Abstract

While the spread of communicable diseases such as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is often analyzed assuming a well-mixed population, more realistic models distinguish between transmission within and between geographic regions. A disease can be eliminated if the region-to-region reproductive number—i.e., the average number of other regions to which a single infected region will transmit the disease—is reduced to less than one. Here we show that this region-to-region reproductive number is proportional to the travel rate between regions and exponential in the length of the time-delay before region-level control measures are imposed. If, on average, infected regions (including those that become re-infected in the future) impose social distancing measures shortly after experiencing community transmission, the number of infected regions, and thus the number of regions in which such measures are required, will exponentially decrease over time. Elimination will in this case be a stable fixed point even after the social distancing measures have been lifted from most of the regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in Wuhan, China, reportedly in December 20191 and has since become a severe pandemic2. Understanding the dynamics of disease transmission both within and between regions3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 can provide insight into how to eliminate the outbreak by imposing restrictive measures only where the virus is locally spreading, thus minimizing larger-scale economic impacts11,12,13,14. Regions could be cities, counties, states, or any other partition of a population such that the disease transmission occurs predominantly within (as opposed to between) regions. The choice of region size depends on the spatial granularity at which policy makers are willing and able to control disease transmission.

Since it is impossible to model all the details of real-world systems, identifying large-scale behaviors is necessary to determine which details matter and how15,16,17. For COVID-19, the parameters for these large-scale behaviors include the average size of an outbreak within a region and the transmissibility of the outbreak between regions. The values of these two parameters, both of which can be controlled with interventions, determine whether the behavior of the epidemic within a collection of regions (e.g., a country) is that of exponential spread until saturation (e.g., dynamic endemic equilibrium or herd immunity) or exponential decay until elimination. In the latter regime, elimination will be stable and most regions within the collection can fully open up their economies, with only local and sporadic social distancing measures needed to contain outbreaks arising from hidden or imported cases.

A central concept in the study of disease spread is the reproductive number R, i.e., the average number of people to whom a typical infected individual will transmit the disease18. To consider the transmission between regions, an analogous region-to-region reproductive number R* can be defined as the number of other regions (including those that have been previously infected) to which a single infected region will transmit the infection on average19,20. Just as an outbreak cannot sustainably propagate (i.e., elimination is stable) among individuals within a region if R < 1, an outbreak cannot sustainably propagate among regions within a collection if R* < 1.

Here, we analyze how local measures can support the elimination of COVID-19 while avoiding large-scale lockdowns where they are unnecessary. We find that reductions in travel and the speed with which regions act to contain future outbreaks play decisive roles in whether COVID-19 is eliminated from a collection of regions (i.e., whether R* < 1). Such an elimination is stable: for each outbreak caused by imported or undetected cases, only a few regions—fewer than 1/(1 − R*) on average—need to temporarily impose measures while the rest of the regions in the collection remain open. If infected regions (including those that become re-infected in the future) impose control measures shortly after experiencing community transmission (i.e., shortly after no longer being a “green zone”), the number of infected regions, and thus the number of regions in which such measures are required, will exponentially decrease over time.

Results

General model

The disease is modeled as being transmitted among individuals within a region, with travel allowing the disease to spread between regions. A collection of regions is defined as any partition of a population such that travel/social contact within each region far exceeds that between them (e.g. the U.S. could be partitioned by county or commuting zone boundaries), in order that an infected individual is far more likely to transmit the virus to someone within the same region rather than to someone in a different region (i.e. transmission between regions can be treated as a first-order perturbation). Policy makers are assumed to act homogeneously within each region and to have the ability to act independently between regions—thus, the choice of how to partition a population into regions must take into consideration the spatial granularity at which policy makers are willing and able to make decisions. Treating larger areas as single regions means that social distancing measures will be homogeneously applied to larger areas but also means that it is easier to achieve lower per capita travel rates between such areas.

We define a region as infected if someone with the infection enters the region. Community transmission, also known as community spread, is said to occur when individuals within a region are infected from an unknown source21. Conditioning on region c being infected, we let Nc be a random variable (that could be zero) denoting the total number of new infections that occur in region c from the time after the region is infected to the time at which there is no more community transmission, at which point we define the region as no longer infected. Let pc be the probability that an infected individual in region c will travel to another region during the period in which that individual is contagious. Then, the region-to-region reproductive number for region c—which we define as the expectation of the number of regions that region c will infect if it becomes infected—is \({R}_{* }^{c}={\mathbb{E}}[{N}_{c}]{p}_{c}\). The expected outbreak size \({\mathbb{E}}[{N}_{c}]\) can be greatly reduced if regions impose strong social distancing measures shortly after detecting community transmission (these social distancing measures can be lifted once community transmission has been contained), while pc can be reduced by reducing travel out of infected regions.

