Abstract

Background

Direct referrals from optometrists account for up to 10% eye casualty attendances. Despite this, there remains a paucity of literature on optometrist referrals to eye casualty. A better understanding of these referrals could be helpful in the development of shared care emergency pathways. Diagnostic agreement between optometrists and ophthalmologists for emergency referrals can be used to identify areas for development of shared care working strategies in emergency ophthalmology.

Methods

A retrospective evaluation of 1059 consecutive optometric emergency referrals to Moorfields Eye Hospital was conducted. Referrals were only included when a letter or documentation for the reason for referral was provided. Diagnostic information from the referring optometrist and casualty doctor was summarised for each patient by an investigator (VMT) and recorded on a single spreadsheet. These clinical summaries were compared by a second independent investigator (IJ) and marked as agreeing, disagreeing or uncertain. Each clinical summary was then mapped to a diagnostic category using key word searches which were manually re-checked against the original summaries. Information on the timing of the referral and the outcome at the emergency department visit was also collated. Inter-observer agreement for diagnostic categories was measured using kappa coefficients.

Results

Diagnostic agreement ranged between kappa 0.59 and 0.87. It was best for diagnoses within the red eye category (kappa 0.87). Compliance with College of Optometrists referral guidance ranged between 11 and 100%. More than half of referrals for elevated intra-ocular pressure were discharged at the eye casualty visit. Overall, 54% of patients were managed with advice alone, 39% required treatment following referral and 7% required onward referral from eye casualty.

Conclusion

The majority of patients referred by optometrists were managed with advice alone. A collaborative approach at the point referral could be helpful to improve referral efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is growing demand on emergency eye services in the UK [1,2,3]. While there is a clear need for specialised assessment and treatment, almost 80% of those attending eye casualty do not require urgent ophthalmic attention following triage [4] and up to 60% of patients are seen and discharged at their first visit [5]. It is possible that many of these attendances could be redirected. It is estimated that 40% of eye casualty referrals could be managed in primary care [4] or by other providers with appropriate training.

Traditionally, optometrists provide services including fitting contact lenses, testing of sight and the sale and supply of optical appliances. This is governed by the Opticians Act [6]. However, over recent years there has been an increase in ‘enhanced services’ whereby optometrists are taking on additional clinical roles traditionally performed by ophthalmologists. This is more common within the hospital eye sector [7]. A number of studies have shown good diagnostic concordance between optometrists and ophthalmologists [8,9,10,11] and a number of optometrist-based schemes in the emergency ophthalmology sector, including Minor Eye Conditions Services (MECS) [12] and Primary Eye Care Referral and Assessment Service (PEARS) [13], have been developed and trialled.

MECS and PEARS schemes are NHS-funded intermediate-tier services (ITS). Patients can reach ITS either by self-referral, by another community optometrist or general practitioners (GP).

MECS and PEARS services are designed to allow accredited optometrists to use their skills to triage, manage and prioritise patients presenting with minor eye conditions [14]. This is an attempt to avoid unnecessary referral and when referral is required this is done with the appropriate urgency and to the correct practitioner.

Where direct access to eye casualty is available, the majority of patients self-refer. Referrals from optometrists account for up to 10% of attendances [5] with a similar proportion attending via their GP [5, 15, 16]. Despite this, there remains a paucity of literature on emergency referrals from optometrists to eye casualty.

A better understanding of these referrals and areas of discordance could be used to identify uncertainty and facilitate the development of shared care working strategies.

The aim of this study was to analyse current referral practice from optometrists to a busy city emergency ophthalmology centre and to determine the diagnostic agreement between optometrists and ophthalmologists for ocular pathology. Diagnostic discordance was defined as:

-

1.

Where the referring optometrist’s diagnosis was unrelated to the diagnosis made in eye casualty and not reliant on equipment available to them and/or;

-

2.

Where the referring optometrist identified pathology which was not apparent when they were reviewed by the eye casualty doctor.

Methods

All optometric referrals to Moorfields Eye Hospital eye casualty service over a 6-month period from April 2016 to September 2016 were retrospectively reviewed and diagnostic agreement assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Referrals included were all those where an optometrist had provided the patient with a letter explaining the reason for referral. Any referrals made where no letter had been provided or no documented reason for referral was found were excluded from our study.

