Abstract

One of the open issues concerning iron-based superconductors is whether the s± wave model is able to account for the overall effects of impurity scattering, including the low rate of decrease of the critical temperature with the impurity concentration. Here we investigate Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 crystals where disorder is introduced by Au-ion irradiation. Critical temperature, T c , and London penetration depth, λ L , were measured by a microwave resonator technique, for different values of the irradiation fluence. We compared experimental data with calculations made on the basis of the three-band Eliashberg equations, suitably accounting for the impurity scattering. We show that this approach is able to explain in a consistent way the effects of disorder both on T c and on λ L (T), within the s± wave model. In particular, a change of curvature in the low-temperature λ L (T) curves for the most irradiated crystals is fairly well reproduced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The s± phase1,2, an extended s-wave pairing with a sign reversal of the order parameter between different Fermi surface sheets, is the leading candidate for describing the pairing state in most of the iron based superconductors (IBS), including the BaFe2As2 family. According to this approach, superconductivity in these compounds is unconventional and mediated by antiferromagnetic spin fluctuations. However, a general consensus has not been achieved yet, also because of a number of experiments on the effects of non-magnetic impurities that apparently do not fit the s± scenario. In particular, several substitution and particle-irradiation studies reported a much weaker rate of suppression of the critical temperature as a function of the scattering rate than initially suggested for a sign-changing order parameter3,4. Moreover, other unconventional mechanisms have been put forth for describing IBS, e.g. the orbital fluctuations, which favors the s++ state without sign reversal5. A disorder-induced change from sign-reversed (s±) to sign-preserved (s++) symmetry in multi-band superconductors has been predicted6,7 and observed8. Finally, nodal-like behaviors at increasing disorder was observed, e.g. in highly substituted crystals9. Nevertheless, these evidences are not necessarily against the s± picture in disordered samples. As a matter of fact, numerous unexpected novel superconducting properties, including non-trivial impurity effects – that can be even mistaken as evidence for a nodal gap state – can be explained within the s± wave model. This was demonstrated by two-gap analyses10,11, but should be quantitatively confirmed by a comparison of experimental results to more complete models, capturing the rich and complex physics of the material. In fact, there is evidence that at least three bands are required to satisfactorily describe the physical properties of BaFeAs-based compounds12.

In this work, we study the effects of disorder on Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 crystals, with the aim to determine if a discrepancy exists between the disorder-induced suppression of T c and the modifications of the London penetration depth (λ L ) on one hand, and the theoretical expectation for the s± phase on the other hand. Indeed, the analysis of λ L (T) and its modifications as a function of the rate of scattering by impurities has been used to shed light on the order parameter symmetry, the presence of nodes, and whether they are accidental or symmetry-imposed. A standard scheme proposed in literature is the following13: in the case of a superconductor with line nodes, impurity scattering is expected to change the linear temperature dependence of the penetration depth at \(T\ll {T}_{c}\) to become quadratic. On the other hand, intraband scattering would lift the c-axis line nodes in the case of an extended s-wave and induce a change from T 2 to an exponential behavior14. On the contrary, if the starting system is a fully-gapped superconductor, introducing pair-breaking scattering would result in a change from exponential to T 2 variation, and to lower power in the presence of accidental nodes11.

We tested this scheme with samples where disorder was introduced by 250-MeV Au-ion irradiation. Particle irradiation is the way to induce defects without contributing extra chage or huge structural distorsions, contrary to most cases of chemical substitutions. Several experiments have been performed with iron-based superconductors in the last years10,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, but due to the large variety of used particles and compounds, a clear picture has not been reached yet, and a systematic study is still lacking. TEM microscopy revealed that 200-MeV Au-ion irradiation of Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 crystals results in the formation of defects that are linearly correlated along the ion track but – contrary to the case of high-T c cuprates – due to the metallic nature of the compound, they are discontinuous (30–240 nm in length)27. In fact, magneto-optical imaging showed the clear signature of anisotropic flux pinning by discontinuous tracks in crystals irradiated with Au ions at the higher energy of 2 GeV20, which are present also with irradiation at lower energies (250 MeV)29. Moreover, a significant difference with respect to cuprates emerged from a STM analysis of irradiated Fe(Se,Te) crystals, showing that columnar defects produced by 250-MeV Au-ions have a metallic core28, instead of the insulating core of the amorphous tracks that the same ions with the same energy produce in cuprates30. In addition, significant defects other than correlated tracks are produced, such as smaller and more distributed cascades, beside the effects of secondary electrons and strain.

