Abstract

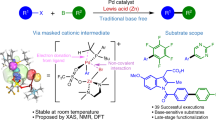

Metal-catalyzed cross-couplings provide powerful, concise, and accurate methods to construct carbon–carbon bonds from organohalides and organometallic reagents. Recent developments extended cross-couplings to reactions where one of the two partners connects with an aryl or alkyl carbon–hydrogen bond. From an economic and environmental point of view, oxidative couplings between two carbon–hydrogen bonds would be ideal. Oxidative coupling between phenyl and “inert” alkyl carbon–hydrogen bonds still awaits realization. It is very difficult to develop successful strategies for oxidative coupling of two carbon–hydrogen bonds owning different chemical properties. This article provides a solution to this challenge in a convenient preparation of dihydrobenzofurans from substituted phenyl alkyl ethers. For the phenyl carbon–hydrogen bond activation, our choice falls on the carboxylic acid fragment to form the palladacycle as a key intermediate. Through careful manipulation of an additional ligand, the second “inert” alkyl carbon–hydrogen bond activation takes place to facilitate the formation of structurally diversified dihydrobenzofurans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon–hydrogen bonds are ubiquitous in organic compounds. With fast developments in the field of C–H functionalization during the past three decades, the understanding of the reactivity of carbon–hydrogen bonds is continuously updated. Many transformations involving carbon–hydrogen bonds as at least one of the partners have been developed to construct carbon–carbon bonds1. For example, both aryl and alkyl carbon–hydrogen bonds take part in cross-couplings with aryl/alkyl halides2, 3. Vice versa, with or without directing groups, aryl carbon–hydrogen bonds play key roles as surrogates of aryl halides in couplings with various organometallic reagents under oxidative conditions4, 5. Arguably, however, the most efficient and ideal method to construct carbon–carbon bonds is to use carbon–hydrogen bonds exclusively as precursors in a single chemical operation.

Stimulated by this idea, the concept of cross-dehydrogenative coupling (CDC) was conceived and applied to construct different types of carbon–carbon bonds6. However, in most of these cases, one of the carbon–hydrogen bonds must exhibit extraordinary reactivity (for example, carbon–hydrogen bonds adjacent to heteroatoms, benzyl/allyl carbon–hydrogen bonds, as well as carbon–hydrogen bonds at α-position of a carbonyl group)7,8,9,10. Cross-couplings between two “inert” carbon–hydrogen bonds face a number of challenges: the requirement of high chemo- and regioselectivity in precursors containing multiple carbon–hydrogen bonds, the need to find conditions to activate two carbon–hydrogen bonds of different reactivities in a one-pot process, and the requirement to control cross-coupling between two partners over that of homocoupling.

Oxidative couplings between two aryl carbon–hydrogen bonds have been well developed in both intra- and intermolecular manner over the past years11,12,13. The next goal is to develop efficient oxidative coupling protocols to construct carbon–carbon bonds between both “inert” aromatic and aliphatic carbon–hydrogen bonds. Indeed, this would be the most straightforward method for the alkylation of aromatic compounds.

We hypothesized that benzo-fused ring systems may be accessible from substituted benzene with alkyl groups tethered with different linkers. Indeed, benzo-fused scaffolds playing important functions in life science and material chemistry, which can be constructed through intramolecular cross-couplings or reductive couplings from two functionalized motifs (Fig. 1a)14, 15. Recent advances in carbon–hydrogen activation provided efficient and competitive pathways to approach benzo-fused rings from monofunctionalized starting materials (Fig. 1b)2, 16. Obviously, the ideal intramolecular oxidative coupling from simple precursors would do away with a prefunctionalization as shown in Fig. 1c. Unfortunately, current chemistry, for example, via the direct carbon–hydrogen bond activation based on radical chemistry and directing strategy, has not been successful to reach this goal17, 18. To date, only two excellent examples have been reported for the intramolecular cross-coupling between sp 2 and sp 3 carbon–hydrogen bonds to construct fused rings. Both were initiated from electron-rich heterocylces19, 20. Examples with benzene derivatives are not literature-known. We aimed to meet this challenge through a demonstration of the synthesis of versatile dihydrobenzofuran derivatives from readily available and simple phenyl alkyl ethers.

