Abstract

Study design:

One-week retest methodological study.

Objectives:

To assess the reliability and validity of the wheelchair outcome measure (WhOM) in a sample of individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Methods:

The WhOM measures the impact of wheelchair interventions on a user's self-selected participation outcomes. The WhOM was administered to 50 participants on two occasions by the same rater, 1 week apart, to assess test-retest reliability. To determine inter-rater reliability, the WhOM was administered a third time approximately 72 h later by a different rater. Validity was evaluated by correlating scores from the WhOM with scores from the Assessment of Life Habits (LIFE-H).

Results:

The test-retest intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC2, 2) for the WhOM satisfaction (Sat) and WhOM importance (Impt) × Sat scores were 0.83 (95% confidence interval (CI), 0.72–0.90) and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.79–0.93), respectively. The inter-rater ICC for the WhOM Sat and WhOM Impt × Sat scores were 0.91 (95% CI, 0.85–0.95) and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.83–0.94), respectively. As hypothesized, most scores on the WhOM were fair to moderate (r=0.3–0.5) and positively correlated with scores on the LIFE-H.

Conclusion:

The WhOM is a new outcome measure that demonstrates good reliability and validity among individuals with SCI. It is designed to assist wheelchair users identify and evaluate the impact of wheelchair interventions on participation level outcomes. The WhOM may be applicable for clinical- or research-oriented purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) rely on wheelchairs as their primary means of mobility.1 Although these devices are provided to enable performance of social and daily activities, wheelchairs may also act as barriers to participation.2 Wheelchair prescription requires careful consideration of an individual's abilities, personal environment, and the activities he or she undertakes. Kittel et al.,3 found that through active engagement in the prescription process, users are more likely to retain and to use their wheelchairs.

Participation, defined as the extent of involvement in life situations given the individual's context (for example, impairments, activities, health conditions, personal and environmental factors),4 is considered a central goal for people with SCI.5 Determining the outcome of interventions designed to improve participation of wheelchair users provides critical feedback to clients, therapists and agencies that provide funding for equipment. As participation reflects the fulfillment of personal roles,6 individual identification and appraisal of participation outcomes is critical.7

A number of measures exist that provide information regarding a range of wheelchair-oriented outcomes; however, the majority of these do not measure outcomes at the level of participation and only one enables identification of participation outcomes that are important to the individual.8

The wheelchair outcome measure (WhOM) is a semistructured outcome measure that requires individuals to identify and rate their satisfaction (Sat) level with participation activities performed while using their wheelchair.9 The purpose of this study was to validate the WhOM for the SCI population. Specifically, we provide evidence of the test-retest reliability, inter-reliability, standard error of measurement (s.e.m.), minimal detectable difference (MDD), item agreement, and construct validity of the WhOM.

Methods

Design and sample

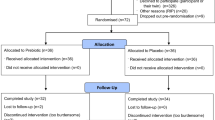

This one-week retest methodological study used a volunteer sample of 50 community living individuals with SCI who use a wheelchair. We recruited potential participants from our research participant database and occupational and physical therapist caseloads. Interested individuals were included if they (1) were aged 20 years or older; (2) used a wheelchair as their primary means for mobility (at least 4 h each day); (3) had a diagnosis of SCI; (4) were able to communicate in English; and (5) scored above 24 on the Cognitive Competency Screening Evaluation.10 We excluded individuals who had received a new wheelchair within the past 6 months. An a priori sample size of 50 was determined to be necessary on the basis of testing of the hypothesis11 that the intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficient was ⩾0.80 (α=0.05 and β=0.20) and to determine statistically significant correlations of r>0.35 (α=0.05 and β=0.20) when assessing validity.12