Information from the original optometrist referral including the reason for attending, duration of symptoms, clinical findings and diagnosis were summarised and transcribed onto an excel spreadsheet in a standard format by a single fellowship trained ophthalmologist (VMT). Patients were seen in eye casualty by an ophthalmologist and clinical information from the hospital visit, timing and outcome were recorded in a similar manner to that collected from the referral.

The summaries of diagnostic information for each patient from the optometrist and hospital were compared by a second investigator (IJ) who categorised them as agreeing, disagreeing or uncertain. Where the diagnosis was not identical but broadly similar (e.g., blepharitis and dry eye) or otherwise appropriate (e.g., flashes and floaters referred to rule out retinal tear) it was classified as agreeing.

The diagnostic summaries were also automatically mapped to 58 diagnoses grouped under 7 ophthalmic sub-specialty headings (Table 1). These diagnoses were based on common terms found in the original data and the presence or absence of each diagnosis was treated as binary categorical variables (i.e., yes/no). Agreement was measured separately for each diagnosis and also for each sub-specialty heading. Inter-observer agreement was assessed using kappa coefficients. We used the cut-offs proposed by Landis and Koch [17] to classify the level of agreement. Fleiss’ kappa ranges from −1 to +1, with negative values suggesting agreement less than that which would have occurred by chance. Values of 0–0.2 suggest poor agreement, 0.2–0.4 fair agreement. Values of 0.6–0.8 suggest good agreement and 0.8–1 suggest very good agreement. Data management and analysis were performed using Stata v14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

For conditions where referral practices have established standards for timing of referral we determined compliance with College of Optometrists guidance for the maximum interval within which the patient should be seen.

Results

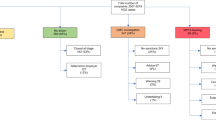

There were 1059 consecutive cases recorded over the study period. The mean age was 46 (SD 16.8, range 16–99) and 60% were female. Diagnoses were mapped to 25 anterior segment, 25 posterior segment and 8 symptoms/sign-based categories. These were grouped under seven sub-specialty headings. The original reason for visiting the referring optometrist is shown in Table 2. Overall diagnostic agreement by sub-specialty along with hospital outcome is shown in Table 1. Agreement for common diagnoses grouped under ‘anterior segment/red eye’ is shown in Table 3.

The most common reason for referral was anterior segment disease/red eye accounting for 427 (40%) patients. This was followed by vitreo-retinal disease, with 208 (20%) patients having flashes, floaters and related symptoms or clinical findings detected incidentally after asymptomatic presentation. The referring optometrist performed a dilated examination in 61% of these, while 29% were referred without prior dilation. Dilation status was unclear in the remaining 10%. No patients required laser or intervention. Nine patients were diagnosed with retinal tears. The agreement for detecting retinal breaks was Kappa 0.35. There were six referrals that mentioned tobacco dust as being present or possibly present from their referring optometrist. Of these six patients, one patient was found to have asteroid hyalosis. The remaining were not found to have tobacco dust and no retinal detachment/break was identified. All other referrals did not show tobacco dust as being present. Patients referred with retinal breaks had operculated holes or asymptomatic atrophic holes associated with retinal degeneration. As such, none of these patients required any intervention [18] and were discharged with advice alone. A further two patients were diagnosed with vitreous haemorrhage secondary to posterior vitreous detachment and referred onwards to the vireo-retinal clinic as they are likely to have a retinal break or detachment [19]. Seven patients were referred in with a possible retinal detachment. Of these seven patients none were found to have a retinal detachment. One patient was referred in as macula-off retinal detachment and was diagnosed with Wet Active AMD.

There were 19 (2%) cases referred with unexplained reduced acuity, none had urgent pathology. Just over half (53%) were discharged with advice only. Ninety-six (9%) patients were referred with neurological signs and symptoms, including 76 (79%) with possible disc pathology. The casualty doctors agreed that the optic disc was suspicious in 36% of cases.

