Abstract

Researchers have long problematized the prevalence of Eurocentrism in modern Western translation theory. Alternative theories have been developing across many contexts, including China. This review examines 153 theory-related articles in four leading indexed Chinese journals that publish studies on translation. We analyzed the selected articles to explore the patterns in the development of Chinese translation theory through the past decade. Our analysis identified three characteristics of the development of Chinese translation theory: (1) Chinese translation theory developed under a heavy Western influence; (2) translation theories developed by translators; and (3) "theory"-related theoretical development on translation. These insights may help readers who do not have direct access to translation studies published in the Chinese language to better appreciate evolving translation theories that may counteract the inadequacy of Eurocentric approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Western translation theory has long been recognized as being problematic and inadequate due to its Eurocentric nature. For instance, Maria Tymoczko warns that “Eurocentric translation theory” that is permeating non-Western countries is a “form of intellectual hegemony that needs to be reconsidered and ... resisted” (2014). She further suggested translation researchers to undertake an interrogation on “the basis of the differences that exist between dominant Western assumptions and other local knowledges and experiences, differences between Western histories of translation and other local histories” (2014). This explains Shadrin’s calls for a “truly international character of translation studies” (Shadrin, 2018). Scholars based in the Western world have shown keen interest in Chinese thinking on translation theory. For example, Jeremy Munday has observed that there has been “increased interest from the West in Chinese… writing on translation” that has “highlighted some important theoretical points” (2001). This makes Chinese discourses on translation a promising place for scholars from the West to conduct new theoretical explorations and resist the Eurocentric tradition.

This article reviews the alternative theories that are being developed in China (2012–2022), as an example of “the thinking of non-Western peoples”, as Tymoczko terms it (2014). Although there is a general belief that contemporary Chinese translation theory development necessitates a rejection against Eurocentric modes of thinking, the current review is more aimed at presenting the recent developments of Chinese translation theories than an investigation into how they move beyond Eurocentric tradition. In other words, this review is not meant to look for in the reviewed articles a form of paradigm, a mindset or a set of conceptual tools that specifically go against the Eurocentric modes of thinking. The review aims to familiarize readers with an understanding of the Chinese traditions of translation discourses and theories.

Theories in translation studies have developed rapidly in China over the past decade, largely driven by two factors. The first factor is the country’s burgeoning translation industry, which can be divided into specialist translation, in the context of ever-growing international communications in commercial, legal, medical, and technological areas (i.e., specialist translation), and literary and cultural translation. Many translation activities in China have received generous financial support from the Chinese government. An important example of such government-sponsored translation initiatives is the launch of the Translation of Chinese Academic Works into Foreign Languages Program in 2010. The increasing emphasis on the role of translation in service-oriented professions and in literary and cultural discourses is not to be understood only in terms of the practical values of translation, but also in terms of the fact that translation has always constituted an important area of academic interest and theory development. The boom in translation activities has motivated translation researchers to construct theoretical models or frameworks that can appropriately describe, explain, and guide the dynamics of translation practice in the Chinese context. As Tan Zaixi has suggested, although the practice of translation does not depend on theory for its existence, its practice has always led to the development of theory (2020).

The second contributing factor to the development of translation theory in mainland China is related to its role in strengthening the growth of translation studies as an academic discipline (Zhao, 2021). Translation studies has achieved high status in the hierarchy of academic disciplines in China, and universities offer a variety of degree programs in translation studies, including undergraduate, postgraduate, and doctoral degrees. As Mu Lei points out, however, institutional progress is only one part of China’s “disciplinary construction of translation studies”, which also includes “theoretical building,” an area in need of “more efforts” (2018). Indeed, translation studies in mainland China are advancing so rapidly that there has been a massive growth in the number and variety of approaches of academic papers seeking to systematically explore and deal with major theoretical issues.

Between 1995 and 2015, for example, China’s CSSCI journals that concern translation studies published 6433 papers, which is significantly higher than the 4694 papers published by the translation journals indexed in SSCI or A&HCI (Wang and Chen, 2017). The key search term “theoretical studies” for these Chinese journals receives a higher percentage of searches than any other keywords, including “translation criticism,” “translator,” “translation teaching,” and “translation strategies” (Hu, 2020). As revealed by Liu Hu’s (2021) bibliometric analysis of articles on Chinese translation theories published with Chinese Translators Journal (2000–2019), articles on Chinese translation theories (本土翻译理论) have been growing steadily in number from 2000 to 2011 and exceeds the number of articles on Western translation theories in 2012 (2021). Similarly, we found that along with introducing Western theories on translation, these contemporary theoretical explorations (2012–2022) have been committed to rediscovering the merits of traditional Chinese translation theories,including those developed by eminent historical translators In addition,translation scholars reread and draw upon traditional discourses in areas of Chinese philosophy,cosmology,and artistic expression in order to generate original theories on translation that can be considered “Chinese” in nature.

Furthermore, we found that some papers present research findings with the intention of reframing Western theories in the Chinese context, so that they are developed into “new” theories that address new issues. In short, Chinese theoretical development in translation has been advancing fast and prolifically, and in its own particular ways that are intimately associated with China’s intellectual traditions. For this reason, we reviewed 153 studies on Chinese translation theory published in four leading Chinese journals between 2012 and 2022 in order to explore and describe how translation research is delivering original and innovative theories that are buttressing the rise of translation studies as a developing academic discipline in China’s mainland. In particular, we focused on the following research question:

What are the characteristics of contemporary translation theory development as documented in the Chinese translation studies for this review?

Answering this question is made more exigent by the fact that translation researchers mostly publish in Chinese; therefore, their research is not “readily accessible to their Western colleagues who generally do not read Chinese” (Han and Li, 2019). Given that translation studies inevitably involve at least two languages (English and Chinese in this case), the language barrier can create a significant loss of knowledge for the international community of translation studies. This loss undermines the collective efforts of translation researchers to maintain the international character of translation studies in an increasingly globalized world. It is important, therefore, to provide a review of relevant studies on these alternative translation theories in mainland China so that the insights and perspectives of Chinese researchers may be better appreciated for more profound and positive engagement with their contemporary Western counterparts. Despite this, we are aware that scholars in mainland China do publish on international English-language journals, demonstrating the global influence of Chinese theories in international translation studies. However, our search on databases of Scopus, Web of Science and Proquest returns a very limited number of articles that specifically deal with Chinese translation theories. These articles relate to the Chinese translation theories covered in the current review, including Eco-Translatology (An, 2016) and Xu Yuanchong’s “three beauties” theory (Xia and Jing, 2018; Lei and Liu, 2021).