Measurement

The WhOM, developed using the international classification of functioning disability and health4 as a conceptual framework, is a client-centered, semistructured interview designed to identify individualized participation outcomes. Clients are asked standardized open-ended questions to identify the type of participation outcomes they perform inside and outside the home/community and then they rank the importance (Impt) of each one (0=no Impt, 10=very important). Next, they rank their level of Sat with performance (0=not satisfied at all, 10=extremely satisfied). Several summary scores can be obtained. Two WhOM scores were assessed in this study. The first score was the mean Sat (MeanSat), which represents the overall mean of the Sat rankings (score range=0–10). The second was the mean Impt (MeanImpt × Sat), which is calculated by multiplying the Impt score by the associated Sat score and then dividing by the number of participation outcomes (score range=0–100). Research on a French–Canadian version of the WhOM with a sample of middle age and older power mobility users indicated good psychometric properties.13

The 69-item Assessment of Life Habits (LIFE-H) General Short Form (version 3.1)14 was used for validation purposes as it provides another method of measuring independence, Sat and accomplishment with daily and social activities. The LIFE-H is a conceptually well-developed scale that has been used in previous studies of individuals with SCI. We selected items from the community life, employment, fitness and recreation domains because these areas reflect social activities and are consistent with the construct of participation as defined by the international classification of functioning disability and health. Because the WhOM was designed to capture participation as defined by the international classification of functioning disability and health, we believed this would better enable assessment of validity. Only items exploring Sat (not level of independence) were used. Study participants were asked to rate their level of Sat on a 5-point scale (1=very dissatisfied, 5=very satisfied) with these activities. Support for the reliability and validity of this measure among individuals with SCI has been reported.14, 15

Protocol

Two occupational therapists with >5 years of wheelchair prescription experience were trained to use the WhOM. We collected data at three time points. At time 1, consenting participants provided demographic data (for example, sex, type of wheelchair, date of injury), WhOM and other validity data. The order of the measures was randomized to minimize the influence of order effects. Because individuals with SCI often have more than one wheelchair (for example, individuals with tetraplegia may have a power and manual wheelchair), they were asked to provide WhOM data based on the wheelchair they used the most. Approximately 1 week later, participants re-rated their Sat with previously identified participation activities with the time 1 rater. Finally, approximately 3 days later, a different rater independently completed the entire WhOM with each participant. The local Research Ethics Board approved the study.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report results for the sample. Statistical assumptions were assessed to ensure that they were not violated beyond the tolerance of the statistic.

We used ICC2,2 to assess the retest and inter-rater reliability of the MeanSat and MeanImpt × Sat scores. We hypothesized that both types of reliability would be ICC⩾0.80 on the basis of findings from one other study of reliability on the WhOM.13 A coefficient of this magnitude is considered to be good to excellent.12 We also calculated the s.e.m. defined as the standard error of repeated scores and the MDD95% defined as the amount of change necessary to indicate true difference in scores.12

In order to examine the level of agreement between raters for the participation outcomes identified, we first categorized the items into 10 broad categories of activities ranging from employment to active and passive leisure.16 Then, the category specific and overall chance corrected κ was calculated. We classified κ-values according to Landis and Koch17 and hypothesized that a moderate (κ>0.41) or better overall level of agreement would be obtained.

Spearman's correlation coefficients were derived for assessment of validity because the LIFE-H scores are ordinal in nature. As LIFE-H items may be reported as ‘not applicable,’ we used only items that had 30 or more subject responses. We hypothesized that the magnitude of the associations would be greater than ρ⩾0.35 between the MeanSat, and MeanImpt × Sat and LIFE-H scores. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). An α of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The average age of the primarily male participants was 43.7 years (s.d.=10.7). Most subjects had tetraplegia and most used a manual wheelchair (Table 1).

The descriptive and reliability coefficients for the WhOM scores are detailed in Table 2. The scores for the MeanSat and the MeanImpt × Sat scores were in the top one-third range of possible scores. No participants had a perfect MeanImpt × Sat score, but six individuals scored 90+ out of 100. In all, 2 participants reported perfect MeanSat scores and 13 scored ⩾9 out of 10.

The ICCs for all WhOM scores exceeded 0.80. The ICCs for the inter-rater reliability were both above 0.90, whereas the magnitude of the retest ICCs were slightly lower. The s.e.m. values were all relatively small (Table 2).

