed at the clinic from time to time. Note that, in addition to its contribution to functional assessment, inquiring routinely about bladder volumes during functional assessment is of great importance for patient education and care.

The literature comparing assessment of SCL patients by interview and observation is scarce. Young et al.24 compared interview and observation assessments using the Functional Independence Measure in elderly patients after hip fractures at discharge from postacute rehabilitation. The authors also found adequate correlations in most tasks, but correlation was poor in dressing lower body, grooming and bladder management. By contrast, in the present study the poor correlations were in mobility outdoors, dressing upper body and use of toilet.24

It may be possible to improve the reliability of the interview by using an adapted SCIM III form, in which questions have been reformulated in interview style, to ensure that different interviewers pose the questions in the same way. However, we preferred each reviewer's interpretation to the regular SCIM III form, because identical phrasing of the questions does not guarantee identical understanding on the part of various patients and therefore does not guarantee the validity of the scores. Indeed, interpretation by an experienced professional may be necessary to ensure good understanding of the items and to obtain the most accurate and valid answers.

The availability of suitable PTs for continuous participation in the study was limited by the need to find raters who were experienced in functional assessment of patients with SCL and who were not part of the team that treated the participants (the latter was necessary to blind interviewers to the patients' abilities and function during the interview). This circumstance prolonged the study and resulted in a small convenience sample, despite the relatively long study period. The small sample, which included relatively old, many non-traumatic and American Spinal Injury Assessment Impairment Scale grade D SCL patients, is a drawback of the study and limits the generalizability of the findings. The SCIM III criteria relevant for younger patients with traumatic and severe SCL may be different from those relevant to the majority of the study population, and therefore the findings may not apply to younger patients. Finally, average time from injury was 3 years, and although it was less than a year for almost half the patients, findings may not be applicable for the early acute phase following traumatic SCL.

Conclusion

Findings support the reliability and validity of SCIM III by interview, which appears to be useful and more accurate than self-reported SCIM III scores, for the assessment of daily performances in research of SCL patient groups. However, individual scoring with SCIM III by interview may vary prominently between raters; therefore, it should be used cautiously in the assessment of individual SCL patients in clinical settings, preferably by raters whose scoring deviation, in relation to observational scores, is known.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A . SCIM-spinal cord independence measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 850–856.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Steinberg F, Philo O, Ring H, Ronen J et al. The Catz-Itzkovich SCIM: a revised version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure. Disabil Rehabil 2001; 23: 263–268.

Itzkovich M, Tripolski M, Zeilig G, Ring H, Rosentul N, Ronen J et al. Rasch analysis of the Catz-Itzkovich spinal cord independence measure. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 396–407.

Itzkovich M, Gelernter I, Biering-Sorensen F, Weeks C, Laramee MT, Craven BC et al. The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM) version III: reliability and validity in a multi-center international study. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1926–1933.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Tesio L, Biering-Sorensen F, Weeks C, Laramee MT et al. A multicenter international study on the Spinal Cord Independence Measure, version III: Rasch psychometric validation. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 275–291.

Anderson KD, Acuff ME, Arp BG, Backus D, Chun S, Fisher K et al. United States (US) multi-center study to assess the validity and reliability of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 880–885.

Anderson K, Aito S, Atkins M, Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, Curt A et al. Functional recovery measures for spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. J Spinal Cord Med 2008; 31: 133–144.

Post MW, Brinkhof MW, von Elm E, Boldt C, Brach M, Fekete C et al. Design of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 90: S5–S16.

Myers AM, Holliday PJ, Harvey KA, Hutchinson KS . Functional performance measures: are they superior to self-assessments? J Gerontol 1993; 48: M196–M206.

Dorevitch M . The 'questionnaire' versus the 'direct observation' approach to functional assessment. Br J Rheumatol 1988; 27: 326–327.

Hoenig H, Branch LG, McIntyre L, Hoff J, Horner RD . The validity in persons with spinal cord injury of a self-reported functional measure derived from the functional independence measure. Spine 1999; 24: 539–543.

Itzkovich M, Tamir A, Philo O, Steinberg F, Ronen J, Spasser R et al. Reliability of the Catz-Itzkovich Spinal Cord Independence Measure assessment by interview and comparison with observation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2003; 82: 267–272.

McHugh ML . Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 2012; 22: 276–282.

Bland JM, Altman DG . Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 327: 307–310.

McDowell I, Neweell C . Measuring Health: a Guide to Rting Scales and Questionnaires. Oxford University Press. 1987.

Cicchetti DV . Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess 1994; 6: 284–290.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Steinberg F, Philo O, Ring H, Ronen J et al. Disability assessment by a single rater or a team: a comparative study with the Catz-Itzkovich Spinal Cord Independence Measure. J Rehabil Med 2002; 34: 226–230.

Fekete C, Eriks-Hoogland I, Baumberger M, Catz A, Itzkovich M, Luthi H et al. Development and validation of a self-report version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 40–47.

Prodinger B, Ballert CS, Brinkhof MW, Tennant A, Post MW . Metric properties of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure—Self Report in a community survey. J Rehabil Med 2016; 48: 149–164.

Michailidou C, Marston L, De Souza LH . Translation into Greek and initial validity and reliability testing of a modified version of the SCIM III, in both English and Greek, for self-use. Disabil Rehabil 2016; 38: 180–188.

Bonavita J, Torre M, China S, Bressi F, Bonatti E, Capirossi R et al. Validation of the Italian version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III) Self-Report. Spinal Cord 2016; 54: 553–560.

Aguilar-Rodriguez M, Pena-Paches L, Grao-Castellote C, Torralba-Collados F, Hervas-Marin D, Giner-Pascual M . Adaptation and validation of the Spanish self-report version of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord 2015; 53: 451–454.

Mulcahey MJ, Calhoun CL, Sinko R, Kelly EH, Vogel LC . The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM)-III self report for youth. Spinal Cord 2016; 54: 204–212.

Young Y, Fan MY, Hebel JR, Boult C . Concurrent validity of administering the functional independence measure (FIM) instrument by interview. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009; 88: 766–770.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by a Legacy Foundation grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Itzkovich, M., Shefler, H., Front, L. et al. SCIM III (Spinal Cord Independence Measure version III): reliability of assessment by interview and comparison with assessment by observation. Spinal Cord 56, 46–51 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.97

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.97

This article is cited by

-

Definitions of recovery and reintegration across the first year: A qualitative study of perspectives of persons with spinal cord injury and caregivers

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

The relationship between balance control and thigh muscle strength and muscle activity in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2024)

-

Virtual rehabilitation for patients with osteoporosis or other musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review

Virtual Reality (2024)

-

Functional electrical stimulation therapy for upper extremity rehabilitation following spinal cord injury: a pilot study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2023)

-

Standardized administration and scoring guidelines for the Spinal Cord Independence Measure Version 3.0 (SCIM-III)

Spinal Cord (2023)