Most patients attended their optometrist following the development of symptoms but 209 (20%) were referred following a routine sight test during which they were found to have incidental symptoms or signs. Of these 209 patients there were 49 (5%) with red eye, 44 (4%) with PVD, 63 (6%) with retinal pathology, 29 (3%) with abnormal neurology, 18 (2%) with raised intra-ocular pressure (IOP) and 6 (0.6%) with reduced acuity. No diagnosis was offered by the optometrist in 59 (6%) cases. Among patients with incidental findings, agreement between eye casualty doctors and the referring optometrist was 53%.

Thirty-two per cent (49/155) of patients in the medical retina category were referred with suspected AMD. The next most frequent diagnoses were retinal vein occlusion (12), diabetic retinopathy (8), retinal scar (7). The remainder had a wide range of diagnoses including epiretinal membrane, macular oedema and suspected retinal degenerations.

The College of Optometrists has produced guidance for optometrists regarding emergency referrals (Appendix) [20] as well as for posterior vitreous detachment [21]. Compliance of the referrals from our sample with the College of Optometrist Referral Criteria is shown in Table 4.

Discussion

The majority of optometrist referrals were not ophthalmic emergencies. Only 39% of patients required treatment following referral and 54% were managed with advice alone. The remaining 7% were referred onwards. This is in keeping with previous research which has shown up to 56% of referrals are discharged at their first casualty visit [5, 15, 16]. Thus, the majority of patients referred by optometrists were managed with advice alone. These patients did not require treatment within a tertiary centre but still needed expertise beyond that available with their own optometrist. A collaborative approach at the point referral may be helpful to improve referral efficiency.

A more collaborative approach for referral guideline development would also be helpful. These findings may explain why there are many local eye casualty referral policies which supersede the current referral guidelines.

Attempts to improve efficiency by filtering referrals have had limited success with studies on cost effectiveness of MECS and PEARS schemes showing equivocal results [13, 22, 23]. Providing access to advice at the point of referral may be more helpful.

While generally good, diagnostic agreement varied substantially according to sub-specialty and diagnosis. It was best for anterior segment disease, within which it was highest for CLAK. Agreement was lower for episcleritis/scleritis, conjunctivitis and uveitis. The majority (80%) of patients with anterior segment disease required treatment, posing a further challenge for shared care schemes. Even when a diagnosis can be confidently made, prompt and appropriate treatment is critical to success.

PVD and related symptoms were common. None of the patients in this sample were found to have a retinal detachment but this was suggested by the referring optometrist in seven instances. Referral in the absence of definitive findings is reasonable in these circumstances but a high proportion was sent without having undergone a dilated examination. This may be because the current general ophthalmic service (GOS) fee structure does not provide reimbursement for all ancillary tests or symptomatic patients; or because there was a high index of suspicion which rendered primary assessment redundant. Our study may also have missed those patients referred directly to the vitreo-retinal team from their optometrist or enhanced community services.

Similarly, suspected optic disc swelling was the cause for referral in 76 patients but only 36% were thought to be suspicious at the subsequent eye casualty examination. This likely represents ‘safe practice’. As with PVD, the consequences of a missed diagnosis can be catastrophic and having a low threshold for referral is not unreasonable; but may lead to morbidity from over-investigation and over-treatment. There has been a marked increase in neuro-imaging [24] following the prosecution of an optometrist after a case of missed papilloedema.

Just over half of referrals for raised IOP were discharged with advice. The updated NICE guidance has increased the threshold for referral to IOP ≥ 24 mmHg [25] but this can still lead to over referral especially where non-contact tonometers are used. Repeated testing with Goldmann tonometry [26, 27] has been successfully used to reduce false-positive referrals and also within the Scottish GOS contract through the use of supplementary glaucoma payments [28, 29].

Thirty-two per cent (49/155) of patients in the medical retina category were referred with suspected AMD. These would have been better referred to a macula service, in accordance with NICE guidance [30]. Furthermore, only 19% of patients required onward referral to a specialist medical retina clinic. This suggests that a significant number (80%) of the patients seen in our sample could have been managed in primary care.

We found variable compliance with college standards for triage and timings of referral. This may be due to variations in experience and individual risk perception by the referring practitioner or the patients’ perception of urgency. A patient may have been referred urgently but chose to attend at a more convenient time. The converse may also be true, and patients have presented to eye casualty despite having been referred via an alternative route. In areas where local referral criteria exist, these may supersede the College of Optometrists recommendations limiting the applicability of this standard.