The number and level of agreement for the participation outcomes identified by each rater and the participants are presented in Table 3. κ-values vary from a low of 0.40 for shopping to a high of 0.88 for childcare. The majority fell within the moderate agreement level, whereas the overall κ=0.71 represents a substantial agreement (Table 3).

The Spearman's correlation coefficients for the WhOM and LIFE-H items ranged from a high of ρ=0.62 for ‘entering and moving around your area of occupation’ to a low of ρ=0.16 and the MeanImp × Sat score ‘going to cultural events’ item (Table 4). Of the 32 correlations, 24 supported our hypotheses. Six correlations were not of sufficient magnitude to reach statistical significance, the majority of these occurring in the area of recreation. An additional two correlations did not reach our hypothesized magnitude of ρ⩾0.35. In all, 13 of the correlations had a ρ⩾0.50, the majority of these correlations were with the MeanSat scores. Finally, the magnitude of the correlations with the MeanSat scores was greater than MeanImp × Sat scores for 16 of the 18 LIFE-H items (Table 4).

Discussion

In a recent review of measures that were specific for wheelchair users, the WhOM was identified as the only measure that could capture a broad spectrum of participation outcomes.8 However, as noted in the review, the WhOM requires population-specific validation. To date, only one published measurement study of the WhOM exists and it focuses on a broad cross-section of middle/older adults who use power mobility.13

Our sample had relatively ‘high’ scores on both the MeanSat and MeanImp × Sat WhOM scores. Although the mean scores of the sample are around the top 70% of the possible scores, less than 20% reported a maximum score on both of the WhOM scores, indicating that a ceiling effect is not present.18 However, 25% of the sample did report 9 or higher on the WhOM Sat scores. Higher scores were expected because we sampled individuals who were not having changes with their wheelchair systems; therefore, we believe this suggests that they would be satisfied with their participation when using their wheelchairs.

All of the coefficients derived in this study exceeded our hypothesized level of reliability. The inter-rater ICCs were excellent, whereas the retest ICCs were considered good.12 However, the lower bands of the 95% confidence interval (CI) were slightly below 0.80 for both of the WhOM retest ICCs. Although the retest MeanImpt × Sat score was just below the 0.80 parameter, the lower band of the 95% CI of the MeanSat was lower than the highest preferred level (ICC⩾0.75) for disability measures.18 It seems plausible that recall may explain this finding given 7 days separating retest reliability, whereas only 3 days separated the inter-rater reliability. Extending the period between testing can reduce memory bias; however, this increases the likelihood that variation in Sat will occur.12 Retest reliability coefficients were very similar to those for the French–Canadian version of the WhOM.13

The MDD95% coefficients provide information about the MDD. If a postintervention retest score exceeds the MDD95% value, we can be 95% certain that we have seen change that exceeds measurement error and therefore reflects a true difference.12 The MDD95% values are small, for instance, a 1.6-unit change on the WhOM Sat score would indicate real change. Although this value provides a minimal statistically important change, it does not necessarily indicate a ‘clinically’ important change.

Finding moderate or better agreement between raters on the identification of participation outcomes suggests that different clinicians and/or researchers can be relatively certain that similar participation outcomes will be identified. One plausible explanation for not obtaining higher κ as well as the difference in the number of outcomes identified is that the application of the WhOM by rater 1 may have caused a testing effect in which the participants reflected on their participation outcomes and Sat in greater detail over the testing period. An increased awareness may have led the participant to scrutinize their situation more closely and therefore lead to a different number of outcomes and rating of their Sat. Guyatt et al.19 suggest that allowing clients the opportunity to see their baseline responses insures reliability while not interfering with the responsiveness of the measure. Therefore, clinicians may want to provide the previous information collected on the WhOM before collecting follow-up data after intervention. Data from future studies of the responsiveness of the WhOM will validate the use of this approach.

