Abstract

Cultivated and plant-based meats are substitutes for conventional animal meat products. As radical innovations, they may trigger profound social and economic changes. Despite the many benefits of alternative meats, such as environmental sustainability, animal welfare, human health and food safety, some unintended consequences remain unexplored in the literature. In this paper, we studied the potential impact of the meat production system transition on jobs. Using a survey, we compared opinions regarding the impact on jobs in Brazil, the United States and Europe, according to alternative protein experts. Our results showed the potential of plant-based and cultivated meat production to create new and higher-skilled jobs. The data analysis also suggested that the impact of novel food production systems on jobs in conventional meat production may be different for each stage of the value chain. In particular, the results showed a pressure point on animal farmers, who may be most affected in a fast transition scenario. Considering the studied geographical contexts, Brazilian professionals were more optimistic about the potential of plant-based and cultivated meat production to create new jobs. Our findings may provide new insights for the development of policies, measures and strategies that promote job creation, skills and income in view of the ongoing transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last 50 years, global food consumption has quadrupled and the world human population has consumed on average twice as much meat as the previous generation (Weis, 2015). The overconsumption and overproduction of meat has led to an unbalanced and harmful relationship between the food industry and the environment, for example soil depletion, intensive use of water and climate change (Tuomisto and Teixeira De Mattos, 2011; IPCC, 2020; Eisen and Brown, 2022), as well as between the food industry and animal ethics (Heidemann et al., 2020a).

In this scenario, in which there is a need to move towards more sustainable food production that goes beyond animal agriculture and is not supported by animal slaughter (Herrero et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2021), alternative meats are emerging as promising solutions. Through disruptive innovations and new technologies that significantly change the sociotechnical production paradigm (Perez, 2010), alternative meat production is looking for other ingredients, processes, and products to change this reality (Gerhardt et al., 2020; Reis et al., 2020a; Carolan, 2020). Alternative meats are substitutes for conventional animal meat products and are provided through innovative food processes and technologies (Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021; Onwezen et al., 2021). Plant-based products mimic the taste, texture and flavour of conventional meat and may act as a direct meat substitute, with no animal ingredient (Cameron and O’Neill, 2019; Rubio et al., 2020). Cultivated meat is part of a broader movement called second domestication of animals, in which meat is produced using cell reproduction technology (Reis et al., 2020a; Tubb and Seba, 2020; Post et al., 2020). These new practises, which are generally viewed positively (Stephens et al., 2018), may bring about significant changes in the conventional meat system. Key benefits of alternative meats include issues of environmental sustainability, animal ethics and welfare, human health, food safety and food security, as well as increased efficiency throughout the meat supply chain (Tuomisto and Teixeira De Mattos, 2011; Heidemann et al., 2020a). Furthermore, projections of increasing demand for meat and its inputs, as well as the negative impacts of the conventional meat chain in terms of resource use (e.g. land, water), animal ethics (e.g. rearing and killing of animals), waste, among others, make the debate on alternative meat urgent and relevant (Weis, 2015; Willett et al., 2019; Reis et al., 2020a).

This study focuses on the transition to a scenario in which alternative meats become the source of a considerable share within protein production and consumption systems. Furthermore, we draw on the sociotechnical transition theory literature, which seeks to understand how society’s needs are met and the profound changes that may occur from any substantive transformations in technological systems (Schot and Geels, 2007; Geels, 2020). Such transformations may affect, for example, the way businesses, supply networks and market infrastructure are organised, as well as ignite in social and economic domains (Sorrell, 2018). Several studies are currently undertaken to address the transition to more sustainable and ethical food production systems, such as research on the use of energy based on clean sources for a low-carbon future (Hirt et al., 2020; Johnstone et al., 2020), on the reuse of raw materials through processes based on the bioeconomy (Conteratto et al., 2021), and on the ethical treatment of animals (Soriano et al., 2021; Heidemann et al., 2020a).

While the transition from conventional to cultivated and plant-based meat appears to be a desirable near future from the perspectives of sustainability, public health, food safety and animal welfare, it remains open to several plausible pathways to become a reality (Stephens et al., 2018; van der Weele et al., 2019; Morris et al., 2021; Nobre, 2022). Some potential drawbacks of this transition have been explored in the literature. For instance, the possibility of complementarity rather than substitution across production chains given the projected steady increase in demand for meat, where total meat production only adds up, i.e., an additional effect between conventional and alternative meat, which in turn does not allow the expected environmental benefits to be achieved (Stephens et al., 2018). Another scenario may be characterised by an accelerated transition to meat produced from alternative protein sources, bringing up unintended consequences (Herrero et al., 2011) such as social degradation in meat-producing countries through job losses (Reis et al., 2020a) and a widening economic disparity between countries, e.g. between producer and consumer countries (Mouat and Prince, 2018; Santo et al., 2020; Chriki and Hocquette, 2020). For example, Tubb and Seba (2020) find that because of the food system transition, half of the 1.2 million jobs in US conventional beef and dairy production and related industries will be lost by 2030, rising to 90% by 2035.

The production of cultivated and plant-based meat involves the introduction of new production processes, new types of input, new actors and technological developments throughout the chain. These radical innovations can trigger profound changes in the meat industry as a whole (Reis et al., 2020b; van Hout, 2020). Therefore, there is a need for zooming-out analyses for the transition to alternative meat, including unintended and unforeseen consequences (Mattick et al., 2015). In this study, given the likely shift in the meat value chain (Herrero et al., 2011; Gerhardt, et al., 2020; Tubb and Sena, 2020), we aimed to understand the social impacts of cultivated and plant-based meat production in Brazil, the United States and Europe. More specifically, we studied the potential impact of the transition to a meat chain based on cultivated and plant-based meat production systems on the workers employed in different positions of the conventional meat supply chain, considering multiple ways and degrees that may characterise such transition.

Methodology

Research design

To explore the potential impact of the transition to a meat chain based on cultivated and plant-based meat production systems on the labour force, we interviewed experts from the conventional and alternative protein landscape in three localities: Brazil, the United States and Europe. Studies that draw on expert knowledge may help understand issues about which little information is yet available (Bogner and Menz, 2009) or even help predict possible futures, for example in the face of technological change (Haleem et al., 2019). In this way, the perspective of experts can shed light, albeit partial, on the opportunities, challenges and consequences that the shift in meat production may bring in terms of jobs, income and skills.

We targeted these three specific geographic regions because they are the major exporters of animal products in the globe (Tubb and Seba, 2020) and also because of the potential impact and importance that such transition can have to the workforce in these regions. Specifically, in Europe we chose experts from six different countries, i.e., Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and The Netherlands, seeking a more representative sample for the region.

