Abstract

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) translate evidence into recommendations to improve patient care and outcomes. To provide an overview of schizophrenia CPGs, we conducted a systematic literature review of English-language CPGs and synthesized current recommendations for the acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics. Searches for schizophrenia CPGs were conducted in MEDLINE/Embase from 1/1/2004–12/19/2019 and in guideline websites until 06/01/2020. Of 19 CPGs, 17 (89.5%) commented on first-episode schizophrenia (FES), with all recommending antipsychotic monotherapy, but without agreement on preferred antipsychotic. Of 18 CPGs commenting on maintenance therapy, 10 (55.6%) made no recommendations on the appropriate maximum duration of maintenance therapy, noting instead individualization of care. Eighteen (94.7%) CPGs commented on long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs), mainly in cases of nonadherence (77.8%), maintenance care (72.2%), or patient preference (66.7%), with 5 (27.8%) CPGs recommending LAIs for FES. For treatment-resistant schizophrenia, 15/15 CPGs recommended clozapine. Only 7/19 (38.8%) CPGs included a treatment algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is an often debilitating, chronic, and relapsing mental disorder with complex symptomology that manifests as a combination of positive, negative, and/or cognitive features1,2,3. Standard management of schizophrenia includes the use of antipsychotic medications to help control acute psychotic episodes4 and prevent relapses5,6, whereas maintenance therapy is used in the long term after patients have been stabilized7,8,9. Two main classes of drugs—first- and second-generation antipsychotics (FGA and SGA)—are used to treat schizophrenia10. SGAs are favored due to the lower rates of adverse effects, such as extrapyramidal effects, tardive dyskinesia, and relapse11. However, pharmacologic treatment for schizophrenia is complicated because nonadherence is prevalent, and is a major risk factor for relapse9 and poor overall outcomes12. The use of long-acting injectable (LAI) versions of antipsychotics aims to limit nonadherence-related relapses and poor outcomes13.

Patient treatment pathways and treatment choices are determined based on illness acuity/severity, past treatment response and tolerability, as well as balancing medication efficacy and adverse effect profiles in the context of patient preferences and adherence patterns14,15. Clinical practice guidelines (CPG) serve to inform clinicians with recommendations that reflect current evidence from meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), individual RCTs and, less so, epidemiologic studies, as well as clinical experience, with the goal of providing a framework and road-map for treatment decisions that will improve quality of care and achieve better patients outcomes. The use of clinical algorithms or other decision trees in CPGs may improve the ease of implementation of the evidence in clinical practice16. While CPGs are an important tool for mental health professionals, they have not been updated on a regular basis like they have been in other areas of medicine, such as in oncology. In the absence of current information, other governing bodies, healthcare systems, and hospitals have developed their own CPGs regarding the treatment of schizophrenia, and many of these have been recently updated17,18,19. As such, it is important to assess the latest guidelines to be aware of the changes resulting from consideration of updated evidence that informed the treatment recommendations. Since CPGs are comprehensive and include the diagnosis as well as the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of individuals with schizophrenia, a detailed comparative review of all aspects of CPGs for schizophrenia would have been too broad a review topic. Further, despite ongoing efforts to broaden the pharmacologic tools for the treatment of schizophrenia20, antipsychotics remain the cornerstone of schizophrenia management8,21. Therefore, a focused review of guideline recommendations for the management of schizophrenia with antipsychotics would serve to provide clinicians with relevant information for treatment decisions.

To provide an updated overview of United States (US) national and English language international guidelines for the management of schizophrenia, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify CPGs and synthesize current recommendations for pharmacological management with antipsychotics in the acute and maintenance phases of schizophrenia.

Results

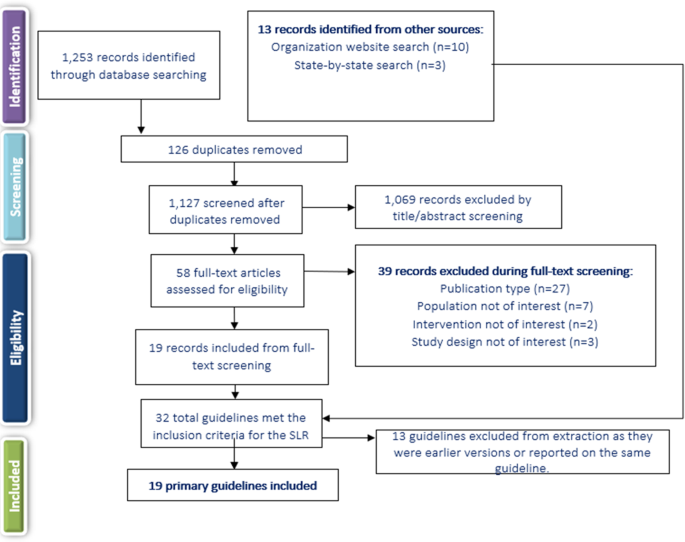

Systematic searches for the SLR yielded 1253 hits from the electronic literature databases. After removal of duplicate references, 1127 individual articles were screened at the title and abstract level. Of these, 58 publications were deemed eligible for screening at the full-text level, from which 19 were ultimately included in the SLR. Website searches of relevant organizations yielded 10 additional records, and an additional three records were identified by the state-by-state searches. Altogether, this process resulted in 32 records identified for inclusion in the SLR. Of the 32 sources, 19 primary CPGs, published/issued between 2004 and 2020, were selected for extraction, as illustrated in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1). While the most recent APA guideline was identified and available for download in 2020, the reference to cite in the document indicates a publication date of 2021.