Support for validity was demonstrated by the magnitude and direction of the majority of correlations between the level of Sat with selected items from the LIFE-H and the WhOM scores. Although recreation correlations tend to be lowest, this may also reflect decreased variability in these items on the LIFE-H. Interestingly, Noreau and Fougeyrollas20 found that recreation was one of the most disrupted life habits among individuals with SCI. As anticipated, specific questions from the Sat scale of the LIFE-H that are related to getting into or going to participation-oriented outcomes demonstrated fair–to-moderate correlations with the WhOM. This finding seems to confirm that the wheelchair is clearly important as a mobility device that facilitates involvement in social activities. The magnitude of the relationships between the WhOM scores and the LIFE-H items that clearly measure participation such as items indicating Sat with involvement in relaxing, physically active and volunteer positions is also reassuring because it suggests strong convergence on the construct of interest.

The measurement of Impt represents a critical advantage for the WhOM over tools that do not assess this construct. Because almost all of the LIFE-H items were more strongly correlated with MeanSat rather than MeanImp × Sat scores, it may indicate that individuals who participated in these activities and were satisfied with their level of involvement may not deem them to be as important. This finding suggests that the measurement of Sat with performance that the client does not consider Impt may not capture the individualized nature of social participation. This may also explain why some of the MeanImp × Sat correlations were smaller than expected, because this score incorporates participant's ratings of Impt.

Limitations

A number of limitations may have affected the findings of this study. In terms of test-retest reliability, if the entire tool was readministrated, some of the results may have changed. Moreover, we would have been able to estimate the level of agreement in the participation outcomes within rater at retest. However, the procedure we chose is more similar to clinical practice and from that perspective adds ecological validity to our selected design. Furthermore, having the participants identify their participation activities at time 2 would have created additional recall bias, when the second rater readministered the WhOM in its entirety.

It is plausible that the time delay for the retest and inter-rater data collection was too short. A number of factors come into play when deciding on the ideal reapplication of a measurement tool, including providing enough time to limit recall from the previous assessment to making sure that real change in the construct of interest did not occur. The field of study assessing the Sat with performance of participation using the wheelchair is in its infancy. If Sat in performing participation-oriented activities is highly variable, short time periods of follow-up to reduce chance for real change may more be beneficial.

We used a volunteer sample, which consisted of a large number of individuals with tetraplegia. Therefore our sample does not reflect the general population of individuals with SCI. This fact should be acknowledged when generalizing to the larger population of individuals with SCI. A related generalizability issue is that many individuals have more than one wheelchair. Our clinical experience suggests that individuals do complete different activities using different wheelchairs. For instance, some individuals have a sports wheelchair for basketball and a more basic manual design for daily use, whereas others with a higher level of injury may have both a power and manual chair. In this study, we asked the subjects to complete the WhOM while thinking about participating in activities in the chair they most frequently use. Therefore, when using the WhOM, we suggest that clinicians and researchers insure that they are collecting device-specific information in those cases when multiple chairs are available to the individual with SCI.

We chose the LIFE-H for validation purposes on the basis of its strong conceptual foundations, ability to measure Sat with participation, and because it has been used in longitudinal studies of the SCI population. Another feature of the LIFE-H is that it enables participants to select ‘not applicable’ for items included in the tool. Although this response option is more ‘client-centered’, it provided a challenge for us because of the variation in responses to the individual items. Therefore, instead of providing correlations to areas of participation, we needed to correlate the WhOM scores with specific items because of considerable variation in response to each item. This may have influenced the magnitude of the correlations investigated in this study.

When scoring the WhOM various options are available. The MeanImpt × Sat score presents a weighting factor based on the client identifying how important the participation outcome is to them. Although this is a clinically appealing method to identify the most important client-centered outcomes, it may be problematic mathematically given that having high Sat with an unimportant outcome could lead to an equivalent score as having poor Sat with an important outcome. Ideally, the client would identify their top five outcomes that would enable the clinician to prioritize which areas to address. It is reassuring therefore to see that the reliability and validity coefficients are similar for the MeanSat scores. Therefore, we recommend that clinicians use the Impt factor to rank order outcomes that need to be addressed hierarchically and then use the Sat score to quantify the outcome.