In fact, our data on heavy-ion irradiated Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 crystals do not seem to fit any case of the simplified λ L (T) scheme described above. Thus, a more general theoretical approach is needed to describe the experimental results. Two main aspects in this regard are to be considered: the multi-band nature of the system and the effect of disorder. On one hand, Eliashberg’s theory is the optimal model to describe these systems. Within this approach and especially when the number of bands is higher than two, disorder can be conveniently treated within the Born approximation31, otherwise the T-matrix calculation would increase the number of parameters, making the comparison with experimental data more questionable and possibly not conclusive. Within the Born approximation, the model is sensitive to the global effect of disorder rather than to the details of defects. As a matter of fact, a more general theory to study the role of defects in superconductors was developed32,33,34, but in the proposed formulation only applies to two-band systems, even if its generalization to more bands is possible. Since there is evidence that in the system under study the inter-band coupling is predominant and the number of bands to be considered is greater than or equal to three35,36, and since using two-band models would lead to the appearance of intra-band terms that do not have a physical interpretation37, we preferred to consider three conducting bands, rather than a more precise parametrization of disorder. Being convinced that this approach is decisive for capturing the essential physics of the material, even if other aspects are unavoidably disregarded, we considered a three-band Eliashberg model, simple enough to allow a meaningful comparison with experimental results. Within this frame, the comparison led us to the awareness that the s± wave model is able to reconcile apparently different evidences, once the impurity scattering role is accounted for.

Techniques

High-quality Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 crystals with an analyzed doping level of x = 0.42 were grown by the FeAs self-flux method26, and cut as thin plates with thickness (along the c-axis) of about 10 μm, much smaller than width and length. Disorder was induced by 250-MeV Au-ion irradiation, with the ion beam parallel to the c-axis of the crystals.

The characterization of the crystals is carried out by a microwave superconducting resonator technique, in a cavity perturbation approach38,39, described in the Methods section, allowing us to determine the critical temperature and the penetration depth of small crystals.

Experimental data are discussed within the s± wave model in the presence of impurity scattering, by comparing them to calculations based on the solution of the three-band Eliashberg equations with suitable input conditions, as detailed below.

Results

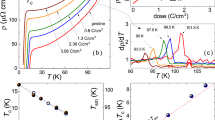

Suppression and broadening of the superconducting transition

A first characterization of the superconducting transition and its modification after irradiation – in terms of temperature and width – can be obtained from rough data, without any model or analysis assumption. The inset in Fig. 1 shows the temperature dependence of the inverse of the unloaded quality factor when the Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 crystal is coupled to the resonator, normalized to its value at T = 40 K (see the Methods section for details). Since 1/Q 0 is proportional to losses, such curves are qualitatively comparable to surface resistance curves. Data are shown for the same crystal before and after subsequent irradiations, up to the fluence of 3.6 × 1012 cm−2. In the mainframe, derivatives are reported, clearly showing that irradiations cause T c suppression and broadening of the transition. More meaningful values of T c , useful for a quantitative comparison with theoretical calculations, will be obtained below after the determination of the penetration depth.

Temperature and width of the superconducting transition, from rough data. The inset shows the temperature dependence of the inverse of the resonator quality factor in the presence of the Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 sample, normalized to its value at T = 40 K. Data are shown for the same crystal before and after subsequent irradiations. In the mainframe, derivatives are reported, showing that irradiations cause T c suppression and transition-width enlargement.

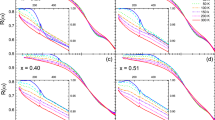

Effects of irradiation on the penetration depth

Figure 2 shows the London penetration depth λ L as a function of temperature, for the same crystal before and after subsequent irradiations. The effect of ion irradiation is both to enhance the λ L values and to modify its temperature dependence. First of all, we investigate the low-temperature behavior of λ L in order to check if it can be understood within the standard scheme described in the Introduction. Data below T/T c = 0.35 are fitted to a power law, Δλ L ∝ T n. Figure 3 reports the exponent n for unirradiated and irradiated samples, as a function of the fluence. Dashed lines indicate reference literature values: an exponent n higher than 3 can be considered to approach the exponential behavior, which is indicative of a fully-gapped clean s-wave state. On the other side, a d-wave state would imply n ≈ 1. In both the cases, the addition of impurity-driven scattering would lead to the dirty limit at n ≈ 2. This is not the trend we observed (symbols), since a smooth decrease from \(n\gg 3\) to n < 1 is clearly shown, as the irradiation fluence is increased. It must be noted that the temperature evolution shown in Fig. 3 is not strictly speaking the low-temperature asymptotic one, that is not accessible by the experiment. Nevertheless, it gives the qualitative indication that a more rigorous theoretical approach is needed to describe the experimental data.