The review

As mentioned above, this review included translation studies published in major Chinese-language journals in mainland China. Additionally, in order to focus on quality contributions of Chinese researchers, we restricted our review to studies published in journals included in the China Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) database. The CSSCI index is used by most institutions of higher education in mainland China as a means to evaluate the performance of university researchers. We identified four leading journals related to translation studies, each with a high impact factor in the CSSCI system (see Table 1). Two of these four journals, Chinese Translators Journal and Shanghai Journal of Translators, are the only CSSCI journals that exclusively focus on translation studies. The other two, namely, Foreign Languages and Their Teaching (17 articles) and Foreign Language Teaching (20 articles) were selected because they published more articles involving translation studies between 1995 and 2015 than any other journal not specific to translation studies, according to the statistics collected by Wang Feng (2018). We found that since 2015 these journals’ interest in publishing articles on translation has continued unabated. 68 articles from Chinese Translators Journal (中国翻译) and 48 from for Shanghai Journal of Translators (上海翻译) are included in this review; these comprise all articles published in these journals between 2012 and 2022. We also identified 17 relevant articles from Foreign Languages and Their Teaching (外语与外 语教学), and 20 from Foreign Language Teaching (外语教学) published within the same time period. In total we obtained 153 articles. (Table 2)

In addition, we decided to focus on articles published between 2012 and 2022 because efforts to conduct research on the discipline-building of translation studies have grown significantly since 2012 (Xu Jun, 2012), in response to China’s national strategy, launched in 2011, of building a “cultural powerhouse” (文化强国) on the international stage (Xu Jun, 2012). In addition, the academic status of translation and interpreting as a discipline was officially confirmed when the Disciplines Catalog was released by the Academic Degree Committee of the State Council in 2012 (Zhong, 2020). We also established inclusion and exclusion criteria. We opted to exclude papers that focus on translators’ biographies, their attitudes to translation, or the roles translation plays in cross-cultural transmission, and other papers that do not emphasize theoretical thinking in a significant way. We also agreed to exclude papers that merely explain Western translation theories for a Chinese audience, but we included papers, which use Western theories to inform the development of Chinese theory.

In deciding what exactly constitutes "translation theory" for the purposes of our review, the authors used a synthesis of the following well-recognized definitions to cover as many key aspects of a translation theory:

(a) Statements which lay down guidelines about how translation should be done (Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997);

(b) Specific attempts to explain in a systematic way some or all of the phenomena related to translation (Shuttleworth and Cowie, 1997);

(c) That which “can be broken down into (1) a description of its groundwork, (2) a description of its subject matter, and (3) a set of rules” (Reiss, Hans, 2014);

Following the establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria, the first author of this review manually read the titles and abstracts of every article published between 2012 and 2022 in the four chosen journals in order to determine whether they were primarily concerned with development of Chinese translation theory. Where the title and abstract of a paper were not sufficient to determine this, the first author read the paper in its entirety. This approach was used because searching for relevant articles by keywords was determined to be impractical. Indeed, the team of authors determined that the theories studied in the reviewed articles are referred to by a wide range of terms and do not necessarily incorporate the word “theory” as part of the names or titles; for instance, “Eco-Translatology,” “Daosim,” and “Yin-Yang.” In other words, there is no overarching term(s) that cover all relevant theories. When this first step of the selection process was complete, the corresponding author checked the chosen works to determine whether they met the criteria outlined above. In cases where disputes occurred, the authors consulted with one another until a consensus was reached.

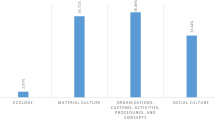

To address the research question, the first author and the corresponding author aimed to identify the characteristics of theory development in Chinese translation studies by first screening the titles of all the papers once these had been copied into a single Word document. It was discovered that a significant number (40) of papers investigate Chinese local translation theory with Western influences; this was temporarily classified as one characteristic of translation theory development. Next, we analyzed the remaining papers, in which Western influences were none-existent or minimal. Subsequently, we decided to divide this group of papers into two smaller groups reflecting two distinctly different aspects of theory development. One group, comprising 64 papers, examines translation theories by studying eminent translators. The other group, made up of 49 papers, investigates the role of mainland China’s intellectual heritage of traditional thinking about philosophy and art in the development of translation theories. The first and corresponding authors devoted a brief discussion to the determination of whether studies focusing on translators should be set apart as an independent characteristic. The result was ultimately positive, because we decided that theory development through the perspectives of translators tends to be more about ideas and concepts generated as they undertake the practice of translation, which largely differs from the insights reached through philosophical and theoretical reasoning (i.e., as characterizes the papers in the first and third groups above).

After we identified these three characteristics, the other authors double-checked them and the team eventually identified the following three categories: (1) Chinese translation theory developed with a heavy Western influence; (2) translation theories developed through translators; and (3) "theory"-related theoretical development on translation.

Characteristic 1: Chinese translation theory developed with heavy Western influences (40)

Our investigation found that the development of some of mainland China’s translation theories has been subject to significant Western influences. Due to the level of the impact these extrinsic forces have exerted, it is natural and valid to treat such formulations as a particular characteristic of the construction of mainland China’s translation theory. This general observation aligns with the research focus of the articles we reviewed. One local Chinese translation theory that has emerged and thrived following this characteristic pattern is Eco-Translatology (representative researcher Hu Gengshen), which refers to translation studies from ecological approaches (Hu, 2008). Its formulation was philosophically underpinned by Charles Darwin’s “survival of the fittest.” The central argument of Eco-Translatology, simply put, is that translation occurs in one eco-environment and the translator, as the only sentient being involved in the process, selects and adapts source and target texts in the “original eco-translatological environments” and in the “target eco-translatological environments” (Hu, 2020). Another field of research that informs Eco-Translatology is the Western ecological understanding of nature, including ecological rationality and ecological holism (Hu and Wang, 2021; Hu, 2021). The proximity of Eco-Translatology to Western theories is thus close and intimate.

Nonetheless, we feel compelled to clarify that Eco-Translatology is a distinctly Chinese translation theory; that is, it is a theory that has developed with “Chinese characteristics,” as Jiang Yan has proclaimed (2018). The Chineseness of the theory lies in its ancestral lineage and its rootedness in oriental ecological thinking and wisdom (Hu and Wang, 2021; Hu, 2021). For example, Cay Dollerup, in his Foreword to Hu Gengshen’s recent book, notes that eco-translatology is “based on ancient Chinese notions about harmony between humans and their environment (the doctrine of Unity of Man and Nature)” (2020), Liu and Zhu (2023). As some of the papers reviewed reveal below, key insights that Eco-Translatology offers in translation studies have been extracted and distilled from these ancient Chinese ideas and thoughts. It is this, then, that sustains a Chinese theory that continues to develop as an emerging paradigm with a great potential for further research and study (Valdeón, 2013; Hu, 2020, Tao et al., 2016).