Of the 19 included CPGs (Table 1), three had an international focus (from the following organizations: International College of Neuropsychopharmacology [CINP]22, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR]23, and World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry [WFSBP]24,25,26); seven originated from the US;17,18,19,27,28,29,30,31,32 three were from the United Kingdom (British Association for Psychopharmacology [BAP]33, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]34, and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN]35); and one guideline each was from Singapore36, the Polish Psychiatric Association (PPA)37,38, the Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA)14, the Royal Australia/New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP)39, the Association Française de Psychiatrie Biologique et de Neuropsychopharmacologie (AFPBN) from France40, and Italy41. Fourteen CPGs (74%) recommended treatment with specific antipsychotics and 18 (95%) included recommendations for the use of LAIs, while just seven included a treatment algorithm Table 2). The AGREE II assessment resulted in the highest score across the CPGs domains for NICE34 followed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines17. The CPA14, BAP33, and SIGN35 CPGs also scored well across domains.

Acute therapy

Seventeen CPGs (89.5%) provided treatment recommendations for patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode14,17,18,19,22,23,24,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39,40,41, but the depth and focus of the information varied greatly (Supplementary Table 1). In some CPGs, information on treatment of a first schizophrenia episode was limited or grouped with information on treating any acute episode, such as in the CPGs from CINP22, AFPBN40, New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services (NJDMHS)32, the APA17, and the PPA37,38, while the others provided more detailed information specific to patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode14,18,19,23,24,28,33,34,35,36,39,41. The American Association of Community Psychiatrists (AACP) Clinical Tips did not provide any information on the treatment of schizophrenia patients with a first episode29.

There was little agreement among CPGs regarding the preferred antipsychotic for a first schizophrenia episode. However, there was strong consensus on antipsychotic monotherapy and that lower doses are generally recommended due to better treatment response and greater adverse effect sensitivity. Some guidelines recommended SGAs over FGAs when treating a first-episode schizophrenia patient (RANZCP39, Texas Medication Algorithm Project [TMAP]28, Oregon Health Authority19), one recommended starting patients on an FGA (UNHCR23), and others stated specifically that there was no evidence of any difference in efficacy between FGAs and SGAs (WFSBP24, CPA14, SIGN35, APA17, Singapore guidelines36), or did not make any recommendation (CINP22, Italian guidelines41, NICE34, NJDMHS32, Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team [PORT]30,31). The BAP33 and WFBSP24 noted that while there was probably no difference between FGAs and SGAs in efficacy, some SGAs (olanzapine, amisulpride, and risperidone) may perform better than some FGAs. The Schizophrenia PORT recommendations noted that while there seemed to be no differences between SGAs and FGAs in short-term studies (≤12 weeks), longer studies (one to two years) suggested that SGAs may provide benefits in terms of longer times to relapse and discontinuation rates30,31. The AFPBN guidelines40 and Florida Medicaid Program guidelines18, which both focus on use of LAI antipsychotics, both recommended an SGA-LAI for patients experiencing a first schizophrenia episode. A caveat in most CPGs was that physicians and their patients should discuss decisions about the choice of antipsychotic and that the choice should consider individual patient factors/preferences, risk of adverse and metabolic effects, and symptom patterns17,18,19,22,24,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39,41.

Most CPGs recommended switching to a different monotherapy if the initial antipsychotic was not effective or not well tolerated after an adequate antipsychotic trial at an appropriate dose14,17,18,19,22,23,24,28,32,33,35,36,39. For patients initially treated with an FGA, the UNHCR recommended switching to an SGA (olanzapine or risperidone)23. Guidance on response to treatment varied in the measures used but typically required at least a 20% improvement in symptoms (i.e. reduction in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale or Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores) from pre-treatment levels.

Several CPGs contained recommendations on the duration of antipsychotic therapy after a first schizophrenia episode. The NJDMHS guidelines32 recommended nine to 12 months; CINP22 recommended at least one year; CPA14 recommended at least 18 months; WFSBP25, the Italian guidelines41, and NICE34 recommended 1 to 2 years; and the RANZCP39, BAP33, and SIGN35 recommended at least 2 years. The APA17 and TMAP28 recommended continuing antipsychotic treatment after resolution of first-episode symptoms but did not recommend a specific length of therapy.

Twelve guidelines14,18,22,24,28,30,31,33,34,35,36,39,40 (63.2%) discussed the treatment of subsequent/multiple episodes of schizophrenia (i.e., following relapse). These CPGs noted that the considerations guiding the choice of antipsychotic for subsequent/multiple episodes were similar to those for a first episode, factoring in prior patient treatment response, adverse effect patterns and adherence. The CPGs also noted that response to treatment may be lower and require higher doses to achieve a response than for first-episode schizophrenia, that a different antipsychotic than used to treat the first episode may be needed, and that a switch to an LAI is an option.

Several CPGs provided recommendations for patients with specific clinical features (Supplementary Table 1). The most frequently discussed group of clinical features was negative symptoms, with recommendations provided in the CINP22, UNHCR23, WFSBP24, AFPBN40, SIGN35, BAP33, APA17, and NJDMHS guidelines;32 negative symptoms were the sole focus of the guidelines from the PPA37,38. The guidelines noted that due to limited evidence in patients with predominantly negative symptoms, there was no clear benefit for any strategy, but that options included SGAs (especially amisulpride) rather than FGAs (WFSBP24, CINP22, AFPBN40, SIGN35, NJDMHS32, PPA37,38), and addition of an antidepressant (WFSBP24, UNHCR23, SIGN35, NJDMHS32) or lamotrigine (SIGN35), or switching to another SGA (NJDMHS32) or clozapine (NJDMHS32). The PPA guidelines37,38 stated that the use of clozapine or adding an antidepressant or other medication class was not supported by evidence, but recommended the SGA cariprazine for patients with predominant and persistent negative symptoms, and other SGAs for those with full-spectrum negative symptoms. However, the BAP33 stated that no recommendations can be made for any of these strategies because of the quality and paucity of the available evidence.