Data collection

In this study, expert sampling (Frey, 2018) was used to identify and select those who were involved, in some way, with alternative or conventional meat chains, and with significant and demonstrable expertise in animal production and alternative meat production. We divided these experts into four large groups based on their affiliation and professional expertise as shown in Table 1:

The identification of potential respondents followed multiple paths. We initially identified 416 industrial experts situated in the geographic scope of the research from the list of alternative meat companies on The Good Food Institute (GFI) website. We sent an invitation by the email available on the GFI’s list and actively contacted people from these companies through social media. Additionally, we identified 165 scholars from publications in the field of cultivated and plant-based meat that were registered on the Web of Science (see e.g., Fernandes et al., 2021a for a bibliometric review) and contacted them by the email stated in their publications. We also looked for experts from third sector organisations related to alternative protein, such as people from NGOs, and government and regulatory bodies working on alternative proteins. Finally, we used the authors’ contacts to approach additional potential experts not contacted by the previous methods. We also asked our respondents to share the questionary link with experts in the field from their own professional network.

Through these approaches, we contacted a total of 879 experts, received 217 responses from the questionnaire sent, and validated 161 fully completed. We excluded 25 responses from countries out of our geographic scope. Therefore, we achieved 136 complete responses from our target countries, which composed the final sample of this research. Of all respondents, 25.7% were from Brazil, 33.1% from the United States and 41.2% from Europe (9 from Belgium, 12 from France, 7 from Germany, 10 from Italy, 7 from Poland and 11 from The Netherlands). Table 2 provides more details on the respondent characteristics and self-judged expertise.

The research instrument was developed with multiple five-point Likert scale questions and open-ended questions based on a qualitative study carried out previously by three of the authors, in which the significant potential social consequences were explored (see Morais-da-Silva et al., 2022), as well as in the relevant scientific literature. The questionnaire covered questions about the impact of alternative meat production on jobs in the conventional meat industry, the professional qualification necessary for the transition from conventional to alternative meats production, the impact of the transition on the number of jobs at the conventional meat industry, the foreseen impact on jobs and qualification needed in each one of the stages of the cultivated meat chain, namely: (1) stage one: suppliers of systems, ingredients and services for cultivated meat production; (2) stage two: growing factories working with bioreactors and scaffolds; (3) stage three: processing, distribution and marketing activities. We additionally asked about carriers’ opportunities and the background knowledge that may be needed from professionals to act in each stage of the cultivated meat chain. Since knowledge about specific stages of the production chain of alternative meats may vary among the respondents, due to their specific backgrounds and expertise, related items of the questionnaire were optional, i.e., respondents were allowed to move forward without providing an answer for such questions (e.g., Q7: Cultivated meat activities may promote the creation of new jobs in the country in the first stage of the chain (suppliers of systems and services for cultivated meat production); Open question: Which careers are likely to emerge or strengthen at this stage of the cultivated meat chain (processing/distribution/marketing)?). The questionnaire and additional required documents were submitted to the Ethics Committee for Research with Humans at the Federal University of Paraná (Brazil) and the project was approved under protocol number 38617320.0.0000.0102. The questionnaire used in the study is available as a supplementary document.

Data analysis

Based on the non-parametric characteristic of the data collected, as per Shapiro-Wilk test, we conducted descriptive and comparison analyses amongst groups by location with the Kruskal–Wallis test, which is used to compare values from independent samples (Katz and McSweeney, 1980). The Dunn’s post hoc test, with Bonferroni correction, was used for multiple comparisons between pairs of location groups.

Results

Considering their current country of residence, in order to understand how the experts considered the impact of alternative meat production on jobs at the conventional meat industry, we asked them three questions. A high trend of disagreement was seen concerning the migration of the workforce in the current animal production system. In this case, 77.9% of the experts disagreed or strongly disagreed with the possibility of the migration from jobs linked to animal production to other areas. The detailed statistics of these first set of questions are shown in Table 3.

Regarding the qualifications of the labour force, 64.0% of the participating experts disagreed or strongly disagreed that the people currently working on animal farms, upstream in the conventional animal meat chain, have sufficient qualifications to work in other sectors. When asked about current jobs in the downstream stages of the conventional meat production chain, such as processing, marketing and distribution, 47.1% of the experts agreed or strongly agreed that the people working in these stages of the production chain are sufficiently qualified to work in the corresponding stages of the emerging cultivated meat industry. These results may be related to the fact that people working in the upstream stages are less qualified when formal education is considered. For example, only 18, 22 and 24% of Brazilian workers employed in the beef, pork and chicken chains completed the second level of education (12 years of formal schooling) (CEPEA, 2021). On the other hand, the results can also be linked to the perspective that the disruption in the first stages of the chain will be more intense compared to conventional meat production due to the technological paradigm shift (Gerhardt et al., 2020; Reis et al., 2020a). Instead, the downstream stages of the chain have fewer challenges in terms of technological development, despite incremental innovations and the need to adapt to new products (Morach et al., 2021).

Data on the current skills of animal farmworkers for transitioning to new industries revealed different patterns of response amongst locations, with significant differences between Europe and Brazil; no significant difference was observed between the United States and Europe or Brazil. Although most experts from all regions believe that workers employed in animal production may migrate to other sectors, Brazilian experts disagreed more strongly with this statement compared to European experts. This result may be related to the current low level of education of Brazilian agricultural workers. The national census of the Brazilian agricultural sector (IBGE, 2017) showed that of agricultural producers as a whole, 72% have less than 5 years of formal schooling and 23% reported not being able to read and write.

Concerning the impact of cultivated and plant-based meat on the number of jobs in the conventional meat industry, the experts showed a high tendency of agreement with the claim that the production of alternative meats will have a negative impact on the number of jobs in the conventional meat production chain (Table 4).

Considering the participants’ expectations, 56.2% of them agreed or strongly agreed that the production of cultivated meat will lead to a decrease in the number of jobs in the conventional meat chain. Furthermore, 46.3% of the experts agreed or strongly agreed that plant-based meat production will have a negative impact on the number of jobs in the conventional meat industry, while 33.0% disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. This result may be related to the predictions that cultivated meat innovation is more disruptive compared to other types of alternative protein production, as it significantly changes the production process (Gerhardt et al., 2020; Tomiyama et al., 2020). The plant-based production chain uses a structure that already exists for agriculture, processing and distribution. These findings can also be explained by recent expressive investments in the cultivated and plant-based products segment by large companies traditionally active in the conventional meat production chain (Morach et al., 2021; Mancini and Antonioli, 2022). For example, the US company Tyson Foods invested in Beyond Meat, a well-known plant-based start-up (Santo et al., 2020). This may indicate that the same players will take over some of the activities in alternative meat chains. This form of transition may mitigate the impact on the number of jobs in the conventional chain, as the change may occur in a gradual, substitutive transition of the workforce from the conventional to the cell- and plant-based meat chain.