40 of the studies we reviewed are primarily concerned with Eco-Translatology. Eco-Translatology takes the Darwinian concept of adaptation and selection as its theoretical foundation. In turn, this promotes a translator-centered perspective (Hu, 2008, Yue, 2019), in which the translator assumes the responsibility of selecting the most appropriate approach to translation. This notion has been taken up by Chinese scholars particularly interested in how the science of ecology can be used to study the contexts and practices of translators, who have clearly extended the concepts of selection and adaptation beyond their initial meanings. Four articles on Eco-Translatology take the translator as the primary subject of inquiry, and this theoretical perspective is useful as an approach to teaching and criticism on translation. Yue Zhongsheng also maintains that establishing the idea of translator-centeredness in Eco-Translatology is a process with layered meanings, including the translation behavior of the translator in terms of adaptation and selection (译者行为适应选择论) and the translator’s responsibility (译者责任论) (2019). Hu Gengshen notes that these two elements are connected, and argues that the translator’s responsibility falls into the category of the professional ethics of a translator (2014). Hu Gengshen proposes that a translator-centered approach in Eco-Translatology is conducive to translator training (2014) Luo, (2019).

A major theme that we observed in these 40 papers is the characterization of Eco-Translatology as an original Chinese translation theory (for instance, Wu and Zou, 2021) and the drawing of connections between its foundations and traditional Chinese concepts as “the Doctrine of the Mean” (中庸) and “the unity between man and ‘heaven’” (天人合一) (Liu, 2022). Chen Yuehong explains these concepts by highlighting a key difference between Western and Chinese conceptualizations of nature. She points out that the Western view of nature, based on Plato’s metaphysics and Aristotle’s theorization of logic, insists upon a dualistic construction on the man-and-nature relationship, but the Eastern view of nature, as Chen argues, is based on the Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist traditions and exists beyond the human-nature dualism (2015). Importantly, this human-nature/heaven relationship is one that which is interconnected (天人相通), rather than being oppositional (Liu, 2022); this is exemplified in a quote she cites from The Doctrine of the Mean: “All living beings can grow together without causing mutual harm; the ways (they choose) run parallel, rather than interfering with each other” (万物并育而不相害, 道并行而不悖, translation by the authors).

With respect to the attempts to rediscover the values of these traditional concepts in building the theoretical foundation of Eco-Translatology, this review found that Eco-Translatology relates to ecology in two ways; that is, “metaphorically” (i.e., theoretical) and “literally” (i.e., applied), with a clear focus on the former (seen in 38 papers). As noted by Antje Flüchter and Giulia Nardini, the term “‘translation’ is often used as a metaphor to problematize and explain many processes in the context of modern globalization” (2020), and Hu Gengshen has proposed a metaphor between the translation ecosystem and nature. This translation theory views humans (i.e., translators) not only as part of society, but also as part of the larger ecosystem(s) on which life is dependent. The "literal" approach is more pragmatic, and aims to provide a “new perspective to Eco-Translatogy” (Chen, 2015) and strengthen the theory’s “systematic theoretical construction” (Chen, 2022). This perspective aims to extend the theory’s subjects of inquiry to investigate actual ways of “reproducing in translation the nature views reflected in the original text” (Chen, 2015). Taking the English translation of ancient Chinese poems as an example,Chen Yuehong analyzes the linguistic and grammatical resources that translators Ernest Fenollosa and Ezra Pound adopted to recreate the “non-dualistic” view of nature. She also critiques the idea of “translational anthropocentrism,” in which translation retains or even recreates the original text’s devaluation of nature that perpetuates current ecological issues. Instead, she argues that translation can be taken as a way of raising readers' environmental consciousness (Chen, 2015) while addressing key ecological issues ranging from climate change and biodiversity loss to environmental justice (Chen, 2022).

Further, Chen Yuehong’s call for literally associating ecology with translation studies in order to address ecological concerns through translation, as revealed in her above analysis of the translation of traditional Chinese poems, has played an important role in the development of Eco-Translatology. However, we note that other case studies on Eco-Translatology in the review (7 papers) are primarily concerned with using ecology as a metaphor. These articles apply the tenets and methods of Eco-Translatology while describing or interpreting the choices made by the sentient being (i.e., the translator) who works between the ecosystems of the original and target texts. Through linguistic, cultural, and communicative perspectives, these studies focus on examining how meaning and knowledge in the original text can be communicated to and survive in the ecology of the target culture. This is reflected in Raja Lahiani’s statement that “a literary translation is... a dynamic communicative act” (2022). The contexts of these case studies are wide-ranging, including poetry (Chen, 2015), political materials (Zhang Jian, 2020), geological texts (An, 2016), and traditional Chinese medicine (Wang and Yang, 2018).

Characteristic two: translation theories developed by translators (64)

Importantly, our research found a substantial number of papers focusing on Chinese translation theories developed largely independently from Western influences. These theories shape and build upon elements of mainland China’s indigenous culture, philology, philosophy, and art, along with the intellectual achievements of renowned translators. This group of papers thus explicitly differentiates itself from the first group that we identified, i.e., that focused on Chinese translation theory developed with strong Western influences. We identified two sub-categories of articles focused on independent development of Chinese translation theories, and refer to these as characteristics 2 and 3 of Chinese translation theory development. Characteristic 2 involves theoretical development by translators, while Characteristic 3 relates to theory-related development of translation.

The formulation of translation theories drawing upon mainland China’s own theoretical resources is not completely self-contained per se, but rather is open or made open to foreign influences to limited degrees. This is due to the fact that translation researchers in mainland China are not simply copying the fruits of traditional thinking in their formulation of theories, but are rather catalyzing their own “modern reconstitution” (Feng, 2021) in order to serve the national agenda of building “modern” Chinese translation theories that can form a major part of contemporary international translation studies (Pan, 2012). This goal involves inevitable contact with the concepts and methods prevalent in Western translation research, and with shared concerns impacting the translation field globally.

However, it is important to re-emphasize the originality (and independence) of translation theory development in mainland China, particularly by highlighting the fact that the deep traditions of philosophical and artistic reasoning are at the heart of such development. This development is rooted in a range of discourses other than traditional translation theories. Thus, it can be said that the modern construction of Chinese translation theory takes on an interdisciplinary nature, integrating the essence of intellectual heritages, which are generated prolifically from varied fields of inquiry in the intellectual history of mainland China. In turn, this resonates with Hatim and Mason’s statement that in studying the complex process of translation at work, we are in effect “seeking insights which take us beyond translation itself towards the whole relationship between language activity and the social context in which it takes place” (2014). This reference to mainland China’s “own” tradition is expected, given the fact that Chinese researchers have been endeavoring to generate new ideas about translation theory and form characteristically Chinese theories, shifting their interests from “‘parroting’ [Western theories] to reconstructing past studies” (Wu, 2018) by tapping new resources for theory advancement.