Some of the CPGs also discussed treatment of other clinical features to a limited degree, including depressive symptoms (CINP22, UNHCR23, CPA14, APA17, and NJDMHS32), cognitive dysfunction (CINP22, UNHCR23, WFSBP24, AFPBN40, SIGN35, BAP33, and NJDMHS32), persistent aggression (CINP22, WFSBP24, CPA14, AFPBN40, NICE34, SIGN35, BAP33, and NJDMHS32), and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (CINP22, RANZCP39, BAP33, APA17, and NJDMHS32).

Fifteen CPGs (78.9%) discussed treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS); all defined it as persistent, predominantly positive symptoms after two adequate antipsychotic trials; clozapine was the unanimous first choice14,17,18,19,22,23,24,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39. However, the UNHCR guidelines23, which included recommendations for treatment of refugees, noted that clozapine is only a reasonable choice in regions where white blood cell monitoring and specialist supervision are available, otherwise, risperidone or olanzapine are alternatives if they had not been used in the previous treatment regimen.

There were few options for patients who are resistant to clozapine therapy, and evidence supporting these options was limited. The CPA guidelines14 therefore stated that no recommendation can be given due to inadequate evidence. Other CPGs discussed options (but noted there was limited supporting evidence), such as switching to olanzapine or risperidone (WFSBP24, TMAP28), adding a second antipsychotic to clozapine (CINP22, NICE34, TMAP28, BAP33, Florida Medicaid Program18, Oregon Health Authority19, RANZCP39), adding lamotrigine or topiramate to clozapine (CINP22, Florida Medicaid Program18), combination therapy with two non-clozapine antipsychotics (Florida Medicaid Program18, NJDMHS32), and high-dose non-clozapine antipsychotic therapy (BAP33, SIGN35). Electroconvulsive therapy was noted as a last resort for patients who did not respond to any pharmacologic therapy, including clozapine, by 10 CPGs17,18,19,22,24,28,32,35,36,39.

Maintenance therapy

Fifteen CPGs (78.9%) discussed maintenance therapy to various degrees via dedicated sections or statements, while three others referred only to maintenance doses by antipsychotic agent18,23,29 without accompanying recommendations (Supplementary Table 2). Only the Italian guideline provided no reference or comments on maintenance treatment. The CINP22, WFSBP25, RANZCP39, and Schizophrenia PORT30,31 recommended keeping patients on the same antipsychotic and at the same dose on which they had achieved remission. Several CPGs recommended maintenance therapy at the lowest effective dose (NJDMHS32, APA17, Singapore guidelines36, and TMAP28). The CPA14 and SIGN35 defined the lower dose as 300–400 mg chlorpromazine equivalents or 4–6 mg risperidone equivalents, and the Singapore guidelines36 stated that the lower dose should not be less than half the original dose. TMAP28 stated that given the relapsing nature of schizophrenia, the maintenance dose should often be close to the original dose. While SIGN35 recommended that patients remain on the same antipsychotic that provided remission, these guidelines also stated that maintenance with amisulpride, olanzapine, or risperidone was preferred, and that chlorpromazine and other low-potency FGAs were also suitable. The BAP33 recommended that the current regimen be optimized before any dose reduction or switch to another antipsychotic occurs. Several CPGs recommended LAIs as an option for maintenance therapy (see next section).

Altogether, 10/18 (55.5%) CPGs made no recommendations on the appropriate duration of maintenance therapy, noting instead that each patient should be considered individually. Other CPGs made specific recommendations: Both the Both BAP33 and SIGN35 guidelines suggested a minimum of 2 years, the NJDMHS guidelines32 recommended 2–3 years; the WFSBP25 recommended 2–5 years for patients who have had one relapse and more than 5 years for those who have had multiple relapses; the RANZCP39 and the CPA14 recommended 2–5 years; and the CINP22 recommended that maintenance therapy last at least 6 years for patients who have had multiple episodes. The TMAP was the only CPG to recommend that maintenance therapy be continued indefinitely28.

Recommendations on the use of LAIs

All CPGs except the one from Italy (94.7%) discussed the use of LAIs for patients with schizophrenia to some extent. As shown in Table 3, among the 18 CPGs, LAIs were primarily recommended in 14 CPGs (77.8%) for patients who are non-adherent to other antipsychotic administration routes (CINP22, UNHCR23, RANZCP39, PPA37,38, Singapore guidelines36, NICE34, SIGN35, BAP33, APA17, TMAP28, NJDMHS32, AACP29, Oregon Health Authority19, Florida Medicaid Program18). Twelve CPGs (66.7%) also noted that LAIs should be prescribed based on patient preference (RANZCP39, CPA14, AFPBN40, Singapore guidelines36, NICE34, SIGN35, BAP33, APA17, Schizophrenia PORT30,31, AACP29, Oregon Health Authority19, Florida Medicaid Program18).