From another perspective, the data also show that a significant proportion of experts disagreed to some extent with the potential negative impact of new means of production on the number of jobs in the conventional meat chain, 22.1% in relation to cultivated meat and 33.1% in relation to plant-based meat. These results may be related to a complementary transition scenario (Stephens et al., 2018), where production systems do not compete with each other and only add up to meet society’s growing demand for meat (Weis, 2015), or to another scenario where the organisations controlling the conventional means switch their production to the new systems (Reis et al., 2020a).

Expert opinion on the impact of plant-based meat on jobs in the current meat system also led to different response patterns in the United States compared to Brazil. No significant difference was found when comparing Europe to the United States or Brazil. In this sense, Brazilian experts seem to be more sceptical about the negative impact of plant-based meat production on the number of jobs in the conventional meat chain. These results may be explained by the investments of large Brazilian meat processing companies such as BRF and JBS in alternative meat production (Baker, 2021), implying that the process in this country may be driven by the large conventional companies. Thus, noting that the leading companies in the Brazilian conventional meat chain are looking at new technologies, experts may realise that these will have less of a negative impact on the traditional production chain.

Given the forecast that by 2040 only 40% of the consumer market for meat will consist of animal slaughter products (Gerhard et al., 2020), we asked about the expected extent of job losses in animal farms by 2040 (Table 5).

Experts’ expectations of the impact of alternative meat production on animal farm jobs averaged 20.0% in Brazil, 30.7% in Europe and 39.2% in the United States. Furthermore, the answers showed different patterns between the United States and Brazil. No significant difference was found when comparing Europe to the United States or Brazil. This result may be explained by the projection that conventional dairy and meat production in the United States will decline by up to 90% by 2035, which may lead to a collapse of the country’s conventional meat production chain (Tubb and Seba, 2020). The upstream stages of the cultivated meat chain, particularly animal producers and farmers who grow crops, remain a key issue in a substitutive transition process for cultivated meat production (Stephens et al., 2018; Broad, 2020; Mancini and Antonioli, 2022). However, in addition to the opportunities already mentioned in relation to the transition of activities to the alternative meat chain in rural areas, such as ingredient and cell food production (Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021), there is also an opportunity to provide better working conditions for rural workers. Currently, work in slaughterhouses, for example, is based on intensive labour exploitation, with poor working conditions (Marzoque et al., 2021) and high rates and risks of occupational accidents (Takeda et al., 2018). Furthermore, decoupling the animal from meat production may also lead to better mental and emotional conditions for workers currently involved in conventional meat production (Hutz et al., 2013; Baran et al., 2016). In other words: such transition process includes the potential solution of the exploitation of non-human animals and at least partial improvement of the poor conditions of human labour in the conventional animal food production chain.

Furthermore, 34.5% of the experts chose not to answer the question about the expected loss of jobs in the animal farm industry (see Table 5). This result suggests that even for landscape specialists, given the complexity of the transition process (Herrero et al., 2011), the question of the impact on jobs is still open. Some key issues, such as the technical and technological feasibility of large-scale cultivated meat production and the attitude of decision-makers to restrict or facilitate the transition process, are not yet settled and may play a crucial role in this change (Morach et al., 2021).

Experts also commented on the impact of cultivated meat production on the upstream stage of the cultivated meat value chain. 87.5% of our respondents agreed or strongly agreed that cultivated meat activities will create new jobs in their respective countries (Table 6).

In addition, the experts showed a high trend of general agreement of 91.9% that investment in training and development of people is necessary to create employment opportunities.

Although all locations showed a high trend of agreement with these questions, Brazil and Europe showed different patterns of response. No significant difference was found when comparing the United States and Europe or Brazil. Although the opinion of Brazilian experts was significantly more optimistic than that of Europeans regarding the possibility of job creation through the new cultivated meat production chain, the need for training is reversed in the two geographical contexts. The Brazilian experts indicated that more training and human resource development activities are needed than the European experts. This result may be related to the low qualification of Brazilian workers compared to Europeans. In Brazil, 20.1% of adults aged 25–64 have a tertiary degree, compared to 42.3% of Dutch, 42.4% of Belgians, 39.7% of French, 32.9% of Poles, 31.3% of Germans and 20.1% of Italians (OECD, 2022). The difference between education levels may help explain the greater need for training and skills development that Brazilian professionals have compared to Europeans.

In addition, we asked the experts in an open question which professions and fields of knowledge may be strengthened or created at the first stage of the production chain for cultivated meat. In this question, 82.9% of the professions mentioned by the experts refer to activities or training in the technical knowledge area, such as natural sciences, exact sciences and engineering, and 17.1% of the answers referred to activities or training in management areas of social applied sciences and humanities. Table 7 shows the most important occupations mentioned by the experts in descending order of the frequency with which they were mentioned.

The experts predicted that 58.2% of the occupations at this stage of the value chain of cultivated meat production will be based on engineering (25.3%), biology (24.6%), nutrition (8.22%) and their specialties. In addition, 11.0% of the responses indicate that laboratory activities and basic research are most important at this stage of the chain. Furthermore, 17.1% of the experts’ answers pointed to opportunities for management carriers, e.g., marketing, communication, logistics, and production and quality control at this stage of the value chain for cultivated meat. These results may be explained by the idea that food is designed in the same way that software developers design apps, what Tubb and Sena (2020) have called food-as-software. For these authors, the driving force behind this phase is the new possibilities of precision biology, which will seek improved quality, scalability, nutritional value, taste, texture and cost of new products.

Also noteworthy in the results of Table 7 is the fact that only Brazilian experts indicated the field of veterinary and animal sciences as promising professions for the first stage of the new cultivated meat chain (3.42%). In terms of frequency, these occupations were the third most suggested by Brazilian experts. This result may be related to recent initiatives in the country around the topic of cellular animal sciences (Reis et al., 2020a). For example, an event organised by the Federal University of Paraná, the Regional Council of Veterinary Medicine of Paraná and the Brazilian Animal Science Society to discuss the topic in 2021, and a course entitled “Introduction to Cellular Animal Science” offered annually at postgraduate level by the Postgraduate Programme in Veterinary Sciences at the Federal University of Parana since 2020 (Heidemann et al., 2020b). These professions have traditionally been involved in the production of conventional meat and the category may offer resistance to alternative proteins, especially if they feel excluded in the transition to new production systems (Heidemann et al., 2020b). Even if their commitment to alternative systems is not obvious, such professionals can transition and contribute to the development of the new industry with their knowledge of the conventional meat chain and its specificities, such as animal health, genetics, nutrition, meat inspection and meat quality; the veterinarians and animal scientists may also play a critical role in reducing resistance and supporting animal farmers in their transition process. Finally, veterinarians are in the best position to understand the power of alternative meats to prevent animal disease and other forms of animal suffering.