Chinese researchers’ studies on translators as part of the effort in building theories in this field constitute more than half (64/110) of translation theories developed with minimal Western influences (i.e., Characteristics 2 and 3). This supports our proposal that “translation theories developed by translators” as a characteristic framework in which Chinese translation theory continues to emerge. It is important to note, however, that a given translator’s specialty and that specialty’s connection with a particular developmental path of translation also matters. Functionally, translators mediate source knowledge across cultural and national boundaries, giving them a unique position from which to understand the challenges of translation. Their perspectives also provoke them to reflect on ways to produce a “good” translation. This is reflected in Tan’s comment that although the practice of translation does not depend on theory for its existence, it has nonetheless always led to the development of theoretical thinking about the process (Tan, 2020).

In turn, translation theory shapes the translator-text relationship and highlights the significance of language, culture, and politics for translation studies, considering the translator’s biography as well as their thematic presence within the texts via the practice of translation. The attention devoted to translators in the development of Chinese translation theories underscores the fact that mainland China’s theorization on translation arises from both practice and “theories,” which are both “regarded as building blocks of ‘Chinese translation theory’” (Tan, 2020). At the same time, however, we still label Characteristic 2 as “translation theories developed by translators” rather than “theories developed through the practice of translation,” because the papers placed in this group do not specifically approach studies on translation theory through the lens of practice, but rather through the study of individual translators.

Researchers in mainland China have studied high-profile translators in order to obtain their unique insights and the esthetic and cultural values that these insights have produced. These translators are seen as the source of valuable ideas and concepts on translation that have shed light on key issues in ways that propel the progression of translation studies as a research field in mainland China. The most commonly researched translators include Yan Fu (1864–1921), Lu Xun (1881–1936), Xu Yuanchong (1921–2021), and Qian Zhongshu (1910–1998). This constitutes a scholarly focus on comparatively recent translators across the four journals selected for this study. This is surprising when taking into account of the long history of translation in mainland China, which starts in the third century with the translation of Buddhist texts by Zhi Qian, Dao An, and Kumārajīva (Tan, 2020), among others.

Theory development through studying translator Yan Fu (17 papers)

As indicated by many of the papers reviewed for this study, Yan Fu (1864–1921) is considered to be the most influential translator of his generation in the late Qing dynasty. He is admired as much for his skills as a great contemporary interpreter of Western thought as well as for the highly influential strategies and theories of translation that he summarized based on his own translations of works of Western science (Wu and Jiang, 2021). 17 papers on his theories of translation emerged through our review. As academic efforts to rediscover the merits of traditional theoretical thinking in mainland China, the papers on Yan Fu largely constitute reinterpretations of his approach to “China’s contemporary construction of translation theories” (Wu and Jiang, 2021). Research on his translation techniques and approaches focuses on describing and analyzing his actual translations, as well as the prefaces and commentaries he wrote on these translations, which offer insight into the mechanisms and dynamics of his process of translation. The most-studied account of his translation approach can be found in the foreword to his Chinese translation of T. H. Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics, and Other Essays, in which he sets out “faithfulness” (信), “communication” (达), and “literary elegance” (雅) as the three goals or challenges in achieving an ideal translation.

This primary focus in studies of Yan Fu’s work involves how the translator developed his theory: i.e., was it born from practice? And importantly, is it a product of learning from the West? Wu and Jiang have surveyed the varied arguments about how Yan’s translation theory emerged, concluding that it was developed during Yan’s practice of translation (2021), which in turn corresponds to our proposition that mainland China’s development of translation theory is driven partly by the translator’s practice of translation. Wu and Jiang also challenge the assumption that Yan’s theory is highly related to the three general rules of a good translation proposed by A. F. Tytler, instead focusing on defending the originality of Yan’s “literary elegance” (believed by some to correspond to Tytler’s “naturalness” or “ease”). Wu and Jiang argue that this concept of “literary elegance” was born from “China’s particular sociocultural conditions” (2021), as Yan drew upon the tradition of writing studies (文章学). They also note that Yan integrates the norms governing writing studies into his formation of “literary elegance,” which specifically refers to a normative and elegant writing style (雅正), intended to be read by the literati and officialdom in feudal China. In addition, Wu and Jiang propose future directions for research on translation in mainland China by highlighting the factors behind the enduring influence of Yan’s theory: for example, its rootedness in the Chinese tradition of translation studies, philosophy, esthetics, and stylistics, and its shared area(s) of inquiry with counterpart theories in the West (2021).

Jiang Lin (2015), and Huang Zhonglian et al. (2016) have explored the three main principles of translation and the relationships between them. Huang argues that communicability is at the center of Yan’s theory, and that “elegance” is a means of reaching communicability for the targeted reader of the translated text. Jiang Lin is interested in “elegance,” and notes that Yan’s elegance is his advocacy of using the language of classical Chinese for translating English-based works. In turn, Jiang maintains that this elegance is Yan’s faithfulness to his potential readers, who he imagined as “scholars versed in Chinese classics” (2015).

In our research, we found seven papers related to Yan’s concept of “communication” as it relates to Translation Variation theory (翻译变译理论), which Huang Zhonglian put forth at the turn of the 21st century. Huang takes variation to mean that the translator may try to communicate the content of the original by expanding, omitting, or rewriting certain parts of the text (2000), and these adaptive measures are usually taken to satisfy the needs of specific readers under specific conditions (Huang, 2002). Variation is contrasted with “total” or “full” translation (全译), a method that underscores the “fusion of horizons” of the “original” author and the translator who endeavors to retain the information of the original text (Zhang, 2018). Translation Variation theory was developed based on Yan’s diversified strategies and the techniques he applied in order to achieve the communicability of his Chinese translation of Evolution and Ethics to Chinese readers of the 1890s (Huang, 2016). Translation Variation theory contributes to translation studies by theoretically justifying variational translation practice from the perspective of cross-cultural communication (Huang and Zhang, 2020), and by outlining the general features and rules of the variational translation process; this includes a summary of adaptation techniques and methods such as addition, omission, editing, commentary, condensation, combination, and reformation in light of specific readers’ needs under specific conditions (Huang, 2016). As Wu Zixuan notes, founded on Yan’s theory, Translation Variation theory has become part of mainland China’s original, independently formulated translation theory (2018). This corresponds with Wu and Jiang’s above-mentioned suggestion that the reinterpretation of Yan’s approach serves mainland China’s contemporary construction of translation theories.