Three-band Eliashberg s± calculations

To understand these results, a comparison with a theoretical model capturing the essential physics of the material is needed. We used a three-band Eliashberg s± wave model in the presence of impurity scattering, with the constraint that both the T c suppression and the λ L (T) behavior were simultaneously explained. The electronic structure of the compound Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 can be approximately described by two hole bands α, β (indicated in the following as bands 1 and 2) and one equivalent electron band γ (indicated in the following as band 3)40. Within the s± wave model, coupling between the electron and the hole bands is due to the antiferromagnetic spin fluctuations, and the gap of the electron band, Δ3, has opposite sign with respect to the gaps of the hole bands, Δ1 and Δ2 1. To calculate the gaps and the critical temperature by the three-band Eliashberg equations41,42,43 one has to solve six coupled equations for the gaps Δ i (iω n ) and the renormalization functions Z i (iω n ), where i is a band index ranging from 1 to 3 and ω n are the Matsubara frequencies (more details in the Methods section). The gaps are assumed to be isotropic due to the low values of anisotropy typical of optimally doped Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 (see also the discussion below). Moreover, considering gap anisotropy would complicate greatly the equations without significantly changing the physics of this system. The calculation is based on the assumption that the nonmagnetic impurity-scattering rates \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{ij}^{N}\) are directly proportional to the defect density that in turn is proportional to the irradiation fluence, while \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{ij}^{N}\) is taken to be zero for the unirradiated crystal. In principle, this introduces a lot of new free parameters (the \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{ij}^{N}\) constants are proportional to the structural disorder in an unknown way). Nevertheless, since the diagonal components \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{ii}^{N}\) do not affect the superconducting properties, we study separately the effects of pair-breaking \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{12}^{N}\), \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{13}^{N}\), and \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\).

For the sake of simplicity, we assume that disorder mainly affects only one of the interband channels. The lines in Fig. 4 represent the solutions of the Eliashberg equations for T c /T c0 with disorder in the channels 12, 13, and 23, respectively, as a function of the scattering rate (lower scale). The experimental data (symbols) are shown as a function of the irradiation fluence (upper scale). The two scales have been adjusted to obtain a good agreement between experimental data and the \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\) curve, giving the scale factor between the fluence and the scattering rate (4.8 × 1014 eV−1 cm−2, in this case). Here the T c value is determined as the temperature where λ L (T) diverges. Attempts to do the same with the \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{12}^{N}\) and \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{13}^{N}\) curves were not successful, i.e. did not lead to proper λ L (T) curves. We conclude here that the main mechanism responsible for T c suppression is radiation-induced increase of the interband scatting rate between bands 2 and 3. Now the energy gaps can be calculated also for the irradiated crystals.

Critical temperature of the irradiated samples, T c , normalized by the critical temperature of the unirradiated sample, T c0, as a function of the interband scattering rate, \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{ij}^{N}\) (lower scale). The lines represent the three possible interband scattering channels, between bands 1, 2 and 3. Experimental data (symbols) are reported as a function of the fluence (upper scale). The upper and lower abscissa have been scaled until data collapsed onto one of the theoretical curves (the scaling factor is 4.8 × 1014 eV−1 cm−2; \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\) was chosen for the reasons described in the text).

In Fig. 5 we report the gaps corresponding to the levels of disorder of the same sample as in Fig. 2, for each irradiation fluence (different colors for the three gaps and different line styles for the different fluences). The left-side panel shows the gap amplitudes obtained by the imaginary-axis solution of the Eliashberg equations. Remarkably, Δ2(T) for the highest fluence changes sign. The right panel of Fig. 5 shows the real-axis low-temperature gap amplitudes, as a function of the interband scattering in the 23 channel. These values, deduced both by the Padé approximants and by a direct calculation on the real axis, are slightly different from the solutions on the imaginary axis, as expected because of the strong coupling regime. For the unirradiated-crystal case, we find gap values that are in fairly good agreement with earlier literature data40. It is confirmed that the low-temperature Δ2 value for the most disordered case is negative, both on the real and on the imaginary axis. It is also shown in Fig. 5 that Δ2 for the most disordered case changes sign as a function of temperature. The change of sign as a function of scattering and/or temperature is worthy to be discussed in more detail.

Left: temperature dependence of the first value of the energy gaps obtained by the solution of the imaginary-axis Eliashberg equations, Δ1 (black), Δ2 (red) and Δ3 (blue) for the unirradiated material (solid lines) and for the material with the same level of disorder as the samples irradiated at the fluences Φ shown in Fig. 2, i.e. Φ = 2.4 × 1012 cm−2 (\({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\) = 4.12 meV, dashed lines), Φ = 2.8 × 1012 cm−2 (\({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\) = 6.07 meV, dotted lines), and Φ = 3.6 × 1012 cm−2 (\({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\) = 8.81 meV, dashed dotted lines). Right: low-temperature values of the gaps from the real-axis solutions of the Eliashberg equations, obtained both by the Padé approximants and by a direct calculation, as a function of the scattering rate (dashed lines are guides to the eye).