As the directing strategy has proven efficient for single carbon–hydrogen bond activation21, 22 and the intramolecular aliphatic carbon–hydrogen bond activations have been shown effective from in-situ-generated Pd(II) complexes from an oxidative addition of aryl halides with Pd(0) catalysts23, we conceived that a new strategy for reaching our target may be through ligand-manipulated tandem carbon–hydrogen activations (Fig. 1d). Based on this design, a versatile directing group would facilitate the first aryl carbon–hydrogen activation to form a palladacycle. It is then essential that an external ligand enters to assist the generation of the key intermediate II through the second aliphatic carbon–hydrogen activation.

The carboxylate group has been shown to be a weak yet efficient coordinating group in numerous directed carbon–hydrogen transformations24,25,26. Upon ligand manipulation, the intermediate I provides Pd complex II, which may undergo strain release of the palladacycle and Pd insertion into the aliphatic carbon–hydrogen bond. Inspired by recent successes in the use of ligands to promote efficiency27, accelerate the rate28, and even control stereoselectivity in carbon–hydrogen activations29, 30, we envisaged that the judicious choice of a ligand may give access to the targeted catalytic oxidative coupling between phenyl- and “inert” alkyl carbon–hydrogen bonds.

Results

Oxidative coupling of sp 2 and sp 3 C–H bonds

Based on this design, ether 1a was readily synthesized from the commercial 3-hydroxy-6-methylbenzoic acid and isobutene. The aryl C(6) position, prone to be a competitive site for palladation, was blocked by a methyl group. Pd(OAc)2 was selected as the catalyst, which plays crucial roles in C–H activations. We evaluated various types of ligands to promote oxidative coupling (Supplementary Fig. 65)27,28,29. Finally, to our delight, we found that the addition of 1,4- benzoquinone and acridine led to success. To efficiently isolate the desired product, esterification with MeI was carried out and this provided ester 2a with 85% yield.

The tert-butyl ether function is structurally special and its derivatives are relatively difficult to synthesize. In addition, it can only deliver 2,2-dimethyl dihydydrobenzofuran derivatives in the present application, thereby highly limiting potential applications. We therefore sought to further expand this chemistry to secondary alkyl ethers, which can be readily produced from the secondary alcohols in a single step through either Buchwald–Hartwig etherification31 or SN2 substitution (for example, Mitsunobu reaction)32. We were pleased to find that the isopropyl ether 1b reacted smoothly to give 2b with 76% yield (Fig. 2). With this success, we tested a number of different secondary ethers with various chain lengths and found all of them to be successful substrates. The longer chains only slightly decreased yields (2c-2f). It is important to note that the second carbon–hydrogen activation only took place at the primary position, leaving the secondary carbon–hydrogen bond untouched. The oxidative coupling showed excellent compatibility of functionalities. Thus, C-F (2g), acetate (-OAc, 2h) and silyl ether (-OTIPS, 2i), and phthalidyl-protected amine (2j) functions are compatible. This bodes well for further product manipulation. Although in many transformations benzylic carbon–hydrogen bonds show better reactivity than Me, in our case, Me won over CH2Ph. Interestingly, oxidative couplings between two aryl carbon–hydrogen bonds were not observed under current conditions, perhaps indicating the second carbon–hydrogen activation to be mostly controlled by steric hindrance (2k).

Scope of phenyl alkyl ether substrates. Unless otherwise noted, the reaction conditions were as follows: 1 (0.3 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.03 mmol), 1,4-BQ (0.06 mmol), Ag2CO3 (0.6 mmol), Acridine (0.06 mmol), KH2PO4 (0.3 mmol), NaOAc (0.45 mmol), and tAmylOH (2.0 mL), 140 °C, 24 h. Then the solvent was removed, and MeI (1.5 mmol), K2CO3 (0.6 mmol), and DMF (3.0 mL) were added at 50 °C for 12 h. a15 mol% Pd(OAc)2; b20 mol% Pd(OAc)2; c4-Nitrobenzyl bromide (1.5 mmol) instead of MeI; dSelectivity was determined by crude 1H NMR spectroscopy

Unsubstituted and substituted phenyl groups could be attached to the side chain with a two-carbon linker. All of these substrates showed good reactivity to give the desired products (2l-2q), with unsubstituted phenyl group giving the best yield (2l, 77%). Increasing the catalyst loading, in most cases, gave better yield. Gratifyingly, transformable functionalities, including -OMe (2m), -F (2n), -Cl (2o), and -Br (2p), are suitable, providing further opportunities to make diversified libraries of dihydrobenzofurans. To confirm the formation of the dihydrobenzofuran scaffolds, the structure of 2ma (the hydrolysis product of 2m) was unambiguously confirmed by X-ray structure of its single crystal (Supplementary Fig. 66). Under the standard conditions, ethyl ether (2r) was also workable albeit in a low yield.

