Abstract

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with disease progression on ibrutinib have worse outcomes compared to patients stopping ibrutinib due to toxicity. A better understanding of expected outcomes in these patients is necessary to establish a benchmark for evaluating novel agents currently available and in development. We evaluated outcomes of 144 patients with CLL treated at Mayo Clinic with 2018 iwCLL disease progression on ibrutinib. The median overall survival (OS) for the entire cohort was 25.5 months; it was 29.8 months and 8.3 months among patients with CLL progression (n = 104) and Richter transformation (n = 38), respectively. Longer OS was observed among patients with CLL progression who had received ibrutinib in the frontline compared to relapsed/refractory setting (not reached versus 28.5 months; p = 0.04), but was similar amongst patients treated with 1, 2, or ≥3 prior lines (18.5, 30.9, and 26.0 months, respectively, p = 0.24). Among patients with CLL disease progression on ibrutinib, OS was significantly longer when next-line treatment was chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (median not reached) or venetoclax-based treatment (median 29.8 months) compared to other approved treatments, such as chemoimmunotherapy, phosphoinositide 3’-kinase inhibitors, and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (9.1 months; p = 0.03). These findings suggest an unmet need for this growing patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ibrutinib has demonstrated long-term efficacy in relapsed/refractory (median progression-free survival [PFS] 44.1 months) [1] and frontline (5-year PFS estimate 70%) [2] patient populations with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), leading a therapeutic renaissance of targeted therapies capable of more frequent durable responses among even high-risk patient populations (4-year PFS among patients with TP53 alterations 79%) [3]. Despite these excellent outcomes, the majority of patients eventually discontinue ibrutinib treatment; disease progression and toxicity being the most common reasons. Patients who stop ibrutinib for disease progression have worse PFS and overall survival (OS) compared to patients who stop ibrutinib because of toxicity [4,5,6]. Alternative classes of targeted agents (e.g., BCL2 antagonists, phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors [PI3Ki], and next-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies) are now readily available in the clinic and have shown promise in the management of patients with relapsed CLL [7,8,9]. In addition, auspicious new drugs, including non-covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) such as nemtabrutinib and pirtobrutinib, are in development with preliminary studies showing impressive efficacy in relapsed CLL after ibrutinib failure [10, 11]. Finally, cellular therapies (including CAR-T and allogeneic stem cell transplant) also represent important treatment options that need to be considered for this group of high-risk patients. A better understanding of expected clinical outcomes in patients with disease progression on ibrutinib is necessary to establish a benchmark for evaluating future studies related to the actual event and options for therapy. Here, we focus on outcomes after progression on ibrutinib in a large cohort of patients with CLL, reporting survival estimates with varied treatments, line-of-therapy settings, and patterns of progression.

Methods

After IRB approval, we reviewed the medical records of patients with CLL who received ibrutinib therapy for CLL at a Mayo Clinic Cancer Center sites (Arizona, Florida, or Minnesota) between 4/2012–6/2021. Baseline relevant clinical characteristics, prior therapies, duration of ibrutinib treatment, and post-ibrutinib therapy were abstracted for all patients. Date of progression on ibrutinib therapy was ascertained by retrospective chart review and was documented according to the 2018 iwCLL guidelines [12]. Resistance mutation sequencing was conducted at NeoGenomics reference laboratory; methods are included in the Supplemental Materials.

Treatment-free survival (TFS) was analyzed as the duration from the start of treatment immediately after ibrutinib failure to the start of the subsequent line of therapy or death, whichever occurred earlier. Overall survival (OS) was analyzed as the time from date of progression while on ibrutinib and from subsequent therapy start date until date of death or last known to be alive. OS was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method (with comparisons of OS by characteristics analyzed by the log rank test) and Cox proportional hazards model. The association with OS and the event of venetoclax treatment at any time post-progression was analyzed as a time-dependent covariate in Cox proportional hazards models. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4.

Results

Patients and disease characteristics

A total of 144 patients were identified who had progression of disease on ibrutinib therapy; 106 patients had progression of CLL, whereas 38 patients developed biopsy-proven Richter transformation (35 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL], 3 with classical Hodgkin lymphoma). The characteristics of these 144 patients at the time of ibrutinib start as well as at the time of progression are shown in Table 1. The median age at the time of progression on ibrutinib was 68 years (range, 43–92). Ibrutinib was used as first-line therapy in 16% of patients. A total of 37/54 (69%) assessed patients had BTK/PLCG2 mutations identified (19 BTK mutation only; 9 PLCG2 mutation only; 9 both BTK and PLCG2 mutations); 34/45 (76%) in patients with CLL progression and 3/9 (33%) in patients who experienced Richter transformation.