A change of sign as a consequence of increased disorder was discussed in refs32,33,34. To qualitatively understand this behavior in our case, it is sufficient to write the Eliashberg equation for the gap Δ2: \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}(i{\omega }_{n})\,{Z}_{2}(i{\omega }_{n})\) = \({\sum }_{m}\,[-{\lambda }_{23}(i{\omega }_{n}-i{\omega }_{m},T)+{{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\,{\delta }_{{\rm{mn}}}]\,{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}(i{\omega }_{m},T)/\sqrt{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}^{2}(i{\omega }_{m},T)+{\omega }_{m}^{2}}\), where λ 23, \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}\) and Z 2 are positive, while Δ2 is negative and δ mn is the Kronecker delta. The presence of disorder brings to an effective coupling (the quantity in the square bracket) that can change sign, resulting in a change of sign also for Δ2.

A sign change as a function of temperature was discussed in ref.44. To understanding this particular effect it is sufficient to consider the previous equation for n = 0: \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}(i{\omega }_{0})\,{Z}_{2}(i{\omega }_{0})\) = \({\sum }_{m}\,[-{\lambda }_{23}(i{\omega }_{0}-i{\omega }_{m},T)\) \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}(i{\omega }_{m},T)/\sqrt{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}^{2}(i{\omega }_{m},T)+{\omega }_{m}^{2}}]\) + \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{23}^{N}{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}(i{\omega }_{0},T)/\sqrt{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}^{2}(i{\omega }_{0},T)+{\omega }_{0}^{2}}\). When the temperature increases, the value of Δ3(iω 0, T) decreases in absolute value. It can happen that the positive first term overcomes the negative second term, resulting in a change from negative to positive sign for Δ2.

Once the gaps and the main model parameters are calculated on the bases of the T c behavior, the penetration depth can be computed by

where ω p,i are the plasma frequencies of the three bands and ω p is the total plasma frequency. Now, we can only act on the weights of the three bands, \({(\tfrac{{\omega }_{p,i}}{{\omega }_{p}})}^{2}\) in order to adapt the calculation to the experimental λ L (T). The best results are reported in Fig. 6, where experimental Δλ L (T) (symbols) are compared to the calculations (lines).

Penetration depth shift Δλ L (t) = λ L (t) − λ L (t = 0.14), where t = T/T c is the reduced temperature. Experimental data (symbols) are compared to model calculations (lines), for the unirradiated sample (Φ = 0) and for the same sample after subsequent irradiations, up to a total fluence Φ = 3.6 × 1012 cm−2. The inset shows the same data in a logarithmic scale.

Discussion and Conclusions

Iron-based superconductors display physical properties which are intimately related to their multiband structure. Since a subtle dependence of these properties on tiny impurity concentrations is expected, the investigation of the role of disorder in such compounds is crucial to achieve a comprehensive understanding. As stated in the Introduction, one of the issue still under debate is the symmetry of the superconducting order parameter, in spite of the huge efforts to conceile experiments with theoretical models. In fact, most of the analysis were done within a simplified two-band model, which is sometimes misleading. Here we have shown that a three-band approach is able to explain in a consistent way the effects of disorder both on T c and on λ L (T), within the s± wave model. Figure 6 shows a remarkable agreement between experiment and theory, in particular the change of curvature in the Δλ L (T) curves for the most irradiated cases is nicely reproduced.

Of course, the calculation still contains approximations and simplifications that could be refined. It is important to resume them and to estimate their possible influence to results. For example, we have found that the irradiation-induced scattering mainly affects the 23 interband channel: the selection of the 23 channel as the most significant follows the analysis of all the channels one by one, that is reasonable in view of a simplicity criterion. However, it cannot be excluded that other more complex combinations of the parameters could describe the experimental results as well, since it is reasonable that also the other channels are somehow modified. Moreover, we did not take into account the finite dimensions of the defects, and the presence of different kinds of defects (as stated in the Introduction, here disorder is treated in the Born approximation). The λ L anisotropy was disregarded (in fact, it is among the lowest for iron-pnictides). Also the gap-anisotropy effect was not considered here. For example, we estimate that, if the smallest gap in k space was much smaller than the smallest average gap on one of the bands, the effect would be a decrease of the two free coupling constants (λ 23 decreases in a more pronounced manner), but the critical temperature would not be affected significantly, since in this case it strongly depends on λ 13. Moreover, this material has already been studied – with good results – with an isotropic model45 and the presence of disorder and the strong coupling regime reduce the impact of gap anisotropy46. Finally, due to the proximity to a magnetic state in such compounds, the possibility of also inducing magnetic scattering by defects cannot be ruled out.

However, from the point of view of computation it is very hard to suitably consider all these aspects, and the adopted model is a good compromise between the need of a reliable tool to explain experimental trends and the need of physical correctness. In this sense, the best agreement between experiment and model shown in Fig. 6 led us to the following conclusions, some of them quantitative and some other only qualitative: (i) for the unirradiated sample, the weights of the three bands 1, 2 and 3 are 0.1, 0.8 and 0.1, respectively38, and the total plasma frequency is ω p = 1 eV, in nice agreement with ref.47; (ii) the weight of the band 1 is not significantly affected by irradiation, while the weight of the band 2 decreases as a function of fluence and the weight of the band 3 increases; (iii) the total plasma frequency decreases as a function of fluence, down to the value of ω p = 0.14 eV for the most irradiated sample, in agreement with the observed increase of λ L in irradiated samples; (iv) also a sub-linear λ L temperature dependence is fully consistent with the s± wave model, if the effects of impurity scattering is suitably taken into account.

