Abstract

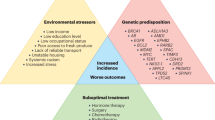

Prostate cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed non-skin malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer death among men in the USA. However, the mortality rate of African American men aged 40–60 years is almost 2.5-fold greater than that of European American men. Despite screening and diagnostic and therapeutic advances, disparities in prostate cancer incidence and outcomes remain prevalent. The reasons that lead to this disparity in outcomes are complex and multifactorial. Established non-modifiable risk factors such as age and genetic predisposition contribute to this disparity; however, evidence suggests that modifiable risk factors (including social determinants of health, diet, steroid hormones, environment and lack of diversity in enrolment in clinical trials) are prominent contributing factors to the racial disparities observed. Disparities involved in the diagnosis, treatment and survival of African American men with prostate cancer have also been correlated with low socioeconomic status, education and lack of access to health care. The effects and complex interactions of prostate cancer modifiable risk factors are important considerations for mitigating the incidence and outcomes of this disease in African American men.

Key points

-

Current data emphasize the need for the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to re-evaluate their guidelines by recommending prostate cancer screening in high-risk populations to attenuate the upward trends of prostate cancer fatalities and reduce disparities.

-

2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhiP)–DNA adducts can facilitate mutagenesis that may result in tumorigenesis. Data suggest that African American men might have diets that include higher amounts of red meat and sources of PhiP than European American men, contributing to the prostate cancer disparities observed.

-

Vitamin D deficiency has been shown to be associated with aggressive prostate cancer and mortality, especially in African American men. Elucidating vitamin D signalling pathways that underlie prostate carcinogenesis might aid mitigation of prostate cancer disparities between African American and European American men.

-

Glucocorticoid receptors have emerged as a major driver of prostate cancer progression and resistance to treatments. Clinicians must consider the possibility of differential responses to prostate cancer treatments, including glucocorticoid treatments in African American men.

-

Increasing the number of studies investigating immunity and inflammatory regulation in prostate tumours and adjacent tumour microenvironment is imperative for high-risk under-represented populations.

-

Sensitive and strategic initiatives to advance inclusive research are needed to increase clinical trial participation by minority individuals.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48 (2023).

Woods-Burnham, L. et al. Psychosocial stress, glucocorticoid signaling, and prostate cancer health disparities in African American men. Cancer Health Disparities 4, https://companyofscientists.com/index.php/chd/article/view/169/188 (2023).

Powell, I. J., Vigneau, F. D., Bock, C. H., Ruterbusch, J. & Heilbrun, L. K. Reducing prostate cancer racial disparity: evidence for aggressive early prostate cancer PSA testing of African American men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 23, 1505–1511 (2014).

Giri, V. N. et al. Race, genetic West African ancestry, and prostate cancer prediction by prostate-specific antigen in prospectively screened high-risk men. Cancer Prev. Res. 2, 244–250 (2009).

Chornokur, G., Dalton, K., Borysova, M. E. & Kumar, N. B. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate 71, 985–997 (2011).

Loree, J. M. et al. Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 5, e191870 (2019).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

McGinley, K. F., Tay, K. J. & Moul, J. W. Prostate cancer in men of African origin. Nat. Rev. Urol. 13, 99–107 (2016).

National Cancer Institute. SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. NCI https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html (2023).

Powell, I. J. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of prostate cancer in African-American men. J. Urol. 177, 444–449 (2007).

Milonas, D., Venclovas, Z. & Jievaltas, M. Age and aggressiveness of prostate cancer: analysis of clinical and pathological characteristics after radical prostatectomy for men with localized prostate cancer. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 72, 240–246 (2019).

Jahn, J. L., Giovannucci, E. L. & Stampfer, M. J. The high prevalence of undiagnosed prostate cancer at autopsy: implications for epidemiology and treatment of prostate cancer in the prostate-specific antigen era. Int. J. Cancer 137, 2795–2802 (2015).

He, T. & Mullins, C. D. Age-related racial disparities in prostate cancer patients: a systematic review. Ethn. Health 22, 184–195 (2017).

Guo, J. et al. Establishing a urine-based biomarker assay for prostate cancer risk stratification. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 597961 (2020).

Fenton, J. J. et al. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 319, 1914–1931 (2018).