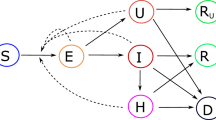

\({R}_{* }^{c}\) may differ from region to region, with \({R}_{* }^{c}\) for a particular region depending not only on internal factors but also on the network connectivity between that region and others, which in turn depends on the sizes of regions (i.e. the scale/level of granularity of the interventions). If the interventions are sufficiently fast and strong such that R*—the average value of \({R}_{* }^{c}\) over a collection of regions with each region weighted by its probability of being infected18—is less than one, then the outbreak will not be self-sustaining within that collection of regions. Put another way, a collection of regions can exist in one of two regimes: a regime for which elimination is a stable fixed point of the system and a regime for which it is unstable (see Fig. 1). A change in policy can shift a collection of regions from the unstable regime (R* > 1) to the stable regime (R* < 1) or vice versa. Although the values of Nc for a collection of regions could currently be high, R* is determined by \({\mathbb{E}}[{N}_{c}]\) and pc for the regions that will be infected or re-infected in the future after social distancing has eliminated the virus from currently infected regions.

Elimination can either be stable or unstable; the stability of elimination is a function of (1) the average total number of cases that will result from the disease being transmitted to a region (which depends on, among other factors, how quickly regions locally impose social distancing measures if they experience community transmission), and (2) the probability that an infected individual in one region will infect an individual in another (which depends on the rate of travel between regions). Note that the stable regime does not require that every region implement social distancing measures but rather only those with active community transmission. Thus, once elimination is achieved, it can be maintained while most regions remain economically open, with outbreaks caused by hidden or imported cases contained by social distancing measures that are localized in both space and time. Image source: ref. 25.

We note that if region c were infected multiple times, \({\mathbb{E}}[{N}_{c}]\) would be higher than if it were infected once, but it is assumed that infecting an already infected region will on average contribute no more to disease spread than infecting a currently uninfected region. Thus, like the basic reproductive number, this region-to-region reproductive number overestimates the disease spread away from the limit of most regions being uninfected by counting a single region that has been infected multiple times during a single outbreak as multiple regions being infected. To the extent that a region being infected multiple times has a linear effect on its expected total number of cases, this approximation will not impact the values of R*. However, if a region that is currently implementing control measures because of previous importations receives additional imported infections, these additional importations are not likely to have as large an effect as the previous ones that occurred before control measures were implemented. Thus, R* may be overestimated when a high total number of infections within a collection of regions makes it common for regions to experience multiple importations during a single outbreak. We also note that, as in SIS compartmental models, an infected region in which the virus is contained can later be re-infected.

It is important to keep in mind that a collection of regions can be in the stable regime, in which the region-to-region reproductive number for the collection R* is less than one, while, at any given time, the reproductive number R of most regions within the collection is greater than one. In other words, in order for R* < 1 for the collection of regions, individual regions within the collections need only maintain R < 1 so long as community transmission persists within them; otherwise, they can lift social distancing measures and open up economically. For every infection that a collection of regions with R* < 1 imports (not including cases that were quarantined at the border), the average number of regions within that collection that will need to impose social distancing measures is bounded by \(\alpha \mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{n = 0}^{\infty }{({R}_{* })}^{n}=\alpha /(1-{R}_{* })\) where α, which can be reduced with testing and contact tracing, is the probability that an imported case will result in community transmission within a region. Thus, border control need not be perfect; if a collection of regions has sufficiently good border control and policies that ensure R* < 1, elimination will remain stable while most of the collection’s regions remain open most of the time.

Modeling the approximate size of regional outbreaks

We now describe a simple mathematical model to estimate Nc, not to provide a precise description of the epidemic trajectory but rather to clarify how various interventions may affect outbreak size. This specific model assumes exponential growth before control measures are implemented followed by exponential decline afterwards. However, the validity of this assumption is not essential to the main results, which depend only on the number of infected individuals traveling out of each region. Modeling the number of active cases within a region using exponential growth and decay serves mainly to give a quantitative handle on the rates of increase and decrease in cases, but comparable results could be obtained using other epidemic trajectories. (Similarly, although SIS and SIR models assume an exponential distribution of generation intervals, this particular assumption does not affect the conditions under which such models are valid, so long as their recovery rate γ is treated as an effective parameter.) The one key assumption is that the reproductive number within individual regions can be reduced below one with sufficiently strong measures such as mask-wearing, social distancing, contact tracing, etc. This assumption has been validated empirically by the many regions around the world in which the number of cases has declined for a sustained period of time.