Methods

Ion irradiation

Irradiations were performed at room temperature at the Tandem-XTU facility of the LNL laboratories of the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN). The ion beam was parallel to the c-axis of the crystals, and to minimize the heating of the crystals under irradiation, the ion flux was kept below 1.8 × 108 cm−2 s−1. The highest fluence here considered is 3.6 × 1012 cm−2, corresponding to a dose-equivalent field of 72 T. The thickness of all the investigated samples is lower than the longitudinal range of the ions into the material, that is about 14.5 μm, as obtained by SRIM48 and PHITS49 code simulations, using the Kinchin-Pease approach. This guarantees that defects are introduced into the material without contributing extra charge. The overall damage can be computed by the mentioned codes, in terms of d.p.a. (displacements per atom, due to the elastic coulombian scattering against target nuclei), and of the total energy released by ionization. For the present experiment, we obtained the mean d.p.a. value of 7.6 × 10−16 × Φ, and a total energy release by ionization of 2.1 × 1011 × Φ eV cm−3, if the fluence Φ is expressed in cm−2.

Measurements

In order to determine the critical temperature and the penetration depth we used a microwave resonator technique, in a cavity perturbation approach38,39. The resonator is made of a YBa2Cu3O7−x film on MgO substrate, patterned in a coplanar geometry, with a 350-μm-wide central stripline50. The Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 crystal is positioned by a small amount of high-vacuum grease in the center of the stripline, far from edges, i.e. in a region where the rf fields are uniform within about 5%. Measurements of the resonance curve are repeated in the same conditions, with and without the crystal, by means of a Rohde Schwarz ZVK vector network analyzer for an input power of −40 dBm, well below the non-linearity threshold for the resonator. The measurements were carried out in a Cryomech PT 415 pulse tube cooler.

The perturbations relative to no sample coupled to the resonator (rf field parallel to the broad face of the crystal), in terms of resonance frequency f 0 and quality factor Q 0 shifts, are51:

where k is the complex propagation constant and c is the crystal half thickness. Here V s is the volume of the sample and V r is the effective volume of the resonator. The geometrical factor (V s /V r ) is determined in a self-consistent way from data above T c , where the crystals show a metallic behavior. In this case, \({\Re }_{{\mathfrak{e}}}(k)={\Im }_{{\mathfrak{m}}}(k)=1/\delta \) is imposed, where \(\delta =\sqrt{2/\omega \mu \sigma }\) is the classical skin depth. Though most of the field penetrates through the broad faces of the crystals, suitable corrections are applied to account for the field penetration also along the sample thickness, due to the finiteness of the crystals (further details in the Supplementary Information). Once the geometrical factor is obtained, Eqs 2 and 3 allow obtaining the real and imaginary parts of the propagation constant k in the superconducting state, and in turn the London penetration depth λ L and the normal conductivity σ n , that are related to k by52:

The model

As mentioned above, we considered a three-band Eliashberg s± wave model in the presence of impurity scattering, by solving six coupled equations for the gaps Δ i (iω n ) and the renormalization functions Z i (iω n ), where i is a band index ranging from 1 to 3 and ω n are the Matsubara frequencies.

The imaginary-axis equations53,54,55 read:

where \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{ij}}}^{N}\) and \({{\rm{\Gamma }}}_{{\rm{ij}}}^{M}\) are the scattering rates from non-magnetic and magnetic impurities, respectively, \({{\rm{\Lambda }}}_{ij}^{Z}(i{\omega }_{n},i{\omega }_{m})={{\rm{\Lambda }}}_{ij}^{ph}(i{\omega }_{n},i{\omega }_{m})+{{\rm{\Lambda }}}_{ij}^{sf}(i{\omega }_{n},i{\omega }_{m})\) and \({{\rm{\Lambda }}}_{ij}^{{\rm{\Delta }}}(i{\omega }_{n},i{\omega }_{m})={{\rm{\Lambda }}}_{ij}^{ph}(i{\omega }_{n},i{\omega }_{m})-{{\rm{\Lambda }}}_{ij}^{sf}(i{\omega }_{n},i{\omega }_{m})\) where

Θ is the Heaviside function and ω c is a cutoff energy. The quantities \({\mu }_{ij}^{\ast }({\omega }_{{\rm{c}}})\) are the elements of the 3 × 3 Coulomb pseudopotential matrix. Finally, \({N}_{j}^{{\rm{\Delta }}}(i{\omega }_{m})={{\rm{\Delta }}}_{j}(i{\omega }_{m})/\sqrt{{\omega }_{m}^{2}+{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{j}^{2}(i{\omega }_{m})}\) and \({N}_{j}^{Z}(i{\omega }_{m})={\omega }_{m}/\sqrt{{\omega }_{m}^{2}+{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{j}^{2}(i{\omega }_{m})}\).