Barry, M. J. & Simmons, L. H. Prevention of prostate cancer morbidity and mortality: primary prevention and early detection. Med. Clin. North. Am. 101, 787–806 (2017).

Jansen, F. H. et al. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) isoform p2PSA in combination with total PSA and free PSA improves diagnostic accuracy in prostate cancer detection. Eur. Urol. 57, 921–927 (2010).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or =4.0 ng per milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2239–2246 (2004).

Barry, M. J. Clinical practice. Prostate-specific-antigen testing for early diagnosis of prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1373–1377 (2001).

Moyer, V. A. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 157, 120–134 (2012).

Bibbins-Domingo, K., Grossman, D. C. & Curry, S. J. The US Preventive Services Task Force 2017 draft recommendation statement on screening for prostate cancer: an invitation to review and comment. JAMA 317, 1949–1950 (2017).

US Preventive Services Task Force.Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 319, 1901–1913 (2018).

American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html (2021).

Smith, R. A. et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: a review of current american cancer society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 297–316 (2018).

Prostate Cancer Foundation. The Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test. https://www.pcf.org/about-prostate-cancer/what-is-prostate-cancer/the-psa-test/ (2021).

Preston, D. M. et al. Prostate-specific antigen levels in young white and black men 20 to 45 years old. Urology 56, 812–816 (2000).

Saini, S. PSA and beyond: alternative prostate cancer biomarkers. Cell. Oncol. 39, 97–106 (2016).

Foundation, P. C. The Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test. https://www.pcf.org/about-prostate-cancer/what-is-prostate-cancer/the-psa-test/ (2022).

Shenoy, D., Packianathan, S., Chen, A. M. & Vijayakumar, S. Do African-American men need separate prostate cancer screening guidelines? BMC Urol. 16, 19 (2016).

Tsodikov, A. et al. Is prostate cancer different in Black men? Answers from 3 natural history models. Cancer 123, 2312–2319 (2017).

Shah, N., Ioffe, V. & Chang, J. C. Increasing aggressive prostate cancer. Can. J. Urol. 29, 11384–11390 (2022).

Becker, D. J. et al. The association of veterans’ PSA screening rates with changes in USPSTF recommendations. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 113, 626–631 (2021).

Danan, E. R., White, K. M., Wilt, T. J. & Partin, M. R. Reactions to recommendations and evidence about prostate cancer screening among White and Black male veterans. Am. J. Men’s Health 15, 15579883211022110 (2021).

Wu, I. & Modlin, C. S. Disparities in prostate cancer in African American men: what primary care physicians can do. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 79, 313–320 (2012).

Dess, R. T. et al. Association of Black race with prostate cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 5, 975–983 (2019).

Schumacher, F. R. et al. Race and genetic alterations in prostate cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 5, PO.21.00324 (2021).

Chowdhury-Paulino, I. M. et al. Racial disparities in prostate cancer among black men: epidemiology and outcomes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 25, 397–402 (2022).

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. Social Determinants of Health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (2020).

Weprin, S. A. et al. Association of low socioeconomic status with adverse prostate cancer pathology among African American who underwent radical prostatectomy. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 17, e1054–e1059 (2019).

Orom, H., Biddle, C., Underwood, W. III, Homish, G. G. & Olsson, C. A. Racial or ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in prostate cancer survivors’ prostate-specific quality of life. Urology 112, 132–137 (2018).

Lillie-Blanton, M. & Hoffman, C. The role of health insurance coverage in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in health care. Health Aff. 24, 398–408 (2005).

Clouston, S. A. P. & Link, B. G. A retrospective on fundamental cause theory: state of the literature, and goals for the future. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 47, 131–156 (2021).

Kirby, J. B., Taliaferro, G. & Zuvekas, S. H. Explaining racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Med. Care 44, I64–I72 (2006).

Mahal, A. R., Mahal, B. A., Nguyen, P. L. & Yu, J. B. Prostate cancer outcomes for men aged younger than 65 years with Medicaid versus private insurance. Cancer 124, 752–759 (2018).

Watson, M. et al. Racial differences in prostate cancer treatment: the role of socioeconomic status. Ethn. Dis. 27, 201–208 (2017).

El Khoury, C. J. & Clouston, S. A. P. Racial/ethnic disparities in prostate cancer 5-year survival: the role of health-care access and disease severity. Cancers 15, 4284 (2023).

