Abstract

Purpose

To report the clinical and histopathologic features of two cases of eyelids metastases from uveal melanoma diagnosed in a metachronous and synchronous fashion.

Methods

Monocentric retrospective case series of histopathologically proven eyelids metastases from uveal melanoma at our institution.

Results

Two patients were presented to our hospital for upper eyelids pigmented and firm lesions. Patient 1 had an history of left uveal melanoma treated conservatively with proton beam therapy 5 years earlier. Examination revealed bilateral upper eyelids lesions. Patient 2 had no malignancy history but was incidentally diagnosed with a cerebral nodule few months earlier. Examination revealed a right upper eyelid nodule and a previously unknown right uveal melanoma. Excisional biopsy was performed for both patients. Pathological assessment allowed the presence of melanoma cells. The lack of BAP1 nuclear expression on immunohistochemistry as well as the absence of cutaneous or mucosal melanoma were consistent with an uveal origin. Diffuse metastatic spread was noted for both patients. Systemic therapies were prescribed. Patient 1 died from metastatic spread (62 months and 4 months after uveal melanoma diagnosis and eyelids metastases removal, respectively) whereas patient 2 was still alive (14 months follow up).

Conclusions

Eyelids metastases from uveal melanoma is an exceptional finding. Excisional biopsy and pathological assessment are of main importance to confirm the diagnosis and to identify genetic mutations for further targeted therapies. Currently, prognosis remains poor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Melanoma located to the eyelids is usually the result of local spread of conjunctival melanoma or primary skin melanoma. Eyelid metastasis of melanoma is a very uncommon condition mostly related to metastatic skin melanoma [1].

Although uveal melanoma is a rare tumor, it represents the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults. Despite the efficiency of local treatments on primary uveal melanoma, about 15 and 25% of patients will develop further metastases at 5 and 10 years, respectively [2]. Liver is the most common metastatic site followed by lungs and bones [3]. Uveal melanoma eyelid metastasis is an exceptional finding and less than 12 cases have been previously reported.

We herein report clinical and histopathologic features of two cases of eyelids metastases from uveal melanoma diagnosed in a metachronous and synchronous fashion.

Case reports

Patient N°1

A 67-year-old man was diagnosed with choroidal melanoma of the left eye in 2011 (Fig. 1a). The patient underwent conservative treatment with proton beam therapy (60 Gy) with favorable outcome. Clinical, biological, and radiological follow-ups were unremarkable during 2 years. In 2013, liver metastases were diagnosed and histologically confirmed. Systemic work-up did not reveal other metastases. Neither skin nor mucosal melanoma was found. Interferon immunotherapy was prescribed. In 2015, a left intra-choroidal metastasis was found on fundus examination (Fig. 1b) treated by laser photocoagulation. In 2016, the patient developed multiple painless subcutaneous pigmented nodules on his face (Fig. 1c). Two of them involved his upper eyelids (Fig. 1d) and were responsible of a mechanical ptosis especially on the right side. Palpation revealed firm and mobile lesions. Eversion of the right upper eyelid showed a full thickness pigmented eyelid mass. No bulbar conjunctival or scleral invasion was noted bilaterally. Complete ophthalmological examination of the right eye was unremarkable, whereas left fundus showed two chorioretinal atrophic areas in the previously treated choroidal melanoma. Orbital examination did not find any mass, limitation of oculomotor muscles, or proptosis. No regional lymph nodes were noted. Systemic work-up revealed liver, cerebral. and multiple subcutaneous metastases.

a Left fundus photography demonstrating a large pigmented choroidal mass of the posterior pole with orange pigment over its surface and serous retinal detachment located between the optic nerve and macula. b High field retinophotography demonstrating an intra-choroidal metastasis inferonasal to the previously treated choroidal melanoma. c More than ten black subcutaneous metastases are noted on the patient’s face. d Eyes closed. Note the bilateral subcutaneous upper eyelids metastases. e The eyelid and the tarsal plate were infiltrated by a mixed population of spindle and small epithelioid cells with moderate nuclear pleomorphism. Magnification 126 × ; stain: hematoxylin-eosin. f By immunohistochemistry, there was a loss of nuclear expression of BAP1 (red arrows)Magnification: 126 ×

Palliative eyelid surgery was performed with excision of the two nodules under local anesthesia.