The electron-boson coupling constants are defined as \({\lambda }_{ij}^{ph,sf}=2\,{\int }_{0}^{+\infty }\,d{\rm{\Omega }}\tfrac{{\alpha }_{ij}^{2}{F}^{ph,sf}({\rm{\Omega }})}{{\rm{\Omega }}}\). The solution of Eqs 4 and 5 requires a huge number of input parameters that can be taken from literature or fixed by suitable approximations (further details in the Supplementary Information). Then the critical temperature can be calculated, which turns out to be in agreement with the experimental one, once the “feedback” effect56 of the electronic condensate on the antiferromagnetic spin fluctuations has been taken into account. The critical temperatures of the irradiated crystals are reproduced by setting a suitable non-zero interband scatting rate, as described above, in the Results section.

References

Mazin, I. I., Singh, D. J., Johannes, M. D. & Du, M. H. Unconventional superconductivity with a sign reversal in the order parameter of LaFeAsO1−x Fx. Physical Review Letters 101, 057003, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.101.057003 (2008).

Chubukov, A. V., Efremov, D. V. & Eremin, I. Magnetism, superconductivity, and pairing symmetry in iron-based superconductors. Physical Review B 78, 134512, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.78.134512 (2008).

Kirshenbaum, K., Saha, S. R., Ziemak, S., Drye, T. & Paglione, J. Universal pair-breaking in transition-metal-substituted iron-pnictide superconductors. Physical Review B 86, 140505(R), https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.140505 (2012).

Fernandes, R. M., Vavilov, M. G. & Chubukov, A. V. Enhancement of T c by disorder in underdoped iron pnictide superconductors. Physical Review B 85, 140512(R), https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.85.140512 (2012).

Onari, S., Kontani, H. & Sato, M. Structure of neutron-scattering peaks in both s++- wave and s± -wave states of an iron pnictide superconductor. Physical Review B 81, 060504(R), https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.81.060504 (2010).

Efremov, D. V., Korshunov, M. M., Dolgov, O. V., Golubov, A. A. & Hirschfeld, P. J. Disorder-induced transition between s± and s++ states in two-band superconductors. Physical Review B 84, 180512(R), https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.84.180512 (2011).

Wang, Y., Kreisel, A., Hirschfeld, P. J. & Mishra, V. Using controlled disorder to distinguish s± and s++ gap structure in fe-based superconductors. Physical Review B 87, 094504, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.87.094504 (2013).

Schilling, M. B. et al. Tracing the s± symmetry in iron pnictides by controlled disorder. Physical Review B 93, 174515, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.93.174515 (2016).

Cho, K. et al. Energy gap evolution across the superconductivity dome in single crystals of (Ba1−x K x )Fe2As2. Science Advances 2, e1600807, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600807 (2016).

Prozorov, R. et al. Effect of electron irradiation on superconductivity in single crystals of Ba(Fe1−x Ru x )2As2 (x = 0.24). Journal = Physical Review X 4, 041032, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevx.4.041032 (2014).

Bang, Y. & Stewart, G. R. Superconducting properties of the s± -wave state: Fe-based superconductors. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 29, 123003, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648x/aa564b (2017).

Karakozov, A. E. et al. Temperature dependence of the superfluid density as a probe for multiple gaps in Ba(Fe0.9Co0.1)2As2: Manifestation of three weakly interacting condensates. Physical Review B 90, 014506, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.90.014506 (2014).

Prozorov, R. & Kogan, V. G. London penetration depth in iron-based superconductors. Reports on Progress in Physics 74, 124505, https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/74/12/124505 (2011).

Mishra, V. et al. Lifting of nodes by disorder in extended-s-state superconductors: Application to ferropnictides. Physical Review B 79, 094512, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.79.094512 (2009).

Karkin, A. E., Werner, J., Behr, G. & Goshchitskii, B. N. Neutron-irradiation effects in polycrystalline LaFeAsO0.9F0.1 superconductors. Physical Review B 80, 174512, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.80.174512 (2009).

Tarantini, C. et al. Suppression of the critical temperature of superconducting NdFeAs(OF) single crystals by Kondo-like defect sites induced by α-particle irradiation. Physical Review Letters 104, 087002, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.104.087002 (2010).

Cho, K. et al. Effects of electron irradiation on resistivity and london penetration depth of Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 (x ≤ 0.34) iron-pnictide superconductor. Physical Review B 90, 104514, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.90.104514 (2014).

