Abstract

This interdisciplinary study, coupling philosophy of law with empirical cognitive science, presents preliminary insight into the role of emotion in criminalization decisions, for both laypeople and legal professionals. While the traditional approach in criminalization theory emphasizes the role of deliberative and reasoned argumentation, this study hypothesizes that affective and emotional processes (i.e., disgust, as indexed by a dispositional proneness to experience disgust) are also associated with the decision to criminalize behavior, in particular virtual child pornography. To test this empirically, an online study (N = 1402) was conducted in which laypeople and legal professionals provided criminalization ratings on four vignettes adapted from criminal law, in which harmfulness and disgustingness were varied orthogonally. They also completed the 25-item Disgust Scale-Revised (DS-R-NL). In line with the hypothesis, (a) the virtual child pornography vignette (characterized as low in harm, high in disgust) was criminalized more readily than the financial harm vignette (high in harm, low in disgust), and (b) disgust sensitivity was associated with the decision to criminalize behavior, especially virtual child pornography, among both lay participants and legal professionals. These findings suggest that emotion can be relevant in shaping criminalization decisions. Exploring this theoretically, the results could serve as a stepping stone towards a new perspective on criminalization, including a “criminalization bias”. Study limitations and implications for legal theory and policymaking are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most fundamental questions in legal theory is: what type of behavior should we bring under the scope of the criminal law (Stanton-Ife, 2022)? Traditionally, in law and philosophy, the answer to this question is considered to be found through reflective, “System 2” thinking (to use Kahneman’s [2011] term), guided by rational deliberation and legal reasoning (Alexander and Sherwin, 2021; Dickson, 2016; Duff, 2014; Dworkin, 1977; Edwards, 2018; Feinberg, 1984, 1988; Hart, 1963; Husak, 2008; Levi, 1949/2013; Simester and Von Hirsch, 2011; Tadros, 2016). In their reasoning, legal scholars draw upon various normative concepts such as the harm principle (Mill, 1859/2005), moral wrongfulness (Devlin, 1965), and legal goods (Birnbaum, 1834). The harm principle, which posits that conduct can only be criminalized to prevent harm to others, is widely considered the most important basis for criminalization (Feinberg, 1984; Hart, 1963; Stanton-Ife, 2022).Footnote 1

However, research in the field of moral psychology and cognitive neuroscience has revealed that moral decision-making encompasses not only “reflective and deliberative” processes but also “affective and emotional” processes (Cushman, 2013; Greene, 2013; Haidt, 2012).Footnote 2 The latter often occur without individuals being aware of them and can result in rationalization (Cushman, 2020; Greene, 2013; Haidt, 2001). In moral philosophy, these insights have been examined extensively, both theoretically (Greene, 2014, 2023; Königs, 2022; Railton, 2014) and empirically (Greene et al., 2001; 2004; Greene and Young, 2020; Miller et al., 2014). More recently, the debate over the new insights on affective and emotional processes has also started to emerge within criminalization theory (Alces & Sapolsky, 2023; Coppelmans, 2013; Patrick and Lieberman, 2018; Persak, 2019; Winter, 2024).Footnote 3 However, the discussion remains primarily theoretical in nature. There are currently few or no empirical studies that specifically investigate the relationship between emotion and the decision to criminalize behavior: it is an “under-represented” area (Persak, 2019; Sznycer and Patrick 2020; Winter, 2024).Footnote 4 Therefore, instead of solely relying on a theoretical approach, and following the rise of “experimental jurisprudence” (Knobe and Shapiro, 2021), we aim to investigate empirically whether emotion is related to the criminalization of behavior.Footnote 5

We intend to do this by investigating to what extent the emotion of disgust (as indexed by a dispositional proneness to experience disgust) is associated with criminalization decisions. Additionally, and strictly from a theoretical perspective, we aim to propose the potential development of a new perspective on criminalization, introducing a potential “criminalization bias”. In order to demonstrate both, we use virtual child pornography as a case study (i.e., images depicting virtual children engaging in virtual sexual conduct).Footnote 6

Virtual child pornography

Technological developments have presented legislators with novel types of behavior that are not easy to characterize in ethical terms, with virtual child pornography as an example (Gillespie, 2018). This topic is a highly contentious and sensitive issue, with arguments both in favor and against criminalizing it, ranging from the harm principle to legal moralism (Gillespie, 2018; Levy, 2002; Luck, 2009; Ost, 2010; Strikwerda, 2011, 2014). Over recent decades, several countries have included (realistic) virtual child pornography under the purview of criminal law, including the United States, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and many EU member states (Bird, 2011; Gillespie, 2018; Witting, 2020).Footnote 7 In good legal tradition (Edwards, 2018), arguments for this are based on “deliberative, legal reasoning”. That is, policymakers, legislators, and legal scholars have been using their cognitive reasoning abilities to develop a line of argumentation.

The central argument refers to the harm principle (Mill, 1859/2005), with legislators claiming that virtual child pornography is—directly or indirectly—harmful to children (Bird, 2011; Gillespie, 2018; McLelland and Yoo, 2007; Williams, 2004; Witting, 2020).Footnote 8 This claim has met with criticism (Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 2002; Bell, 2012; Bird, 2011; Burke, 1997; Gillespie, 2018; Gray, 2021; Ost, 2010; Williams, 2004; Witting, 2020). It is uncertain whether virtual child pornography is harmful, i.e., that online child offenses “fuel” offline child abuse; clear evidence for this is, at best, mixed (Babchishin et al., 2015, 2018; Endrass et al., 2009; Gottfried et al., 2020; Gray, 2021; Houtepen et al., 2014; Ost, 2010; Gillespie, 2018; Nair, 2019; Seto, 2013, 2018; Seto et al., 2011; but see Christensen et al., 2021). Moreover, it is suggested that the availability of virtual child pornography makes people less prone to child sexual abuse by providing an outlet or a means of treatment (Cisneros, 2002; Diamond, 2009; Levy, 2002; Seto, 2013). Here, we sidestep this debate. Obviously, if future evidence demonstrates that virtual child sexual material poses a threat to children, it should be a criminal offense. For present purposes, however, we will follow the most prominent claims in the literature and assume (again: for now) that the harmfulness of virtual child sexual material is—at most—low.

Amongst legal scholars, another line of argumentation is based on legal moralism (Bartel, 2012; Strikwerda, 2011, 2017; Patridge, 2013). However, arguments of this kind are deemed abstract and “rickety” (Ost, 2010) and are generally not considered a legitimate reason in themselves to criminalize conduct (Feinberg, 1988; Luck, 2009; Nair, 2019; Ost, 2010; Simester and Von Hirsch, 2011; Patridge, 2013). As Luck (2009) expresses it in his gamer’s dilemma: “while virtual murder scarcely raises an eyebrow, (…) most people think that virtual pedophilia is not morally permissible”.

This raises the question: what exactly motivates legislators and legal scholars to criminalize virtual child pornography? Arguments are often rooted in unfounded claims about its harmfulness or in abstract legal moralism (Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 2002; Ost, 2010, see also Sood and Darley, 2012), which makes the foundation of this criminalization unclear. What is clear, however, is that both legal scholars and legislators try to find arguments based on “deliberative, legal reasoning”. Given the extremely sensitive nature of virtual child pornography, we hypothesize that the decision to criminalize this conduct is not mainly based on deliberative legal reasoning, but rather is influenced by affective and emotional processes, such as disgust. Hence, we think that virtual child pornography lends itself well for an inquiry into the role of emotion in criminalization decisions.

Moral decision-making and emotional processes

There is considerable evidence to support the claim that affective and emotional processes are relevant for moral judgment (Greene, 2011, 2023; Greene and Young, 2020; Haidt, 2001, 2012; Koenigs et al., 2007; May and Kumar, 2018; McCormick et al., 2016; Prinz, 2007; Slovic et al., 2002; Valdesolo, 2018; van Honk et al., 2022). As to whether these affective and emotional processes are best described in terms of “distinct emotions” such as disgust, anger and fear (Adolphs and Anderson, 2018), “constructed emotions” based on active inference (Feldman Barrett, 2017; Seth and Friston, 2016; Parr, Pezzulo and Friston, 2022) or other computational mechanisms such as “heuristics” (Hjeij and Vilks, 2023; Kahneman, 2011; Slovic et al., 2002) or “model-free reinforcement algorithms” (Cushman, 2013; Crockett, 2013), the debate continues (Fox, 2018; Cushman and Gershman, 2019). For now, in operationalizing affective and emotional processes (Haidt, 2012; Landy and Piazza, 2019), we focus on a line of research that has received much attention, namely disgust (Giner-Sorolla, 2021; Haidt, 2001; Inbar and Pizarro, 2022; Kelly, 2011; Patrick and Lieberman, 2018; Piazza et al., 2018; Tybur et al., 2013).