Limitations

The size of our sample and independent assessment of optometrist and hospital outcomes are strengths of this work, along with the combined approach to measures of agreement. An important confounder is the fact that MEH is a ‘walk-in’ department with 24 hour 7 day open-access. There is, therefore, no need for optometrists to discuss referrals with the ophthalmologists as the patient will always be seen. As a result, onward referral could be viewed as ‘safe practice’, which may also be reflective of the wait to see an ophthalmologist for non-urgent referrals. In addition, these results are for a single centre and our findings may not necessarily be generalisable to other units. Results would still be expected to be representative of the main types of pathology encountered. Given that not all patients seen by optometrists were referred, it is not possible to determine true/false negative rates from this type of study. The concurrent running of established MECS pathways across London may have impacted upon the referrals and as such findings may not necessarily be generalisable. Furthermore, the experience and additional qualifications of those referring and those assessing patients in eye casualty were not determined and this may influence the overall results of our study if this was not reflective of normal workforce patterns. Finally, it is possible that not all pathology was detected at the eye casualty visit.

Conclusions

These results highlight some of the areas where collaboration between primary and secondary care could be improved. However, implemented change is, to some extent, limited by the current structure of services within which optometrists operate. Criticism that optometrists generate high false positives and are incentivised to do so [31] is countered by the fact that optometrists are ‘…not funded to accept risk or co-operate with the NHS failing to meet escalating demands’. Furthermore, maintaining financial viability in socio-economically deprived communities requires income from services beyond sight-testing, such as community services [32]. Risk management behaviour was noticeable in referral patterns for PVD and suspected disc swelling and may have had a confounding effect for agreement on other diagnoses beyond this. Management of clinical risk will be a key determinant of how far shared care working can progress and mitigating this limitation will require reform of traditional modes of working to include a more blended approach between primary and secondary care. The ‘Education Strategic Review’ led by the General Optical Council [33] recognises the need to reform optometric undergraduate education and continuing education to reflect these increasing demands, whilst maintaining patient safety.

The face of emergency ophthalmology is rapidly changing. Optometrists can provide a pivotal role in helping to alleviate the pressures of increasing demand on secondary care services and many are already taking part in enhanced emergency service schemes, at all levels of care. The training structures for these schemes may lack the necessary clinical exposure and decision-making skills to allow optometrists to optimise the refined patient pathway. Most medical education is now delivered in line with Bruner’s spiral curriculum [34] and it may be that optometry teaching would benefit from a similar shift along with the development of governance frameworks that recognise these new multi-disciplinary patterns of working. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists is leading a collaborative project [35], looking to develop allied health emergency practitioners in secondary care. Our paper highlights some of the needs that should be addressed when considering successful design and implementation of such schemes.

Summary

What was known before

-

There is growing demand on emergency eye care services.

-

Intermediate-tier services (ITS) have been utilised to attempt to meet these demands.

-

The clinical skills needed to deliver these services and the training needs of optometrists have not been clearly defined.

What this study adds

-

We found over half of referrals were managed with advice alone.

-

Risk management referral behaviour was notable for PVD and disc swelling referrals.

-

Differential diagnosis of red eye, raised intra-ocular pressure and neuro-ophthalmic presentations should be of importance when considering training provision for ITS.

References

Smith HB, Daniel CS, Verma S. Eye casualty services in London. Eye. 2013;27:320–8.

Siempis T. Urgent eye care in the UK increased demand and challenges for the future. Med Hypothesis Disco Innov Ophthalmol. 2014;3:103–10.

Kadyan A, Sandramouli S, Caruana P. Utilization of an ophthalmic casualty-a critical review. Eye Lond Engl. 2007;21:441–2.

Kadyan A, Sandramouli S, Caruana. P. [Internet]. 2017. http://www.escrs.org/esont/publications/journal/2007/1/reorgophthalmic200807abs.pdf.

Hau S, Ioannidis A, Masaoutis P, Verma S. Patterns of ophthalmological complaints presenting to a dedicated ophthalmic accident & emergency department: inappropriate use and patients’ perspective. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:740–4.