Theory development through studying translator Xu Yuanchong (10 papers)

Xu Yuanchong (1921–2021) is also popular with contemporary translation researchers in their efforts to advance Chinese translation theory (10 papers). Xu Yuanchong was a prolific translator, particularly renowned for translating traditional Chinese classics into English and French. Xu’s contribution to recent developments in translation theory is significant, as he “left a treasure trove on translation theory”, according to Zhang Xiping (Zhang, 2022), and Zhang Zhizhong (Zhang, 2022). Studies on Xu in the selected journals bear two striking resemblances to those focusing on Yan Fu. First, papers on Xu similarly intend to reinterpret his theories in order to, according to Zhu Yishu contribute to the “construction of translation theories that are distinctively Chinese” (2019). Second, Xu’s translation arguments are considered intimately connected to mainland China’s traditions of thinking on philosophy and translation, but are also connected to Xu’s creative thoughts regarding his decades-long practice of literary translation (Zhu, 2019; Zhu, 2020; Zhu, 2022).

A central theme of articles about Xu is the discussion of whether his theoretical ideas are informed by linguistic or literary theories. Qin Jianghua and Xu Jun, for instance, maintain that Xu embraces a linguistic viewpoint of translation in an attempt to address key linguistic issues in translation studies (2018). A specific point they raise is Xu’s disapproval of Eugene Nida’s theory of dynamic equivalence, which Xu believes cannot be applied to Chinese-English translation because of the significant linguistic differences between the two languages (2018), but which he argues can be applied to translation between Western languages as they exhibit a higher degree of similarity (2018). Contrary to dynamic equivalence, Xu proposes approaches to translation that aim for a “unity between languages in translation” (语言统一), through identifying the advantages of the target language (2018).

Zhu Yishu, in contrast, argues that Xu’s theory of translation moves beyond the level of language into a literary point of view of translation (2018). Zhu notes that, for Xu, the ultimate task for a literary translator is achieving the status of “literature” for a translated text (翻译文学2018), which then enjoys the same status as an “original” literary text does.Footnote 1 The examples of “translated literature” (in Chinese) that Xu gives include works of Shakespeare (translation by Zhu Shenghao) and Honoré de Balzac, translated by Fu Lei (2018). To achieve this goal, Xu proposes translating with creativity (Zhu, 2019), and in this way-making “translation-art” (Zhu, 2018 艺术性).

Characteristic 3: "theory"-related theoretical development on translation (49)

Classical Chinese philosophy has provided rich resources and perspectives for the development of Chinese translation theory, and has helped to shape the distinctive approaches and practices of Chinese translators. As outlined above, in Characteristic 2 the reviewed literature involves studies on the translation strategies and perspectives of eminent translators such as Yan Fu and Xu Yuanchong and their place in the contemporary construction of Chinese translation theory. These papers touch on mainland China’s considerable output of studies on philosophy and philology, which are closely associated with these individual translators’ thinking on translation. In our research, we decided to set apart these collective attainments in the intellectual history of mainland China as a separate group of papers (Characteristic 3), because traditional theoretical thinking is given only minor significance in the translator-focused studies of Characteristic 2, which does not do justice to the significant impact that these theoretical resources have had on the formulation of translation theory in mainland China.

Regarding the word “theory” in the title for this section, it is important to note that “theory"-related theoretical development on translation” refers to theories that were historically generated in mainland China in fields such as philosophy, philology, translation, or art, which are borrowed in order to develop contemporary translation theories. As mentioned previously, the term "theory" in this review is used in a broad sense, covering ideas, concepts, and theories; this is also the case with “theory"-related theoretical development on translation.” In this way, investigations into the ideas and concepts in traditional Chinese philosophy remain to be explored.

Theory development through the Dao, Yin-Yang, Qi, and other concepts

One group of papers we reviewed explore traditional philosophical concepts and how they are used by the authors of these papers to develop innovative ways of describing or explaining translation phenomena and problems. The concepts which they explore are reasonably diverse given the wealth of traditional Chinese thinking and inquiry. These concepts are sometimes discussed as being interrelated, for instance, the Dao and Yin-Yang. The research focus of these papers involves studies on Daoism and its representative work The Book of Changes (one of China’s richest and most influential works of ancient philology, Cai, 2017; Wu and Zhu, 2019), and Tai Chi (太极 martial art, Zhu 2019; Jiang, 2019). Overall, the concept of Dao has been used in different ways in translation theory, from describing the translation process to providing a standard for evaluating translation quality.Dao reflects the emphasis in Chinese philosophy on holistic and contextual understanding, and the idea that the ideal translator is attuned to the complex interrelationships between language, culture, and context (yin).

Dao is a fundamental concept of Chinese philosophy, and its role in translation studies has been heavily researched. Therefore, it exerts considerable influence over the modern development of translation theories in mainland China (Cai, 2017). When applied to translation studies, Dao takes on several definitions. For instance, it may be defined as a mysterious force that cannot be known, and as the way things happen, or a path, or way-making (Cai, 2017). Dao is also applied in different ways: as a philosophy, a process, and a standard. For instance, with Dao as a process (the interchange between Yin and Yang), Cai Xinle has argued that Dao can be used as a metaphor to describe the process of translation as a pathway whereby the translator follows the “way” that leads to an effective translation (Cai, 2016).

A striking feature of most of these explorations is that they are not conducted in a nationally isolated fashion, but manage to engage with Western critical thinking on translation. Cai Xinle (2016) applies the concept of Yin-Yang in interpreting meaning transfer in translation in terms of motion, and this, he argues, can help realize what Jacques Derrida calls the “ideal of translation” (2016). Jiang Chengzhi argues for the intertextual relation between Yin-Yang (reciprocal verbal articulation to create a mirroring rhythm in the target text) and Marin Heidegger’s idea of speaking within the language—that is, listening to the words that the language addresses, or what Roman Jakobson classifies as “inter-semiotic translation” (2019).

Wu Bing and Zhu Jianping explore the formulation and key arguments of K. A. Appiah’s “thick translation”, a style of translation that features an abundant use of annotations and glosses in order to provide context for target readers, based on the notion that “utterances depend on context for their meaning” (2019). They argue that the techniques of “thick translation” may construct a context for the translated text that departs from that of the original because of the translator’s “subjective assumptions” (2019). They instead propose that the “heart” as the site for the workings of the mind determines the validity or truth of individual cognitive processes (2019). They also note that the heart can be blinded when it is not acting according to Dao, which requires a translator to restrict worldly desires and submit to external forces in order to achieve calmness and emptiness of the heart (2019).