Moral decision-making and disgust

Disgust is characterized as a powerful, negative emotion and is considered one of the primary outputs of the so-called behavioral immune system, a set of behavioral adaptations to mitigate pathogen threats (Ackerman et al., 2018; Schaller and Park, 2011). Disgust is also argued to underlie moral condemnation (Lieberman and Patrick, 2018; Nussbaum, 2004; Rozin et al., 2008; Tybur et al., 2013), particularly when pathogen threats are involved (Inbar and Pizarro, 2022) and for acts involving physical or spiritual “purity” (Atari et al., 2023; Graham et al., 2013).Footnote 9 First, people commonly experience disgust along with anger and other negative emotions following moral transgressions (Cannon et al., 2011; Chapman et al., 2009; Danovitch and Bloom, 2009; Haidt et al., 1997) and against political outgroups (Landy et al., 2023). Second, some experiments indicate that disgust manipulations lead to harsher moral judgment (e.g., Eskine et al., 2011; Horberg et al., 2009; Schnall et al., 2008; Seidel and Prinz, 2013; Tracy et al., 2019; Van Dillen et al., 2012; Wheatley and Haidt, 2005). Though some experimental effects could not be reproduced or verified by recent attempts (Ghelfi et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2016; Jylkkä et al., 2021; Sanyal et al., 2023). In addition, a meta-analysis reported an average effect size near zero after correcting for publication bias, although specifically gustatory/olfactory disgust inductions did produce a robust and relatively large effect, d = 0.37 (Landy and Goodwin, 2015). Third, one of the more replicable effects within the domain of disgust is the association between disgust sensitivity and attitudes to morally deviant behavior (Inbar and Pizarro, 2022).

Disgust sensitivity

Disgust sensitivity is an individual’s propensity to experience disgust (Haidt et al., 1994).Footnote 10 While state disgust refers to someone’s current emotional experience, trait disgust sensitivity refers to people’s stable tendency to experience disgust over time. Many studies report an association between disgust sensitivity and moral decision-making (Donner et al., 2023). People who are in general more easily disgusted will more readily convict a suspect in a murder, burglary, or sexual assault case (Jones and Fitness, 2008), punish purity violations more harshly and reward purity virtues more strongly (Horberg et al., 2009), and show a stronger preference for order, hierarchy, and deontological judgment (Robinson et al., 2019). They also demonstrate more negative attitudes to organ donation (Mazur and Gormsen, 2020), vaccination (Clifford and Wendell, 2016; Kempthorne and Terrizzi, 2021; Reuben et al., 2020), immigrants and foreign ethnic groups (Aarøe et al. 2017; Brenner and Inbar, 2015; Hodson and Costello, 2007; with cross-national insights from Clifford et al., 2023 and Zakrzewska et al., 2019, 2023), gays and lesbians (Inbar et al., 2009; Kiss et al., 2020; Olatunji, 2008; Terrizzi et al., 2010; Van Leeuwen et al., 2022, Wang et al., 2019), and groups that threaten traditional sexual morality more generally (Crawford et al., 2014; Van Leeuwen et al., 2022). Furthermore, people who are more easily disgusted tend to judge violations of moral and social conventions more harshly, with these effects being most pronounced within the domain of purity (Wagemans et al., 2018; Liuzza et al., 2019), but also observable outside of this domain (Chapman and Anderson, 2014; Karinen and Chapman, 2019); for a meta-analytic review, see Donner et al., (2023).

However, and importantly, it should be noted that sensitivity to several affective states (not only disgust, but also anxiety and anger) predicts extremity in normative and evaluative judgments (Cheng et al., 2013; Landy and Piazza, 2019). This suggests that the relationship between disgust and moral condemnation could be a specification of a broader relationship between affective processes and (moral) evaluation (Inbar and Pizarro, 2022; Piazza et al., 2018). In sum, the measurement of individual differences in disgust sensitivity might provide a good means for examining the role of “emotion” in criminalization decisions.

Current research: criminalization and emotional processes

Given the evidence that emotional processes are associated with the decision to morally condemn behavior, it is reasonable to hypothesize that emotional processes are also associated with the decision to criminalize behavior. At the theoretical level, this has been proposed earlier (Devlin, 1965; Coppelmans, 2013; Kahan, 1999; Moore, 1997; Nussbaum, 2004; Patrick, 2021; Patrick and Lieberman, 2018; Persak, 2019; Sunstein, 2008). Our goal is to provide an early empirical investigation of this claim, by correlating disgust sensitivity with criminalization decisions. This will be depicted through a series of vignettes drawn from criminal law scenarios and traditional criminalization theory. We will use four different vignettes in which we orthogonally varied the levels of harmfulnessFootnote 11 (low, high) and disgustingness (low, high). The scenarios are virtual child pornography (characterized as low in harm, high in disgust), actual child pornography (high harm, high disgust), wearing a sweater with clashing bright colors (low harm, low disgust; Feinberg, 1985), and the use of contingent convertible bonds, which is a high-risk financial instrument (high harm, low disgust; see Berg and Kaserer, 2015; Chan and van Wijnbergen, 2015; Goncharenko et al., 2021; Fatou et al., 2022).

A criminalization bias?

We expect disgust sensitivity to correlate with criminalization decisions in particular for violations that are concrete and personal (Greene, 2009b, 2013) and violations that pertain to the domain of “purity” (Atari et al., 2023; Haidt, 2012); with virtual child pornography being a prime example of both. We expect the correlation with disgust sensitivity to a lesser extent for violations that are abstract and impersonal (Greene, 2009a, 2013), with high-risk financial behavior as an example (i.e., contingent convertible bonds). The “concrete and personal”-distinction is based on Greene (Greene, 2009b, 2013), and points to behavior that is especially expected to trigger an emotional response because it resembles threatening behavior that existed in our ancestors’ personal environment during evolutionary history, such as hitting, killing, rape and other forms of prototypically violent behavior.Footnote 12 The category of “purity,” as part of Moral Foundations Theory and outlined by Haidt (Atari et al. 2023; Graham et al., 2013, 2018; Haidt, 2012), encompasses behaviors that are expected to provoke disgust because they are associated with “bodily and spiritual contamination and degradation” and conflict with “intuitions about sexually deviant practices, chastity and wholesomeness”. Understandably, virtual child pornography falls within both categories. This sexually deviant practice is characterized as “concrete and personal”, as it closely resembles real child sex abuse, behavior that was certainly threatening in Homo sapiens’ personal environment during evolutionary history. It is thus assumed to provoke a strong emotional response. The technically and abstract high-risk financial behavior does not easily align with threats from our ancestors’ evolutionary history, nor does it readily associate with “purity-based” offenses. Consequently, virtual child pornography is believed to elicit a significantly stronger emotional response than high-risk financial behavior.

The noteworthy aspect of these two scenarios is an expected “criminalization bias” (Coppelmans, 2024),Footnote 13 predicted on the assumption that the primary reason here for criminalization is based on the harm principle (as is formally the case in most countries; see Footnote 7). That is, virtual child pornography may not cause significant harm (see above),Footnote 14 but it is expected to elicit a strong aversive emotional reaction leading to a decision to criminalize this conduct.Footnote 15 On the other hand, high-risk financial behavior has the potential to harm individuals and society at large (Berg and Kaserer, 2015; Chan and van Wijnbergen, 2015; Goncharenko et al., 2021; Fatou et al., 2022), yet it generally does not elicit a strong emotional reaction, resulting in a decision not to criminalize this conduct.Footnote 16

Legal expertise and hypotheses

We will test our hypotheses with both lay participants and legal professionals, as we are interested in determining whether legal education and expertise (i.e., professional judgment) can mitigate the impact of affective and emotional processes on moral decision-making. Some research indicates that it does (Baez et al., 2020) or finds it to be context-dependent (Teichman et al. 2024), while other research suggests that education and expertise do not necessarily mitigate the influence of affective and emotional processing across different domains, including legal and philosophical (Horvath and Wiegmann, 2022; Kahan et al., 2016, 2017; Rachlinkski and Wistrich, 2017; Schwitzgebel and Cushman, 2012; Wistrich et al., 2015). Given the scarcity of research specifically in the legal domain, it is valuable to explore this area.