In terms of the expertise and background required to work in the first stage of the cultivated meat production chain, the experts indicated that 69.4% of the expertise will come from biology (cell biology, genetics), engineering (tissue and cell specialities), production (scaling, production processes and food industry) and food science (nutrition, food sense, taste and mimicry, food analysis). In addition, 19.0% of the required skills are likely to be related to management skills, such as supply chain management, start-up management, marketing and consumer relations. These results may be related to the current development process of the cultivated meat production model (Stephens et al., 2018; Bryant, 2020; Moritz et al., 2022), where technological challenges are at the forefront to bring it to life (Morach et al., 2021). The detailed results are presented in Table 8.

We also asked the experts for their opinion on the possibilities of cultivated meat production in its second phase, especially on the activities in growing factories. The experts tended to agree with the idea of new employment opportunities in the second stage of the cultivated meat production chain. Most experts (91.4%) agreed or strongly agreed with the assertion that cultivated meat activities in their respective countries will create new jobs in the second stage of the value chain. The results are shown in Table 9.

In addition, 92.9% of experts agreed or strongly agreed that investment in training and development of people will be necessary to create new employment opportunities during this phase.

Although professionals in all regions give a positive assessment of new employment opportunities and skills needs, the responses from Brazil and Europe showed different patterns. The results suggest that Brazilian experts are more optimistic about the opportunities in this second stage of the production chain than European respondents. No significant difference was found when comparing the United States with Europe or Brazil.

Experts predict that 64.4% of career opportunities on the second stage of the cultivated meat chain will be in technical fields such as engineering, biology, food science and their specialties (see Table 10). In 11.1% of the responses, the experts also indicated that careers in basic research and laboratory activities will be most in demand. A smaller group of responses, 8.89%, referred to opportunities in management jobs, such as production management, communications and marketing.

It was also suggested that 55.9% of the expertise needed in this second phase is in the fields of biology, food science and engineering, most of which is related to the cultivation and structuring of cells and tissues. Besides, 23.4% of respondents indicated that knowledge of production processes (9.0%), food safety (8.1%) and technical knowledge of specific equipment for growing and patterning cells and tissues (5.4%) will also be in high demand (see Table 11 for detailed data).

Cultivated meat production is considered the most consequential disruption in food production since the first domestication of plants and animals 10,000 years ago (Herrero et al., 2011; van Hout, 2020). Our results showed that the need for new knowledge may arise in the interdisciplinary interaction of biology, engineering and food science. In this sense, Tubb and Seba (2020) claimed that one of the main drivers for the upheaval of food production is knowledge from synthetic biology, which is interested in the production of new ingredients and innovations in the production systems themselves; they also claimed that synthetic biology is undergoing a conceptual transformation, becoming an engineering discipline that brings together knowledge from genetic engineering, systems biology, metabolic engineering and computational biology.

Finally, we have also examined how the experts assessed the possibilities for job creation in the third stage of the cultivated meat production chain. The third stage consists of the downstream activities in the production chain, such as processing, distribution, and interaction with the consumer market. The expert opinion showed a trend of agreement (83.9%) on the claim that new jobs are created at the downstream level of the cultivated meat production chain (Table 12). This result may be related to the value chain strategies proposed by Reis et al. (2020b), where the technological challenges of cultivated meat production will be concentrated on the upstream actors, who mainly focus on developing economic and environmental efficiency. In contrast, downstream actors may be more sensitive to market and stakeholder pressures and therefore likely to focus on branding strategies and governance strategies beyond compliance (Reis et al., 2020a, 2020b).

The results in Table 12 show a statistically significant difference between Brazil and Europe and between the United States and Europe. In this sense, Brazilian and American respondents were more positive about the possibilities of creating new jobs in the third stage of the cultivated meat production chain compared to European respondents. There was no statistically significant difference when comparing the results between Brazil and the United States.

In the third stage of the cultivated meat chain, occupations in management were more frequently mentioned as the most important (52.2%, Table 13). In particular, experts indicated that occupations related to supply management, production management, communication and interaction with consumers, and process and quality management are most in demand at this stage of the chain. In addition, in a second group, occupations related to food science and its sub-areas are perceived as potentially promising careers. At this stage, occupations based on knowledge in engineering (9.8%) and biology (7.6%) were less frequently indicated.

Compared to the previous stages of the production process, there is a clear change, as more technical occupations were named in the first and second stages and more management occupations in the third stage. These results reflect the actual level of development of the cultivated meat industry, where the main challenges are focused on the technical issues of production and scalability of cultivated meat, both upstream stages (Bhat et al., 2019; Santo et al., 2020). In the third stage, processing, distribution and marketing can be carried out by the same companies that operate in the conventional animal meat production chain at this stage. Examples include recent investments by major players in the conventional meat industry, such as Tyson, JBS and BRF, in the cultivated meat and plant-based meat segments, either through direct investments or through investments in investment funds (Baker, 2021).

We also asked the experts what background knowledge and expertise will be most valued in the third stage of the cultivated meat chain. The experts surveyed indicated that management skills and knowledge will be most important (38.6%), followed by knowledge of food science (17.1%) and also knowledge of product safety, quality and certifications (11.4%) (Table 14).

These findings echo the claims by Tubb and Seba (2020) that the elimination of the cow in meat production will trigger change throughout the supply chain. Companies operating in the conventional production segment currently benefit from inventiveness and bureaucratic productive and organisational structures and processes that favour incremental thinking over disruptive thinking. So, in addition to the expected changes in the consumer market (Gerhardt et al., 2020), companies will also have to demonstrate their potential to adapt, while also challenging the management mechanisms themselves.

Discussion

First, our results suggest that the transition of the meat production system has an impact on jobs in the first stage of conventional production, especially on animal farmers. The perceived difficulty of people currently working in livestock production to move into other areas of the new alt-protein systems may be related to the disruptive nature of these innovations (Gerhardt et al., 2020; Rischer et al., 2020; Reis et al., 2021), where the skills and abilities required to work in an industry become obsolete with the advent of novel materials and production processes (Perez, 2010; Nagy et al., 2016). These findings are also linked to studies highlighting that the greatest pressure on the conventional meat chain in the face of food production transition will be on animal farmers, crop-growing farmers, and the rural community at large (Chriki and Hocquette, 2020; Tubb and Sena, 2020; Helliwell and Burton, 2021), who may suffer income losses and job losses as a result of the transition to more urban meat production (Rubio et al., 2020; Moritz et al., 2022).