Theory development through drawing upon traditional Chinese painting (4 papers)

Our research found four articles on translation that focus on a particular visual art; namely, traditional Chinese painting and its relationship to the development of Chinese translation theory. These articles explore the philosophy, esthetics, and techniques of painting. Granted, the affinity between poetry and literature (and literary translation by extension) and painting is investigated in both mainland China and the West (Zhang and Liu, 2012), as revealed in Greek philosopher Plutarch’s statement that “painting is mute poetry, poetry a speaking picture,” or in Chinese poet and painter Su Shi’s (1037–1101) concept of “poetry in painting and painting in poetry.” However, the ways in which traditional Chinese painting is imagined and practiced differ from Western counterparts,as are the ways painting informs and inspires development of theory. This is the primary reason we decided to describe this group of papers as a specific subcategory under Characteristic 3 (“theory”-related theoretical development on translation), despite its relatively small number of papers. The interplay between translation and Chinese art (painting) shows great potential to “broaden the horizon of translation research” by situating translation in a broader context of traditional Chinese artistic representations (Zhang, 2022).

Zhang and Liu (2012) analyze literature in translation by using the techniques of traditional Chinese painting, including spot-dyeing (点染), the juxtaposition of images in a painting (意象并置), and the use of “multiple perspectives” (散点透视, as opposed to West’s dominant form of single-point perspective) for creating visual and discursive effects in translation. For instance, they note that Ezra Pound, when semiotically translating a painting from 潇湘八图 (literally The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang) into written words, adopts the painting technique of image juxtaposition; that is, he follows the imagist movement, creating an effect of a text running like “a series of photos, or images, or fragments, not logical in terms of forms but quite coherent” (Wang, 2019). Pound’s translation is rendered here for reference:

Rain; empty river; a voyage,

Fire from frozen cloud, heavy rain in the twilight

Under the cabin roof was one lantern.

The reeds are heavy;

bent; and the bamboos speak as if weeping (Zhang and Liu, 2012).

Zhang Baohong discusses how the ways in which colors in traditional painting represent spatial distance (Zhang, 2022) and how this can inspire fresh ideas in literary translation. He argues that color, as a unit of painting, can act as a cross-medium tool to translate distance in literature. To clarify this, he analyzes Ezra Pound’s English translation of a line of Chinese poem, “青青河畔草”. it’s the literal translation of this line is “green, green grass on the banks of the river”, but “green” is rendered as “blue” in his translation: “Blue, blue is the grass about the river.” Another example Zhang offers is a translation by Kenneth Rexroth, who also uses “blue” to translate “the mountain faraway” in another Chinese poem. Zhang believes that Pound is using the capability of blue in representing far-flung objects to communicate the hidden information that the grass is actually seen at a distance in the poem (2022). Chen and Zhong explore the space-creating techniques in traditional Chinese painting and their use in poetic translation. One of the techniques they describe is the use of three distancing perspectives (三远透视), which emphasize the creation of “psychological experience” and “mental imagery” (2017).

We have outlined above how major techniques from traditional Chinese painting are examined to help rethink the problems caused by a lack of tools for representation in translation. However, in the papers selected for this study, the points of contact between art and translation go beyond expressive skills to covering the experience of feeling or emotion (affect) and poetics as expressed in painting. As Zhang Baohong explains, when incorporating the language of painting into translation, readers are able to identify faster and more strongly with the scene and feelings expressed in the original (2022).

Theory development drawing upon traditional writing studies (文章学, 6 papers)

Our review identified six papers on “compositional translatology” (文章翻译学), a theory based, according to its originator, on Chinese writing studies, which is a “purely Chinese knowledge of learning,” (Pan, 2019). For this reason, compositional translatology is now considered a characteristically Chinese translation theory (Feng, 2021). As writing studies is concerned with theoretical and practical ideas about writing, as its name indicates, its use in formulating a translation theory essentially lies in its relevance to the relationship between writing and translation, and to the development of a “theory of translation as writing” (Pan, 2019). In a nutshell, Pan’s theory promotes the idea that “translation ought to be conducted in ways that traditional (educated) Chinese write” (Pan, 2019).

Pan Wenguo explains why he turned to writing studies, of all the Chinese traditions, to support his work toward building a Chinese translation theory (2019). He argues that the once-neglected area of writing studies is the foundation of two influential traditions in thinking about translation: one is the fierce polemics over whether form or content is more important in translation (Wen or Zhi, 文质之争) in the Northern and Southern Dynasties of China (420–589); the other, which emerged much later, focuses on the three criteria on translation put forth by Yan Fu (2019). Writing theory has been neglected in Chinese academia for the past century because it does not correspond to any concept in the repertoire of Western theories introduced into Chinese, and as a result, it was reduced to the simple study of “writing skills for middle school students” or narrowly understood as only being related to literature (2019).

Pan Wenguo goes to great length to brief the reader on the basics of Chinese writing studies before discussing the application of this field to compositional translatology (2019). He notes that writing studies in historical China were hugely important in cultural and intellectual spheres, representing, in the view of important thinker Cheng Ying (1033–1107), one of the three areas of learning in traditional China, along with philology (训诂之学) and Confucianism (2019). The theory thus covers nearly all fields of inquiry that deal with writing as its subject matter (2019), and in Pan’s opinion this distinguishes itself in a positive way with mainland China’s contemporary study on discourse, grammar, literature, rhetoric, and stylistics that are subjected to Western influences (2019).

Pan Wenguo also discusses the misperception that writing studies are merely about “ways of writing” (2019). According to Wu Chengxue, this is the implement aspect of writing studies (器), distinct from the other aspect of Dao (道) (2012). Writing studies as a field in its entirety, i.e., including the aspects of both implement and Dao, is drawn upon in the development of Compositional Translatology (Pan, 2019). In terms of implementation, Pan’s theory is put forth as a system of principles and methods to guide the practice of translation, emphasizing the ornate style of “writing” for the translated text (重文采) and the use of principles of Qi in translation.Footnote 2 In turn, Qi can be embodied in the harmonious, rhythmic combination of letters, words, and sounds within a text (Pan, 2019). As for Dao, Pan notes that in the tradition of writing studies, the character (integrity) of a human being (the writer) should be fostered prior to the act of writing (“为人先于为文” 2019). This points to the aforementioned debate on the relative priorities of form and content, and to Yan Fu’s criteria, as giving prominence to the expression of Confucious/Dao-informed content in translation is related to the cultivation of the integrity of the writer as a human being through learning Dao. Similarly, Pan argues that Yan Fu’s principles on translation are an indication of how he treats translation ethically and responsibly (“译事三难”).