It is important to note that secondary carbon–hydrogen bonds could also react in the absence of primary carbon–hydrogen bonds. When cyclohexyl ether was subjected, the desired product 2s was isolated with an excellent distereoselectivity albeit in a relatively low yield. If two different methylene carbon–hydrogen bonds are present, the benzylic one showed dominant reactivity over the aliphatic secondary one (2t). However, in this case, both diastereoisomers were obtained in a nearly 1.5:1 ratio. These results provide another possibility to expand this chemistry to a wider substrate scope to form 2,3-disubstiuted dihydrobenzofuran derivatives.

We also tested the motive of different benzoic acids in ether. The ortho-aryl substituents were varied first. Other than methyl group, alkoxyl groups also showed good reactivity while the ortho- isopropoxyl group gave a much better yield (2v) than the ortho-ethoxyl group (2u). It is interesting to note that both ortho -F- and Cl- substituents led to successful reactions (2w and 2x). Not only do these results extend the substrate scope but also offer the possibility to functionalize the products. We additionally tested 3,5-disubstituted benzoic acids and observed oxidative coupling to proceed smoothly. When 3,5-di-tert-butoxybenzoic acid were submitted, dual oxidative couplings took place to afford tricyclic scaffolds in an excellent yield (2y).

Transformations of the dihydrobenzofuran scaffolds

In order to demonstrate the potential of applications of this method, we explored the transformations of the carboxylic acid/ester function in dihydrobenzofuran scaffolds (Fig. 3). Obviously, different esters (3 and 4) could be obtained using the phenylboronic acid or propargyl bromide. As benzofuran is an important scaffold with multiple bioreactivities, aromatization of 2b was conducted and benzofuran 5 was obtained in a good yield. This offers an alternative to syntheses of benzofuran derivatives33. Next, decarboxylation of the product took place smoothly34. Cross-coupling of the ortho-chloro substituent to give phenylated dihydrobenzofuran proceeded in excellent yield35. The carboxylic group could be transformed into an NH2 group (8) through Curtis rearrangement36. Last but not the least, with methyl substituents, further benzylic C–H activation and lactonization took place to produce a tricyclic compound (9) in a moderate yield37.

Diversified transformations to produce different substituted benzofurans and dihydrobenzofurans. a 2aa (the hydrolysis product of 2a, 0.2 mmol), PhB(OH)2 (0.4 mmol), Cu(OTf)2 (0.04 mmol), Ag2CO3 (2.0 equiv), DMSO (1.0 mL), 120 °C, 2 h, air, 3 was obtained as 67% yield. b 2ma (the hydrolysis product of 2m, 0.3 mmol), 3-Bromopropyne (1.5 mmol), K2CO3 (0.6 mmol), DMF (3.0 mL), 12 h, air, 4 was obtained as 98% yield. c 2b (0.3 mmol), DDQ (0.36 mmol), Toluene (3.0 mL), reflux, N2, 48 h, 5 was obtained as 74% yield. d 2aa (0.3 mmol), Cu2O (0.3 mmol), 1,10-Phen (0.6 mmol), NMP, 160 °C, 6 was obtained as 73% yield. e 2x (0.3 mmol), PhB(OH)2 (0.45 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.2 mol%), dicyclohexyl(2’,6’-dimethoxy-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2-yl)phosphane (0.5 mol%), K3PO4 (0.6 mmol), Toluene (2.0 mL), 100 °C, 12 h, N2, 7 was obtained as 86% yield. f (1) 2aa (0.3 mmol), DPPA (0.315 mmol), Et3N (0.9 mmol), THF (2.0 mL), 25 °C, 3 h; (2) H2O, reflux, overnight, 8 was obtained as 81% yield. g 2aa (0.2 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol%), Ac-Leu-OH (30 mol%), Ag2CO3 (0.6 mmol), K2HPO4 (0.5 mmol), 9 was obtained as 52% yield

Enantiopure dihydrobenzofurans are important as core structures of natural products and drug candidates. Efficient methods to approach single enantiomers of products are very important. Enantiopure secondary alcohols are easily produced, broadly commercially available, and methods for enantiomer inversion are well documented. With this background, we expanded the coupling protocol to the synthesis of a pair of stereoisomers of dihydrobenzofuran (R)/(S)-2i from the same enantiomerically pure secondary alcohol (S)-11. Through double Mitsunobu reactions, the configuration of stereogenic center was retained and (S)-2i was obtained in a good yield. By one step Mitsunobu reaction, the stereogenic center was inverted and the other stereoisomer ((R)-2i) was obtained. Both products were produced with high ee (>97%) as shown by chiral HPLC after desilylation. Therefore, this chemistry provides an economical protocol to produce optically pure compounds containing the dihydrobenzofuran structural unit (Fig. 4a).