Let \({i}_{0}^{c}\) be a stochastic factor that roughly corresponds to the initial foothold that the virus gains in region c conditioning on an infected individual entering the region, with \({i}_{0}^{c}=0\) corresponding to the case in which no one was infected or a few people were infected but the outbreak was contained by contact tracing/quarantine or otherwise spread no further (e.g. no community transmission). The probability distribution of \({i}_{0}^{c}\) will depend on the distribution of infectiousness22, a function of both biological and social factors. If the outbreak is contained (\({i}_{0}^{c}=0\)), then the number of active infections remains at zero for the purposes of this model because—by definition—the outbreak has no chance of spreading to other regions.

If the outbreak is not contained (\({i}_{0}^{c}\, \ne \, 0\)), the number of active infections is modeled as growing with time t at an exponential rate \({e}^{{r}_{c}t}\). Then, after time Tc (the delay in response), the region implements social distancing measures that cause the number of active infections to decay as \({e}^{-t/{\tau }_{c}}\), where τc is the time-constant (i.e. the inverse of the rate) of decay. Such exponential decrease will occur if the social distancing measures, together with mask-wearing and testing/contact tracing/quarantine, can reduce the reproductive number (R) of the virus below one. The greater the reduction in R, the smaller the value of τc and thus the faster the decrease in infections. (For R < 1, R is related to τc by \(1=\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{\infty }Rg(t){e}^{t/{\tau }_{c}}dt\) where g(t) is the distribution of generation intervals23.) We note that this assumption of exponential increase followed by exponential decay after intervention assumes that the proportion of susceptible individuals is roughly constant, i.e. that the region intervenes before a significant fraction of its population is infected, which is the regime with which we are concerned. To the extent that this assumption does not hold, its use will result in an overestimate of the number of infected individuals and thus does not affect our main conclusions.

The number of active infections in region c as a function of time (see Fig. 2) can therefore be written as:

The number of active infections ic in a region c according to the model described by Eq. (1) are shown as a function of time. The time at which community transmission begins is defined as t = 0. At t = Tc (a duration of Tc after the start of community transmission), control measures that reduce the reproductive number of the virus to less than one are implemented. At t = Tc, the size of the outbreak is \({i}_{0}^{c}{e}^{{r}_{c}{T}_{c}}\) where \({i}_{0}^{c}\) is a stochastic factor and rc is the rate of exponential growth without the control measures. In order to eliminate the community transmission, we estimate that the control measures must remain in place for a duration of approximately \({\tau }_{c}({r}_{c}{T}_{c}+\mathrm{ln}\,{i}_{0}^{c})\) (see Eq. (2)), where \({\tau }_{c}^{-1}\) is the rate of exponential decay in the number of infections under the control measures. Thus, the longer the region waits to enact the measures, the longer the total amount of time they must remain in place.

The social distancing measures can be lifted once no active infections remain in the region or once there is no more community transmission and the remaining infections can be contained with contact tracing. Solving for ic(t) = 1 (assuming \({i}_{0}^{c} \, \ne \, 0\)) yields an approximate duration for the social distancing measures of

As the number of cases becomes increasingly small, testing and contact tracing become increasingly effective and can hasten the end of community transmission, thereby allowing the social distancing measures to be lifted. The probability that the number of infections will rebound after the social distancing measures are lifted—in which case an additional phase of such measures will be needed, as in the Imperial College report24—will depend on the probability of importation from other regions, which in turn will depend on the region-to-region reproductive number R*. Even though the virus can be re-imported, as long as R* < 1, the number of infected regions will on average decrease over time, since re-importation events are included in R*.

Modeling transmission between regions

Each infected region c infects a currently uninfected region with a probability rate proportional to the number of active infections ic(t) times the probability rate pc that an infected individual will travel to an uninfected region. The number of new infected regions spawned by region c can thus be modeled as a Poisson process with rate ic(t)pc. As described above, this modeling assumption overestimates the spread of the disease to new regions by counting a single new region that has been infected multiple times (possibly by multiple other regions) as multiple new infected regions. The smaller the number of regions infected and the smaller the probability of one region infecting another, the smaller the probability that the same region will be infected twice. Nonetheless, for certain regional connectivity networks, this model may overestimate R*. (Our main conclusions are unaffected because R* will be less than one if its overestimate is.)