Conclusion

In this review, we have aimed to address the following research question: What are the characteristics of contemporary translation theory development as documented in the Chinese translation studies for this review? There have been remarkable achievements in mainland China’s long history of studies on translation, and they continue to be used to drive theoretical developments in translation in modern China. To quote Tan Zaixi, the renowned Chinese translation theoretician, there exists “both a Chinese tradition of studying and discussing translation, and a Chinese legacy of theoretical ideas about translation” (quoted in Han and Li, 2019). We have addressed this question by surveying 153 theory-related papers identified in four leading CSSCI-indexed journals that exclusively or largely concern translation. In our review of these papers, we found that significant research efforts have been made to theorize translation in the past decade, in order to guide the practice of vocational, service-oriented, and literary translation, as well as to provide theoretical inputs to translation research that can propel academic disciplinary growth in mainland China.

Through this research, we found that the traditional theories on translation covered in the 153 papers mostly are approached through the study of notable translators (i.e., Characteristic 2: translation theories developed through translators). Important examples of such translators include Yan Fu and Xu Yuanchong, who are renowned for having made significant contributions to the development of Chinese translation theory in the past two centuries. Their ideas continue to be employed in the formulation of contemporary theory.These translators developed their theories based on their personal experience and observations accumulated in the practice of translation. As Tan Zaixi maintains, the history of translation reveals that the practice of translation in the Chinese tradition, as in other translation traditions, has contributed to the development of theoretical thinking about the practice of this activity (Tan, 2020). These translators also drew upon the rich traditions of Chinese philosophy and literature, which have provided a wealth of materials for translation practice and personal reflections.

In addressing the research question, we found that the theoretical resources used by translators go beyond the field of translation to include classical Chinese philosophy, philology, language, and arts, which have all had a significant impact on the formulation of translation theory in modern China. We refer to this wider theoretical influence as Characteristic 3; that is, "theory"-related theoretical development on translation, in contrast to to Characteristic 2, development through translators. The emphasis on harmony and balance as represented in Chinese philosophy, such as the Confucian concept of Dao, has shaped the ways in which translation theories continue to be conceived and developed. Furthermore, we found that Chinese translation theory has developed through an engagement with Western translation theories, as in the case of Eco-Translatology (Characteristic 1: Chinese translation theory developed with heavy Western influences).

In this review, we have identified and analyzed the characteristics of recent developments in translation theories in mainland China in the period between 2012 and 2022. It is our intention that the international translation community may benefit from greater understanding of these approaches and perspectives, which have been shaped by the particular historical and cultural context of mainland China. In addition, this review is part of a larger effort throughout the field of translation studies to combat the dominance of Eurocentric approaches and develop a truly international translation studies field. It is also worth noting that individual translators have attracted surprisingly little attention in the West (Dam and Zethsen, 2009), in contrast to the way in which mainland China’s translation theory often focuses on the translator—those who generate the translated texts and engage with the translation process. By introducing this approach to the translation studies field beyond mainland China, we hope to offer fresh insight into the production of an “ideal” translation.

Data availability

A supplementary excel file named “data” is uploaded with the paper.

Notes

In the European tradition, there exists a perceived, essentialist hierarchy between so-called “originals” and “translations,” believing that translation derives from the original literature and is reduced to a lower literary status (see for example, Alice Leal, 2016).

Qi roughly refers to a vital energy or force that permeates the human body and the universe.

References

An J (2016) The adaptive conversions in translating geology texts from the perspective of Eco- Translatology. Shanghai J Transl 6:28–32. 93

Cai X (2016) The Daoist perspective on the translation of “writing by ancient Chinese literati”. Chin Transl J 5:81–87

Cai X (2017) “Yin-Yang” and “Emergence” in translation - a critique on Qian Gechuan’s Fundamental Knowledge on Translation. Shanghai J Trans 4:1–8. 94

Chen Q, Zhong W (2017) How Liang Zongdai’s French translation of Les poèmes de T'ao Ts’ien is similar to painting. Foreign Lang Teach 1:80–85

Chen Y (2015) Eco-translatology as a new perspective – on the Eco-Translatological turn in the English translation of Chinese poems. Foreign Lang Teach 2:101–104

Chen Y (2022) Ecological Concerns and the Literal Sense of Eco-Translatology: current situation and directions. Chin Transl J 4:13–21, 190

Dam HV, Zethsen KK (2009) Translation studies: Focus on the translator. Hermes J Lang Commun Stud 42(1):7–12

Feng Q (2021) Chinese translation theories: an overview and future visions. J Zhejiang Univ (Humanities and Social Sciences) 1:163–173

Flüchter A, Nardini G (2020) Threefold translation of the body of Christ: concepts of the Eucharist and the body translated in the early modern missionary context. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(1):1–16

Han Z, Li D (2019) Translation Studies as a Young Established Discipline in China. In (eds) Translation Studies in China, Springer Singapore

Hatim B, Lan M (2014) Discourse and the Translator. Routledge

Hu G (2008) explaining Eco-translatology. Chin Transl J 6:11–15. 92

Hu G(2014) From “translator-contentedness” to “translator duties” Chin Transl J 1(29–35):126 126

Hu G (2020). Eco-translatology: Research foci and theoretical tenets. In: Hu Gengshen, Eco-Translatology: Towards an Eco-paradigm of Translation Studies, Springer Singapore, p

Hu G (2020). Foreword by Dollerup. In: Hu Gengshen, Eco-Translatology: Towards an Eco-paradigm of Translation Studies, Springer Singapore, p v - vi

Hu G (2021) Theoretical innining Eco-tranining Eco-tranmination. J Zhej Univ (Humanities and Social Sciences) 1:174–186

Hu G, Wang Y (2021) Orientation, meaning and features: Eco-Translatology as a research paradigm. Foreign Lang Teach 6:1–6

Huang Z (2000) Study on translational variation. China Translation Corporation. Beijing

Huang Z (2002) Theories on variation. China Translation Corporation. Beijing

Huang Z (2016) The essence of Yan Fu’s system of translation theories – a study on his variation theory. Chin Transl J 1:34–39

Huang Z, Zhang Y (2020) Variational Translation Theory. Springer, Singapore

Jiang C (2019) “Pushing-hands” in translation studies – from the perspective of Martin Heidegger. Chin Transl J 2:17–27. 190

Jiang L (2015) An investigation into Yan Fu and Liang Qichao’s arguments on translation. Chin Transl J 2:26–30. 128

Jiang Y (2018) studies on characteristically Chinese translation theories. J Lanzhou Univ Arts Sci 3:116–120

Lahiani R (2022) Aesthetic poetry and creative translations: a translational hermeneutic reading. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–9