Braveman, P. A., Cubbin, C., Egerter, S., Williams, D. R. & Pamuk, E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am. J. Public. Health 100, S186–S196 (2010).

Farmer, M. M. & Ferraro, K. F. Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status. Soc. Sci. Med. 60, 191–204 (2005).

Paller, C. J., Wang, L. & Brawley, O. W. Racial inequality in prostate cancer outcomes — socioeconomics, not biology. JAMA Oncol. 5, 983–984 (2019).

Vince, R. A. Jr et al. Evaluation of social determinants of health and prostate cancer outcomes among Black and White patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2250416 (2023).

Lu, C. D. et al. Racial disparities in prostate specific antigen screening and referral to urology in a large, integrated health care system: a retrospective cohort study. J. Urol. 206, 270–278 (2021).

Barocas, D. A. et al. Association between race and follow-up diagnostic care after a positive prostate cancer screening test in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Cancer 119, 2223–2229 (2013).

Hayn, M. H. et al. Racial/ethnic differences in receipt of pelvic lymph node dissection among men with localized/regional prostate cancer. Cancer 117, 4651–4658 (2011).

Underwood, W. III et al. Racial treatment trends in localized/regional prostate carcinoma: 1992–1999. Cancer 103, 538–545 (2005).

Gilligan, T., Wang, P. S., Levin, R., Kantoff, P. W. & Avorn, J. Racial differences in screening for prostate cancer in the elderly. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 1858–1864 (2004).

Institute of Medicine et al. (eds Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y. & Nelson, A. R.) Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (National Academies Press, 2002).

Press, D. J. et al. Contributions of social factors to disparities in prostate cancer risk profiles among Black men and non-hispanic White men with prostate cancer in California. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 31, 404–412 (2022).

Iyer, H. S. et al. Influence of neighborhood social and natural environment on prostate tumor histology in a cohort of male health professionals. Am. J. Epidemiol. 192, 1485–1498 (2023).

DeRouen, M. C. et al. Disparities in prostate cancer survival according to neighborhood archetypes, a population-based study. Urology 163, 138–147 (2022).

Matsushita, M., Fujita, K. & Nonomura, N. Influence of diet and nutrition on prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1447 (2020).

Lin, P.-H., Aronson, W. & Freedland, S. J. Nutrition, dietary interventions and prostate cancer: the latest evidence. BMC Med. 13, 3 (2015).

Rohrmann, S. et al. Meat and dairy consumption and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in a US cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 18, 41–50 (2007).

Major, J. M. et al. Patterns of meat intake and risk of prostate cancer among African-Americans in a large prospective study. Cancer Causes Control 22, 1691–1698 (2011).

Cross, A. J. et al. A prospective study of meat and meat mutagens and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 65, 11779–11784 (2005).

Zhang, W. & Zhang, K. Quantifying the contributions of environmental factors to prostate cancer and detecting risk-related diet metrics and racial disparities. Cancer Inf. 22, 11769351231168006 (2023).

Mirahmadi, M. et al. Potential inhibitory effect of lycopene on prostate cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 129, 110459 (2020).

Saini, R. K., Rengasamy, K. R. R., Mahomoodally, F. M. & Keum, Y. S. Protective effects of lycopene in cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases: an update on epidemiological and mechanistic perspectives. Pharmacol. Res. 155, 104730 (2020).

Giovannucci, E., Rimm, E. B., Liu, Y., Stampfer, M. J. & Willett, W. C. A prospective study of tomato products, lycopene, and prostate cancer risk. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 94, 391–398 (2002).

Kirsh, V. A. et al. Supplemental and dietary vitamin E, beta-carotene, and vitamin C intakes and prostate cancer risk. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 98, 245–254 (2006).

Schuurman, A. G., Goldbohm, R. A., Brants, H. A. & van den Brandt, P. A. A prospective cohort study on intake of retinol, vitamins C and E, and carotenoids and prostate cancer risk (Netherlands). Cancer Causes Control 13, 573–582 (2002).

Kristal, A. R. & Cohen, J. H. Invited commentary: tomatoes, lycopene, and prostate cancer. How strong is the evidence? Am. J. Epidemiol. 151, 124–127 (2000).

Lu, Y. et al. Insufficient lycopene intake is associated with high risk of prostate cancer: a cross-sectional study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2003–2010). Front. Public Health 9, 792572 (2021).