Conclusion

The WhOM is a flexible, individual-specific measure of wheelchair-related participation. It requires the individual to contextualize his/her response on the basis of use of his/her wheelchair in his/her environments of choice. This feature potentially provides a more sensitive assessment for wheelchair interventions. The results provide support for the reliability and validity of the WhOM in the SCI population. Future studies to explore additional measurement metrics, such as responsiveness to change after intervention, are needed.

References

New PW . Functional outcomes and disability after nontraumatic spinal cord injury rehabilitation: results from a retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 250–261.

Mann WC, Hurren D, Charvat B . Problems with wheelchair experienced by frail elders. Technol Disabil 1996; 5: 101–111.

Kittel A, Di Marco A, Stewart H . Factors influencing the decision to abandon manual wheelchairs for three individuals with a spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2002; 24: 106–114.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2001.

Boschen KA, Miller WC, Noreau L, Wolfe DL, McColl MA, Martin-Ginis KA et al. Community reintegration following spinal cord injury. In: Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC (eds). Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence, Vol 2.0 ICORD: Vancouver, BC, 2008.

Cardol M, de Hoon RJ, de Jong BA, van den Bos GA, de Groot IJ . Psychometric properties of the impact on participation and autonomy questionnaire. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 210–216.

Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P, Post M, Asano M . Participation after spinal cord injury: the evolution of conceptualization and measurement. J Neurol Phys Ther 2005; 29: 147–156.

Mortenson WB, Miller WC, Auger C . Issues for the selection of wheelchair-specific activity and participation outcome measures: a review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: 1177–1186.

Mortenson WB, Miller WC, Miller-Polgar J . Measuring wheelchair intervention outcomes: development of the wheelchair outcome measure. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 2: 275–285.

Xu G, Meyer JS, Thornby J, Chowdhury M, Quach M . Screening for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) utilizing combined mini-mental-cognitive capacity examinations for identifying dementia prodromes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17: 1027–1033.

Donner A, Eliasziw M . Sample size requirements for reliability studies. Stat Med 1987; 6: 441–448.

Portney LG, Watkins MP . Foundations of clinical research applications to practice, 3rd edn. Prentice Hall Inc: NJ, 2009.

Auger C, Demers L, Gelinas I, Routhier R, Mortenson WB, Miller WC . Reliability and validity of telephone administration of the wheelchair outcome measure for middle-aged and older users of power mobility devices. J Rehabil Med 2010; 42: 574–581.

Noreau L, Desrosiers J, Robichaud L, Fougeyrollas P, Rochette A, Viscogliosi C . Measuring social participation: reliability of the LIFE-H in older adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 2004; 26: 346–352.

Desrosiers J, Noreau L, Robichaud L, Fougeyrollas P, Rochette A, Viscogliosi C . Validity of the assessment of life habits in older adults. J Rehabil Med 2004; 36: 177–182.

Juster FT, Stafford FP (eds). Time, Goods, and Well-Being. Institute for Social Research: MI, 1987.

Landis JR, Koch GG . The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–174.

Andresen EM . Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81 (Suppl 2): S15–S20.

Guyatt GH, Berman LB, Townsend M, Taylor DW . Should study subjects see their previous responses? J Chron Dis 1985; 38: 1003–1007.

Noureau L, Fougeyrollas P . Long-term consequences of spinal cord injury on social participation: the occurrence of handicap situations. Disabil Rehabil 2000; 22: 170–180.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by the British Columbia Neurotrauma Foundation. During the tenure of this grant, the Canadian Foundation of Health Institutes and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research provided salary support for Drs Miller and Mortenson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, W., Garden, J. & Mortenson, W. Measurement properties of the wheelchair outcome measure in individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 49, 995–1000 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.45

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.45

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Feasibility of the trial procedures for a randomized controlled trial of a community-based peer-led wheelchair training program for older adults

Pilot and Feasibility Studies (2018)

-

Feasibility of a Systematic, Comprehensive, One-to-One Training (SCOOT) program for new scooter users: study protocol for a randomized control trial

Trials (2017)