Thirteen CPGs (72.2%) recommended LAIs as maintenance therapy18,19,24,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39,40. While five CPGs (27.8%), i.e., AFPBN40, RANZCP39, TMAP28, NJDMHS32, and the Florida Medicaid Program18 recommended LAIs specifically for patients experiencing a first episode. While the CPA14 did not make any recommendations regarding when LAIs should be used, they discussed recent evidence supporting their use earlier in treatment. Five guidelines (27.8%, i.e., Singapore36, NICE34, SIGN35, BAP33, and Schizophrenia PORT30,31) noted that evidence around LAIs was not sufficient to support recommending their use for first-episode patients. The AFPBN guidelines40 also stated that LAIs (SGAs as first-line and FGAs as second-line treatment) should be more frequently considered for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Four CPGs (22.2%, i.e., CINP22, UNHCR23, Italian guidelines41, PPA guidelines37,38) did not specify when LAIs should be used. The AACP guidelines29, which evaluated only LAIs, recommended expanding their use beyond treatment for nonadherence, suggesting that LAIs may offer a more convenient mode of administration or potentially address other clinical and social challenges, as well as provide more consistent plasma levels.

Treatment algorithms

Only Seven CPGs (36.8%) included an algorithm as part of the treatment recommendations. These included decision trees or flow diagrams that map out initial therapy, durations for assessing response, and treatment options in cases of non-response. However, none of these guidelines defined how to measure response, a theme that also extended to guidelines that did not include treatment algorithms. Four of the seven guidelines with algorithms recommended specific antipsychotic agents, while the remaining three referred only to the antipsychotic class.

LAIs were not consistently incorporated in treatment algorithms and in six CPGs were treated as a separate category of medicine reserved for patients with adherence issues or a preference for the route of administration. The only exception was the Florida Medicaid Program18, which recommended offering LAIs after oral antipsychotic stabilization even to patients who are at that point adherent to oral antipsychotics.

Benefits and harms

The need to balance the efficacy and safety of antipsychotics was mentioned by all CPGs as a basic treatment paradigm.

Ten CPGs provided conclusions on benefits of antipsychotic therapy. The APA17 and the BAP33 guidelines stated that antipsychotic treatment can improve the positive and negative symptoms of psychosis and leads to remission of symptoms. These CPGs17,33 as well as those from NICE34 and CPA14 stated that these treatment effects can also lead to improvements in quality of life (including quality-adjusted life years), improved functioning, and reduction in disability. The CPA14 and APA17 guidelines noted decreases in hospitalizations with antipsychotic therapy, and the APA guidelines17 stated that long-term antipsychotic treatment can also reduce mortality. The UNHCR23 and the Italian41 guidelines noted that early intervention increased positive outcomes. The WFSBP24, AFPBN40, CPA14, BAP33, APA17, and NJDMHS32 affirmed that relapse prevention is a benefit of continued/maintenance treatment.

Some CPGs (WFSBP24, Italian41, CPA14, and SIGN35) noted that reduced risk for extrapyramidal adverse effects and treatment discontinuation were potential benefits of SGAs vs. FGAs.

The risk of adverse effects (e.g., extrapyramidal, metabolic, cardiovascular, and hormonal adverse effects, sedation, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome) was noted by all CPGs as the major potential harm of antipsychotic therapy14,17,18,19,22,23,24,28,29,30,31,32,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42. These adverse effects are known to limit long-term treatment and adherence24.

Discussion

This SLR of CPGs for the treatment of schizophrenia yielded 19 most updated versions of individual CPGs, published/issued between 2004 and 2020. Structuring our comparative review according to illness phase, antipsychotic type and formulation, response to antipsychotic treatment as well as benefits and harms, several areas of consistent recommendations emerged from this review (e.g., balancing risk and benefits of antipsychotics, preferring antipsychotic monotherapy; using clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia). On the other hand, other recommendations regarding other areas of antipsychotic treatment were mostly consistent (e.g., maintenance antipsychotic treatment for some time), somewhat inconsistent (e.g., differences in the management of first- vs multi-episode patients, type of antipsychotic, dose of antipsychotic maintenance treatment), or even contradictory (e.g., role of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia patients).

Consistent with RCT evidence43,44, antipsychotic monotherapy was the treatment of choice for patients with first-episode schizophrenia in all CPGs, and all guidelines stated that a different single antipsychotic should be tried if the first is ineffective or intolerable. Recommendations were similar for multi-episode patients, but factored in prior patient treatment response, adverse effect patterns, and adherence. There was also broad consensus that the side-effect profile of antipsychotics is the most important consideration when making a decision on pharmacologic treatment, also reflecting meta-analytic evidence4,5,10. The risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (especially with FGAs) and metabolic effects (especially with SGAs) were noted as key considerations, which are also reflected in the literature as relevant concerns4,45,46, including for quality of life and treatment nonadherence47,48,49,50.

Largely consistent with the comparative meta-analytic evidence regarding the acute4,51,52 and maintenance antipsychotic treatment5 effects of schizophrenia, the majority of CPGs stated there was no difference in efficacy between SGAs and FGAs (WFSBP24, CPA14, SIGN35, APA17, and Singapore guidelines36), or did not make any recommendations (CINP22, Italian guidelines41, NICE34, NJDMHS32, and Schizophrenia PORT30,31); three CPGs (BAP33, WFBSP24, and Schizophrenia PORT30,31) noted that SGAs may perform better than FGAs over the long term, consistent with a meta-analysis on this topic53.

The 12 CPGs that discussed treatment of subsequent/multiple episodes generally agreed on the factors guiding the choices of an antipsychotic, including that the decision may be more complicated and response may be lower than with a first episode, as described before7,54,55,56.

There was little consensus regarding maintenance therapy. Some CPGs recommended the same antipsychotic and dose that achieved remission (CINP22, WFSBP25, RANZCP39, and Schizophrenia PORT30,31) and others recommended the lowest effective dose (NJDMHS32, APA17, Singapore guidelines36, TMAP28, CPA14, and SIGN35). This inconsistency is likely based on insufficient data as well as conflicting results in existing meta-analyses on this topic57,58,59.