In contrast, other studies (e.g., Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021; Morais-da-Silva et al., 2022; Moritz et al., 2022) highlight the various opportunities that arise for rural producers in the face of changes in the food production, such as the cultivation of ingredients for crop production and cultivated meat as a source material that provides genetic and cellular material for the production of cultivated meat. Although the impact on the conventional sector is still open due to the early stage of the production system, experts have indicated that pressure on animal producers may be expected in the different contexts studied. Our findings therefore suggest that the issue of farmers needs to be analysed as an integral part of the transition itself and therefore addressed through public policies and incentives to upskill the labour force in these different contexts.

Second, in terms of jobs created at different stages of the chain, our study shows that experts expected an opportunity for new and better jobs at different stages of the alternative protein production chain. These results support the findings of other studies where stakeholders and experts indicated that cultivated meat will create new employment opportunities in addition to improving food security and human health benefits (Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021; Moritz et al., 2022), as well as strong direct and indirect benefits for animals (Heidemann et al., 2020a).

Regarding jobs in the first production stage in the new chain, despite the risk that rural producers will be excluded from the meat production process due to a process of urbanisation of meat production by alternative means (Tubb and Seba, 2020; Chriki and Hocquette, 2020), there is an opportunity to further educate this workforce, which in the past was one of the most difficult and dangerous jobs, including low wages, exploitation and high risks (Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021).

In their study of the impact of cultivated meat and plant-based meat in rural areas of agricultural production and among animal farmers in the United States, Helliwell and Burton (2021) pointed out that the potential threats of this change are the loss of livelihoods for farmers and grain producers for animal feed, the presence of barriers to the inclusion of these rural producers in the emerging alternative protein sectors, and the possibility of exclusion of these sectors.

However, in a scenario where these farmers are involved in the production process of alternative proteins, new business opportunities may arise for them, such as the supply of ingredients for the plant-based industry and raw materials for cultivated meat media, as well as other higher value activities, e.g. specialising in the supply of cells and genetic material for cultivated meat, new market opportunities, such as mixed products—part plant-based, part cultivated meat—in addition to the opportunity to operate in a market niche with new regenerative values and animal welfare (Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021). In this case, universities, NGOs and governments have an important role to play in providing skills and training opportunities for farmers and in supporting the transition to different activities related to agriculture in this new chain (Kurrer and Lawrie, 2018; Mancini and Antonioli, 2022). Another point concerns the possibility that the production of cultivated, and plant-based meat may create opportunities for the transition of the labour system itself, where farmers’ relationships with actors downstream in the production chain can be more balanced and fairer compared to the reality of the conventional meat production chain (Kano et al., 2020; Bryant and Van der Weele, 2021; Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021).

The third point to highlight as a contribution of this study is the survey of the expertise that will be required along the new production chain. Our findings support the expectation that new jobs will be created and workers with different skills and background knowledge will enter the meat production chain, such as chemists, engineers, biologists and food scientists (Tubb and Seba, 2020; Reis et al., 2020a; Mancini and Antonioli, 2022).

A fourth point: Our study showed that Brazilian experts have more positive expectations compared to European experts. This difference may be due to cultural aspects, for example, Brazilians tend to be more concerned about animal welfare than other nationalities (Anderson et al., 2020), and studies have shown that cultivated meat products have a high acceptance potential among consumers in the country (Valente et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2021b). Additionally, another a few possible reasons may be given for the more optimistic view of the Brazilian experts compared to the Europeans. The first is the recent news that major Brazilian meat processors such as BRF and JBS are planning to produce cultivated meat in Brazil, which may help create jobs in this intermediate stage of the production chain. Brazil also has a recognised tradition in the production of food of animal origin. The country ranks second among the largest beef producers, third in chicken production and fifth in pork production (FAO, 2022). The opportunity to create new food production chains may therefore directly mean the creation of new jobs in the country.

In terms of social impacts on jobs, despite the many skills and employment opportunities highlighted at different stages of the production chain, there may be unintended consequences if, within countries, jobs are primarily created in urban rather than rural areas (Bryant, 2020; Treich, 2021), or even a reality in which the employment and income conditions of the chain are even more concentrated in high-income countries than in low-income countries (Hocquette, 2016; Godfray et al., 2019). In other words, even if the new production chains require more skilled labour and offer better working conditions (Godfray et al., 2019), inequalities between regions and countries need to be addressed through equalising public policies, balanced global value chains and more integrated business models (van der Weele et al., 2019; Reis et al., 2020a; Abrell, 2021).

The evolution of the meat production system transition is thus likely to depend on public policies and regulations that support technological development, encourage the creation of businesses in the new production chain, and seriously address the consequences of the transition process itself, such as the possible replacement of animal farmers’ activities (Morach et al., 2021; Newton, and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021). On the other hand, the established power relations and bureaucratic systems of the conventional meat system may delay the progress of the transition, as many regulators and decision-makers tend to follow the agricultural lobby (Moritz et al., 2022).

Finally, it is important to stress that the transition to more modern food production systems is a comprehensive process that goes beyond the production of alternative meats. The literature highlights that agriculture is in its fourth revolution (Rose and Chilvers, 2018) or in a phase referred to as smart farming (Blok and Gremmen, 2018; Boursianis et al., 2022). Examples of current innovations in agriculture include the use of artificial intelligence in decision-making (López and Corrales, 2018) and robots in various activities previously developed only by humans (Sparrow and Howard, 2021). These changes and the possible transition to the production of alternative meat may be seen as elements of a sociotechnical transition in agriculture. Sociotechnical transition theory states that when a more efficient technological proposal is discovered, there is support from the landscape environment and actors are interested in developing and consuming the new technology, opportunities open up to integrate niche initiatives into the regime level (Geels, 2020; Schot and Geels, 2007). Thus, in the case of a transition to alternative meats, general opportunities and challenges may arise, as for instance in the case of employment. The fostering of comprehensive benefits for all depends on society and its representatives, in using available knowledge to secure the best management of the transition to alternative meats.

Contributions, limitations and future research

Contributions to the literature

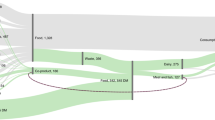

Our results contribute to the findings of other studies (e.g. Tubb and Seba, 2020; Helliwell and Burton, 2021; Newton, and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021; Treich, 2021) that have shown that the transition of the meat production system may put pressure on animal farmers and, depending on the level of engagement with the alternative meat production system (Morais-da-Silva et al., 2022), be associated with undesirable consequences such as loss of income, unemployment, loss of rural activities and bankruptcies in the first stage of the production chain. On the other hand, when considering the employment in the traditional meat value chain, only a small proportion of jobs are in upstream stages such as animal farming (7.9%) and crop production (23.2%), while most jobs in this chain are in downstream stages such as processing (19.3%) and distribution (57.5%) (Tubb and Seba, 2020). Complementarily, our data show that plant-based and cultivated meat have the potential to create new and high-skilled jobs, which in turn may generate new activities for rural producers, better working conditions compared to those in the conventional system, new specialities and higher-income jobs, and more balanced and fairer relationships among actors throughout the value chain. Additional literature has also pointed out such social opportunities (Newton and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021; Mancini, and Antonioli, 2022). Although these findings appear controversial, they reinforce the need for public policies and governance systems to drive the on-going meat system change (Abrell, 2021; Christiaensen et al., 2021; Morris et al., 2021) and avoid unintended consequences (Mattick et al., 2015; Herrero et al., 2011).