Opticians Act 1989 [Internet]. 2019. https://www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/opticians_act.cfm.

Harper R, Creer R, Jackson J, Ehrlich D, Tompkin A, Bowen M, et al. Scope of practice of optometrists working in the UK Hospital Eye Service: a national survey. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36:197–206.

Vernon SA. Analysis of all new cases seen in a busy regional centre ophthalmic casualty department during 24-week period. J R Soc Med. 1983;76:279–82.

Banes MJ, Culham LE, Bunce C, Xing W, Viswanathan A, Garway‐Heath D. Agreement between optometrists and ophthalmologists on clinical management decisions for patients with glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:579–85.

Fung M, Myers P, Wasala P, Hirji N. A review of 1000 referrals to Walsall’s hospital eye service. J Public Health. 2016;38:599–606.

Marks JR, Harding AK, Harper RA, Williams E, Haque S, Spencer AF, et al. Agreement between specially trained and accredited optometrists and glaucoma specialist consultant ophthalmologists in their management of glaucoma patients. Eye. 2012;26:853–61.

Konstantakopoulou E, Edgar DF, Harper RA, Baker H, Sutton M, Janikoun S, et al. Evaluation of a minor eye conditions scheme delivered by community optometrists. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011832.

Sheen NJL, Fone D, Phillips CJ, Sparrow JM, Pointer JS, Wild JM. Novel optometrist-led all Wales primary eye-care services: evaluation of a prospective case series. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:435–8.

MECS [Internet]. LOCSU. 2019. https://www.locsu.co.uk/commissioning/pathways/minor-eye-conditions-service/.

Fenton S, Jackson E, Fenton M. An audit of the ophthalmic division of the accident and emergency department of the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital, Dublin. Ir Med J. 2001;94:265–6.

Wasfi EI, Sharma R, Powditch E, Abd-Elsayed AA. Pattern of eye casualty clinic cases. Int Arch Med. 2008;1:13.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Byer NE. What happens to untreated asymptomatic retinal breaks, and are they affected by posterior vitreous detachment? Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1045–50.

Hollands H, Johnson D, Brox AC, Almeida D, Simel DL, Sharma S. Acute-onset floaters and flashes: is this patient at risk for retinal detachment? JAMA. 2009;302:2243–9.

The College of Optometrists [Internet]. Urgency of referrals. 2020. http://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/communication-partnership-and-teamwork-domain/working-with-colleagues/urgency-of-referrals/.

The College of Optometrists [Internet]. Examining patients who present with flashes and floaters. 2017. http://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/knowledge-skills-and-performance-domain/examining-patients-who-present-with-flashes-and-floaters/?searchtoken=posterior+vitreous+detachment.

Mason T, Jones C, Sutton M, Konstantakopoulou E, Edgar DF, Harper RA, et al. Retrospective economic analysis of the transfer of services from hospitals to the community: an application to an enhanced eye care service. BMJ Open. 2017;10:e014089. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014089.

Baker H, Ratnarajan G, Harper RA, Edgar DF, Lawrenson JG. Effectiveness of UK optometric enhanced eye care services: a realist review of the literature. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36:545–57.

Poostchi A, Awad M, Wilde C, Dineen RA, Gruener AM. Spike in neuroimaging requests following the conviction of the optometrist Honey Rose. Eye. 2017;32:489.

Glaucoma: diagnosis and management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE [Internet]. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng81/chapter/Recommendations.

Parkins DJ, Edgar DF. Comparison of the effectiveness of two enhanced glaucoma referral schemes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011;31:343–52.

Vernon SA, Hillman JG, MacNab HK, Bacon P, Hoek J, van der, Vernon OK, et al. Community optometrist referral of those aged 65 and over for raised IOP post-NICE: AOP guidance versus joint college guidance—an epidemiological model using BEAP. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1534–6.

El-Assal K, Foulds J, Dobson S, Sanders R. A comparative study of glaucoma referrals in Southeast Scotland: effect of the new general ophthalmic service contract, Eyecare integration pilot programme and NICE guidelines. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:172.