Pathological analysis revealed a proliferation of spindle and epithelioid cells were organized in sheets without back to back loops. There was a moderate nuclear pleomorphism. There was one mitose /10 HPF (1.8 mm2) and no necrosis was noted. The tumor cells were also infiltrating the conjunctival epithelium (Fig. 1e). The tumor cells were expressing Melan A and there was loss of BAP 1 nuclear expression (Fig. 1f).

The patient died from his metastatic spread 62 and 4 months after the diagnosis of uveal melanoma and eyelids metastases removal, respectively.

Patient N°2

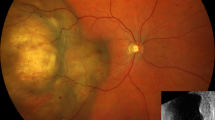

A 57-year-old male complained of painless right visual impairment. Right visual acuity was reduced to 20/200. Anterior slit lamp examination was unremarkable excepting a right external upper eyelid nodule located in the tarsus consistent with a tumor of unknown origin. Right fundus revealed a posterior pole uveal melanoma (Fig. 2a). Patient’s history indicated that a cerebral nodule was incidentally diagnosed 3 months earlier in the course of a following a minor head injury. Systemic work-up demonstrated additional liver and lung lesions without skin and mucosal melanomas. One month after, the patient presented with a right, firm, 7 × 7 mm, pigmented upper eyelid nodule without conjunctival involvement and madarosis (Fig. 2b). No ptosis, proptosis or extraocular movement restriction was noted. Fellow eye examination was unremarkable.

a Fundus photography demonstrating a right melanoma of the posterior pole. b Pigmented external upper eyelid nodule measuring 7 × 7 mm without ptosis or madarosis. c Pathological findings: the dermis is filled with sheets of large and atypical epithelioid cells. Scattered pigmented melanophages can also be observed. Magnification 126 × ; stain: hematoxylin-eosin. d There was a loss of BAP1 nuclear expression by immunohistochemistry (white arrows). Positive nuclear expression can be observed in the overlaying epidermis (black arrows) Magnification: 126 ×

Excisional biopsy was performed under local anesthesia. Pathological examination identified a proliferation of epithelioid cells (Fig. 2c) without back to back loops. Nuclear pleomorphism was moderate. There was one mitose /10 HPF (1.8 mm2) and no necrosis was noted. The tumor cells were expressing Melan A and there was loss of BAP1 nuclear expression (Fig. 2d).

The patient underwent proton beam therapy. An anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was prescribed. Follow up at one year revealed no eyelid recurrence, satisfactory regression of the uveal melanoma without toxic syndrome, and systemic neoplastic spread control. While writing this article, the patient is still alive with 14 months of follow up.

Discussion

Uveal melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adulthood [4]. Although conservative treatments (proton beam therapy and brachytherapy) or non-conservative treatments (enucleation) are very efficient therapies for the local control of uveal melanoma, it is estimated that 15–25% of patients will develop metastases after 5 and 10 years follow up, respectively, [2] regardless successful treatment of the primary tumor. Liver is the most common metastatic site (95%) followed by lungs (24%), bones (16%), and skin (11%) [3]. Other metastatic locations have been described: eyelids [5], spine [6], breast [7], and ovarian [8]. Hematogenous spread is thought to be the underlying mechanism. Intra-choroidal metastases, as described in our first case, has been previously published [9].

Metastatic risk factors have been identified, such as greater tumor size, extra scleral invasion, epithelioid histology, and greater mitotic number. New genetic prognostic factors, such as monosomy 3, 8q gain, and loss of BAP1 nuclear expression have also been identified and seem to be the strongest indicators of the metastatic spread risk [10,11,12]. Recently, Shields et al. [13] demonstrated a relationship between uveal melanoma thickness and cytogenetic alterations.