Survival outcomes after progression on ibrutinib among the overall cohort

The median OS of the entire cohort after progression on ibrutinib was 25.5 months (95% CI 17.7-31.0). Not unexpectedly, the OS was significantly different between those who experienced CLL disease progression versus Richter transformation (median 29.8 versus 8.3 months, respectively; p = 0.002, Fig. 1). The median OS of patients who experienced CLL disease progression when ibrutinib was used in the first-line setting was longer compared to those treated in the relapsed/refractory setting (not reached versus 28.5 months; p = 0.04; Fig. 2A). The median follow-up of patients from time of progression was 16.6 months overall; 23.5 months among patients treated in the first-line setting and 15.9 months in the relapsed/refractory setting. Among patients treated in the relapsed/refractory setting, the median OS when ibrutinib was used after one prior line (n = 20), 2 prior lines (n = 29), or ≥3 prior lines (n = 40) was 18.5, 30.9, and 26.0 months, respectively (p = 0.24; Fig. 2B). Similar rates of venetoclax-based treatment as immediate next-line therapy were used amongst these three groups (1 prior line, 2 prior lines, ≥3 prior lines): 60%, 45%, and 50%, respectively. The median OS of patients who experienced Richter transformation based on whether ibrutinib was used as first-line CLL therapy (n = 6) or in the relapsed/refractory setting (n = 32) was 7.3 versus 9.0 months (p = 0.69; Fig. 3A). Similarly, the median OS of patients who experienced diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) transformation was not significantly different whether ibrutinib was used as first-line therapy (n = 5) or in the relapsed/refractory setting (n = 30) (8.1 versus 7.3 months, respectively; p = 0.91; Fig. 3B).

A It compares overall survival between all patients who experienced Richter transformation (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or Hodgkin lymphoma) while receiving firstline ibrutinib to those in the relapsed/refractory setting. B It considers only patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma Richter transformation events.

Clinical presentation and outcomes in patients with CLL progression

Heterogenous patterns of progression were observed: progressive lymphadenopathy without concurrent lymphocytosis (n = 44); progressive lymphocytosis without concurrent lymphadenopathy (n = 39); concurrent progressive lymphadenopathy and lymphocytosis (n = 18). Progression without lymphadenopathy or lymphocytosis (i.e., biopsy-proven marrow infiltration causing cytopenias, progressive hepatosplenomegaly) was seen in only five patients. Presentation of progression was associated with OS with a trend towards a difference in TFS (Fig. 4A, B). The median OS from time of progression on ibrutinib was 17.7 months (95% CI, 10.5–40.6 months) among patients with lymphadenopathy without lymphocytosis, 22.6 months (95% CI, 15.9—not estimable) among patients with lymphadenopathy and lymphocytosis, and 46.7 months (95% CI, 31.0-not estimable) among patients with lymphocytosis without lymphadenopathy (p = 0.012). TP53 disruption was not associated with pattern of progression (p = 0.86).

A It compares overall survival by pattern of progression: lymphocytosis without lymphadenopathy, lymphadenopathy without lymphocytosis, or lymphocytosis and lymphadenopathy. B It compares treatment-free survival between the same groups. Note, the five patients with iwCLL-defined disease progression but without lymphadenopathy or lymphocytosis (i.e., biopsy-proven marrow infiltration causing cytopenias, progressive hepatosplenomegaly) are not included in this analysis.

Treatment outcomes in patients with CLL progressive disease

Among all patients with CLL progression (n = 106), the median time from iwCLL-defined progression to start of subsequent therapy was 1.4 months (95% CI, 1.0–1.8 months; range 0.1–23.5 months). The most common first salvage therapy consisted of a venetoclax-based regimen n = 56, PI3Ki-based treatment n = 11, chemoimmunotherapy n = 11, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR T) n = 6, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment n = 4, and other therapies (comprised of various clinical trials) n = 6. Seven patients died before any salvage therapy could be administered because of progressive disease. Five patients continued ibrutinib therapy (±anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) despite iwCLL progression for a median of 12.9 months (range 2.1–23.5 months).