The 15 CPGs that discussed TRS all used the same definition for this condition, consistent with recent commendations60, and agreed that clozapine is the primary evidence-based treatment choice14,17,18,19,22,23,24,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39, reflecting the evidence base61,62,63. These CPGs also agreed that there are few options well supported by evidence for patients who do not respond to clozapine, with a recent meta-analysis of RCTs showing that electroconvulsive therapy augmentation may be the most evidence-based treatment option64.

One key gap in the treatment recommendations was how long patients should remain on antipsychotic therapy after a first episode or during maintenance therapy. While nine of the 17 CPGs discussing treatment of a first episode provided a recommended timeframe (varying from 1 to 2 years)14,22,24,32,33,34,35,39,41, the APA17 and TMAP28 recommended continuing antipsychotic treatment after resolution of first-episode symptoms but did not recommend a specific length of therapy. Similarly, six of the 18 CPGs discussing maintenance treatment recommended a specific duration of therapy (ranging from two to six years)14,22,25,32,39, while as many as 10 CPGs did not point to a firm end of the maintenance treatment, instead recommending individualized decisions. The CPGs not stating a definite endpoint or period of maintenance treatment after repeated schizophrenia episodes or even after a first episode of schizophrenia, reflects the different evidence types on which the recommendation is based. The RCT evidence ends after several years of maintenance treatment vs. discontinuation supporting ongoing antipsychotic treatment; however, naturalistic database studies do not indicate any time period after which one can safely discontinue maintenance antipsychotic care, even after a first schizophrenia episode8,65. In fact, stopping antipsychotics is associated not only with a substantially increased risk of hospitalization but also mortality65,66,67. In this sense, not stating an endpoint for antipsychotic maintenance therapy should not be taken as an implicit statement that antipsychotics should be discontinued at any time; data suggest the contrary.

A further gap exists regarding the most appropriate treatment of negative symptoms, such as anhedonia, amotivation, asociality, affective flattening, and alogia1, a long-standing challenge in the management of patients with schizophrenia. Negative symptoms often persist in patients after positive symptoms have resolved, or are the presenting feature in a substantial minority of patients22,35. Negative symptoms can also be secondary to pharmacotherapy22,68. Antipsychotics have been most successful in treating positive symptoms, and while eight of the CPGs provided some information on treatment of negative symptoms, the recommendations were generally limited17,22,23,24,32,33,35,40. Negative symptom management was a focus of the PPA guidelines, but the guidelines acknowledged that supporting evidence was limited, often due to the low number of patients with predominantly negative symptoms in clinical trials37,38. The Polish guidelines are also one of the more recently developed and included the newer antipsychotic cariprazine as a first-line option, which although being a point of differentiation from the other guidelines, this recommendation was based on RCT data69.

Another area in which more direction is needed is on the use of LAIs. While all but one of the 19 CPGs discussed this topic, the extent of information and recommendations for LAI use varied considerably. All CPGs categorized LAIs as an option to improve adherence to therapy or based on patient preference. However, 5/18 CPGs (27.8%) recommended the use of LAI early in treatment (at first episode: AFPBN40, RANZCP39, TMAP28, NJDMHS32, and Florida Medicaid Program18) or across the entire illness course, while five others stated there was not sufficient evidence to recommend LAIs for these patients (Singapore36, NICE34, SIGN35, BAP33, and Schizophrenia PORT30,31). The role of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia was the only point where opposing recommendations were found across CPGs. This contradictory stance was not due to the incorporation of newer data suggesting benefits of LAIs in first episode and early-phase patients with schizophrenia70,71,72,73,74 in the CPGs recommending LAI use in first-episode patients, as CPGs recommending LAI use were published between 2005 and 2020, while those opposing LAI use were published between 2011 and 2020. Only the Florida Medicaid CPG recommended LAIs as a first step equivalent to oral antipsychotics (OAP) after initial OAP response and tolerability, independent of nonadherence or other clinical variables. This guideline was also the only CPG to fully integrate LAI use in their clinical algorithm. The remaining six CPGs that included decision tress or treatment algorithms regarded LAIs as a separate paradigm of treatment reserved for nonadherence or patients preference rather than a routine treatment option to consider. While some CPGs provided fairly detailed information on the use of LAIs (AFPBN40, AACP29, Oregon Health Authority19, and Florida Medicaid Program18), others mentioned them only in the context of adherence issues or patient preference. Notably, definitions of and means to determine nonadherence were not reported. One reason for this wide range of recommendations regarding the placement of LAIs in the treatment algorithm and clinical situations that prompt LAI use might be due to the fact that CPGs generally favor RCT evidence over evidence from other study designs. In the case of LAIs, there was a notable dissociation between consistent meta-analytic evidence of statistically significant superiority of LAIs vs OAPs in mirror-image75 and cohort study designs76 and non-significant advantages in RCTs77. Although patients in RCTs comparing LAIs vs OAPs were less severely ill and more adherent to OAPs77 than in clinical care and although mirror-image and cohort studies arguably have greater external validity than RCTs78, CPGs generally disregard evidence from other study designs when RCT evidence exits. This narrow focus can lead to disregarding important additional data. Nevertheless, a most updated meta-analysis of all 3 study designs comparing LAIs with OAPs demonstrated consistent superiority of LAIs vs OAPs for hospitalization or relapse across all 3 designs79, which should lead to more uniform recommendations across CPGs in the future.