In conclusion, we hypothesize that criminalization ratings are influenced by both the characteristics of the vignettes (harmfulness and disgustingness) and the characteristics of the participants (disgust sensitivity). Specifically, we anticipate that vignettes that are highly disgusting (the virtual and actual child pornography) are more likely to be criminalized than the vignette high in harm, low in disgust (the high-risk financial instrument). Further, we anticipate that these effects will be enhanced for participants that score high on trait disgust sensitivity, and that, according to our theoretical framework, this relationship may be especially strong in the case of virtual child pornography. Finally, we explore to what extend legal expertise, as reported by our sample’s participants, moderates the hypothesized effects of disgust on criminalization decisions.

Methods

Participants and design

The survey was completed by 1725 individuals. Participants who were younger than 16 years old (N = 38) and those who did not rate any of the vignettes (N = 285) were excluded. This resulted in a final sample of 1402 participants (517 males, 876 females, 9 not reported, Mage = 33.57 years, SD = 13.02 years, with 4 missings). Of this sample, a subset of 103 participants who have expertise in the legal domain, such as legislative lawyers, legal policymakers, lawyers, and judges were considered as “experts” in formal, law-based (criminalization) decisions. The remaining sample (N = 1297) was considered to have a lay perspective. The two subsets were matched in terms of age and gender distribution.

We indicated a minimum sample of 600 participants but given our interest in the between person moderators of disgust sensitivity and legal expertise, and to account for possible attrition, we aimed to recruit as large a sample as possible. To determine the sensitivity power analysis (Lakens, 2022) to detect our focal effects, we conducted simulation-based sensitivity analyses following data collection, that allow for simulation of mixed-effects (logistic) regression models that capture multiple sources of random variations (Kumle et al., 2021; see Analytic Strategy and Results for further details).

The study was designed to investigate whether participants’ criminalization decisions depend on vignette characteristics (harm and disgustingness) and/or respondent characteristics (disgust sensitivity). It involved a 2(harm; high versus low) × 2(disgustingness; high versus low) within-participant design with disgust sensitivity as a between-participant continuous variable. The focal dependent variables involved participants’ continuous estimations and binary decisions of criminalization.

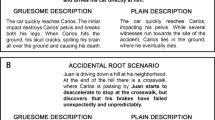

Measures

Four vignettes were created, each depicting a distinct type of behavior. The researchers evaluated the vignettes on two dimensions (high/low) of harmfulness and disgustingness. It is important to note that the level of harm represents the objective harmfulness of the behavior (as established in previous literature; see earlier Introduction) and not the perceived harmfulness by the participants. The four vignettes include: (1) wearing a sweater with clashing bright colors (low harm, low disgust); (2) contingent convertible bonds, explained as a high-risk financial instrument (high harm, low disgust); (3) virtual child pornography (low harm, high disgust); and (4) actual child pornography (high harm, high disgust) (refer to Appendix A for further details). Each vignette presented a brief description of a specific behavior followed by the statement “This type of behavior should be considered a criminal offense.” Participants were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement with this statement through a binary response (agree/disagree) and a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “Strongly Disagree” and 7 represents “Strongly Agree”.

Also, the participants were administered the Dutch version of the revised 25-item Disgust Scale (DS-R-NL; Haidt et al., 1994; modified by Olatunji et al., 2007, Dutch version: M. van Overveld) to measure individual differences in disgust sensitivity. Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in the current study sample was α = 0.78 (N = 1175). The psychometric properties of the DS-R-NL are comparable to those of the English version (Olatunji et al., 2009). Participants were asked to rate their agreement or disagreement with 13 statements and their level of disgust in 12 scenarios. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale, with 0 representing “strongly disagree” or “not at all disgusting” and 4 indicating “strongly agree” or “very disgusting”. An example of a statement: “I might be willing to try eating monkey meat, under some circumstances”. An example af a scenario: “You see maggots on a piece of meat in an outdoor garbage pail”. Higher scores reflect higher levels of disgust sensitivity. Two “catch questions” were excluded from the analysis.

Procedure

Data collection was conducted over the period of February 2017 to February 2018. The questionnaire was administered electronically using the Qualtrics platform. Participants were recruited through various channels to achieve a broad and diverse sample. These channels included university communication networks, Quest Braintainment (a popular science magazine), and multiple social media channels. Specifically, we placed the questionnaire in Facebook community groups from different cities throughout the Netherlands, ranging in size from small villages to medium-sized and large cities, to reach as diverse a population as possible. Expert participants were solicited through multiple law firms and the Dutch Academy for Legislation, an educational institution for legislative lawyers.

After informed consent was obtained, participants completed the survey in three phases. First, demographic information (age, gender, education), legal expertise, occupation, and any connection to the domain of criminal law were obtained. Participants then proceeded to rating each of the four vignettes and subsequently to the 25-item Disgust Sensitivity Scale (DS-R-NL), or vice versa. The four vignettes were each followed by two questions pertaining to criminalization, which was defined as whether the behavior should be subject to criminal law. To counteract any carryover effects, the vignettes were presented in a randomized order. After both questionnaires, participants were debriefed.

All procedures were approved by the Psychology Research Ethics Committee (CEP), protocol number CEP17-0803_260, at Leiden University. Whereas we did not formally pre-register our hypotheses and study set up at the time, the time-stamped approved ethics protocol contains all relevant information, as well as our hypotheses regarding the effects of disgust sensitivity and can be found in the OSF project folder. This folder also contains the raw data, analysis code, and a PDF document of the Qualtrics survey. See: https://osf.io/a49qe.

Results

Data analytic strategy

Linear mixed-effects models and mixed-effects logistic regression models were applied to estimate the effects of vignette type and disgust sensitivity on the continuous and dichotomous criminalization variables, respectively. For this, the “lmer” function in the “lme4” and “lmerTest” packages of R was used (Bates et al., 2015; Kuznetsova et al., 2013). Confidence intervals were obtained using the “confint” function in the “stats” package using Monte Carlo simulations with 1000 bootstrap samples (R Core Team, 2019). Simple effects were obtained using the “lstrends” function in the “lsmeans” package (Lenth, 2016). All models include random intercepts so that individuals are given their own starting points on the dependent variable and, when this increased the fit further and the model did not fail to converge, random slopes for participants, to account for individual differences in the effect of disgust sensitivity on the dependent variable. For the analyses, disgust sensitivity scores were standardized (generating z-scores). The exact coefficients of all outcomes of the regression models can be found in Tables 1–3.

Simulation-based power analyses were conducted for the highest order focal interaction effects (of vignette disgust and harm, and disgust sensitivity), applying the respective mixed-effects models and the compatible simR package (Baayen et al., 2008; Green and MacLeod, 2016). The logic of simulation-based power analyses is as follows: (1) simulate new data sets, (2) analyze each data set and test for statistical significance, and (3) calculate the proportion of significant to all simulations. Monte Carlo simulations were used with 1000 bootstrap samples for the continuous outcome variable and 500 simulations for the dichotomous outcome variable to optimize fitting. Adopting effect sizes from existing data involves the risk of performing the analyses on inflated effect sizes, which in turn would result in an underpowered design. To protect against such bias or uncertainty in the data used for simulation one approach is choosing a conservative smallest effect size of interest. For instance, one could determine the value of the estimated effect size by reducing the observed beta coefficients of interest by 15% (Kumle et al., 2021). Here, instead, we applied the small parameter estimate of b = 0.15 in our simulations (which falls well below the 15% range of the observed coefficients of interest).

The analysis code and the raw data can be retrieved at the study’s open science framework page: https://osf.io/a49qe.