The median OS was significantly longer among patients treated with CAR T or venetoclax-containing regimens compared to other approved treatments (e.g., chemoimmunotherapy, PI3Ki-based, and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) at not reached, 29.8 months, and 9.1 months, respectively (p = 0.034; Fig. 5A). The median TFS was also significantly longer in patients receiving CAR T or venetoclax-based regimens compared to other approved treatments at 30.4 months, 20.1 months, and 4.4 months, respectively (p < 0.001; Fig. 5B). Additional OS and TFS analyses of patients divided into smaller treatment subgroups are shown in the Supplemental Materials. Patients who started post-ibrutinib salvage treatment before April 2016 (approval date of venetoclax for relapsed CLL in the U.S.) had shorter OS (median 2.6 versus 31.0 months; P = 0.005). However, receipt of venetoclax treatment any time following progression on ibrutinib (e.g., not only as immediate next therapy) was not associated with better OS (HR 1.0, 95% CI 0.6–1.6; p = 0.89). Among the 56 patients who received venetoclax-based first subsequent therapy, 38 patients received venetoclax (±anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) and 18 patients received venetoclax plus continued ibrutinib (±anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody). Patients who continued ibrutinib with venetoclax-based treatment had similar TFS to those who did not continue ibrutinib (median 23.7 versus 16.7 months; p = 0.26; Fig. 6). TP53 disruption was not associated with TFS (HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.7–2.1; p = 0.51).

In univariate analyses, IGHV mutation status, TP53 disruption, and the presence of a BTK or PLCG2 mutation status were not predictors of shorter OS from time of CLL disease progression on ibrutinib. Time from iwCLL progression to start of subsequent therapy ≥1.5 months versus <1.5 months was associated with longer OS from subsequent therapy (47.1 versus 25.6 months; p = 0.03).

Treatment outcomes in patients with Richter transformation

Among the 35 patients who had transformation to DLBCL, the most common first salvage therapy consisted of chemoimmunotherapy in 15 patients, immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in nine patients, venetoclax-based therapy in three patients, and PI3Ki-based treatment, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment, and antibody drug conjugate treatment in two patients each. Two patients died before any salvage therapy could be administered because of progressive disease. The OS and TFS of these patients according to the types of treatments administered is shown in Supplemental Figs. 2A and 2B, respectively. Type of treatment did not have a significant impact on OS nor TFS.

Among the three patients who had transformation to Hodgkin lymphoma, two remained alive at last follow-up >4 years after receipt of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) with no relapse of Hodgkin lymphoma. One patient died amidst neutropenic infection while in a partial remission after treatment with BCVPP (carmustine, vinblastine, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, prednisone).

Discussion

Here, we report on a meaningfully large cohort of nearly 150 patients showing a median overall survival of 25.5 months from the time of iwCLL progression on ibrutinib. This is strikingly similar to that reported in a recent abstract from The Ohio State University group on a similar cohort (median 24.4 months) [13]. Outcomes beyond CLL progression on ibrutinib were similar among those treated in the relapsed/refractory setting irrespective of number of prior lines, but differed by immediate subsequent therapy, favoring venetoclax-based and CAR T treatments. Key clinical observations at the time of progression, including pattern of progression and time from progression to next therapy start, also showed prognostic OS relevance in our study. These data improve our current understanding of outcomes in this growing patient population and provide a critical benchmark when considering trials of promising novel agents in development. Treatment patterns and outcomes following disease progression on a BTKi among CLL patients are less well represented in the randomized, prospective clinical trials of approved treatments in the relapsed/refractory space [7, 8]. Extrapolating predictions for patients with ibrutinib-refractory disease from data in ibrutinib-exposed patients is problematic and therapeutic decisions are guided by single-arm prospective studies, subgroup analyses, and limited retrospective cohorts.