Let \({p}_{0}^{c}\) be the per capita probability rate before time Tc of individuals in region c traveling to other regions and \({p}_{1}^{c}\) be the probability rate afterwards (\({p}_{1}^{c}\) will be less than \({p}_{0}^{c}\) if travel is discouraged and/or restricted at the time social distancing measures are implemented). The number of new regions that are infected by region c will then be a Poisson random variable with a mean of

Taking the expected value over \({i}_{0}^{c}\) (and allowing for a slight overestimate of \({R}_{* }^{c}\) by treating the \(\frac{1}{{i}_{0}^{c}}\) term as negligible when \({i}_{0}^{c}\, > \, 0\)) yields

(The value of R* for a collection of regions is then an appropriately weighted average of \({R}_{* }^{c}\) over that collection, as described above.)

Estimating R* for COVID-19

In order to better understand the extent of the measures required to achieve R* < 1, we estimate the values of the parameters in Eq. (5) (see Fig. 3 and Methods) in order to determine \({R}_{* }^{c}\) as a function of the time-delay before social distancing measures are enacted, as shown in Fig. 4. Note that the time-delay is measured from the time at which exponential growth begins to occur—which could be as early as the beginning of community transmission within the region—not the time at which exponential growth is first measured. The latter may lag the former due to delays in testing and the possibility of pre-symptomatic/asymptomatic spread.

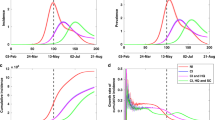

a The daily number of confirmed cases in China—by date that these patients self-reported as the onset of their symptoms—are shown as dots on a logarithmic scale. The solid lines are the best ordinary least squares linear fits to the natural logarithm of the number of cases: For Jan. 11-23 (up until the lockdown), the slope (in units of day−1) is 0.228 (R2 = 0.991, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.214, 0.242]), which corresponds to a doubling time of 3.04 days. For Feb. 2-5 the slope is −0.145 (R2 = 0.999, 95% CI [−0.160, −0.131]), which corresponds to a halving time of 4.78 days. Data are from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention38, which includes cases diagnosed through Feb. 11. Not pictured: There is a drop in cases with onsets of symptoms after Feb. 538, likely due to many of those cases being diagnosed after Feb. 11. b The daily number of confirmed cases in Italy by date of symptom onset are shown as dots on a logarithmic scale (data are from Italian authorities47). The best ordinary least squares linear fits are shown as solid lines and have slopes (in units of day−1) of 0.262 (R2 = 0.927, 95% CI [0.202, 0.322]) for Feb. 16-25, 0.123 (R2 = 0.923, 95% CI [0.102, 0.144]) for Feb. 25 - Mar. 10, and −0.068 (R2 = 0.901, 95% CI [−0.078, −0.058]) for Mar. 13 - Apr. 5. The change in the exponential growth rate from 0.262 to 0.123 likely occurred due to partial measures implemented by Italy, but it was not until a nationwide lockdown was implemented on March 9 that exponential growth changed to exponential decline. The rate of decline is much slower in Italy than in China, perhaps due to China’s stronger lockdown enforcement and contact tracing/quarantine measures.

Each curve depicts, under different travel policies, the average number of regions \({R}_{* }^{c}\) to which region c will transmit the disease as a function of the time delay Tc between when region c experiences community transmission and when it imposes social distancing measures (Eq. (5)). If the region-to-region reproductive number R* (a weighted average of \({R}_{* }^{c}\) over a collection of regions) is less than one, the number of infected regions will exponentially decrease and the elimination of the disease within that collection of regions will be stable; otherwise, the number of infected regions will increase until saturation. Parameter values: All curves use average initial foothold \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}]=3.7\), inverse exponential decline rate τc = 15 days, and exponential growth rate rc = 0.228 day−1. Solid curve: no travel reduction; the per capita travel rates out of region c before and after Tc are, respectively, \({p}_{0}^{c}={p}_{1}^{c}=0.004\) day−1. Dashed curve: 10-fold (responsive) travel reduction after time Tc; \({p}_{0}^{c}=0.004\) day−1 and \({p}_{1}^{c}=0.0004\) day−1. Dotted curve: general (preemptive) 10-fold travel reduction; \({p}_{0}^{c}={p}_{1}^{c}=0.0004\) day−1. Note that some of these parameter estimates are conservative and are likely to overestimate \({R}_{* }^{c}\) as a function of Tc—see Methods for discussion.