Criminalization ratings (continuous)

To test whether vignette type influences criminalization of behavior, a model including harm (low and high), disgustingness (low and high), and their interaction was fitted to the criminalization ratings. This yielded main effects for both harm (b = 2.51, SE = 0.05, t[3880.83] = 46.25, p < 0.001; 95% CI [2.42, 2.63]) and disgust (b = 3.63, SE = 0.05, t[3882.47] = 67.17, p < 0.001; 95% CI [3.52, 3.72]), such that vignettes that are high in harm resulted in higher criminalization ratings than vignettes low in harm, and vignettes that are high in disgust resulted in higher criminalization ratings than vignettes low in disgust. These main effects were further qualified by a significant interaction effect (b = −0.56, SE = 0.08, t[3884.15] = −7.26, p < 0.001; 95% CI [−0.71, −0.40]). Whether or not the behavior was harmful determined criminalization ratings to a greater extent depending on whether the vignette also induced disgust. That is, harm increased criminalization ratings of low disgust vignettes more (resp. M = 1.22, SE = 0.04 and M = 3.73, SE = 0.04; b = 2.51, SE = 0.05, t[3887] = 46.25, p < 0.001) than of high disgust vignettes (resp. M = 4.84, SE = 0.04 and M = 6.80, SE = 0.04; b = −1.96, SE = 0.05, t[3893] = 36.27, p < 0.001). Likewise, disgust affected the criminalization ratings of low harm vignettes more (b = 3.63, SE = 0.05, t[3889] = 67.17, p < 0.001) than of high harm vignettes (b = 3.1, SE = 0.05, t[3895] = 56.445, p < 0.001). Means and standard deviations are depicted in Fig. 1.

Criminalization decisions (dichotomous)

To determine to what extent the level of disgust and harm affected participants’ decisions to criminalize (yes/no) the behavior described in the vignette we fitted a similar model to the dichotomous criminalization variable. Comparable main effects were observed for the vignettes’ level of disgust (b = 4.92, SE = 0.26, z = 17.71, p < 0.001; 95% CI [4.45, 5.49]) and harm (b = 3.80, SE = 0.25, z = 15.09, p < 0.001; 95% CI [3.34, 4.39]). Participants were more inclined to criminalize behavior high compared to low in disgust or harm. Contrary to the analysis of continuous criminalization ratings, there was no significant interaction effect between disgust and harm level on criminalization, b = 0.17, SE = 0.37, z = 0.46, p = 0.65; 95% CI [−0.61, 1.00]. Table 2 depicts the decision frequencies for the various vignette.

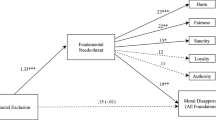

Disgust sensitivity as a moderator of the effects of vignette characteristics on criminalization

Next, we examined whether individual differences in disgust sensitivity further moderated the effects of disgust and harm levels of the vignette on criminalization. To do so, a full-factorial model including disgust level (low and high), harm level (low and high), and disgust sensitivity (standardized scores), was fitted to the data. For the continuous outcome of criminalization, this analysis revealed in addition to the above-reported effects, an interaction effect of the vignette’s disgust level and disgust sensitivity (b = 0.47, SE = 0.06, t[3602.40] = 8.53, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.36, 0.58]), and the vignette’s harm level and disgust sensitivity (b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, t[3602.80] = 3.28, p = 0.002; 95% CI [0.07, 0.29]). These two-way interactions were moreover qualified by a three-way interaction between disgust level, harm level, and disgust sensitivity (b = −0.66, SE = 0.08, t[3602.82] = −8.742, p < 0.001; 95% CI [−0.83, −0.51]). Disgust sensitivity did not affect criminalization ratings of vignettes low in both harm and disgust (b = 0.01, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.09]) or high in both harm and disgust (b = 0.0005, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.08]). However, individual differences in disgust sensitivity did affect criminalization ratings for the low disgust, high harm vignette (b = 0.19, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.11, 0.27]), and, even more so, for the low harm, high disgust vignette (b = 0.48, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.41, 0.56]). In both cases, more disgust-sensitive individuals gave higher criminalization ratings than less disgust-sensitive individuals (see Fig. 2).

A simulation-based power sensitivity analysis of the three-way interaction effect, estimating a small effect size of b = 0.15 and an alpha level of 0.05, yielded a power of 100%, 95% CI [99.63, 100]. Hence, our sample seemed sufficiently large to detect the effect size of interest.

The pattern was not fully replicated when we fitted a similar model to the dichotomous criminalization decisions. Here, we observed a significant main effect of disgust sensitivity (b = 0.59, SE = 0.26, z = 2.29, p = 0.02; 95% CI [0.04, 1.17]), in addition to the previously reported main effects of the vignette’s levels of disgust and harm. Thus, participants were overall more inclined to decide that behavior should be criminalized, the greater their disgust sensitivity. However, only an interaction effect of the vignette’s harm level and disgust sensitivity reached significance (b = 0.54, SE = 0.27, z = 2.04, p = 0.04; 95% CI [−1.10, 0 L.04]; see Table 1).

Note though, that those criminalization decisions for the vignettes that were either both low or both high in harm and disgust showed very little variation (i.e., 99% decided against, or for, respectively), which problematizes the fitting of more complex models including interaction terms with a continuous between-participant variable. Hence, we followed up this analysis with a more focal model that only included the high harm, low disgust and low harm, high disgust vignettes, which, according to our analysis of the continuous criminalization measure, should be most affected by individual differences in disgust sensitivity (given that these vignettes yielded more variation to begin with). In addition to a main effect of vignette similar to the previously observed pattern of results (b = 1.18, SE = 0.09, z = 12.71, p < 0.001; 95% CI [1.00, 1.36]), this analysis yielded an interaction effect of disgust sensitivity and vignette (b = 0.49, SE = 0.09, z = 5.30, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.30, 0.68]). This indicates that, in line with the pattern of results for the continuous criminalization measure, disgust sensitivity was more strongly associated with criminalization tendencies of the low harm, high disgust vignette, than the low disgust, high harm vignette.

A simulation-based power sensitivity analysis of this interaction effect, estimating a small effect size of b = 0.15 (well below the observed effect size of 0.49), and an alpha level of 0.05, yielded a power of 91%, 95% CI [88.82, 93.88]. Thus, our sample seemed sufficiently powered to detect the effect size of interest.

Moderation by expertise

As a final step, we explored whether the above-reported effects of the vignette’s levels of harm and disgust and individual differences in disgust sensitivity were mitigated by professional expertise. To this end, we fitted a full-factorial model including disgust level (low and high), harm level (low and high), disgust sensitivity (standardized), and expertise level (1 = layman, 2 = expert). For the continuous criminalization ratings, in addition to the previously reported effects, we observed a significant two-way interaction of the vignette’s harm level and expertise level that was further qualified by a three-way interaction between the vignettes’ disgust and harm levels, and expertise (b = 0.94, SE = 0.29, t[3592.41] = 3.19, p = 0.001; 95% CI [0.35, 1.53]), (see Fig. 3).

As depicted in Fig. 3, focused comparisons of the estimated means showed that whereas experts and laypeople displayed overall similar rating patterns, laypeople criminalized the high harm low disgust vignette (M = 4.87, SE = 0.04) more than experts (M = 3.23, SE = 0.15, b = 0.55, SE = 0.15, t[4745] = 3.64, p = 0.002). The four-way interaction between disgust level, harm level, disgust sensitivity, and expertise level was not significant, t[3592.31] = 0.83, p = 0.41, suggesting that both groups were equally affected by this individual difference variable. See for an overview of the effects, Table 3. A similar model fitted to the dichotomous criminalization decisions did not yield any additional significant effects.

Discussion

The results of this study offer an early empirical insight into the association between emotion (i.e., disgust) and the decision to criminalize behavior, for both laypeople and legal professionals. An analysis was conducted to determine what type of behavior (scored in terms of harmfulness and disgustingness) was more likely to be criminalized, and to what extent disgust sensitivity was associated with this decision. Our results partly confirmed what we expected. Participants—both laypeople and legal experts—were more likely to criminalize behavior that was highly disgusting (child pornography), even when it was low in harm (virtual child pornography),Footnote 17 compared to behavior that is high in harm but less disgusting (high-risk financial behavior), see Fig. 1. This is interesting from a theoretical perspective, as one would expect that behaviors that are potentially very harmful would be criminalized more readily than those that are relatively harmless, particularly given the preeminent position of the harm principle in normative theory (Feinberg, 1984; Mill, 1859/2005; Stanton-Ife, 2022).