As a novel contribution that extends the debate on the possible social impact of alternative meats, we have discussed the impact on jobs and shown that technical occupations and expertise will be in demand mainly in the first and second stages of the chain, while management occupations and background knowledge will be needed in the third stage. As for technical professions, complementing the idea of Food as Software (Tubb and Seba, 2020), we have demonstrated the potential for interdisciplinary collaboration amongst the fields of biology, veterinary, animal science, a variety of engineering backgrounds and food science to drive technological development in this area. In all stages of the value chain, a diversity of knowledge and expertise was indicated by the interviewed experts, suggesting that solutions and developments may be better addressed by combining different areas of knowledge.

Finally, our study presents unprecedented comparative data from three different regions, providing a comprehensive view of meat system change beyond the reality of a single country, which encompasses different cultures and socioeconomic realities from regions that are highly relevant in the context of both meat production and consumption. This demand for comparative analyses that consider the singularities of geographical areas aims to cover a research gap in the literature (Abrell, 2021; Newton, and Blaustein-Rejto, 2021; Moritz et al., 2022).

Practical contributions and policy implications

As the transformation of meat production systems is in an initial transition process among animal farmers, there is still room for producers to participate and adapt their core activities to the new meat production systems. The results suggest that it is important to pay attention to the skills of animal farmworkers so that they are not left out of the process. Policymakers will be faced with the challenge of creating public policies that focus less on mass unemployment compensation and more on supporting, training and upskilling workers in the conventional meat system so that they make the transition to the new industry and are trained for new roles and activities.

In terms of the professions that are created or strengthened in the cultivated meat production chain, the results show a variety of background knowledge and expertise needed throughout the cultivated meat value chain. In the upstream stages of the chain, experts pointed to the potential for technical professions such as engineering, food science and biology and their multiple specialisations. Skills in cell manipulation and propagation, tissue formation and food structuring were cited as the most important in the early stages of the production chain. These findings can be linked to the need for interdisciplinary knowledge to support the technological development of disruptive innovation of cultivated meat and cellular agriculture in general. In the downstream phases of the chain, on the other hand, experts believe that management skills are more in demand. As these are phases where proximity to the consumer is present, the challenges will be to attract these consumers to the new products. These results open up the possibility for universities and research institutes to develop new courses of study or specialisations based on the interdisciplinary interaction of knowledge, focusing on post-animal food production.

The research also supports an understanding of the potential of alternative meat production systems to create new jobs. Because of the higher skills associated with and required of the new production methods, there is the potential to create jobs that are physically, emotionally and economically safer for workers. In this sense, the study shows that different actors such as universities, research institutes, regulators, non-governmental organisations and governments need to be involved in order to create a governance system that drives the transition beyond animal-based food systems. Therefore, such actors need to develop compensatory and incentive measures so that differences and inequalities amongst countries and locations are not exacerbated. In terms of public policy, the gradual transition of financial and fiscal incentives from the conventional meat sector to the alternative meat sector can also accelerate the required technological development and thus speed up the transition to new forms of food production.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

As a first limitation, the experts’ opinions reflect their perceptions from the current reality of the transformation of the meat production system. In the case of cultivated meat production, for example, although it is a desirable near future (van der Weele et al., 2019), several issues such as the technical feasibility of large-scale production, product affordability, consumer acceptance, and broader issues such as institutional change, business models, relationships among organisations, decision-makers’ attitudes and incentives towards the new systems complicate predictability. Recent research has linked the potential for technological disruption in jobs to the elasticity of demand for novel products (Piva and Vivarelli, 2018; Bessen, 2019). In this sense, studies looking at a broader relationship amongst consumption, innovation and employment may provide complementary insights to our findings.

Second, our study has attempted to capture a variety of impacts of the new production systems along the different stages of the production chain. Although the results provide an original and informative overview of changes throughout the value chain, qualitatively oriented studies at each stage can enrich and deepen the discussion. In particular, we emphasise the importance of studying the impact for animal farmers, as they are the group that will potentially be under the greatest pressure in the transition of the food system.

Although we have reached a qualified sample of experts who support our findings, a broader representation may allow for better comparability among countries. Studies in other locations, especially in regions with different labour force circumstances, such as low-income countries with predominantly rural populations, may provide complementary conclusions.

Conclusion

Based on the experts’ forecasts, the results of this study show the potential of plant-based and cultivated meat production for the creation of new and high-skilled jobs. The data analysis showed that the impact of novel food production systems on jobs in conventional meat production is perceived differently at different stages of the value chain. In particular, the results showed a pressure point on animal farmers, who may be most affected in a scenario of a fast transition. In the downstream stages of the production chain, the experts predict the creation of new jobs. In addition, the transition is likely to have less potential to threaten downstream jobs in the conventional meat chain, which are the stages the employ the highest number of people. Comparing countries, the results show greater optimism among Brazilian experts about the potential of plant-based and cultivated meat production to create jobs; European respondents were the least optimistic about the possibility of the new meat production systems creating new jobs. Although such differences seem consistent in our study, further cross-national studies are needed. Overall, our study presents the opportunities and challenges of novel alternative meat systems with new data and insights for the development of policies, actions and strategies, which may support job creation and improvement in skills and income as the new post-animal bioeconomy unfolds, bringing along major benefits in terms of environment, animal ethics, human health and food security.

Data availability

Data underpinning the study are included in the supplementary files.