Leal, A. (2016). Translation at the European Union and English as a Lingua Franca: Can erasing language hierarchy foster multilingualism?. New Voices Transl Stud, (14)

Lei P, Liu Y (2021) Analysis on the Translation of Mao Zedong’s 2nd Poem in “送瘟神 ‘sòng wēn shén’” by Arthur Cooper in the Light of “Three Beauties” Theory. Theory Pract Lang Stud 11.8:910–916

Liu A, Zhu Y (2023) From fellow traveller to eco-warrior: the translation and reception of Thoreau in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–9

Liu H (2021) Review of Chinese Translation Theories (2000- 1029) - with bibliometric analysis of articles on Chinese translation theories published with Chinese Translators Journal as an example. Foreign Stud 2:80–88

Liu J (2022) The three core philosophical values and functions of Eco-translatology. Shanghai J Transl 1:1–8. 95

Luo D (2019) Change of approaches to approaches in translaiton studies: the perspective of Eco-translatology. Chin Transl J 4:34–41

Mu L (2018) Exploring the building of the discipline of translation studies. Chi Transl J 6:9–11

Pan W (2012) Chinese translation theories and Chinese discourse. Foreign Lang Learn Theor Pract 1:1–7

Pan W (2019) The name and nature of compasitional translatology. Shanghai J Transl 1:1–5. 24, 94

Qin J, Xu J (2018) Interpreting the linguistic views in Xu Yuanchong’s translation theories. Foreign Lang Teach 6:118–125. 147-48

Reiss, K, and H J. Vermeer (2014). Towards a general theory of translational action: Skopos theory explained. Routledge

Shadrin VI (2018) On Eurocentrism in modern translation theory. International Information Institute (Tokyo). Information 21(3):937–949

Shuttleworth, M, and M Cowie (1997). Dictionary of translation studies. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing 192:193

Tan, Z (2020) Chinese Translation Discourse—Traditional and Contemporary Features of Development. In: Lily Lim, Defeng Li (eds) Key Issues in Translation Studies in China: Reflections and New Insights, Springer Singapore, p 1–27

Tao Y, et al. The fusion of Western and Eastern ecological wisdom in Journal of Eco- Translatology – proceedings of the fifth international conference on Journal of Eco- Translatology. Chin Transl J 2:74–77

Tymoczko, M (2014). “Reconceptualizing translation theory: integrating non-Western thought about translation.” Translating Others (Volume 1). Routledge. 13–32

Valdeón, R. (2013). An emerging paradigm with a great potential for research and study-message from Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. J Eco-Translatol, p. 1–2, 8-10

Wang C, Yang Y (2018) Study on English translation in hospital public signs from the perspective of Eco-translatology. Shanghai J Trans 4:39–43

Wang F, Chen W (2017) Hotspot and trends at home and abroad - a knowledge mapping analysis based on core translation journals. Foreign Lang Teach 4: 83-88

Wang G (2019) Translation in Diasporic Literatures. Springer, Berlin

Wu B, Zhu J (2019) Complementary thoughts on thick translation from the perspective of theory on mind in Dao. Chin Transl J 4:143–149. 190

Wu C (2012) Emergence of Chinese traditional writing studies and the rise of studies on ancient literature. Soc Sci China 12:138–156. 208-09

Wu G, Jiang Y (2021) Research on the original of Yan Fu’s faithfulness, communicability and literary elegance and an reinterpretation for their significance in translation studies. Chin Transl J 3:50–56. 191

Wu J, Zou M (2021) Reflections on some issues of Eco-translatology. Shanghai J Transl 5:17–22

Wu Z (2018) Variation theory and the construction of Chinese school translation theories. Shanghai J Transl 4:75–77. 62, 95

Xia C, Jing Z (2018) English translation of classical Chinese poetry. Orbis Litterarum 73.4:361–373

Xu J (2012) Discussing translation studies and its disciplinary building from the perspective of national cultural progress. Chin Transl J 4:5–6

Yue Z (2019) Ecological being of the translator and “translator-centedness”. Shanghai J Transl 4:14–18. 94

Zhang B (2022) The creative use of the painting language in literary translation. Chin Transl J 1:150–157. 189

Zhang B, Liu S(2012) Borrowing elements of painting in literary translation. Chin Transl J 2:98–103

Zhang J (2020) Communicative effectiveness of translating political materials from the perspective of Eco-translatology 4: 52-56

Zhang T (2021) Movie subtitle translation from the perspective of the three-dimensional transformations of eco-translatology: a case study of the english subtitle of lost in Russia. J Lang Teach Res 12 1:139–143

Zhang X (2022) Xu Yuanchong’s Translations and Their Value. In: (Zhang X. ed) A Study on the Influence ofAncient Chinese Cultural Classics Abroad in the Twentieth Century. Singapore: Springer Singapore, p 215-224

Zhang Y (2018) Effectiveness on international cultural communication in terms of cultural Variational translation and full translation. Shanghai J Transl 4:78–82. 95

Zhang Z (2022) On the theory and practice of Xu Yuanchong: contributions and restraints. Chin Transl J 4:92–97

Zhao T (2021) The three turns in translation studies against the background of building translation studies as a discipline. J Xingtai Univ 1:146–152

Zhong, W. (2020). Recent Development and Future Directions of Translation and Interpreting Education in mainland China. Translation Education: A Tribute to the Establishment of World Interpreter and Translator Training Association (WITTA), 83-97

Zhu C (2019) The Yin-Yang poetics in translation – the pushing-hands, qi and pure language. Chin Transl J 2:5–16. 190

Zhu Y (2018) From linguistic to literary translation – analysis on Xu Yuanchong’s artistic view on translation. Foreign Lang Teach 6:126–132. 148

Zhu Y (2019) On the characteristics of Xu Yuanchong’s translation theories. Shanghai J Transl 5:83–87. 95

Zhu Y (2020) An analysis on the “Chinese roots” of Xu Yuanchong’s translation theories. Foreign Lang Teach 3:94–98

Zhu Y (2022) Translation art and creativity in translation – on Xu Yuanchong’s aesthetic pursuits in translation. Chin Transl J 3:89–97

Acknowledgements

This article is funded by the following project: 重庆市教育委员会人文社会科学研究一般项目 “华莱士·史蒂文斯译介与中国新诗的互文性研究” (19SKGH221) (Translation of Wallace Steven’s and Chinese New Poetry: from the Perspective of Intertextuality (19SKGH221), Humanities and Social Science Research Project of Chongqing Education Commission).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, Z., Cui, X.(. & Gao, X.(. The characteristics of contemporary Chinese translation theory development: a systematic review of studies in core Chinese journals (2012–2022). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 596 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01955-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01955-w