Additionally, our results indicate that individual variations in disgust sensitivity further moderated this pattern, such that disgust sensitivity was positively correlated with criminalization ratings for the high-risk financial behavior scenario (low disgust/high harm) and even more so for the virtual child pornography scenario (low harm/high disgust). In both scenarios, individuals who demonstrated a higher level of disgust sensitivity provided higher criminalization ratings compared to individuals with lower levels of disgust sensitivity (as depicted in Fig. 2). For the virtual child pornography vignette, this aligns well with previous literature, which has established a relationship between disgust and moral evaluations (Giner-Sorolla et al., 2018; Karinen and Chapman, 2019) and has shown that an individual’s level of disgust sensitivity is positively correlated with their level of moral condemnation, especially within the “purity-domain” (Chapman and Anderson, 2014; Jones and Fitness, 2008; Inbar and Pizarro, 2022; Karinen and Chapman, 2019; Van Leeuwen et al., 2022; Wagemans et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). For the high-risk financial scenario however, it is intriguing that disgust sensitivity is at all linked to this scenario, considering its abstract and non-visceral nature. However, there is also evidence suggesting that disgust sensitivity has a modest association with less visceral moral transgressions outside of the purity domain, like issues of fairness and honesty (Van Dillen et al., 2012), theft, fraud, and breaches of social conventions (Jones and Fitness, 2008; Chapman and Anderson, 2014), as well as instances of mild physical and psychological harm (Karinen and Chapman, 2019). It is worth noting, though, that this relationship is markedly less strong than the relationship with transgressions in the purity domain (Wagemans et al., 2018; for a meta-analytic review, see Donner et al., 2023). As noted, the positive association of trait disgust sensitivity with criminalization ratings appeared most pronounced for the virtual child pornography vignette (low harm/high disgust) and this pattern of results was mimicked for the dichotomous criminalization measure.

Existing literature also offers insight into why individuals with high levels of disgust sensitivity rated virtual child pornography as more deserving of criminalization compared to high-risk financial behavior. Consistent with the frameworks presented by Haidt and Greene (Haidt 2012; Graham et al., 2013; Greene, 2013, 2014), virtual child pornography can be categorized as a personal violation within the purity domain, likely eliciting a strong emotional reaction. In contrast, the high-risk financial instrument, being abstract and impersonal, is less prone to provoke such a strong emotional response (Greene, 2009b, 2013). It is thus not surprising, and as hypothesized, that the association found in the virtual child pornography vignette is more pronounced than the association observed in the financial instrument vignette.

Disgust sensitivity did not affect criminalization ratings for the sweater (low harm, low disgust) and the actual child pornography vignettes (high harm, high disgust). This is probably due to little variation in the criminalization judgments for those scenarios (i.e., strong floor and ceiling effects, see Fig. 2). Wearing a sweater with clashing bright colors is not behavior that any individual (whether low or high in disgust sensitivity) would want to bring under the scope of the criminal law. And even a low disgust-sensitive individual would see the sense in criminalizing actual child pornography, because it is both extremely harmful and disgusting. Comparing the cases of the sweater and actual child pornography to virtual child pornography and financial crime suggests that individual variations in disgust sensitivity play a particularly prominent role in situations where the relationship between harm and disgust is ambiguous. Future research could address this idea further to assess the robustness of this effect.

Laypeople vs. legal professionals

A remarkable aspect in these results is the impact of legal education and expertise (i.e., professional judgment). Legal professionals displayed - to the same extent as laypeople - a similar rating pattern in criminalizing virtual child pornography (low harm, high disgust). Moreover, for experts and laypeople a similar significant relationship was found between disgust sensitivity and the criminalization of virtual child pornography. These findings seem to indicate that legal education and expertise do not mitigate the effects of emotional processing, which contrasts with earlier research findings reported by Baez et al. (2020). Also surprising is that experts criminalized the high-risk financial scenario (characterized as high in harm, low in disgust) less frequently than laypeople, as one would expect them to do so more often, again, given the dominant position of the harm principle in (continental) legal theory (Mill, 1859/2005; Stanton-Ife, 2022). Although one might argue in light of these findings that the design of the vignettes may not be entirely accurate, several other potential reasons might explain these observations. First, literature on motivated reasoning indicates that (legal) education and expertise do not necessarily act as a buffer against affective and emotional processing (Kahan et al., 2016, 2017; Rachlinkski and Wistrich, 2017; Wistrich et al., 2015). On the contrary: gaining knowledge, education and expertise (all of which can reasonably be understood to cultivate proficiency in conscious, analytical forms of reasoning; Kahan et al., 2016) can cause people to adhere even more strongly to their affective and cultural (group-identity) beliefs because they are better at finding evidence and arguments to support their position and to rationalize away the rest (Kahan, 2015, 2017; Baekgaard et al., 2019; Savadori et al., 2022). Second, regarding the high-risk financial scenario, it is also possible that legal experts emphasize the complexity of the potential harmfulness in the vignette more than laypeople, thereby opting for the default option: not criminalizing the behavior.

To fully elucidate the impact of legal expertise on moral decision-making and criminalization, further research is needed, particularly with stricter controlled vignettes, in different legal contexts and across varied forms of expertise. Also, the effects observed should be considered exploratory, as they were tested in a sample that may not have been adequately powered to detect the moderating effect of expertise. Hence, future studies should further examine the robustness of these findings. In addition, qualitative research in particular could offer deeper insights into the decision-making process of (legal) professionals.

Theoretical implications

Our observations could have important implications for criminalization theory. As indicated, scholars in this domain are generally assumed to rely heavily on deliberative, reasoned processes when theorizing about criminalization (Alexander and Sherwin, 2021; Dickson, 2016; Dworkin, 1977; Duff, 2014; Edwards, 2018; Levi, 1949/2013; Posner, 2010; Simester and Von Hirsch, 2011; Sunstein, 2008; Tadros, 2016). The question is whether this assumption is correct. Our findings, albeit preliminary, support the idea that emotional processes are significantly associated with the decision to criminalize behavior. Combining these findings with existing literature in cognitive science (Atari et al., 2023; Greene, 2014; Haidt, 2012; Sznycer and Patrick, 2020) could give rise to the hypothesis that legal scholars besides reasoned processes additionally rely on emotional processes when theorizing about criminalization (Lieberman and Patrick, 2018; Kahan, 1999; Nussbaum, 2004; Persak, 2019; Sunstein, 2008). Based on the same body of literature, a further hypothesis could be that while doing so, they often rationalize their emotional preferences, rather than reason towards a reflective outcome (Cushman, 2020; Greene, 2014; Haidt, 2001; Kahan, 2013; Lieberman and Patrick, 2018; Sood and Darley, 2012). However, this remains purely theoretical. Further research on this topic would be both interesting and beneficial, ideally combining quantitative and qualitative research methods.

As an aside, it is important to note that it has long been acknowledged by criminalization scholars that emotions can play a role in criminalization decisions (Devlin, 1965; Dworkin, 1977; Hart, 1963; Moore, 1997). Some scholars even find justification in them (Devlin, 1965; Moore, 1997). However, the more recent findings from moral psychology and cognitive neuroscience (Cushman, 2013; Greene, 2013; Greene & Young 2020; Haidt, 2012) attribute a much larger role to affective and emotional processes in moral decision-making than generally considered amongst (legal) scholars, including subsequent rationalization mechanisms (refer to endnote 3).

Towards a new perspective on criminalization

Theorizing this further, our findings could provide a stepping stone for the development of a new perspective on criminalization theory (Coppelmans, 2024), including a potential “criminalization bias” (refer to endnote 13). This perspective would be both descriptive and normative, and would place much more emphasis on affective and emotional processes, along with the accompanying rationalization mechanisms, than usual in traditional criminalization theory (e.g., Duff, 2014; Dworkin, 1977; Edwards, 2018; Feinberg, 1984, 1988; Hart; 1963; Husak, 2008; Posner, 2010; Simester and Von Hirsch, 2011). Hence, the perspective could be named a “dual-process theory of criminalization” (Coppelmans, 2024; Winter, 2024),Footnote 18 a corollary of Greene’s dual-process theory of moral decision-making (Greene, 2013, 2014, 2017). The dual-process theory of criminalization would posit, first, that criminalization decisions and theory are grounded in both reflective and affective (intuitive) processes;Footnote 19 where the latter often result to rationalization (see also Sood and Darley, 2012). Second, that affective processes are especially prevalent in evaluating “personal” types of (criminal) behavior.Footnote 20 Third, and importantly, that our thinking about criminalization is not always “reliable”. It can be biased, especially when evaluating so-called “modern (criminal) offenses”: which leads to the introduction of a potential “criminalization bias”.