Ang GS, Ng WS, Azuara-Blanco A. The influence of the new general ophthalmic services (GOS) contract in optometrist referrals for glaucoma in Scotland. Eye. 2009;23:351–5.

Recommendations | Age-related macular degeneration | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng82/chapter/Recommendations#diagnosis-and-referral.

Clarke M. NHS sight tests include unevaluated screening examinations that lead to waste. BMJ. 2014;348:g2084.

Addressing inequalities in eye health with subsidies and increased fees for General Ophthalmic Services in socio-economically deprived communities: a sensitivity analysis—ScienceDirect [Internet]. 2019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033350614001917?via%3Dihub.

Education Strategic Review [Internet]. 2018. https://www.optical.org/en/Education/education-strategic-review/index.cfm.

Harden RM. What is a spiral curriculum? Med Teach. 1999;21:141–3.

Opthalmologists TRC of. Ophthalmology Common Clinical Competency Framework [Internet]. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. 2018. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/professional-resources/new-common-clinical-competency-framework-to-standardise-competences-for-ophthalmic-non-medical-healthcare-professionals/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. College of Optometrists guidance for optometrists regarding emergency and urgent referral

Appendix. College of Optometrists guidance for optometrists regarding emergency and urgent referral

Emergency referral (within 24 h), symptoms or signs suggesting:

Acute glaucoma

acute dacryocystitis in children, or in adults if severe cellulitis (preseptal or orbital)

corneal foreign body penetrated into stroma, or with presence of a rust ring (unless optometrist is specifically trained in rust ring removal)

CRAO

Endophthalmitis

facial palsy, if new or with loss of corneal sensation

herpes zoster ophthalmicus with acute skin lesions (emergency referral to GP for systemic anti-viral treatment with urgent referral to ophthalmology if deeper cornea involved)

hyphaema

hypopyon

IOP ≥ 40 mmHg (independent of cause)

microbial keratitis

orbital cellulitis

papilloedema

penetrating injuries

pre-retinal haemorrhage, although a pre-retinal haemorrhage in a diabetic patient with known proliferative retinopathy who is already being actively treated in the HES would not need an emergency referral

retinal detachment unless this is long-standing and asymptomatic

scleritis

sudden severe ocular pain

suspected temporal arteritis

symptomatic retinal breaks and tears

third nerve palsy with pain

trauma (blunt or chemical), if severe

unexplained sudden loss of vision

uveitis

vitreous detachment symptoms with pigment in the vitreous, or

viral conjunctivitis if severe (e.g., presence of pseudomembrane)

Urgent referral (within 1 week), symptoms or signs suggesting:

acute dacryoadenitis

acute dacryocystitis if mild

atopic keratoconjunctivitis with corneal epithelial macro-erosion or plaque

unilateral blepharitis if carcinoma suspected

chlamydial conjunctivitis (refer to GP)

CMV and candida retinitis

commotio retinae

corneal hydrops if vascularisation present

CRVO with elevated IOP (40 mmHg refer as emergency)

herpes zoster ophthalmicus with deeper corneal involvement—urgent referral to ophthalmology, but refer to GP as an emergency for systemic anti-viral treatment

IOP > 35 mmHg (and <40 mmHg) with visual field loss

keratoconjunctivitis sicca if Stevens–Johnson syndrome or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid are suspected

retinal detachment if not an emergency, see above

retrobulbar/optic neuritis

ocular rosacea with severe keratitis

rubeosis

squamous cell carcinoma

steroid induced glaucoma

sudden onset diplopia

vernal keratoconjunctivitis with active limbal or corneal involvement, or

‘wet’ macular degeneration/choroidal neovascular membrane, according to local fast-track protocol.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mas-Tur, V., Jawaid, I., Poostchi, A. et al. Optometrist referrals to an emergency ophthalmology department: a retrospective review to identify current practise and development of shared care working strategies, in England. Eye 35, 1340–1346 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-1049-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-1049-z

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing Ophthalmic Triage: identification of new clinical features to support healthcare professionals in triage

Eye (2024)

-

Usability of an artificially intelligence-powered triage platform for adult ophthalmic emergencies: a mixed methods study

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Evaluation of the Manchester COVID-19 Urgent Eyecare Service (CUES)

Eye (2022)