Applications of the oxidative coupling reaction protocol. a Path 1. Synthesis of (R)-1i: 10, (S)-11, PPh3, Et3N, DIAD, THF, N2, 25 °C, 16 h, 85% isolated yield; LiOH·H2O, THF/H2O, 80 °C, 12 h, 93% isolated yield. i) CDC conditions: Pd(OAc)2, 1,4-BQ, Ag2CO3, Acridine, KH2PO4, NaOAc, tAmylOH, air, 140 °C, 24 h; MeI, K2CO3, DMF, 50 °C, 12 h. 60% isolated yield over two steps, 97% ee. Path 2. Synthesis of (S)-1i: Benzoic Acid, (S)-11, PPh3, Et3N, DIAD, THF, N2, 25 °C, 12 h, 90% isolated yield; NaOH, MeOH, reflux, 12 h, afford (R)-11, 95% isolated yield; 10, (R)-11, PPh3, Et3N, DIAD, THF, N2, 25 °C, 16 h, 85% isolated yield; LiOH·H2O, THF/H2O, 80 °C, 12 h, 95% isolated yield. i) CDC conditions: Pd(OAc)2, 1,4-BQ, Ag2CO3, Acridine, KH2PO4, NaOAc, tAmylOH, air, 140 °C, 24 h; MeI, K2CO3, DMF, 50 °C, 12 h. 62% isolated yield over two steps, 98% ee. b ii) 10, 12, PPh3, Et3N, DIAD, THF, N2, 25 °C, 16 h, 60% isolated yield; LiOH·H2O, THF/H2O, 80 °C, 12 h, 73% isolated yield. iii) CDC conditions: Pd(OAc)2, 1,4-BQ, Ag2CO3, Acridine, KH2PO4, NaOAc, tAmylOH, air, 140 °C, 24 h; 4-Nitrobenzyl bromide, K2CO3, DMF, 50 °C, 12 h. 44% NMR yield over two steps. c iv) 10, 14, PPh3, DIAD, THF, 25 °C, N2, 16 h, 74% isolated yield; TBAF, THF, rt, 80% isolated yield; 15, PPh3, DIAD, THF, 25 °C, N2, 16 h, 70% isolated yield; LiOH·H2O, THF/H2O, 80 °C, 12 h, 86% isolated yield. v) CDC conditions: Pd(OAc)2, 1,4-BQ, Ag2CO3, Acridine, KH2PO4, NaOAc, tAmylOH, air, 140 °C, 24 h. c. MeI, K2CO3, DMF, 50 °C, 12 h. 52% NMR yield over two steps

As alcohols are widely present in natural products, through the simple etheration/oxidative coupling, a wide range of functionalized compounds can be built up with high potential for drug discovery. With this in mind, we conducted the etheration of sterol 12 and the requisite phenol 10 to produce the ether. Oxidative coupling and esterification produced product 13 in 44% NMR yield. By combining three components, 10, 14, and estrone 15, compound 16 was constructed in three simple steps (Fig. 4b). This method efficiently builds up the complexity from natural and existing molecules for material chemistry and druggable scaffolds.

In summary, a new strategy was developed to carry out the intramolecular oxidative coupling between phenyl- and “inert” aliphatic carbon–hydrogen bonds with a broad functional group compatibility. The weakly coordinated carboxylate was found to be an effective directing group, and the proper ligand was essential for the success of this cross-coupling protocol yielding dihydrobenzofuran products from easily synthesized phenyl alkyl ethers. The carboxylic acid group can be transformed into a wide range of diverse functionalities, thus expanding the range of application of this method. Starting from the same commercially available chiral alcohols and readily synthesized phenols, both stereoisomers of corresponding dihydrobenzofurans were produced, thereby providing an economic route to make valuable complex molecules. With the developed strategy, the oxidative coupling between different carbon–hydrogen bonds shall have a great future to construct different carbon–carbon bonds in organic synthesis.