Discussion

Our analysis and parameter estimates are conservative and are therefore likely to overestimate R*, meaning that there may be more room for error than Fig. 4 suggests. However, given the considerable uncertainty surrounding pandemics and the impossibility of precisely predicting their trajectories25, R* should be reduced as much as possible so as not to take any chances, as well as so that the virus will be eliminated (and economies more fully reopen) as quickly as possible. Since R* is proportional to both \({\mathbb{E}}[{N}_{c}]\) and the travel rates between regions, any intervention that reduces the sizes of outbreaks within regions and/or travel between them will also reduce R*. In the language of Eq. (5) (see Table 1):

-

A reduction in travel from region c results in a linear reduction in \({R}_{* }^{c}\) through \({p}_{0}^{c}\) and \({p}_{1}^{c}\).

-

Improvements in testing, contact tracing, and quarantine reduce \({R}_{* }^{c}\) through \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}]\), rc, and τc.

-

Preemptive measures (i.e. measures before Tc, including when no spreading has been detected) such as mask-wearing and the reduction of large gatherings reduces the probability of a super-spreader event as well as general transmission, reducing \({R}_{* }^{c}\) through both \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}]\) and rc. Because—in the absence of interventions—a small fraction of COVID-19 cases cause most of the spread26,27, the reduction of super-spreader events can have an outsized impact.

-

Reductions in rcTc not only exponentially reduce \({R}_{* }^{c}\) (as well as the total number of infections within the region) but also linearly reduce the amount of time for which the social distancing measures must remain in place. Early-detection systems28,29 and more comprehensive testing may greatly reduce Tc.

-

Stronger social distancing measures (after time Tc) decrease τc, which results in a linear decrease in both \({R}_{* }^{c}\) and the time for which the distancing measures must remain in place.

We conclude with a few comments. First, without the timely implementation of control measures that reduce the local reproductive number to less than one, restricting travel from infected regions serves only to delay the spread of the outbreak, as found in other studies30,31,32,33,34,35,36. However, when a reduction in travel is coupled with such measures, the travel reduction will not only delay the spread of the outbreak but in some cases will also be the determining factor in whether or not the outbreak is eliminated. (If R* < 1 can be achieved without reducing travel, travel reductions can greatly decrease the duration and total case count of the epidemic by further reducing R*.) Empirically, travel restrictions, when combined with other sufficiently strong interventions, have been found to substantially curb the COVID-19 epidemic37.

Second, because \({R}_{* }^{c}\) depends exponentially on Tc, the longer a region waits to implement social distancing measures, the more important it becomes to act without delay. It is important to note, however, that there is no advantage to delaying for even a short time. Immediately implementing social distancing measures as soon as there is evidence of the disease spreading within the region will not only reduce the total amount of time for which such measures must remain in place but will also exponentially reduce the probability of infecting or re-infecting another region. Thus, there is no tradeoff here between health and economics—acting quickly will reduce the duration of both the disease and the economic harm.

Third, practically speaking, all regions within which the virus is spreading must implement and maintain control measures that reduce the local reproductive number to less than one until the virus has been eliminated or contained. If a locale experiences another outbreak of community transmission (e.g. because the virus was re-imported), sufficiently strong interventions should be implemented in a large enough region around that locale so that the per capita rate of travel out of the region is sufficiently low. Per capita travel rates between regions do not have to be zero, but they must be small—precisely how small depends on the parameters in Eq. (5). In the event that some regions “defect” by not containing their outbreaks (thereby putting other regions at risk), other regions must either quarantine travelers from those regions or maintain precautions that keep their local reproductive numbers below one to avoid further outbreaks. Due to the higher rates of travel between neighboring regions, extra precautions are necessary in a region that has a neighbor with widespread disease transmission.

Finally, like transmission within a region, transmission between regions is an exponential process. At first the number of infected regions is deceptively small, but if R* > 1, this number exponentially grows. If, however, a collection of regions adopts a set of protocols that achieves R* < 1, sustained propagation of the disease between the regions will not be possible, and future outbreaks caused by importations will die out while leaving most regions within the collection unaffected.

Methods

Estimating COVID-19 parameters

The doubling time of the epidemic can vary from location to location and depends on pre-lockdown interventions (see e.g. the change in the growth rate for Italy in Fig. 3). Using the number of confirmed cases in China by date of symptom onset (rather than by date of diagnosis)38 yields a doubling time of 3.04 days in the period leading up to the Jan. 23 lockdown, which corresponds to rc = 0.228 day−1 (Fig. 3). Some studies estimated the doubling time for COVID-19 at approximately 7 days39,40, but even a 5-day doubling period is implausibly long, given that in various countries, even with some preventative measures, the number of infections increased by far more than a factor of 64 over a 30 day period41. Part of the difficulty in estimating the doubling time from the initial period of transmission is that ‘super-spreader’ events may play an important role in the transmission process22,26,27. The presence of super-spreader events indicates that the transmission process may be dominated by relatively uncommon events and that therefore standard statistical approaches may underestimate the rate of spread—and thus overestimate the doubling time—when the total number of cases is still small42. (Overestimates of the doubling time lead to underestimates of R0.) Furthermore, due to heterogeneity from both social and biological factors in transmission rates among various subgroups in a population, the expected growth rate in the very earliest phase of an epidemic depends on the subgroups in which the disease is initially introduced and may not be reflective of the true reproductive number18.