In our context, the presence of intraocular pigmented mass, the absence of other cutaneous or mucosal melanoma, as well as the the loss of BAP1 nuclear expression were consistent with eyelid metastatic extension of uveal melanoma. BAP1 mutations were identified in 84% of metastatic uveal melanoma [14], and this event is thought to occur later in tumor development.

Prognosis of metastatic uveal melanoma is generally poor, between 5 and 7 months [15], especially if liver involvement is present [16].

Eyelids metastases are a very rare condition. Their prevalence is around 0–1% [17,18,19,20] among all eyelids malignancies. Mansour et al. [21] analyzed 31 eyelids metastases and found 35, 16, 10, and 10% of breast, skin, gastrointestinal, and urogenital cancers, respectively. Bianciotto et al. [22] studied 20 eyelids metastases and found 20, 20, 15, and 15% of skin melanoma, uveal melanoma, breast cancer, and conjunctival melanoma, respectively. Primary cancer was unknown from 7 to 45% of cases [21,22,23]. Eyelids metastases can occur very quickly (2 weeks [21]) or at distance (432 months [22]) of the primary cancer’s diagnosis (mean: 62.3 months [22]). Eyelids metastases are more often reported in women [21,22,23] reflecting the high prevalence of breast carcinoma.

Bilateral involvement, as noted in our first case, is unusual (0–10%) and very few case reports described involvement of the four eyelids [24]. Solitary nodule, as presented in both of our cases, is the most common finding (47–71%) followed by diffuse edema (6–40%), flat lesions (0–15%), ulcerative lesions (0–13%), ptosis (0–13%), and multiple nodules (0 to 5%) [21,22,23]. Interestingly, Morgan et al. [25] found that breast metastases tend to present as a diffuse edema, whereas lung metastases tend to present as a solitary nodule. The main location is the upper eyelid (35%) followed by lower eyelid (30%), lateral canthus (15%), medial canthus (10%), and multifocal (10%) [22]. Eighty five percent of metastases develop subcutaneously, 10% involve only the skin, and 5% both. The shape of the lesion is mainly sessile (80%), pedunculated (5%), or diffuse (15%) [22]. The mass is firm in 95% and soft in 5% of cases. Madarosis is not a common finding (only 35% of cases [22]) because of the subcutaneous location of the metastases.

As clinical presentation is not specific, each suspicious lesion should be biopsied, especially if cancer history is known. Pathological assessment is of main importance. It not only helps to identify the primary site of the cancer but also allows to screen new genetic mutations for further potential targeted therapies.

Prognosis is usually poor (76 and 67% survival at 6 and 12 months follow up, respectively) [22] because of generalized neoplastic spread even if no other locations have been diagnosed. Other visceral metastases are present between 73 [23] and 95% of cases [22] as presented in our two cases.

The primary goal of treatment of eyelids metastases is to maximize the quality of life and the visual field if ptosis is noted. Local treatment depends on the patient’s general health status, life expectancy, functional impairment, type (solitary nodule, diffuse edema, and etc) and size of the metastases, and the side effects of the treatment. In the cases presented herein, a palliative excision of the metastases was performed under local anesthesia with good functional result. Bianciotto et al. [22] performed surgical metastasis removal (30%), radiotherapy (35%), systemic therapy (chemotherapies) (20%), and observation alone (15%).

Conclusion

Eyelids metastases from uveal melanoma are a very rare condition. Performing their resection provides an improving of the patient’s quality of life, confirmation of the diagnosis, and identification of new genetic mutations. Prognosis is generally poor because of systemic neoplastic spread. Currently, systemic treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma is disappointing but the emergence of new targeted therapies is promising.

Study Highlights

What was known before

Eyelid metastasis from uveal melanoma is an exceptional finding.

What this study adds

Clinical, pathological and outcome of two metastatic patients.

References

Ramirez R, Ivan D, Prieto VG, Hayek B, Diwan H, Savar A, et al. Cutaneous melanoma metastatic to the eyelid and periocular skin. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:88–94.