Mizukami, Y. et al. Disorder-induced topological change of the superconducting gap structure in iron pnictides. Nature Communications 5, 5657, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6657 (2014).

Tamegai, T. et al. Effects of particle irradiations on vortex states in iron-based superconductors. Superconductor Science and Technology 25, 084008, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/25/8/084008 (2012).

Laviano, F. et al. Evidence of anisotropic vortex pinning by intrinsic and irradiation-induced defects in Ba(Fe,Co)2As2 studied by quantitative magneto-optical imaging. Superconductor Science and Technology 27, 044014, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/27/4/044014 (2014).

Haberkorn, N. et al. Increment of the collective pinning energy in Na1−x Ca x Fe2As2 single crystals with random point defects introduced by proton irradiation. Superconductor Science and Technology 27, 095004, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/27/9/095004 (2014).

Ohtake, F., Taen, T., Pyon, S., Tamegai, T. & Okayasu, S. The effect of 320 MeV au irradiation in K-doped ba-122. Physics Procedia 58, 122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2014.09.046 (2014).

Kihlstrom, K. J. et al. High-field critical current enhancement by irradiation induced correlated and random defects in (Ba0.6K0.2)Fe2As2. Applied Physics Letters 103, 202601, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4829524 (2013).

Taen, T. et al. Effects of irradiation-particle energy on critical current density in Co-doped BaFe2As2. Physica C: Superconductivity 484, 62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physc.2012.02.040 (2013).

Nakajima, Y. et al. Suppression of the critical temperature of superconducting Ba(Fe1−x Co x )2As2 by point defects from proton irradiation. Physical Review B 82, 220504(R), https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.82.220504 (2010).

Taen, T. et al. Pair-breaking effects induced by 3-MeV proton irradiation in Ba1−x K x Fe2As2. Physical Review B 88, 224514, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.88.224514 (2013).

Nakajima, Y. et al. Enhancement of critical current density in Co-doped BaFe2As2 with columnar defects introduced by heavy-ion irradiation. Physical Review B 80, 012510, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.80.012510 (2009).

Massee, F. et al. Imaging atomic-scale effects of high-energy ion irradiation on superconductivity and vortex pinning in Fe(Se, Te). Science Advances 1, e1500033, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500033 (2015).

Gozzelino, L., Gerbaldo, R., Ghigo, G., Laviano, F. & Tamegai, T. Effects of 250 MeV au-ion irradiation on the superconducting properties of Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 single crystals. MRS Advances 1, 3447, https://doi.org/10.1557/adv.2016.428 (2016).

Laviano, F. et al. Evidence of vortex curvature and anisotropic pinning in superconducting films by quantitative magneto-optics. Physical Review B 68, 014507, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.68.014507 (2003).

Allen, P. B. & Mitrović, B. Theory of superconducting Tc. Solid State Physics 37, 1–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0081-1947(08)60665-7 (1983).

Efremov, D., Golubov, A. & Dolgov, O. Manifestations of impurity-induced s± s++ transition: multiband model for dynamical response functions. New journal of physics 15, 013002, https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/15/1/013002 (2013).

Efremov, D., Korshunov, M., Dolgov, O., Golubov, A. A. & Hirschfeld, P. Disorder-induced transition between s± and s++ states in two-band superconductors. Physical Review B 84, 180512, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.180512 (2011).

Korshunov, M. M., Togushova, Y. N. & Dolgov, O. V. Impurities in multiband superconductors. Physics-Uspekhi 59, 1211, https://doi.org/10.3367/UFNe.2016.07.037863 (2016).

Mazin, I. & Schmalian, J. Pairing symmetry and pairing state in ferropnictides: Theoretical overview. Physica C: Superconductivity 469, 614–627, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physc.2009.03.019 (2009).

Boeri, L., Calandra, M., Mazin, I. I., Dolgov, O. V. & Mauri, F. Effects of magnetism and doping on the electron-phonon coupling in BaFe2AS2. Physical Review B 82, 020506, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.82.020506 (2010).

Charnukha, A. et al. Eliashberg approach to infrared anomalies induced by the superconducting state of Ba0.68K0.32Fe2As2 single crystals. Physical Review B 84, 174511, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.174511 (2011).

Ghigo, G., Ummarino, G., Gozzelino, L. & Tamegai, T. Penetration depth of Ba1−x K x Fe2As2 single crystals explained within a multiband Eliashberg s± approach. Physical Review B 96, 014501, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.014501 (2017).

Ghigo, G., Gerbaldo, R., Gozzelino, L., Laviano, F. & Tamegai, T. Penetration depth and quasiparticle conductivity of Co- and K-doped BaFe2As2 crystals, investigated by a microwave coplanar resonator technique. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 26, 1, https://doi.org/10.1109/tasc.2016.2529419 (2016).

