Abstract

Background

Blood-stained tears can indicate occult malignancy of the lacrimal drainage apparatus. This study reviews data on patients presenting with blood in their tears and the underlying cause for this rare symptom.

Methods

Patients presenting with blood in their tears, identified over a 20-year period, were retrospectively collected from a single tertiary ophthalmic hospital’s database and analysed.

Results

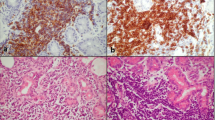

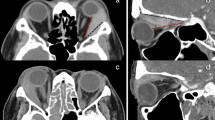

51 patients were identified, the majority female (58%) with a mean age of 55 years. Most cases were unilateral (96%) with blood originating from the nasolacrimal drainage system in 53%. The most common diagnosis for blood-stained tears was a lacrimal sac mucocele (n = 16) followed by a conjunctival vascular lesion (n = 4). Three patients had systemic haematological disorders. The rate of malignancy was 8% (n = 4), with 2 patients having lacrimal sac transitional cell carcinomas, one with a lacrimal sac plasmacytoma and the other with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and bilateral orbital infiltration (with bilateral bloody tears). One patient had a lacrimal sac inverted papilloma, a premalignant lesion. Four patients had benign papillomas (of the lacrimal sac, conjunctiva and caruncle).

Conclusion

Haemolacria was a red flag for malignancy in 8% of patients (and tumours in 18% of patients). A thorough clinical examination including lid eversion identified a conjunctival, caruncle, eyelid or canalicular cause in 27% of cases.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 18 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $14.39 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chon BH, Zhang R, Bardenstein DS, Coffey M, Collins AC. Bloody Epiphora (Hemolacria) years after repair of orbital floor fracture. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:e118–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000000839.

Murube J. Bloody tears: historical review and report of a new case. Ocul Surf. 2011;9:117–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1542-0124(11)70021-0.

Singh CN, Thakker M, Sires BS. Pyogenic granuloma associated with chronic Actinomyces canaliculitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:224–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.iop.0000214529.43021.f4.

Garcia GA, Bair H, Charlson ES, Egbert JE. Crying blood: association of valsalva and hemolacria. Orbit. 2021;40:266. https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2020.1768562.

Wiese MF. Bloody tears, and more! An unusual case of epistaxis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1051. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.87.8.1051.

Banta RG, Seltzer JL. Bloody tears from epistaxis through the nasolacrimal duct. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75:726–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(73)90829-5.

Wieser S. Bloody tears. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:286. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2011-200955.

Sen DK. Granuloma pyogenicum of the palpebral conjunctiva. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1982;19:112–4.

Vahdani K, Gupta T, Verity DH, Rose GE. Extension of masses involving the lacrimal sac to above the medial canthal tendon. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37:556–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001946.

Azari AA, Kanavi MR, Saipe N, Lee V, Lucarelli M, Potter HD, et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the lacrimal sac presenting with bloody tears. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:689–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2907.

Zhu LJ, Zhu Y, Hao SC, Huang P, Wang LL, Li XH, et al. Clinical experience on diagnosis and treatment for malignancy originating from the dacryocyst. Eye. 2018;32:1519–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-018-0132-1.

Li YJ, Zhu SJ, Yan H, Han J, Wang D, Xu S. Primary malignant melanoma of the lacrimal sac. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006349.

Wolf EJ, Wessel MM, Hirsch MD, Leib ML. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the nasolacrimal duct presenting as bloody epiphora. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23:242–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e31803ecf11.

Demir HD, Aydın E, Koseoğlu RD. A lacrimal sac mass with bloody discharge. Orbit. 2012;31:179–80. https://doi.org/10.3109/01676830.2011.648812.

Yazici B, Ayvaz AT, Aker S. Pyogenic granuloma of the lacrimal sac. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:57–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-007-9168-0.

Li E, Yoda RA, Keene CD, Moe KS, Chambers C, Zhang MM. Nasolacrimal lymphangioma presenting with hemolacria. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36:e118–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001622.

Lee H, Herreid PA, Sires BS. Bloody epiphora secondary to a lacrimal sac varix. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:e135–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e318281eca0.

Belliveau MJ, Strube YN, Dexter DF, Kratky V. Bloody tears from lacrimal sac rhinosporidiosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47:e23–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.03.019.

Eiferman RA. Bloody tears. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:524–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(82)90147-7.

Di Maria A, Famà F. Hemolacria—crying blood. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1766. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMicm1805241.

Maxted G. Pedunculated haemangeioma of conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. 1919;3:429–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.3.9.429.

Legrand J, Hervouet F, Loue J. Case of dacryohemorrhysis. Bull Soc Ophtalmol Fr. 1976;76:307–8.

Bakker A. A MYXO-HAEMANGIOMA SIMPLEX OF THE CONJUNCTIVA BULBI. Br J Ophthalmol. 1948;32:485–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.32.8.485.

Yazici B, Ucan G, Adim SB. Cavernous hemangioma of the conjunctiva: case report. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:e27–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181c4e3bf.

Krohel GB, Duke MA, Mehu M. Bloody tears associated with familial telangiectasis. Case Rep Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1489–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1987.01060110035020.

Soong HK, Pollock DA. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia diagnosed by the ophthalmologist. Cornea. 2000;19:849–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200011000-00017.

Rodriguez ME, Burris CK, Kauh CY, Potter HD. A conjunctival melanoma causing bloody tears. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33:e77. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000000765.

BELAU PG, RUCKER CW. Bloody tears: report of case. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1961;36:234–8.

Bonavolontà G, Sammartino A. Bloody tears from an orbital varix. Ophthalmologica. 1981;182:5–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000309082.

Mukkamala K, Gentile RC, Rao L, Sidoti PA. Recurrent hemolacria: a sign of scleral buckle infection. Retina. 2010;30:1250–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181d2f15e.

Kemp PS, Allen RC. Bloody tears and recurrent nasolacrimal duct obstruction due to a retained silicone stent. J AAPOS. 2014;18:285–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.12.011.

Sbrana MF, Borges RFR, Pinna FR, Neto DB, Voegels RL. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: rate of recurrence and malignant transformation in 44 operated patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;87:80–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2019.07.003.

Gião Antunes AS, Peixe B, Guerreiro H. Hematidrosis, hemolacria, and gastrointestinal bleeding. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2017;24:301–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000461591.

Siggers DC. Bloodstained tears. Br Med J. 1970;4:177. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5728.177-b.

Ho VH, Wilson MW, Linder JS, Fleming JC, Haik BG. Bloody tears of unknown cause: case series and review of the literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:442–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.iop.0000143713.01616.cf.

Silva GS, Nemoto P, Monzillo PH. Bloody tears, gardner-diamond syndrome, and trigemino-autonomic headache. Headache. 2014;54:153–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12226.

Fowler BT, Kosko MG, Pegram TA, Haik BG, Fleming JC, Oester AE. Haemolacria: a novel approach to lesion localization. Orbit. 2015;34:309–13. https://doi.org/10.3109/01676830.2015.1078371.

Beyazyıldız E, Özdamar Y, Beyazyıldız Ö, Yerli H. Idiopathic bilateral bloody tearing. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2015;2015:692382. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/692382.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and/or designed the work that led to the submission, acquired data, and/or played an important role in interpreting the results—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. Drafted or revised the paper—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. Approved the final version—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved—MK, VJ, DGE, DHV, JU, HT. As corresponding author, MK, confirms that she has had full access to the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaushik, M., Juniat, V., Ezra, D.G. et al. Blood-stained tears—a red flag for malignancy?. Eye 37, 1711–1716 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02224-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02224-x