Methods

General procedure for oxidative coupling

To a 20 mL oven-dried glass tube, 1 (0.3 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), 1,4-BQ (20 mol%), Ag2CO3 (2.0 equiv), Acridine (20 mol%), KH2PO4 (1.0 equiv), NaOAc (1.5 equiv), and tAmylOH (2.0 mL) were added. The tube was sealed and the reaction mixture was stirred at 140 °C for 24 h under an air atmosphere. The mixture was cooled to rt. After removal of the solvent, MeI (5.0 equiv), K2CO3 (2.0 equiv), and DMF (3.0 mL) were added into the Schlenk tube. The mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 12 h. Then the suspension was filtered through a celite pad and washed with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL). The solvent was then removed in vacuo, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (PE/EtOAc = 100:1 to PE/EtOAc = 30:1) to afford the desired product 2.

For more specific procedures of the reaction treatment and compounds’ characterization method information, please refer to the Supplementary Methods. For NMR spectra of the compounds in this article, see Supplementary Figures 1–64.

Data availability

Accession codes: The X-ray crystallographic structures for 2ma reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1489220. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Bergman, R. G. Organometallic chemistry: C–H activation. Nature 446, 391–393 (2007).

Rousseaux, S. et al. Intramolecular palladium-catalyzed alkane C−H arylation from aryl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10706–10716 (2010).

Godula, K. & Sames, D. C-H bond functionalization in complex organic synthesis. Science 312, 67–72 (2006).

Daugulis, O., Do, H.-Q. & Shabashov, D. Palladium- and copper-catalyzed arylation of carbon-hydrogen bonds. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1074–1086 (2009).

Kuhl, N., Hopkinson, M. N., Delord, J. W. & Glorius, F. Beyond directing groups: transition-metal-catalyzed C-H activation of simple arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 10236–10254 (2012).

Girard, S. A., Knauber, T. & Li, C.-J. The cross-dehydrogenative coupling of C(sp3)-H bonds: a versatile strategy for C-C bond formations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 74–100 (2014).

Fier, P. S. & Hartwig, J. F. Selective C-H fluorination of pyridines and diazines inspired by a classic amination reaction. Science 342, 956–960 (2013).

Neufeldt, S. R. & Sandford, M. S. Controlling site selectivity in palladium-catalyzed C-H bond functionalization. Acc.Chem. Res. 45, 936–946 (2012).

Li, Y.-Z., Li, B.-J., Lu, X.-Y., Lin, S. & Shi, Z.-J. Cross dehydrogenative arylation (CDA) of a benzylic C-H bond with arenes by iron catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3817–3820 (2009).

Mo, F.-Y. & Dong, G.-B. C-H bond activation. Regioselective ketone α-alkylation with simple olefins via dual activation. Science 345, 68–72 (2014).

Stuart, D. R. & Fagnou, K. The catalytic cross-coupling of unactivated arenes. Science 316, 1172–1175 (2007).

Kita, Y. et al. Metal-free oxidative cross-coupling of unfunctionalized aromatic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1668–1669 (2009).

Wencel-Delord, J., Nimphius, C., Wang, H. & Glorius, F. Rhodium(III) and hexabromobenzene-a catalyst system for the cross-dehydrogenative coupling of simple arenes and heterocycles with arenes bearing directing groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 13001–13005 (2012).

Palucki, M., Wolfe, J. P. & Buchwald, S. L. Synthesis of oxygen heterocycles via a palladium-catalyzed C−O bond-forming reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 10333–10334 (1996).

Szlosek-Pinaud, M., Diaz, P., Martinez, J. & Lamaty, F. Efficient synthetic approach to heterocycles possessing 3,3-disubstituted-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran skeleton via diverse palladium-catalyzed tandem reactions. Tetrahedron 63, 3340 (2007).

Ren, H. & Knochel, P. Chemoselective benzylic C-H activations for the preparation of condensed N-heterocycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 3462–3465 (2006).

Aihara, Y., Tobisu, M., Fukumoto, Y. & Chatani, N. Ni (II)-catalyzed oxidative coupling between C (sp2)–H in benzamides and C (sp3)–H in toluene derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15509–15512 (2014).

Zhou, B. et al. Redox-neutral rhodium-catalyzed C-H functionalization of arylamine N-oxides with diazo compounds: Primary C(sp3)-H/C(sp2)-H activation and oxygen-atom transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 12121–12126 (2015).

Liegault, B. & Fagnou, K. Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular coupling of arenes and unactivated alkanes in air. Organometallics 27, 4841–4843 (2008).

Yang, W.-B. et al. Orchestrated triple C-H activation reactions using two directing groups: rapid assembly of complex pyrazoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2501–2504 (2015).