Traditional and modern criminal offenses

To elucidate, the deep evolutionary origins of our emotions and justice intuitions (Greene, 2013; Haidt, 2012; Jones, 1999; Sznycer and Patrick, 2020; Williams and Patrick, 2023) make it conceivable that our emotions are very well attuned to dealing with what we can call “traditional criminal offenses” (i.e., murder, burglary, aggressive behavior, sexual abuse: the so-called malum in se)—simply because our emotional reactions have millions of years of (cumulative cultural) evolutionary experience with them.Footnote 21 Our emotional system has learned to give a strong aversive signal when confronted with behavior that was threatening in our personal environment during our evolutionary history (Greene, 2013); which is subsequently reinforced in a culturally-specific manner (Atari et al., 2023 Dunstone and Caldwell, 2018; Graham et al., 2018; Henrich and Muthukrishna, 2021).Footnote 22 However, our emotions are much less attuned to deal with what we can call “modern criminal offenses”, offenses that are extremely recent on an evolutionary timescale (see also Coppelmans, 2024; Winter, 2024). These can be diverse, such as environmental harms (e.g., climate change, ecocide), abstract financial behavior (e.g., credit default swaps, dark pools, tax avoidance), offenses that arise from (bio)technological developments (e.g., A.I., robot sex, child sex dolls, deepfakes, genetic engineering, stem cell research, abortion) and offenses that stem from intercultural mixing (e.g., wearing a burqa or forced marriage). During evolutionary history, these offenses were certainly not threatening, as they simply did not exist, at least not in the personal environment of our ancestors (in their present form and intensity).Footnote 23 This new perspective on criminalization proposes that our thinking about specifically these modern criminal offenses can be biased—simply because our affective and emotional processes have very little (evolutionary) experience with them (Coppelmans, 2024; Greene, 2013; See also Brosnan and Jones, 2023).Footnote 24

The criminalization bias

This mismatch can be named the “criminalization bias” (Coppelmans, 2024),Footnote 25 in which the deviation can go two ways.Footnote 26 First, our emotional responses could ‘overreact’, that is, react too quickly and too harshly, to personal, emotion-provoking offenses that, in reality, are quite harmlessFootnote 27 (e.g., incest while using contraceptives [Haidt, 2001], child sex dolls, virtual child pornography). Second, our emotions could “underreact”, that is, react very weakly or do not react at all, to abstract and impersonal, non-emotion-provoking offenses that in reality can be quite harmful (e.g., abstract and invisible hazards like climate change, artificial intelligence, tax avoidance, high-risk financial behavior, etc.) (see also Greene, 2013). Both ways leading to biased evaluations of harmfulness in light of criminalization decisions.Footnote 28 Crucially, it should be noted that while these ideas are grounded in theory, more empirical research is necessary to corroborate them.

Limitations and future directions

Our research has several limitations. First, considering our vignettes, we deliberately selected renowned examples from criminalization theory and practice (e.g., Feinberg 1985; Simester and Von Hirsch 2011). This approach was motivated by a desire to maximize ecological validity. We prioritized scenarios that already existed in criminalization literature, ensuring their relevance and applicability to (a) our legal professional participants and (b) the judicial part of our audience: legal scholars, policymakers and legal practitioners. However, the disparities in the orthogonality, length and complexity of the vignettes, notably in the high harm, low-disgust financial scenario, might have introduced potential confounds. While our primary goal was to ensure each vignette clearly represented its intended scenario, this occasionally resulted in additional detail, which may have influenced participants’ perceptions or responses. Future research should consider standardizing vignette complexity to minimize potential biases.Footnote 29 Also, the use of less complex “abstract/financial crime”-scenarios is advisable (such as tax avoidance by large corporates or large scale privacy infringement). Additionally, and importantly, we recognize the need for more rigorous testing and validation of these scenarios in subsequent studies.

Second, the positive association of trait disgust sensitivity with criminalization ratings appeared most pronounced for the low harm/high disgust vignette (virtual child pornography). However, it is good to note that the observed effect primarily rests on a relative claim: that the effect size of the disgust sensitivity effect is larger for the low harm/high disgust scenario (virtual child pornography) than for the high harm/low disgust scenario (abstract financial crime).Footnote 30 It would therefore be prudent to exercise caution in drawing overly definitive conclusions. Also, it is important to note that we used only one vignette per harm/disgust-manipulation, which limits the generalization of the results to other behaviors. For future research it is advisable to use multiple vignettes and examine various types of behavior.

Third, due to its extensive documentation in the literature, our study focused exclusively on disgust as a proxy for the role of emotion (Giner-Sorolla et al., 2018; Rozin et al., 2008; Russell and Giner-Sorolla, 2013). However, other affective and emotional processes could also play a role in criminalization decisions (Haidt, 2012; Greene 2013). It has been suggested that sensitivity to various affective states (not just disgust, but also anxiety and anger) predicts extremity in evaluative judgments (Cheng et al., 2013; Landy and Piazza, 2019). This would indicate that the connection between disgust and moral condemnation is part of a wider relationship between (negative valenced) affect and moral judgment (Piazza et al., 2018). Therefore, for future research, it is important to explore the role of various emotions in criminalization, by focusing on the diverse ways in which affective and emotional processes contribute to criminalization decisions (Atari et al., 2023; Cushman, 2013; Greene and Young, 2020; Greene, 2023).

Fourth, concerning our legal professional participants, it is important to highlight that making conclusions based solely on the responses from these experts can be intricate due to the smaller effect size (N = 103) when compared to the overall participant sample (N = 1297). Furthermore, our group of legal experts was varied, comprising legislative lawyers, legal policymakers, lawyers and judges. For future research, maintaining greater consistency within the participant group might be advisable. It could also be advisable to provide legal professionals with a monetary incentive, which appears to enhance the accuracy of responses from professionals (Kahan, 2015).

Finally, while this study may not present novel insights from a purely psychological perspective, it aims to contribute to the interdisciplinary field of legal-psychological research, particularly within the realm of criminalization. The limitations we have identified highlight the complex interplay between emotional responses and criminalization decisions. Our findings suggest a potential link between these variables, a link that seems to hold true even among experienced legal professionals. To unravel the precise dynamics of this relationship, future research will need to employ more sophisticated research methodologies and deploy vignettes that have undergone more rigorous validation.

Practical implications

Lastly, our findings have potential practical implications. They suggest that emotion, specifically disgust, is associated with the decision to criminalize behavior, in particular virtual child pornography. This might be informative for legislatures and policymakers. As previously noted, many countries have subjected (realistic) virtual child pornography to criminal law, reasoning that such content is harmful (Bird, 2011; Gillespie, 2018; Williams, 2004; Witting, 2020). Yet, our study provides an alternative, albeit preliminary, perspective: the decision to criminalize virtual child pornography might stem less from reasoned judgment and more from an emotional response, possibly triggered by associations with real child sexual abuse.

This descriptive finding (if it holds up) could have practical, normative implications. That is, virtual child pornography resembles a so-called “modern criminal offense”: it is a consequence of recent technological developments that allow for highly realistic simulations of behavior. The (cumulative cultural) evolutionary origins of our emotions (Brosnan and Jones, 2023; Greene, 2013; Haidt, 2012; Henrich and Muthukrishna, 2021; Sznycer and Patrick, 2020; Williams and Patrick, 2023) implicate that it is quite conceivable that our emotions are not well attuned to evaluate the danger posed by such virtual types of offenses: our emotional moral thinking is “unfamiliar” with them. During thousands of years of (cultural) evolution, sex with children was only very real, and very harmful:Footnote 31 it was never realistically virtual.Footnote 32 Thus, it can be argued that during these thousands of years our emotions have (genetically, culturally, individually) “learned” to react strongly to anything that merely resembles real sex with children.Footnote 33 Unsurprisingly, this leads to bias when evaluating the legitimacy of virtual child pornography: our emotional moral brain simply does not have (cumulative cultural) evolutionary experience with the virtual version and therefore reacts (one could say: ‘overreacts’) with extreme aversion. That is, ‘seeing’ danger where there is none.Footnote 34 This way, virtual child pornography may well be a moral illusion: a type of conduct that is perceived as extremely harmful, while in reality, it is not.Footnote 35 In other words, our cognition could contain a criminalization bias when considering the harmfulness of virtual child pornography in the context of criminalization.Footnote 36

Normative implications?