While ic(t) is equal to the number of active infections rather than the daily number of new cases, the doubling time for each will be equal during a period of exponential growth, and therefore the exponential rate of growth of the daily number of new cases can be used to estimate rc. We note that a doubling time of 3 days will likely be a substantial overestimate for regions that, even when cleared of the virus, still maintain some precautionary measures such as mask-wearing, working from home when possible, and avoiding large gatherings.

From this growth rate r = 0.228 day−1 in China before the Jan. 23 lockdown, the basic reproductive number R0 (which also varies by location and time) can be calculated for China before Jan. 23 using

where g(t) is the distribution of generation intervals23. Empirically, we generally observe the distribution of serial intervals (the times between the onsets of symptoms in two successive cases in a transmission chain) rather than the distribution of generation intervals (the times between two successive infections in a transmission chain)43. The means of the two distributions will, however, be the same. The distribution of generation intervals is affected by non-pharmaceutical interventions; for example, if infected individuals are quarantined, the transmission that is not prevented will more likely occur at shorter generation intervals. In the period before the Jan. 23 lockdown, the mean serial interval (which equals the mean generation interval) was estimated to be 7.8 days, significantly longer than estimates of 5.1 days and 2.6 days for the time periods Jan. 23-29 and Jan. 30-Feb. 13, respectively44. As we are estimating R0 in China before Jan. 23, we focus on the distribution of generation intervals from that period (with the mean of 7.8 days). If all transmission occurred at the estimated mean generation interval of 7.8 days, R0 = e7.8r = 5.9. However, due to the spread of generation intervals, R0 = 5.9 will be a substantial overestimate. R0 can be underestimated by approximating the distribution of generation intervals g(t) by the distribution of serial intervals (estimated as a normal distribution with mean 7.8 days and standard deviation 5.2 days44), which yields R0 = 2.9. (R0 = 2.9 is an underestimate because the distribution of serial intervals generally has a larger variance than the distribution of generation intervals, and serial intervals, unlike generation intervals, can be negative43.) Thus, for China before Jan. 23, 2.9 < R0 < 5.9, but without a distribution of generation intervals it is hard to be significantly more accurate. We estimate R0 = 3.7, which can be obtained by taking the distribution of generation intervals g(t) to be uniformly distributed between 0 and 15.6 days (15.6 being chosen so that the mean generation interval is 7.8 days).

The values of τc that can be achieved depend on the effectiveness of the social distancing measures. The data from China (see Fig. 3) indicate a halving time of as few as 4.78 days is achievable, which corresponds to τc = 6.9 days. However, as a more conservative estimate, we use τc = 15 days from Italy’s data (Fig. 3), which exhibited a particularly slow decline in cases compared with most other European countries41. (The halving time of the daily number of new cases will equal the having time of the number of active infections ic(t), which is why τc can be estimated from this data.)

\({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}]\) is the expected “effective” number of people an infected traveler will infect while visiting region c, taking into account containment efforts. For instance, if the outbreak is contained such that exponential growth never occurs, the effective number of people infected by the traveler is zero, even if the traveler did infect some individuals in region c. We estimate that in the absence of any mitigating policies (mask-wearing, testing, etc.), \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}] \sim {R}_{0} \sim 3.7\); the degree to which \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{c}^{0}]\) differs from R0 depends on how likely a typical traveler is to transmit the virus relative to a typical resident, as well as on the effectiveness of contact tracing and other containment efforts. For regions in which preemptive measures (e.g. mask-wearing, avoiding large gatherings, etc.) are taken, we expect that \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}] \sim {R}_{0} \sim 3.7\) is a substantial overestimate since there is a far greater chance that an infected traveler will not spark an uncontained outbreak (and thus \({i}_{0}^{c}\) will be 0). Good testing and contact tracing policies can also substantially increase the chance that \({i}_{0}^{c}=0\) (thereby reducing \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}]\)) by reducing the probability of community transmission. And a rigorous enough quarantine policy at the border of a region may reduce \({\mathbb{E}}[{i}_{0}^{c}]\) to nearly zero by preventing infected travelers from even having a chance to infect individuals in the region.