Only seven CPGs included treatment algorithms or flow charts to guide LAI treatment selection for patients with schizophrenia17,18,19,24,29,35,40. However, there was little commonality across algorithms beyond the guidance on LAIs mentioned above, as some listed specific treatments and conditions for antipsychotic switches, while others indicated that medication choice should be based on a patient’s preferences and responses, side effects, and in some cases, cost effectiveness. Since algorithms and flow charts facilitate the reception, adoption and implementation of guidelines, future CPGs should include them as dissemination tools, but they need to reflect the data and detailed text and be sufficiently specific to be actionable.

The systematic nature in the identification, summarization, and assessment of the CPGs is a strength of this review. This process removed any potential bias associated with subjective selection of evidence, which is not reproducible. However, only CPGs published in English were included and regardless of their quality and differing timeframes of development and publication, complicating a direct comparison of consensus and disagreement. Finally, based on the focus of this SLR, we only reviewed pharmacologic management with antipsychotics. Clearly, the assessment, other pharmacologic and, especially, psychosocial interventions are important in the management of individuals with schizophrenia, but these topics that were covered to varying degrees by the evaluated CPGs were outside of the scope of this review.

Numerous guidelines have recently updated their recommendations on the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia, which we have summarized in this review. Consistent recommendations were observed across CPGs in the areas of balancing risk and benefits of antipsychotics when selecting treatment, a preference for antipsychotic monotherapy, especially for patients with a first episode of schizophrenia, and the use of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. By contrast, there were inconsistencies with regards to recommendations on maintenance antipsychotic treatment, with differences existing on type and dose of antipsychotic, as well as the duration of therapy. However, LAIs were consistently recommended, but mainly suggested in cases of nonadherence or patient preference, despite their established efficacy in broader patient populations and clinical scenarios in clinical trials. Guidelines were sometimes contradictory, with some recommending LAI use earlier in the disease course (e.g., first episode) and others suggesting they only be reserved for later in the disease. This inconsistency was not due to lack of evidence on the efficacy of LAIs in first-episode schizophrenia or the timing of the CPG, so that other reasons might be responsible, including possibly bias and stigma associated with this route of treatment administration. Lastly, gaps existed in the guidelines for recommendations on the duration of maintenance treatment, treatment of negative symptoms, and the development/use of treatment algorithms whenever evidence is sufficient to provide a simplified summary of the data and indicate their relevance for clinical decision making, all of which should be considered in future guideline development/revisions.

Methods

The SLR followed established best methods used in systematic review research to identify and assess the available CPGs for pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotics in the acute and maintenance phases80,81. The SLR was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, including use of a prespecified protocol to outline methods for conducting the review. The protocol for this review was approved by all authors prior to implementation but was not submitted to an external registry.

Data sources and search algorithms

Searches were conducted by two independent investigators in the MEDLINE and Embase databases via OvidSP to identify CPGs published in English. Articles were identified using search algorithms that paired terms for schizophrenia with keywords for CPGs. Articles indexed as case reports, reviews, letters, or news were excluded from the searches. The database search was limited to CPGs published from January 1, 2004, through December 19, 2019, without limit to geographic location. In addition to the database sources, guideline body websites and state-level health departments from the US were also searched for relevant CPGs published through June 2020. A manual check of the references of recent (i.e., published in the past three years), relevant SLRs and relevant practice CPGs was conducted to supplement the above searches and ensure and the most complete CPG retrieval.

Ethics

This study did not involve human subjects as only published evidence was included in the review; ethical approval from an institution was therefore not required.

Selection of CPGs for inclusion

Each title and abstract identified from the database searches was screened and selected for inclusion or exclusion in the SLR by two independent investigators based on the populations, interventions/comparators, outcomes, study design, time period, language, and geographic criteria shown in Table 4. During both rounds of the screening process, discrepancies between the two independent reviewers were resolved through discussion, and a third investigator resolved any disagreement. Articles/documents identified by the manual search of organizational websites were screened using the same criteria. All accepted studies were required to meet all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Only the most recent version of organizational CPGs was included for data extraction.

Data extraction and synthesis

Information on the recommendations regarding the antipsychotic management in the acute and maintenance phases of schizophrenia and related benefits and harms was captured from the included CPGs. Each guideline was reviewed and extracted by a single researcher and the data were validated by a senior team member to ensure accuracy and completeness. Additionally, each included CPG was assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool. Following extraction and validation, results were qualitatively summarized across CPGs.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of the SLR are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Correll, C. U. & Schooler, N. R. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16, 519–534 (2020).

Kahn, R. S. et al. Schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1, 15067 (2015).

Millan, M. J. et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: progress and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 485–515 (2016).

Huhn, M. et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 394, 939–951 (2019).

Kishimoto, T., Hagi, K., Nitta, M., Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Long-term effectiveness of oral second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct head-to-head comparisons. World Psychiatry 18, 208–224 (2019).

Leucht, S. et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379, 2063–2071 (2012).

Carbon, M. & Correll, C. U. Clinical predictors of therapeutic response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 16, 505–524 (2014).

Correll, C. U., Rubio, J. M. & Kane, J. M. What is the risk-benefit ratio of long-term antipsychotic treatment in people with schizophrenia? World Psychiatry 17, 149–160 (2018).

Emsley, R., Chiliza, B., Asmal, L. & Harvey, B. H. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 13, 50 (2013).

Correll, C. U. & Kane, J. M. Ranking antipsychotics for efficacy and safety in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 225–226 (2020).

Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 12, 345–357 (2010).

Kane, J. M., Kishimoto, T. & Correll, C. U. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry 12, 216–226 (2013).

Correll, C. U. et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J. Clin. Psychiatry 77, 1–24 (2016).