If we are willing to accept these descriptive hypotheses, the normative question arises: do we consider our emotions—which very likely evolved in order to prevent real child sex abuse—to be a morally relevant factor when evaluating virtual child sex abuse? And if not, are we willing to accept that, in the words of Luck (2009), we should “bite the virtual bullet”? That is, setting our emotions aside and taking a more nuanced, reasoned approach to virtual child sexual material: solely evaluating it on its consequences (philosophically, this constitutes a debunking argument; Greene, 2014; Königs, 2022; Singer, 2005). Should it perhaps be legalized for certain populations, under certain restrictions, as a means for research and/or treatment (Malamuth and Huppin, 2007; McLelland, 2012; McLelland and Yoo 2007; Seto, 2013)?Footnote 37 On the other hand, the answer can also be affirmative: yes, we should consider our emotions a morally relevant factor when criminalizing virtual child pornography. In that case, however, it is important to establish the criminalization on the proper normative foundation: not based on the harm principle (Feinberg, 1984; Mill, 1859/2005), as is still formal practice in many countries, but rather on the offense principle, by deeming it “obscene” (Feinberg, 1985).Footnote 38 Determining which course of action is the most ethical, is a matter for another time. Looking forward to a future of ever-advancing technological innovations and ever-changing criminal offenses, these questions will become more and more pressing. The ultimate answer, however, remains with us.

Conclusion

The results from this study offer an empirical, albeit preliminary, insight into the role of emotion in criminalization decisions. While the most central legal principle in criminalization theory is the harm principle (Mill, 1859/2005), both laypeople and legal professionals were more inclined to criminalize virtual child pornography (characterized as low in harm) compared to high-risk financial behavior (characterized as high in harm). Furthermore, disgust sensitivity was associated with these decisions, particularly concerning the virtual child pornography scenario—again, for both laypeople and legal professionals. This indicates that emotion can be associated with the decision to criminalize behavior. Theoretically, this could have multiple implications for criminalization theory, one of which being the potential presence of a “criminalization bias” in thinking about morality and the law (Coppelmans, 2024). More research is encouraged to corroborate these findings and to draw more substantive conclusions.

From a broader perspective, the findings also touch upon another point: the contribution of empirical cognitive science to philosophy of law, more specifically to criminalization theory. Criminalization is a fundamental topic, with substantial stakes at hand. Therefore, it seems crucial that we “know what we are doing” when considering the criminalization of behavior, in other words, that we understand the actual (cognitive, philosophical) foundations upon which a decision is based or a theory is constructed. Moral psychology and cognitive neuroscience embody the tools to gain this understanding (Brosnan and Jones, 2023; Greene and Young, 2020).Footnote 39 It seems therefore only rational to use these scientific tools to garner deeper insights into the foundations of our moral thinking—ideally leading to better-informed decisions and more refined theories in criminal law. This empirical way appears to be the right direction to pursue (Knobe and Shapiro, 2021), towards criminalization theory as a truly interdisciplinary enterprise.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Open Science Framework repository: https://osf.io/a49qe.

Notes

This is a topic of debate: most notably between defenders of the harm principle and “legal moralists”. Legal moralism is the belief that [prima facie] it can be morally justifiable to prohibit certain conduct based on the belief that it is morally wrongful (i.e., inherently immoral or immoral based on other normative ethical principles), even if it does not cause harm or offense to the individual or to others (Duff, 2014; Moore, 1997; Stanton-Ife, 2022). Another theoretical justification for criminalization is the offense principle, e.g., the “obscenity” of the conduct (Feinberg, 1985). For the purpose of this study, we won’t delve deeper into legal moralism or the offense principle. Relevant is that criminalization is always a balancing act of considerations, and this study focuses on one of these considerations, that is “harmfulness”. Harm itself is defined as a “(potential) setback of a welfare interest, i.e., one’s body or property, that is a wrong” (see also Feinberg, 1984).

This view is grounded in dual-process theory (Kahneman, 2011; Sherman et al., 2014), with affective and reflective processes also referred to as “System 1 and System 2”, “moral intuition and moral reasoning”, “habit and goal-directed behavior” and more recently “model-free and model-based learning algorithms” (Cushman, 2013; Greene, 2013, 2017; Haidt, 2012).

Two considerations are noteworthy. (1) First, there is extensive literature concerning the relationship between emotion and other area’s within criminal legal theory (Bandes et al., 2021; Brosnan and Jones, 2023; Jones, 1999; Kahan and Nussbaum, 1996; see for an overview Abrams and Keren, 2010; Patrick, 2015; Persak, 2019); however, the role of emotional processes in specifically the criminalization of behavior was under-explored (Persak, 2019, p. 48. Some notable exceptions are Kahan, 1999; Moore, 1997; Nussbaum, 1999, 2004; Prince, 2010; Sunstein, 2008). (2) Second, within criminalization theory, it has long been acknowledged that emotions can play a (key) role in criminalization decisions (Devlin, 1965; Dworkin, 1977; Hart, 1963; most thoroughly: Moore, 1997). Some scholars even find justification in them (Devlin, 1965; Moore, 1997). However, the literature on criminalization has yet to extensively incorporate the more recent findings from moral psychology and cognitive (computational) neuroscience, on affective and emotional processing in moral judgment (Haidt, 2012; Greene and Young, 2020), dual-process morality (Greene, 2013, 2023), evolutionary origins of morality (Joyce, 2007; Greene, 2013), model-based and model-free learning mechanisms (Cushman, 2013; Crockett, 2013), biases and heuristics (Kahneman, 2011), rationalization (Cushman, 2020; Haidt, 2001) and debunking arguments (Greene, 2014; Königs, 2022). An important difference is that the vast majority of legal scholars still seem to regard rational deliberation and legal reasoning as doing ‘most of the work’ in moral judgment (with Moore, 1997 as a notable exception), and consider ‘emotion’ as having a minor role, or, at least, fall within our awareness (Alexander and Sherwin, 2021; also according to Sunstein, 2008). This differs from recent models on moral judgment, which consider affective and emotional processes (or: model-free learning algorithms) to be doing ‘most of the work’ and often operating unconsciously; whereas reflective and reasoned processes are considered to play a lesser role than previously thought, and are often a rationalization (Greene, 2008, 2013, 2014; Haidt, 2001; Kahneman, 2011; see also Cushman, 2020; Sood and Darley, 2012).

In this paper, we define “virtual material” as material that is created without involving any real or identifiable minors, such as computer-animated videos and images, cartoons, drawings, sculptures, and paintings. This material is also known as “virtual child sexual exploitation material”, in reference to its potential harmful effects. For more information on this definition, refer to Gillespie (2018).

E.g., Child Pornography Prevention Act 1996 (invalidated by Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 2002); PROTECT Act 2003; Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse 2007 (Lanzarote Convention); Coroners and Justice Act 2009; Combating sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children and child pornography (Directive 2011/93/EU).

Of course, this is a topic of much debate, not just regarding whether the conduct is harmful, but also what constitutes harm. For instance: young children viewing virtual child sexual material through a search engine is harmful as well. Also, some virtual material is indistinguishable from actual material, which could harm the investigation and prosecution of the latter. For present purposes, we want to further narrow the definition of virtual child pornography to only include material provided by healthcare providers and only accessible in secure, online environments. This way, we can concentrate on the risk that virtual child pornography may increase child abuse either by fueling it after consumption or through other means.

Within Moral Foundations Theory, Haidt and colleagues (Atari et al., 2022) propose that our moral intuitions are based on various “psychological foundations”, which they categorize as—amongst others—Care, Equality, Proportionality, Loyalty, Authority, and Purity. The category of Purity pertains to intuitions about avoiding physical contamination and spiritual degeneration of the mind and soul, as well as the degradation of society as a whole, encompassing virtues like chastity, wholesomeness, and control of desires. The emotion of disgust is thought to translate into moral beliefs regarding the purity of the body and soul, and the impurity of groups with a different, perceived ‘unclean’ lifestyle such as immigrants, other religious and cultural groups and groups with a sexual lifestyle that deviates from the norm, e.g., LGBTQIA) (Atari et al., 2022; Graham et al., 2013, 2018. See also: Gray et al., 2023; Piazza and Sousa, 2023).

This is not the perceived harmfulness of the conduct by participants; it is the “objective” harmfulness of the conduct based on existing literature (see Introduction).