Shields CL, Kaliki S, Cohen MN, Shields PW, Furuta M, Shields JA. Prognosis of uveal melanoma based on race in 8100 patients: the 2015 Doyne Lecture. Eye (Lond). 2015;29:1027–35.

Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. Assessment of metastatic disease status at death in 435 patients with large choroidal melanoma in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS): COMS report no. 15. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2001;119:670–6.

Singh AD, Turell ME, Topham AK. Uveal melanoma: trends in incidence, treatment, and survival. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1881–5.

Shields JA, Shields CL, Augsburger JJ, Negrey JN. Solitary metastasis of choroidal melanoma to the contralateral eyelid. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;3:9–12.

Mandaliya H, Singh N, George S, George M. Choroid melanoma metastasis to spine: a rare case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2016;2016:2732105.

Taran-Munteanu L, Hartkopf A, Eigentler TK, Vogel U, Brucker S, Taran FA. A case of choroidal melanoma metastatic to the breast. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:579–81.

Bloch-Marcotte C, Ambrosetti D, Novellas S, Caramella T, Dahman M, Thyss A, et al. Ovarian metastasis from choroidal melanoma. Clin Imaging. 2008;32:318–20.

Shields JA, Shields CL, Shakin EP, Kobetz LE. Metastasis of choroidal melanoma to the contralateral choroid, orbit, and eyelid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:456–60.

Woodman SE. Metastatic uveal melanoma: biology and emerging treatments. Cancer J Sudbury Mass. 2012;18:148–52.

Onken MD, Worley LA, Long MD, Duan S, Council ML, Bowcock AM, et al. Oncogenic mutations in GNAQ occur early in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5230–4.

Yavuzyigitoglu S, Koopmans AE, Verdijk RM, Vaarwater J, Eussen B, van Bodegom A, et al. Uveal melanomas with SF3B1 mutations: a distinct subclass associated with late-onset metastases. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1118–28.

Shields CL, Say EAT, Hasanreisoglu M, Saktanasate J, Lawson BM, Landy JE, et al. Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Uveal Melanoma Based on Tumor Features and Size in 1059 Patients: The 2016 W. Richard Green Lecture. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:609–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.12.026.

Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson EDO, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–3.

Bedikian AY, Legha SS, Mavligit G, Carrasco CH, Khorana S, Plager C, et al. Treatment of uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver: a review of the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience and prognostic factors. Cancer . 1995;76:1665–70.

Bedikian AY, Kantarjian H, Young SE, Bodey GP. Prognosis in metastatic choroidal melanoma. South Med J. 1981;74:574–7.

Aurora AL, Blodi FC. Lesions of the eyelids: a clinicopathological study. Surv Ophthalmol. 1970;15:94–104.

Arnold AC, Bullock JD, Foos RY. Metastatic eyelid carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:114–9.

Deprez M, Uffer S. Clinicopathological features of eyelid skin tumors. A retrospective study of 5504 cases and review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:256–62.

Asproudis I, Sotiropoulos G, Gartzios C, Raggos V, Papoudou-Bai A, Ntountas I, et al. Eyelid tumors at the University Eye Clinic of Ioannina, Greece: a 30-year retrospective study. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22:230–2.

Mansour AM, Hidayat AA. Metastatic eyelid disease. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:667–70.

Bianciotto C, Demirci H, Shields CL, Eagle RC, Shields JA. Metastatic tumors to the eyelid: report of 20 cases and review of the literature. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 2009;127:999–1005.

Riley FC. Metastatic tumors of the eyelids. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;69:259–64.

Martorell-Calatayud A, Requena C, Díaz-Recuero JL, Haro R, Sarasa JL, Sanmartín O, et al. Mask-like metastasis: report of 2 cases of 4 eyelid metastases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:9–14.

Morgan LW, Linberg JV, Anderson RL. Metastatic disease first presenting as eyelid tumors: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Ophthalmol. 1987;19:13–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martel, A., Oberic, A., Moulin, A. et al. Eyelids metastases from uveal melanoma: clinical and histopathologic features of two cases and literature review. Eye 33, 767–771 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-018-0317-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-018-0317-7