Zaitsev, V. G., Shabashov, D. & Daugulis, O. Highly regioselective arylation of sp3 CH bonds catalyzed by palladium acetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 13154–13155 (2005).

Chen, Z.-K. et al. Transition metal-catalyzed C–H bond functionalizations by the use of diverse directing groups. Org. Chem. Front 2, 1107–1295 (2015).

Lafrance, M., Gorelsky, S. I. & Fagnou, K. High-yielding palladium-catalyzed intramolecular alkane arylation: reaction development and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14570–14571 (2007).

Miura, M., Tsuda, T., Satoh, T., Pivsa-Art, S. & Nomura, M. Oxidative cross-coupling of N-(2’-phenylphenyl) benzene-sulfonamides or benzoic and naphthoic acids with alkenes using a palladium-copper catalyst system. J. Org. Chem. 63, 5211–5215 (1998).

Engle, K. M., Mei, T.-S., Wasa, M. & Yu, J.-Q. Weak coordination as a powerful means for developing broadly useful C–H functionalization reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 788–802 (2012).

Cheng, G.-L., Li, T.-J. & Yu, J.-Q. Practical Pd (II)-catalyzed C–H alkylation with epoxides: One-step syntheses of 3, 4-dihydroisocoumarins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137(1095), 0–10953 (2015).

Wang, D.-H., Engle, K. M., Shi, B.-F. & Yu, J.-Q. Ligand-enabled reactivity and selectivity in a synthetically versatile aryl C–H olefination. Science 327, 315–319 (2010).

Emmert, M. H., Gary, J. B., Janette, M., Villalobos, J. M. & Sanford, M. S. Platinum and palladium complexes containing cationic ligands as catalysts for arene H/D exchange and oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5884–5886 (2010).

Nakanishi, M., Katayev, D., Besnard, C. & Kündig, E. P. Fused indolines by palladium-catalyzed asymmetric C-C coupling involving an unactivated methylene group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7438–7441 (2011).

Ye, B.-H. & Cramer, N. Chiral cyclopentadienyl ligands as stereocontrolling element in asymmetric C–H functionalization. Science 338, 504–506 (2012).

Wu, X.-X., Fors, B. P. & Buchwald, S. L. A single phosphine ligand allows palladium-catalyzed intermolecular C-O bond formation with secondary and primary zlcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 9943–9947 (2011).

Lipshutz, B. H., Chung, D. W., Rich, B. & Corral, R. Simplification of the Mitsunobu reaction. Di-p-chlorobenzyl azodicarboxylate: a new azodicarboxylate. Org. Lett. 8, 5069–5072 (2006).

Sun, L.-Q. et al. N-{2-[2-(4-Phenylbutyl)benzofuran-4-yl]cyclopropylmethyl}acetamide: an orally bioavailable melatonin receptor agonist. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14, 5157–5160 (2004).

Huang, L.-B., Hackenberger, D. & Goosen, L. J. Decarboxylative cross-coupling of mesylates catalyzed by copper/palladium systems with customized imidazolyl phosphine ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1–6 (2015).

Walker, S. D., Barder, T. E., Martinelli, J. R. & Buchwald, S. L. A rationally designed universal catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 1871–1876 (2004).

Tichenor, M. S. et al. Asymmetric total synthesis of (+)-and ent-(-)-yatakemycin and duocarmycin SA: evaluation of yatakemycin key partial structures and its unnatural enantiomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 15683–15696 (2006).

Novak, P., Correa, A., Gallardo-Donaire, J. & Martin, R. Synergistic palladium- catalyzed C(sp3)-H activation/C(sp3)- O bond formation: a direct, step-economical route to benzolactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 12236–12239 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the “973” Project from the MOST of China (2013CB228102, 2015CB856600) and NSFC (Nos. 21332001, 21431008, 91645111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-J.S. conceived the concepts and ideas, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. J.-L.S., D.W., and X.-S.Z. contributed equally to this research. X.-S.Z. initiated the researches. J.-L.S. and D.W. conducted the experiments, collected the data, and prepared for the Supplementary Information. J.-L.S., D.W., X.-L.L., and Y.-Q.C. prepared the starting materials for experiments. Z.-J.S., and Y.-X.L. conducted the mechanistic researches.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, JL., Wang, D., Zhang, XS. et al. Oxidative coupling of sp 2 and sp 3 carbon–hydrogen bonds to construct dihydrobenzofurans. Nat Commun 8, 238 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00078-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00078-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.