The value of pc depends on the frequency of travel out of region c. As previously noted, there is some choice in how to partition a population into a collection of regions. In general, the larger the regions, the lower the frequency of per capita travel out of them but the more homogeneous the application of the social distancing measures. Since pc is smaller for larger regions and Nc is not strongly affected by the size of regions, R* will be lower if larger regions are chosen, but at the cost of the social distancing measures being applied over larger areas for each new outbreak.

Regions do have to be large enough so that transmission between regions can be treated as a first-order (linear) perturbation to a system in which most spread occurs within regions. Thus, how small the regions can be depends on the extent to which travel between them can be reduced. A region could be as small as, for example, a neighborhood if the neighborhood was willing to take measures so as to greatly reduce contact with people outside of it. (We note that the regions within any given collection can differ in both geographic size and in population from one another.)

Although pc will depend on the size of region c as well as the travel behavior of individuals within that region, we still wish to get an estimate of a plausible value for pc. Considering a collection of regions within the U.S. that are large enough such that travel between the regions is predominantly by flight yields a per capita travel rate of 0.004 flights out of a region per person per day. This estimate is obtained by dividing the 1.01 billion total passengers traveling by plane to, from, or within the U.S. in 201845 by the 2018 U.S. population and the number of days in 2018, and then also dividing by 2 so that only flights out of and not into a region are counted. Using this estimate for \({p}_{0}^{c}\) assumes that the probability that an infected individual will travel equals that of the general public. Travelers may on average have more social contacts than the general public or may become infected because of their travels, which could mean that infected individuals are more likely to be traveling than the general public. On the other hand, an individual who has COVID-19 symptoms or has tested positive for COVID-19 may be less likely to travel than the general public. It should also be noted that, compared to 2019 numbers, U.S. air travel in April and May of 2020 was down by approximately a factor of 10 (the effects of a 10-fold reduction in travel are shown in Fig. 4) and U.S. air travel in June was down by approximately a factor of 546.

References

World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus – China. www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/ (2020).

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 72. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331685/nCoVsitrep01Apr2020-eng.pdf (2020).

Watts, D. J., Muhamad, R., Medina, D. C. & Dodds, P. S. Multiscale, resurgent epidemics in a hierarchical metapopulation model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11157–11162 (2005).

Rauch, E. M. & Bar-Yam, Y. Long-range interactions and evolutionary stability in a predator-prey system. Phys. Rev. E 73, 020903 (2006).

Colizza, V., Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. Reaction–diffusion processes and metapopulation models in heterogeneous networks. Nat. Phys. 3, 276–282 (2007).

Colizza, V. & Vespignani, A. Epidemic modeling in metapopulation systems with heterogeneous coupling pattern: theory and simulations. J. Theor. Biol. 251, 450–467 (2008).

Ajelli, M. et al. Comparing large-scale computational approaches to epidemic modeling: agent-based versus structured metapopulation models. BMC Infect. Dis. 10, 190 (2010).

Balcan, D. & Vespignani, A. Invasion threshold in structured populations with recurrent mobility patterns. J. Theor. Biol. 293, 87–100 (2012).

Tanaka, G., Urabe, C. & Aihara, K. Random and targeted interventions for epidemic control in metapopulation models. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–8 (2014).

Ball, F. et al. Seven challenges for metapopulation models of epidemics, including households models. Epidemics 10, 63–67 (2015).

Hasell, J. Which countries have protected both health and the economy in the pandemic? https://ourworldindata.org/covid-health-economy (2020).

Goolsbee, A. & Syverson, C. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline. Working Paper 27432, National Bureau of Economic Research (2020).

Aum, S., Lee, S. Y. T. & Shin, Y. COVID-19 doesn’t need lockdowns to destroy jobs: the effect of local outbreaks in Korea. Working Paper 27264, National Bureau of Economic Research (2020).

Brzezinski, A., Kecht, V. & Van Dijcke, D. The cost of staying open: voluntary social distancing and lockdowns in the US. Working Paper 910, University of Oxford, Department of Economics (2020).

Kardar, M. Statistical Physics of Fields (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Bar-Yam, Y. From big data to important information. Complexity 21, 73–98 (2016).

Siegenfeld, A. F. & Bar-Yam, Y. An introduction to complex systems science and its applications. Complexity 2020, e6105872 (2020).

Diekmann, O., Heesterbeek, J. A. P. & Metz, J. A. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 28, 365–382 (1990).