Remington, G. et al. Guidelines for the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia in adults. Can. J. Psychiatry 62, 604–616 (2017).

American Psychiatric Association. Treatment recommendations for patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 1–56 (2004).

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Field, M. J., & Lohr, K. N. (Eds.). Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. (National Academies Press (US), 1990).

American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia, 3rd edn. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841.

Florida Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program. 2019–2020 Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults. (2020). Available at: https://floridabhcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2019-Psychotherapeutic-Medication-Guidelines-for-Adults-with-References_06-04-20.pdf.

Mental Health Clinical Advisory Group, Oregon Health Authority. Mental Health Care Guide for Licensed Practitioners and Mental Health Professionals. (2019). Available at: https://sharedsystems.dhsoha.state.or.us/DHSForms/Served/le7548.pdf.

Krogmann, A. et al. Keeping up with the therapeutic advances in schizophrenia: a review of novel and emerging pharmacological entities. CNS Spectr. 24, 38–69 (2019).

Fountoulakis, K. N. et al. The report of the joint WPA/CINP workgroup on the use and usefulness of antipsychotic medication in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001546 (2020).

Leucht, S. et al. CINP Schizophrenia Guidelines. (CINP, 2013). Available at: https://www.cinp.org/resources/Documents/CINP-schizophrenia-guideline-24.5.2013-A-C-method.pdf.

Ostuzzi, G. et al. Mapping the evidence on pharmacological interventions for non-affective psychosis in humanitarian non-specialised settings: A UNHCR clinical guidance. BMC Med. 15, 197 (2017).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 1: Update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 13, 318–378 (2012).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, Part 2: Update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 14, 2–44 (2013).

Hasan, A. et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia - a short version for primary care. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 21, 82–90 (2017).

Moore, T. A. et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2006 update. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 1751–1762 (2007).

Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP). Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Procedural Manual. (2008). Available at: https://jpshealthnet.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/tmapalgorithmforschizophrenia.pdf.

American Association of Community Psychiatrists (AACP). Clinical Tips Series, Long Acting Antipsychotic Medications. (2017). Accessed at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view.

Buchanan, R. W. et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr. Bull. 36, 71–93 (2010).

Kreyenbuhl, J. et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr. Bull. 36, 94–103 (2010).

New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services. Pharmacological Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Schizophrenia. (2005). Available at: https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dmhs_delete/consumer/NJDMHS_Pharmacological_Practice_Guidelines762005.pdf.

Barnes, T. R. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 34, 3–78 (2020).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. (2014). Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of Schizophrenia: A National Clinical Guideline. (2013). Available at: https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign131.pdf.

Verma, S. et al. Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Schizophrenia. Singap. Med. J. 52, 521–526 (2011).

Szulc, A. et al. Recommendations for the treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms. Standards of pharmacotherapy by the Polish Psychiatric Association (Polskie Towarzystwo Psychiatryczne), part 1. Rekomendacje dotyczace leczenia schizofrenii z. objawami negatywnymi. Stand. farmakoterapii Polskiego Tow. Psychiatrycznego, czesc 1. 53, 497–524 (2019).

Szulc, A. et al. Recommendations for the treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms. Standards of pharmacotherapy by the Polish Psychiatric Association (Polskie Towarzystwo Psychiatryczne), part 2. Rekomendacje dotyczace leczenia schizofrenii z. objawami negatywnymi. Stand. farmakoterapii Polskiego Tow. Psychiatrycznego, czesc 2. 53, 525–540 (2019).

Galletly, C. et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 50, 410–472 (2016).

Llorca, P. M. et al. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 13, 340 (2013).

De Masi, S. et al. The Italian guidelines for early intervention in schizophrenia: development and conclusions. Early Intervention Psychiatry 2, 291–302 (2008).

Barnes, T. R. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 25, 567–620 (2011).

Correll, C. U. et al. Efficacy of 42 pharmacologic cotreatment strategies added to antipsychotic monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic overview and quality appraisal of the meta-analytic evidence. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 675–684 (2017).

Galling, B. et al. Antipsychotic augmentation vs. monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. World Psychiatry 16, 77–89 (2017).

Pillinger, T. et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 64–77 (2020).

Rummel-Kluge, C. et al. Second-generation antipsychotic drugs and extrapyramidal side effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Schizophr. Bull. 38, 167–177 (2012).

Angermeyer, M. C. & Matschinger, H. Attitude of family to neuroleptics. Psychiatr. Prax. 26, 171–174 (1999).

Dibonaventura, M., Gabriel, S., Dupclay, L., Gupta, S. & Kim, E. A patient perspective of the impact of medication side effects on adherence: results of a cross-sectional nationwide survey of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 12, 20 (2012).

McIntyre, R. S. Understanding needs, interactions, treatment, and expectations among individuals affected by bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: the UNITE global survey. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70(Suppl 3), 5–11 (2009).

Tandon, R. et al. The impact on functioning of second-generation antipsychotic medication side effects for patients with schizophrenia: a worldwide, cross-sectional, web-based survey. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 19, 42 (2020).

Zhang, J. P. et al. Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16, 1205–1218 (2013).

Zhu, Y. et al. Antipsychotic drugs for the acute treatment of patients with a first episode of schizophrenia: a systematic review with pairwise and network meta-analyses. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 694–705 (2017).

Kishimoto, T. et al. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of second-generation antipsychotics versus first-generation antipsychotics. Mol. Psychiatry 18, 53–66 (2013).

Leucht, S. et al. Sixty years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 927–942 (2017).