Ding, H. et al. Observation of fermi-surface–dependent nodeless superconducting gaps in (Ba0.6K0.4)Fe2As2. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 83, 47001, https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/83/47001 (2008).

Eliashberg, G. Interactions between electrons and lattice vibrations in a superconductor. Sov. Phys. JETP 11, 696–702 (1960).

Chubukov, A., Pines, D., Schmalian, J., KH, B. & Ketterson, J. A spin fluctuation model for d-wave superconductivity. In Superconductivity: Volume 1: Conventional and Unconventional Superconductors Volume 2: Novel Superconductors, 1349–1413 (Springer, 2008).

Manske, D., Eremin, I., Bennemann, K. & Ketterson, J. Electronic theory for superconductivity in high-T c cuprates and Sr2RuO4. In Superconductivity: Volume 1: Conventional and Unconventional Superconductors Volume 2: Novel Superconductors, 1415–1515 (Springer, 2008).

Ummarino, G. Iron-based layered compounds: the effect of negative interband coupling. Journal of superconductivity and novel magnetism 22, 603–607, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-009-0459-8 (2009).

Popovich, P. et al. Specific heat measurements of Ba0.68K0.32Fe2As2 single crystals: evidence for a multiband strong-coupling superconducting state. Physical review letters 105, 027003, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.027003 (2010).

Dolgov, O. & Golubov, A. A. Strong electron-phonon interaction in multiband superconductors. Physical Review B 77, 214526, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.214526 (2008).

Hwang, J. Electron–boson spectral density function of correlated multiband systems obtained from optical data: (Ba0.6K0.4)Fe2As2 and LiFeAs. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 28, 125702, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/28/12/125702 (2016).

Ziegler, J. F., Ziegler, M. & Biersack, J. SRIM – the stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 268, 1818–1823, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2010.02.091 (2010).

Sato, T. et al. Particle and Heavy Ion Transport code System, PHITS, version 2.52. Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology 50, 913–923, https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2013.814553 (2013).

Ghigo, G., Laviano, F., Gerbaldo, R. & Gozzelino, L. Tuning the response of YBCO microwave resonators by heavy-ion patterned micro-channels. Superconductor Science and Technology 25, 115007, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/25/11/115007 (2012).

Hardy, W. N., Bonn, D. A., Morgan, D. C., Liang, R. & Zhang, K. Precision measurements of the temperature dependence of λ in YBa2Cu3O6.95: Strong evidence for nodes in the gap function. Physical Review Letters 70, 3999–4002, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.70.3999 (1993).

Vendik, I. Phenomenological model of the microwave surface impedance of high-T c superconducting films. Superconductor Science and Technology 13, 974–982, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/13/7/312 (2000).

Ummarino, G. A. Multiband s± Eliashberg theory and temperature-dependent spin-resonance energy in iron pnictide superconductors. Physical Review B 83, 092508, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.83.092508 (2011).

Ummarino, G. A., Tortello, M., Daghero, D. & Gonnelli, R. S. Three-band s± Eliashberg theory and the superconducting gaps of iron pnictides. Physical Review B 80, 172503, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.80.172503 (2009).

Ummarino, G. A., Daghero, D., Tortello, M. & Gonnelli, R. S. Predictions of multiband s± strong-coupling Eliashberg theory compared to experimental data in iron pnictides. Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism 24, 247–253, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-010-1006-3 (2010).

Ummarino, G. A. Effects of magnetic impurities on two-band superconductor. Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism 20, 639–642, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-007-0259-y (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by MIUR-PRIN2012 Project No. 2012X3YFZ2. The irradiations were performed in the framework of the INFN-Politecnico di Torino M.E.S.H. Research Agreement. G.A.U. acknowledges support from the MEPhI Academic Excellence Project (Contract No. 02.a03.21.0005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.G. conceived the experiment and made the microwave characterizations, G.A.U. made the Eliashberg calculations, and T.T. fabricated the samples. Irradiations were performed by G.G., L.G., R.G. and F.L., and D.T. contributed to data analysis. Damage simulations were done by L.G. and D.T. All the authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghigo, G., Ummarino, G.A., Gozzelino, L. et al. Effects of disorder induced by heavy-ion irradiation on (Ba1−x K x )Fe2As2 single crystals, within the three-band Eliashberg s± wave model. Sci Rep 7, 13029 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13303-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13303-5

This article is cited by

-

Nodal multigap superconductivity in the anisotropic iron-based compound RbCa2Fe4As4F2

npj Quantum Materials (2022)

-

Scaling laws for ion irradiation effects in iron-based superconductors

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Eliashberg Analysis of the Electrodynamic Response of Ba(Fe1−xRhx)2As2 Across the s± to s++ Order Parameter Transition

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2020)

-

Tuning electric charge scattering in YBCO single crystals via irradiation with MeV electrons

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2019)

-

Suppression of vortex lattice melting in YBCO via irradiation with fast electrons

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.