Ball, F., Mollison, D. & Scalia-Tomba, G. Epidemics with two levels of mixing. Ann. Appl. Probab. 7, 46–89 (1997).

Colizza, V. & Vespignani, A. Invasion threshold in heterogeneous metapopulation networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 148701 (2007).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) frequently asked questions, accessed 28 June 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html (2020).

Lloyd-Smith, J. O., Schreiber, S. J., Kopp, P. E. & Getz, W. M. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359 (2005).

Wallinga, J. & Lipsitch, M. How generation intervals shape the relationship between growth rates and reproductive numbers. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 274, 599–604 (2007).

Ferguson, N. M. et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team (2020).

Siegenfeld, A. F., Taleb, N. N. & Bar-Yam, Y. What models can and cannot tell us about COVID-19. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 16092–16095 (2020).

Riou, J. & Althaus, C. L. Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020. Eurosurveillance 25, 2000058 (2020).

Endo, A. et al. Estimating the overdispersion in COVID-19 transmission using outbreak sizes outside China. Wellcome Open Res. 5, 67 (2020).

Ahmed, W. et al. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 728, 138764 (2020).

Kogan, N. E. et al. An early warning approach to monitor COVID-19 activity with multiple digital traces in near real-time. arXiv:2007.00756 (2020).

Bajardi, P. et al. Human mobility networks, travel restrictions, and the global spread of 2009 H1N1 pandemic. PLoS ONE 6, e16591 (2011).

Poletto, C. et al. Assessing the impact of travel restrictions on international spread of the 2014 West African Ebola epidemic. Eur. Surveill. 19, 20936 (2014).

Brownstein, J. S., Wolfe, C. J. & Mandl, K. D. Empirical evidence for the effect of airline travel on inter-regional influenza spread in the United States. PLoS Med. 3, e401 (2006).

Germann, T. C., Kadau, K., Longini, I. M. & Macken, C. A. Mitigation strategies for pandemic influenza in the United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 5935–5940 (2006).

Epstein, J. M. et al. Controlling pandemic flu: the value of international air travel restrictions. PLoS ONE 2, e401 (2007).

Wells, C. R. et al. Impact of international travel and border control measures on the global spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 7504–7509 (2020).

Chinazzi, M. et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. eaba9757 (2020).

Kraemer, M. U. G. et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. eabb4218 (2020).

Wu, Z. & McGoogan, J. M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA (2020).

Wu, J. T., Leung, K. & Leung, G. M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet 395, 689–697 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. (2020).

Worldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak, accessed 28 August 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

Taleb, N. N. How much data do you need? An operational, pre-asymptotic metric for fat-tailedness. Int. J. Forecast. 35, 677 – 686 (2019).

Park, S. W. et al. Cohort-based approach to understanding the roles of generation and serial intervals in shaping epidemiological dynamics. medRxiv: 2020.06.04.20122713 (2020).

Ali, S. T. et al. Serial interval of SARS-CoV-2 was shortened over time by nonpharmaceutical interventions. Science. eabc9004 (2020).

U.S. Department of Transportation. 2018 traffic data for U.S. airlines and foreign airlines U.S. flights, accessed 12 March 2020. https://www.bts.dot.gov/newsroom/2018-traffic-data-us-airlines-and-foreign-airlines-us-flights.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Transportation Security Administration. TSA checkpoint travel numbers for 2020 and 2019, accessed 28 June 2020. https://www.tsa.gov/coronavirus/passenger-throughput (2020).

Istituto Superiore di Sanita. COVID-19 integrated surveillance: key national data, accessed 21 April 2020. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/en/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-integrated-surveillance-data.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. 1122374 and by the Hertz Foundation. We thank Maxim Rabinovich for helpful early discussions and Edward Kaplan, Philip Welkhoff, Chen Shen, and Daniel Klein for helpful comments. We also thank the editor and the reviewers for their valuable feedback and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F.S. and Y.B.-Y. developed the concepts, performed the analyses, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siegenfeld, A.F., Bar-Yam, Y. The impact of travel and timing in eliminating COVID-19. Commun Phys 3, 204 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00470-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00470-7

This article is cited by

-

Does Travel Spread Infection?—Effects of Social Stirring Simulated on SEIRS Circuit Grid

The Review of Socionetwork Strategies (2024)

-

The impact of travelling on the COVID-19 infection cases in Germany

BMC Infectious Diseases (2022)

-

Novel additive manufacturing applications for communicable disease prevention and control: focus on recent COVID-19 pandemic

Emergent Materials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.