Batai, K. M. et al. Race and BMI modify associations of calcium and vitamin D intake with prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 17, 64 (2017).

Poirier, M. C. Chemical-induced DNA damage and human cancer risk. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 630–637 (2004).

Turesky, R. J. & Le Marchand, L. Metabolism and biomarkers of heterocyclic aromatic amines in molecular epidemiology studies: lessons learned from aromatic amines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 24, 1169–1214 (2011).

Bylsma, L. C. & Alexander, D. D. A review and meta-analysis of prospective studies of red and processed meat, meat cooking methods, heme iron, heterocyclic amines and prostate cancer. Nutr. J. 14, 125 (2015).

Christensen, B. C. et al. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000602 (2009).

Sinha, R. et al. Meat and meat-related compounds and risk of prostate cancer in a large prospective cohort study in the United States. Am. J. Epidemiol. 170, 1165–1177 (2009).

Koutros, S. et al. Meat and meat mutagens and risk of prostate cancer in the Agricultural Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 17, 80–87 (2008).

Punnen, S., Hardin, J., Cheng, I., Klein, E. A. & Witte, J. S. Impact of meat consumption, preparation, and mutagens on aggressive prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 6, e27711 (2011).

Esumi, H., Ohgaki, H., Kohzen, E., Takayama, S. & Sugimura, T. Induction of lymphoma in CDF1 mice by the food mutagen, 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine. Jpn J. Cancer Res. 80, 1176–1178 (1989).

Ghoshal, A., Preisegger, K. H., Takayama, S., Thorgeirsson, S. S. & Snyderwine, E. G. Induction of mammary tumors in female Sprague–Dawley rats by the food-derived carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and effect of dietary fat. Carcinogenesis 15, 2429–2433 (1994).

Hasegawa, R. et al. Dose-dependence of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]-pyridine (PhIP) carcinogenicity in rats. Carcinogenesis 14, 2553–2557 (1993).

Boccon-Gibod, L. et al. Flutamide versus orchidectomy in the treatment of metastatic prostate carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 32, 391–395 (1997).

Stuart, G. R., Holcroft, J., de Boer, J. G. & Glickman, B. W. Prostate mutations in rats induced by the suspected human carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine. Cancer Res. 60, 266–268 (2000).

Bellamri, M., Xiao, S., Murugan, P., Weight, C. J. & Turesky, R. J. Metabolic activation of the cooked meat carcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine in human prostate. Toxicol. Sci. 163, 543–556 (2018).

Di Paolo, O. A., Teitel, C. H., Nowell, S., Coles, B. F. & Kadlubar, F. F. Expression of cytochromes P450 and glutathione S-transferases in human prostate, and the potential for activation of heterocyclic amine carcinogens via acetyl-coA-, PAPS- and ATP-dependent pathways. Int. J. Cancer 117, 8–13 (2005).

Bai, X. Y. et al. Blockade of hedgehog signaling synergistically increases sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE 11, e0149370 (2016).

Keating, G. A. & Bogen, K. T. Estimates of heterocyclic amine intake in the US population. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 802, 127–133 (2004).

Rodriguez, C. et al. Meat consumption among Black and White men and risk of prostate cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 15, 211–216 (2006).

Awada, A. et al. The oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in combination with letrozole in patients with advanced breast cancer: results of a phase I study with pharmacokinetics. Eur. J. Cancer 44, 84–91 (2008).

Bray, G. A. & Popkin, B. M. Dietary sugar and body weight: have we reached a crisis in the epidemic of obesity and diabetes? health be damned! Pour on the sugar. Diabetes Care 37, 950–956 (2014).

Freedland, S. J. & Platz, E. A. Obesity and prostate cancer: making sense out of apparently conflicting data. Epidemiol. Rev. 29, 88–97 (2007).

Barrington, W. E. et al. Difference in association of obesity with prostate cancer risk between US African American and non-hispanic white men in the selenium and vitamin E cancer prevention trial (SELECT). JAMA Oncol. 1, 342–349 (2015).

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Fryar, C. D. & Legal, K. M. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief No. 219 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db219.pdf (2015).

Murphy, A. B. et al. Vitamin D deficiency predicts prostate biopsy outcomes. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 2289–2299 (2014).