Samara, M. T., Nikolakopoulou, A., Salanti, G. & Leucht, S. How many patients with schizophrenia do not respond to antipsychotic drugs in the short term? An analysis based on individual patient data from randomized controlled trials. Schizophr. Bull. 45, 639–646 (2019).

Zhu, Y. et al. How well do patients with a first episode of schizophrenia respond to antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 27, 835–844 (2017).

Bogers, J. P. A. M., Hambarian, G., Michiels, M., Vermeulen, J. & de Haan, L. Risk factors for psychotic relapse after dose reduction or discontinuation of antipsychotics in patients with chronic schizophrenia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. Open 46, Suppl 1 S326 (2020).

Tani, H. et al. Factors associated with successful antipsychotic dose reduction in schizophrenia: a systematic review of prospective clinical trials and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 887–901 (2020).

Uchida, H., Suzuki, T., Takeuchi, H., Arenovich, T. & Mamo, D. C. Low dose vs standard dose of antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 788–799 (2011).

Howes, O. D. et al. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: treatment response and resistance in psychosis (TRRIP) working group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 216–229 (2017).

Masuda, T., Misawa, F., Takase, M., Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Association with hospitalization and all-cause discontinuation among patients with schizophrenia on clozapine vs other oral second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 1052–1062 (2019).

Siskind, D., McCartney, L., Goldschlager, R. & Kisely, S. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 209, 385–392 (2016).

Siskind, D., Siskind, V. & Kisely, S. Clozapine response rates among people with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: data from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 62, 772–777 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. ECT augmentation of clozapine for clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Psychiatr. Res. 105, 23–32 (2018).

Tiihonen, J., Tanskanen, A. & Taipale, H. 20-year nationwide follow-up study on discontinuation of antipsychotic treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 765–773 (2018).

Taipale, H. et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 197, 274–280 (2018).

Taipale, H. et al. 20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry 19, 61–68 (2020).

Carbon, M. & Correll, C. U. Thinking and acting beyond the positive: the role of the cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 19(Suppl 1), 38–52 (2014).

Krause, M. et al. Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or prominent negative symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 268, 625–639 (2018).

Kane, J. M. et al. Effect of long-acting injectable antipsychotics vs usual care on time to first hospitalization in early-phase schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 1217–1224 (2020).

Schreiner, A. et al. Paliperidone palmitate versus oral antipsychotics in recently diagnosed schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 169, 393–399 (2015).

Subotnik, K. L. et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 822–829 (2015).

Tiihonen, J. et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 603–609 (2011).

Zhang, F. et al. Efficacy, safety, and impact on hospitalizations of paliperidone palmitate in recent-onset schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 11, 657–668 (2015).

Kishimoto, T., Nitta, M., Borenstein, M., Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74, 957–965 (2013).

Kishimoto, T. et al. Effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 603–619 (2018).

Kishimoto, T. et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 192–213 (2014).

Kane, J. M., Kishimoto, T. & Correll, C. U. Assessing the comparative effectiveness of long-acting injectable vs. oral antipsychotic medications in the prevention of relapse provides a case study in comparative effectiveness research in psychiatry. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 66, S37–41 (2013).

Kishimoto, T., Hagi, K., Kurokawa, S., Kane, J. M. & Correll, C. U. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry 8, 387–404 (2021).

Cook, D. J., Mulrow, C. D. & Haynes, R. B. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann. Intern. Med. 126, 376–380 (1997).

Higgins, J. P. T. & Green, S. Cochrane Collaboration Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. (The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008).

Acknowledgements

This study received financial funding from Janssen Scientific Affairs.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C., A.M., R.G., C.P., C.B., K.J., J.K.S., E.S. and E.K. contributed to the conception and the design of the study. A.M., R.G. and E.S. conducted the literature review, including screening, and extraction of the included guidelines. All authors contributed to the interpretations of the results for the review; A.M. and C.C. drafted the manuscript and all authors revised it critically for intellectual content. All authors gave their final approval of the completed manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.C. has received personal fees from Alkermes plc, Allergan plc, Angelini Pharma, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc, Janssen Pharmaceutica/Johnson & Johnson, LB Pharma International BV, H Lundbeck A/S, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Neurocrine Biosciences, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Inc, Pfizer, Inc, Recordati, Rovi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Axsome Therapeutics, Inc, Indivior, Merck & Co, Mylan NV, MedInCell, and Karuna Therapeutics and grants from Janssen Pharmaceutica, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Berlin Institute of Health, the National Institute of Mental Health, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the Thrasher Foundation outside the submitted work; receiving royalties from UpToDate; and holding stock options in LB Pharma. A.M., R.G., and E.S. were all employees of Evidera at the time the study was conducted on which the manuscript was based. C.P., C.B., K.J., J.K.S., and E.K. were all employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, who hold stock/shares, at the time the study was conducted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Correll, C.U., Martin, A., Patel, C. et al. Systematic literature review of schizophrenia clinical practice guidelines on acute and maintenance management with antipsychotics. Schizophr 8, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-021-00192-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-021-00192-x

This article is cited by

-

Psychosis superspectrum II: neurobiology, treatment, and implications

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Sex Differences Between Female and Male Individuals in Antipsychotic Efficacy and Adverse Effects in the Treatment of Schizophrenia

CNS Drugs (2024)

-

Antipsychotic Discontinuation through the Lens of Epistemic Injustice

Community Mental Health Journal (2024)

-

Delphi panel to obtain clinical consensus about using long-acting injectable antipsychotics to treat first-episode and early-phase schizophrenia: treatment goals and approaches to functional recovery

BMC Psychiatry (2023)

-

Machine learning methods to predict outcomes of pharmacological treatment in psychosis

Translational Psychiatry (2023)