It is important to note that, evidently, not only “genetic” mechanisms but also (cumulative) cultural and individual learning mechanisms influence our affective and emotional reactions to moral cases (Graham et al., 2013, 2018; Greene, 2013, 2017). The term “evolutionary” in this paper therefore refers to both genetic and cumulative cultural evolution (Henrich and Muthukrishna, 2021).

We define bias as an (unconscious) systematic and specific deviation in our cognition from a certain norm, in this case the norm being the actual harmfulness of behavior when evaluating criminalization decisions. The proposed “criminalization bias” is thought to be driven by (the absence of) a strong emotional, model-free response, and could therefore also be referred to as an “emotional bias in criminalization decisions”. It is regarderd as a broadly applicable bias within criminalization theory, explaining its name. The bias is based on a general-purpose heuristic: the affect heuristic (Kahneman, 2016; Slovic et al., 2002). The question what factors give rise to our affective responses (and could lead to biased criminalization decisions) is still up for research. Personalness of harm could play a role, so can virtuality, the presence of harm as a side-effect (Greene, 2014) or the perspective one takes when evaluating harm (Miller et al., 2014), etc.

Again, when provided by healthcare providers and only accessible in secure, online environments.

And leading to a perception of the behavior as (very) harmful (see also Sood and Darley, 2012).

And leading to a perception of the behavior as low(er) in harm. When the behavior has already been criminalized, it may result in a decision either not to prosecute or to impose a relatively milder sentence. However, this area warrants further investigation.

Again, harmfulness was determined by the researchers based on existing literature (refer to Introduction). Of course, further research with other types of behavior is warranted to corroborate these findings.

In psychology, the computational perspective is on the rise (Cushman and Gershman, 2019). Hence, the “dual” processes are increasingly characterized in computational terms, such as model-based and model-free reinforcement learning algorithms (Cushman, 2013; Crockett, 2013; Greene, 2017). Model-based algorithms correspond with more “reasoned” thinking: it attaches values to outcomes, and indirect to actions, based on an explicit model of cause and effect relationships between actions and their outcomes, and the values attached to those outcomes. In contrast, model-free algorithms correspond with intuitive thinking: it relies on accessing values directly attached to actions, based on previous reinforcement. It is important to note that model-based judgment is not fully devoid of emotions, as values must still be attached to outcomes (Greene, 2023; Patil et al., 2021).

In our opinion, this also explains why certain crimes are called malum in se, i.e., “evil or wrong in themselves.” They simply feel intrinsically wrong, because our emotional processes have had (cumulative cultural) evolutionary “experience” with them for millions of years (Coppelmans, 2024; Winter, 2024. See also Greene, 2013; Sznycer and Patrick, 2020).

Unrelated to criminalization, the same “evolutionary mismatch” argument is made by Gigerenzer (2000) and Jones (2001). Greene (2017) reframed his argument in terms of “the bad data and bad training problem”. And again, “experience” means experience based on genetic, cumulative cultural and individual learning mechanisms (Henrich and Muthukrishna, 2021).

See also Footnote 13. We define bias as an (unconscious) systematic and specific deviation in our cognition from a certain norm, in this case the norm being the actual harmfulness of behavior when evaluating criminalization decisions. In general, the ‘norm’ can refer to (a) an individual’s personal goals or motives, (b) the objective truth, or (c) another normative model such as the rules of statistics, logic or in this case: a legal principle (see also Kahneman, 2011).

“Harm” is a concept that can be interpreted in a multitude of ways (Feinberg, 1984; Hart, 1963; Simester and Von Hirsch, 2011). In this context, We refer to harm as a direct or potential infringement on (the interest of) one’s body or property. Yet, harm can be defined in much broader terms such as “harm to society”, “harm to familial institutions”, or “harm against public morals”. However, we believe it’s more beneficial to refrain from such expansive definitions of harm, especially given the risk that our brains might construct rationalizations for our emotionally-driven moral preferences.

This descriptive finding could have normative implications. It can introduce a so-called debunking argument (Königs, 2022), following the normative question: should we trust our affective and emotional processes (and the accompanying rationalizations) when evaluating “modern criminal offenses”? And, if not, are we willing to debunk our legal reasoning and exclude our (unconscious) emotional reactions from our argumentation, possibly leading to a different moral evaluation (Coppelmans, 2024; Winter, 2024; Greene, 2013, 2014; Singer, 2005)? This way, a “dual-process” perspective on criminalization could have descriptive and normative implications, offering many opportunities for further research in criminalization theory—both empirically and theoretically.

For example, other child-related scenarios could be “hitting a child” for the high harm low-disgust scenario (at least in terms of purity-related disgust), whereas a child dressed in an unconventional way could be a low-harm low-disgust control scenario. Gratitude is owed to Reviewer 1 for this valuable suggestion.

We extend our gratitude to Reviewer 2 for this insightful recommendation.

One could argue that, throughout history, there have been instances of marriage and sexual relationships between adults and children as young as 10 years old. However, it is not known if sexual relationships with very young children under the age of ten were ever considered acceptable practice. It is very well conceivable that the human affective and emotional reactions have evolved to strongly react against such behavior.

At least not very realistically and digitally virtual.

Again, “learning” refers to the process of acquiring skill and knowledge through a complex combination of genetic mechanisms, cumulative culturally evolved mechanisms and social/individual learning mechanisms: they all reflect “trial-and-error learning”, it is only the time scales and transmission mechanisms that differ (Greene, 2017; Henrich and Muthukrishna, 2021).

In somewhat other terms, Miller (1997) made the same argument claiming that under the influence of disgust, we too readily blame persons for deformities of character over which they have no control.

Again, for the purposes of this discussion, we will assume that the harm caused by virtual child sexual material is low, based on current literature. The primary objective is to demonstrate the influence of emotion on criminalization decisions, and how it could potentially lead us astray. If research clearly shows that virtual child pornography leads to harmful behavior, then obviously it should be a criminal offense.

Of course, there are other justifications for criminalization, such as the moral wrongfulness or obscenity of the material. However, and crucially, the lawmakers mentioned above did not consider these grounds, they specifically referred to the harmfulness of the behavior, making it possible for a criminalization bias to be present.

For instance, to be consumed only within secure online environments and with a prescription from a medical specialist. Of course, only when there is absolutely no involvement of actual children.

As is done by the United States in the PROTECT Act 2003, section 1466A (see also Bell, 2012; Bird, 2011; Miller v. California, 1973). Philosophically, the question is whether mere offensiveness is a sufficient ground for criminalization (Feinberg, 1985, 1988). However, this goes beyond the scope of this article. For now, our goal is simply to illustrate the potential impact that empirical moral psychology may have on our legal-ethical thinking and on normative questions surrounding criminalization.

They embody not only empirical tools, but also theoretical tools, such as work on affective and emotional processing in moral judgment (Haidt, 2012; Greene and Young, 2020), dual-process thinking (Greene, 2013, 2023), the evolutionary origins of morality (Joyce, 2007; Greene, 2013; Sznycer and Patrick, 2020), model-based and model-free reinforcement learning (Cushman, 2013), biases and heuristics (Kahneman, 2011), rationalization (Cushman, 2020; Haidt, 2001) and debunking argumentation (Greene, 2014; Königs, 2022). For an overview, see Coppelmans (2024).

References

Aarøe L, Petersen MB, Arceneaux K (2017) The behavioral immune system shapes political intuitions: why and how individual differences in disgust sensitivity underlie opposition to immigration. Am Polit Sci Rev 111(2):277–294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000770

Abrams KR, Keren H (2010) Who’s afraid of law and the emotions? Minn Law Rev 94(6):1997–2074

Ackerman JM, Hill SE, Murray DR (2018) The behavioral immune system: current concerns and future directions. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 12:e12371. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12371

Adolphs R, Anderson DJ (2018) The neuroscience of emotion: a new synthesis. Princeton University Press

Alces PA, Sapolsky RM (2023) All too human morality. Online publication. The MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience (Newsletter)

Alexander L, Sherwin E (2021) Advanced introduction to legal reasoning. Edward Elgar Publishing

Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition 2002, 122 S.Ct. 1389

Atari M, Haidt J, Graham J, Koleva S, Stevens ST, Dehghani M (2023) Morality beyond the WEIRD: how the nomological network of morality varies across cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol 125(5):1157-1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000470

Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, Bates DM (2008) Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J Mem Lang 59:390–412