Nelson SM, B. K., Ahaghotu, C., Agurs-Collins, T. & Kittles, R. A. Association between serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D and aggressive prostate cancer in African American Men. Nutrients 9, 12 (2016).

Schwartz, G. G. Vitamin D and the epidemiology of prostate cancer. Semin. Dialysis 18, 276–289 (2005).

Murphy, A. B. et al. Predictors of serum vitamin D levels in African American and European American men in Chicago. Am. J. Mens. Health 6, 420–426 (2012).

Travis, R. C. et al. A collaborative analysis of individual participant data from 19 prospective studies assesses circulating vitamin D and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 79, 274–285 (2019).

Bassuk, S. S., Chandler, P. D., Buring, J. E. & Manson, J. E. The vitamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL): do results differ by sex or race/ethnicity. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 15, 372–391 (2021).

Christakos, S., Dhawan, P., Verstuyf, A., Verlinden, L. & Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D: metabolism, molecular mechanism of action, and pleiotropic effects. Physiol. Rev. 96, 365–408 (2016).

Boyle, B. J., Zhao, X.-Y., Cohen, P. & Feldman, D. insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 mediates 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 growth inhibition in the lncap prostate cancer cell line through P21/WAF1. J. Urol. 165, 1319–1324 (2001).

Mantell, D., Owens, P., Bundred, N., Mawer, E. & Canfield, A. 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Circ. Res. 87, 214–220 (2000).

Bao, B.-Y., Yeh, S.-D. & Lee, Y.-F. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D 3 inhibits prostate cancer cell invasion via modulation of selective proteases. Carcinogenesis 27, 32–42 (2005).

Krishnan, A. V. & Feldman, D. Molecular pathways mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of calcitriol: implications for prostate cancer chemoprevention and treatment. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 17, R19–R38 (2010).

Blutt, S. E., McDonnell, T. J., Polek, T. C. & Weigel, N. L. Calcitriol-induced apoptosis in LNCaP cells is blocked by overexpression of Bcl-2. Endocrinology 141, 10–17 (2000).

McCray, T. et al. Vitamin D sufficiency enhances differentiation of patient-derived prostate epithelial organoids. iScience 24, 101974 (2021).

Gaston, K. E., Kim, D., Singh, S., Ford, O. H. III & Mohler, J. L. Racial differences in androgen receptor protein expression in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. J. Urol. 170, 990–993 (2003).

Miller, G. J. et al. The human prostatic carcinoma cell line LNCaP expresses biologically active, specific receptors for 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Cancer Res. 52, 515–520 (1992).

Zhao, X. Y. & Feldman, D. The role of vitamin D in prostate cancer. Steroids 66, 293–300 (2001).

Garcia, J. et al. Regulation of prostate androgens by megalin and 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: mechanism for high prostate androgens in African American men. Cancer Res. Commun. 3, 371–382 (2023).

Siddappa, M. et al. African american prostate cancer displays quantitatively distinct vitamin D receptor cistrome–transcriptome relationships regulated by BAZ1A. Cancer Res. Commun. 3, 621–639 (2023).

Hardiman, G. et al. Systems analysis of the prostate transcriptome in African-American men compared with European-American men. Pharmacogenomics 17, 1129–1143 (2016).

Carlberg, C. & Haq, A. The concept of the personal vitamin D response index. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 175, 12–17 (2018).

Frazier, B., Hsiao, C. W., Deuster, P. & Poth, M. African Americans and Caucasian Americans: differences in glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance. Horm. Metab. Res. 42, 887–891 (2010).

Cohen, S. et al. Socioeconomic status, race, and diurnal cortisol decline in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Psychosom. Med. 68, 41–50 (2006).

Zannas, A. S. et al. Lifetime stress accelerates epigenetic aging in an urban, African American cohort: relevance of glucocorticoid signaling. Genome Biol. 16, 266 (2015).

Zannas, A. S. & West, A. E. Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience 264, 157–170 (2014).

Arora, V. K. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor confers resistance to antiandrogens by bypassing androgen receptor blockade. Cell 155, 1309–1322 (2013).

Isikbay, M. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor activity contributes to resistance to androgen-targeted therapy in prostate cancer. Hormones cancer 5, 72–89 (2014).

Woods-Burnham, L. et al. Glucocorticoids induce stress oncoproteins associated with therapy-resistance in African American and European American prostate cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 8, 15063 (2018).