References

Abrell EL (2021) From livestock to cell-stock: Farmed animal obsolescence and the politics of resemblance. TSANTSA–J Swiss Anthropol Assoc 26:37–50

Anderson J, Tyler L (2020) Attitudes toward farmed animals in the BRIC countries. Available online: https://faunalytics.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/BRIC-Full-Report.pdf

Baker A (2021, November 2). The cow that could feed the planet. Time. https://time.com/6109450/sustainable-lab-grown-mosa-meat/

Baran BE, Rogelberg SG, Clausen T (2016) Routinized killing of animals: going beyond dirty work and prestige to understand the well-being of slaughterhouse workers. Organization 23(3):351–369

Bessen J (2019) Automation and jobs: When technology boosts employment. Econ Policy 34(100):589–626

Bhat ZF, Morton JD, Mason SL, Bekhit AEA, Bhat HF(2019) Technological, regulatory, and ethical aspects of in vitro meat: a future slaughter-free harvest. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 18(4):1192–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12473

Blok V, Gremmen B (2018) Agricultural technologies as living machines: Toward a biomimetic conceptualization of smart farming technologies. Ethics Policy Environ 21(2):246–263

Bogner A, Menz W (2009) The theory-generating expert interview: epistemological interest, forms of knowledge, interaction. In: Bogner A, Littig B, Menz W (eds.) Interviewing experts. Palgrave Macmillan, UK, pp. 43–80

Broad GM (2020) Making meat, better: the metaphors of plant-based and cell-based meat innovation. Environ Commun 14(7):919–932

Bryant CJ (2020) Culture, meat, and cultured meat. Journal of Animal Science 98(8). https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skaa172

Bryant CJ, van der Weele C (2021) The farmers’ dilemma: meat, means, and morality. Appetite 167:105605

Boursianis AD, Papadopoulou MS, Diamantoulakis P, Liopa-Tsakalidi A, Barouchas P, Salahas G, Karagiannidis G, Wan S, Goudos SK (2022) Internet of things (IoT) and agricultural unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in smart farming: a comprehensive review. Internet of Things J (Netherlands). 18: 100187

Cameron BC, O’Neill S (2019). State of the industry report: plant-based meat, eggs, and dairy. The Good Food Institute

Carolan M (2020) Automated agrifood futures: robotics, labor and the distributive politics of digital agriculture. J Peasant Stud 47(1):184–207

CEPEA (2021) Retrospectiva de 2020. https://www.cepea.esalq.usp.br/br/releases/cepea-retrospectivas-de-2020.aspx

Chriki S, Hocquette JF (2020) The myth of cultured meat: a review. Front Nutr 7:7

Christiaensen L, Rutledge Z, Taylor JE (2021) The future of work in agri-food. Food Policy 99:101963

Conteratto C, Artuzo FD, Benedetti Santos OI, Talamini E (2021) Biorefinery: a comprehensive concept for the sociotechnical transition toward bioeconomy. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 151:111527

Eisen MB, Brown PO (2022) Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO2 emissions this century. PLOS Climate, 1(2) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000010.

FAO (2022) Crops and livestock products. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL

Fernandes AM, Teixeira ODS, Revillion JP, Souza ÂRLD (2021a) Panorama and ambiguities of cultured meat: an integrative approach. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 62:5413–5423

Fernandes AM, Costa LT, Teixeira ODS, F. V, Revillion JPP, Souza ÂRLD (2021b) Consumption behavior and purchase intention of cultured meat in the capital of the “state of barbecue,” Brazil. Br Food J 123(9):3032–3055

Frey BB (2018) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506326139.

Geels FW (2020) Micro-foundations of the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions: Developing a multi-dimensional model of agency through crossovers between social constructivism, evolutionary economics and neo-institutional theory. Technol Forecast Social Change 152:119894

Gerhardt C, Suhlmann G, Ziemßen F, Donnan D, Warschun M, Kühnle HJ (2020) How will cultured meat and meat alternatives disrupt the agricultural and food industry? Ind Biotechnol 16(5):262–270

Godfray HCJ et al. (2019, January). Meat: the future series—alternative proteins. Report. World Economic Forum. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/170474/

Haleem A, Mannan B, Luthra S, Kumar S, Khurana S (2019) Technology forecasting (TF) and technology assessment (TA) methodologies: a conceptual review. Benchmarking 26(1):48–72

Heidemann MS, Molento CFM, Reis GG, Phillips CJC (2020a) Uncoupling meat from animal slaughter and its impacts on human-animal relationships. Front Psychol 11:1824

Heidemann MS, Taconeli CA, Reis GG, Parisi G, Molento CF (2020b) Critical perspective of animal production specialists on cell-based meat in Brazil: from bottleneck to best scenarios. Animals 10(9):1678

Helliwell R, Burton RJ (2021) The promised land? Exploring the future visions and narrative silences of cellular agriculture in news and industry media. J Rural Stud 84:180–191

Herrero M, Gerber P, Vellinga T, Garnett T, Leip A, Opio C, Westhoek HJ, Thornton PK, Olesen J, Hutchings N, Montgomery H, Soussana JF, Steinfeld H, McAllister TA (2011) Livestock and greenhouse gas emissions: the importance of getting the numbers right. Anim Feed Sci Technol 166–167:779–782

Hirt LF, Schell G, Sahakian M, Trutnevyte E (2020) A review of linking models and socio-technical transitions theories for energy and climate solutions. Environ Innov Soc Trans 35:162–179

Hocquette JF (2016) Is in vitro meat the solution for the future? Meat Sci 120:167–176

Hutz CS, Zanon C, Neto HB (2013) Adverse working conditions and mental illness in poultry slaughterhouses in southern Brazil. Psicol Reflex Crit 26(2):296–304

IBGE (2017) Censo agropecuário. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/3096/agro_2017_resultados_definitivos.pdf

IPCC (2020) Climate change and land. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2020/02/SPM_Updated-Jan20.pdf

Johnstone P, Rogge KS, Kivimaa P, Fratini CF, Primmer E, Stirling A (2020) Waves of disruption in clean energy transitions: sociotechnical dimensions of system disruption in Germany and the United Kingdom. Energy Res Soc Sci 59:1–13

Kano L, Tsang EWK, Yeung H, Chung W (2020) Global value chains: a review of the multi-disciplinary literature. J Int Bus Stud 51(4):577–622

Katz BM, McSweeney M (1980) A multivariate Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc procedures. Multivar Behav Res 15(3):281–297

Kurrer C, Lawrie C (2018) What if All Our Meat Were Grown in a Lab? https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2018/614538/EPRS_ATA(2018)614538_EN.pdf

López ID, Corrales JC (2018) A smart farming approach in automatic detection of favorable conditions for planting and crop production in the upper basin of Cauca River. Adv Intell Syst Comput 687:223–233

Mancini MC, Antonioli F (2022) The future of cultured meat between sustainability expectations and socio-economic challenges. In: Bhat R (ed.) Future foods: global trends, opportunities and sustainability challenges. Academic Press, pp. 331–350

Marzoque HJ, Cunha RF, da, Lima CMG, Nogueira RL, Machado VE, de A, De Alencar Nääs I (2021) Work Safety in slaughterhouses: general aspects. Res Soc Dev 10(1):e55310111980. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i1.11980

Mattick CS, Landis AE, Allenby BR (2015) A case for systemic environmental analysis of cultured meat. J Integr Agric 14(2):249–254