Perletti, G. et al. The association between prostatitis and prostate cancer. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 89, 259–265 (2017).

Nesi, G., Nobili, S., Cai, T., Caini, S. & Santi, R. Chronic inflammation in urothelial bladder cancer. Virchows Arch. 467, 623–633 (2015).

Batai, K., Murphy, A. B., Nonn, L. & Kittles, R. A. Vitamin D and immune response: implications for prostate cancer in African Americans. Front. Immunol. 7, 53 (2016).

Powell, I. J. & Bollig-Fischer, A. Minireview: the molecular and genomic basis for prostate cancer health disparities. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 879–891 (2013).

Kinseth, M. A. et al. Expression differences between African American and Caucasian prostate cancer tissue reveals that stroma is the site of aggressive changes. Int. J. Cancer 134, 81–91 (2014).

Yamoah, K. et al. Prostate tumors of native men from West Africa show biologically distinct pathways — a comparative genomic study. Prostate 81, 1402–1410 (2021).

A. Oliver Sartor, A. J. A. et al. Overall survival (OS) of African-American (AA) and Caucasian (CAU) men who received sipuleucel-T for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): final PROCEED analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 5035 (2019).

Johnson, J. R. & Kittles, R. A. Genetic ancestry and racial differences in prostate tumours. Nat. Rev. Urol. 19, 133–134 (2022).

Gillard, M. et al. Elevation of stromal-derived mediators of inflammation promote prostate cancer progression in African-American men. Cancer Res. 78, 6134–6145 (2018).

Montiel Ishino, F. A. et al. Sociodemographic and geographic disparities of prostate cancer treatment delay in Tennessee: a population-based study. Am. J. Mens Health 15, 15579883211057990 (2021).

Johnson JR, W.-B. L., Hooker, S. E. Jr, Batai, K. & Kittles, R. A. Genetic contributions to prostate cancer disparities in men of West African descent. Front Oncol. 11, 770500 (2021).

Sartor, O. et al. Survival of African-American and Caucasian men after sipuleucel-T immunotherapy: outcomes from the PROCEED registry. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 23, 517–526 (2020).

Halabi, S. et al. Overall survival of Black and White men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 403–410 (2019).

George, D. J. et al. A prospective trial of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in Black and White men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer 127, 2954–2965 (2021).

Woods-Burnham, L., Johson, J. R., Hooker, S. E., Bedell, F. W., Dorff, T. B. & Kittles, R. A. The role of diverse populations in U.S. clinical trials. Med 2, 21–24 (2021).

Murthy, V. H., Krumholz, H. M. & Gross, C. P. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA 291, 2720–2726 (2004).

Lewis, D. D. & Cropp, C. D. The impact of African ancestry on prostate cancer disparities in the era of precision medicine. Genes 11, 1471 (2020).

Hooker, S. E. et al. Genetic ancestry analysis reveals misclassification of commonly used cancer cell lines. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 28, 1003 (2019).

DeSantis, C. E. et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 290–308 (2016).

Rathore, S. S. & Krumholz, H. M. Race, ethnic group, and clinical research. Bmj 327, 763–764 (2003).

Woods-Burnham, L. Not all champions are allies in health disparities research. Cell 183, 580–582 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Morehouse School of Medicine and the Division of Health Equities at City Hope for support. J.R.J. acknowledges the support received from NIH/NCI: U54CA118638 and NIH/NIMHD 2U54MD007602-36. L.W.-B. is grateful for the support received from 1T32CA186895, the Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator award (20YOUN04), the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program Early Investigator award (W81XWH2110038), and the NIH KL2TR002381.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R.J., N.M., L.W.-B., M.W., D.L. and B.R. researched data for the article. J.R.J., N.M., L.W.-B., M.W., D.L. and B.R. wrote the article. J.R.J., N.M., L.W.-B., M.W., D.L. and B.R. substantially contributed to the discussion of content. J.R.J., N.M., L.W.-B., D.L., S.E.H., D.G., B.R. and R.A.K. reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Urology thanks Quoc-Dien Trinh, Mack Roach and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, J.R., Mavingire, N., Woods-Burnham, L. et al. The complex interplay of modifiable risk factors affecting prostate cancer disparities in African American men. Nat Rev Urol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-023-00849-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-023-00849-5