Morais-da-Silva RL, Reis GG, Sanctorum H, Molento CFM (2022) The social impact of the transition from conventional to cultivated and plant-based meats: evidence from Brazil. Food Policy. 111:102337

Morach B, Witte B, Walker D, von Koeller E, Grosse-Holz F, Rogg J, Schulze U (2021) Food for Thought: The Protein Transformation. Ind Biotechnol 17(3):125–133

Moritz J, Tuomisto HL, Ryynänen T (2022) The transformative innovation potential of cellular agriculture: Political and policy stakeholders’ perceptions of cultured meat in Germany. J Rural Stud 89:54–65

Morris C, Kaljonen M, Aavik K, Balázs B, Cole M, Coles B, White R (2021) Priorities for social science and humanities research on the challenges of moving beyond animal-based food systems. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–12

Mouat MJ, Prince R (2018) Cultured meat and cowless milk: on making markets for animal-free food. J Cult Econ 11(4):315–329

Nagy D, Schuessler J, Dubinsky A (2016) Defining and identifying disruptive innovations. Ind Mark Manag 57:119–126

Newton P, Blaustein-Rejto D (2021) Social and economic opportunities and challenges of plant-based and cultured meat for rural producers in the US. Front Sustain Food Syst 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.624270

Nobre FS (2022) Cultured meat and the sustainable development goals. Trend Food Sci Technol 124:140–153

OECD (2022). Adult education level. https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/adult-education-level.htm#indicator-chart

Onwezen MC, Bouwman EP, Reinders MJ, Dagevos H (2021) A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite, 159:105058

Perez C (2010) Technological revolutions and techno-economic paradigms. Camb J Econ 34(1):185–202

Piva M, Vivarelli M (2018) Is innovation destroying jobs? Firm-level evidence from the EU. Sustainability 10(4):1279

Post MJ, Levenberg S, Kaplan DL, Genovese N, Fu J, Bryant CJ, Negowetti N, Verzijden K, Moutsatsou P (2020) Scientific, sustainability and regulatory challenges of cultured meat. Nat Food 1(7):403–415

Reis GG, Heidemann MS, Borini FM, Molento CFM (2020a) Livestock value chain in transition: Cultivated (cell-based) meat and the need for breakthrough capabilities. Technol Soc 62:101286

Reis GG, Heidemann MS, Matos KHOD, Molento CFM (2020b) Cell-based meat and firms’ environmental strategies: new rationales as per available literature. Sustainability 12(22):9418

Reis GG, Heidemann MS, Goes HAA, Molento CFM (2021) Can radical innovation mitigate environmental and animal welfare misconduct in global value chains? The case of cell-based tuna. Technol Forecast Soc Change 169:120845

Rischer H, Szilvay GR, Oksman-Caldentey KM (2020) Cellular agriculture—industrial biotechnology for food and materials. Curr Opin Biotechnol 61:128–134

Rose DC, Chilvers J (2018) Agriculture 4.0: broadening responsible innovation in an era of smart farming. Front Sustain Food Syst, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2018.00087

Rubio NR, Xiang N, Kaplan DL (2020) Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production. Nat Commun 11(1):6276

Santo RE, Kim BF, Goldman SE, Dutkiewicz J, Biehl EMB, Bloem MW, Neff RA, Nachman KE (2020) Considering plant-based meat substitutes and cell-based meats: a public health and food systems perspective. Front Sustain Food Syst 4:134

Schot J, Geels FW (2007) Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy 36(3):399–417

Soriano VS, Phillips CJC, Taconeli CA, Fragoso AAH, Molento CFM (2021) Mind the gap: animal protection law and opinion of sheep farmers and lay citizens regarding animal maltreatment in sheep farming in Southern Brazil. Animals 11:1903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11071903

Sorrell S (2018) Explaining sociotechnical transitions: a critical realist perspective. Res Policy 47(7):1267–1282

Sparrow R, Howard M (2021) Robots in agriculture: prospects, impacts, ethics, and policy. Precis Agric 22(3):818–833

Stephens N, di Silvio L, Dunsford I, Ellis M, Glencross A, Sexton A (2018) Bringing cultured meat to market: technical, socio-political, and regulatory challenges in cellular agriculture. Trend Food Sci Technol 78:155–166

Takeda F, Moro ARP, Machado L, Zanella AL (2018) Indicators of work accidents in slaughter refrigerators and broiler processing. Rev Bras Cienc Avic 20(2):297–304

Treich N (2021) Cultured meat: promises and challenges. Environ Resour Econ 79(1):33–61

Tubb C, Seba T (2020) Rethinking Food and Agriculture 2020-2030: the second domestication of plants and animals, the disruption of the cow, and the collapse of industrial livestock farming. Ind Biotechnol 17(2):57–72

Tuomisto HL, Teixeira De Mattos MJ (2011) Environmental impacts of cultured meat production. Environ Sci Technol 45(14):6117–6123

Tomiyama AJ, Kawecki NS, Rosenfeld DL, Jay JA, Rajagopal D, Rowat AC(2020) Bridging the gap between the science of cultured meat and public perceptions Trends Food Sci Technol 104:144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.07.019

Valente JDPS, Fiedler RA, Sucha Heidemann M, Molento CFM (2019) First glimpse on attitudes of highly educated consumers towards cell-based meat and related issues in Brazil. PLoS ONE 14(8):e0221129

van der Weele C, Feindt P, van der Goot AJ, van Mierlo B, van Boekel M (2019) Meat alternatives: an integrative comparison. Trend Food Sci Technol 88:505–512

van Hout B (2020) Cultured meat and its disruptive potential for the Dutch meat industry: how to deal with effects of disruption? (Doctoral dissertation). University of Groningen

Weis T (2015) Meatification and the madness of the doubling narrative. Can Food Stud 2(2):296–303

Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, Murray CJ (2019) Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393(10170):447–492

Acknowledgements

This research received funding from Global Action in the Interest of Animals—GAIA (Belgium).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This research was funded by GAIA - Global Action in the Interest of Animals (Belgium) and the author H.S. had a consultant position at GAIA during the execution of the study. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection and interpretation of data, or in the writing and revision of the manuscript. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Paraná (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa com Seres Humanos da Universidade Federal do Paraná)—CEP/UFPR, under protocol number 38617320.0.0000.0102.

Informed consent

All participants received and accepted an informed consent statement that explained details of the investigation, including information about the researchers and their affiliation institutions, objectives, potential risks, the voluntary aspect of participation, and the use of data in research and scientific publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morais-da-Silva, R.L., Villar, E.G., Reis, G.G. et al. The expected impact of cultivated and plant-based meats on jobs: the views of experts from Brazil, the United States and Europe. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 297 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01316-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01316-z