Previous studies have shown a limited benefit to be expected with PI3Ki or chemoimmunotherapy (median PFS 9 months and 5.1 months, respectively) in patients who previously received ibrutinib and stopped for any reason [14]. Our study demonstrates patients with CLL disease progression on ibrutinib have better survival outcomes with venetoclax-based regimens compared to other approved options (median OS 29.8 versus 9.1 months; median TFS 20.1 versus 4.4 months). In the prospective study of venetoclax monotherapy post-BTKi treatment, the median PFS was 24.7 months and 12-month OS rate 91%, without separating that cohort by exposed and refractory subgroups. Overall response was higher among patients non-refractory to prior BTKi treatment (63% versus 54%) [15]. A pooled analysis of these patients and others treated with venetoclax on a clinical trial post-BTKi reported an ORR of ~65% without differentiating BTKi-exposed versus –refractory [16]. In our cohort, venetoclax at any time post-ibrutinib progression did not impart the same OS benefit observed when analyzing next-line venetoclax compared to alternative options. While difficult to reconcile these findings entirely, comparing outcomes pre- and post-venetoclax approval date also hints at an importance in sequence of therapies. Altogether, our new results and these previously reported data support the most common current practice of proceeding to venetoclax-based treatment as next-line treatment following progression on ibrutinib in venetoclax-naïve patients. CAR T also has therapeutic efficacy in highly refractory patients but lacks current approval [17]. Patients treated with CAR T in our cohort had outstanding outcomes (illustrated by a median OS not reached with no events among the six patients), but conclusions are precluded by the limited number of patients and the optimal timing to pursue cellular therapy in the novel agent era remains unknown.

Considering the risk for disease flare with ibrutinib interruption, particularly amidst progressive disease, the synergistic combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax has appeal in the post-ibrutinib progression setting as well [18]. However, when focusing on the venetoclax-based treatment subgroups in this study, no significant difference in TFS was observed with continued ibrutinib. Results have not yet been reported for a prospective trial (NCT03422393) evaluating dose-escalated ibrutinib and the addition of venetoclax for next-line treatment at ibrutinib progression.

We demonstrated the pattern of progression, specifically progressive lymphadenopathy, was associated with post-progression OS. Median survival estimates among the pattern of progression subgroups (17.7 months and 46.7 months for patients with lymphadenopathy without lymphocytosis and lymphocytosis without lymphadenopathy, respectively) closely resembled those presented by the OSU group (15.2 months and 49.9 months for the same groups) [13]. Better understanding this difference is an area of active research. A possible contribution could be differing mechanisms of resistance. Resistance mutations in BTK and PLGC2 were less frequently detected among patients relapsing with lymphadenopathy (40%) compared to those with lymphocytosis (81%) in a prior study [19]. Another potential reflection of varied CLL biology at relapse on ibrutinib is our finding that patients who received subsequent treatment ≥1.5 months beyond relapse had OS that was approximately twice as long as patients receiving next-line therapy sooner. One possible reason for this apparent paradox is that the patients progressing in a more gradual, less dramatic fashion and thus in less need of urgent change in therapy are biased to more favorable outcomes, similar to the diagnosis-to-treatment interval shown in patients with newly diagnosed large cell lymphoma [20].

Survival following Richter transformation to DLBCL on ibrutinib was similarly dismal whether occurring in the frontline or relapsed/refractory setting, emphasizing the continuing urgent need for better Richter transformation treatments. Outcomes differed between frontline and relapsed settings in those with CLL progression with longer survival observed following progression on frontline ibrutinib. Unexpectedly, among patients who received ibrutinib in the relapsed setting, post-progression survival was similar across patients with one to three or more prior lines of therapy. This finding seems to place emphasis on treatment after progression on ibrutinib but requires validation in independent cohorts.

The majority of ibrutinib treatment in this study occurred in the relapsed/refractory setting, which may be less reflective of contemporary practice and is a limitation of the study. Our experience here is that of a tertiary referral center, which likely explains the higher-than-expected number of Richter transformation cases observed and should not be interpreted as a true incidence rate. Exploring the impact of resistance mutations in outcomes and patterns of progression is limited due to lack of consistent sequencing in this cohort. Similarly, the limitation of non-uniform follow-up inherent to a retrospective study precludes reporting a reliable response assessment. However, strengths include (1) our focus on meaningful TFS and OS outcomes; (2) description of clinical features of the disease progression while on ibrutinib made possible by a well-annotated, prospectively maintained CLL Database; (3) relatively long follow-up compared to earlier studies evaluating this patient population. These aspects of the study facilitate providing greater insight overall into outcomes of CLL patients in the post-ibrutinib progression period.

Results from this study demonstrate that progression of disease on ibrutinib represents an ongoing unmet need in patients with CLL. Although non-covalent BTKi, such as nemtabrutinib and pirtobrutinib, show promising efficacy in this setting, they currently lack label approval and are only available through a clinical trial [10, 11]. Participation in well-designed clinical trials is remains key for this growing patient population. Venetoclax-based treatments (if not given before) are the current standard in the clinic for this group and indeed offered amongst the best TFS and OS outcomes in this study. We speculate that the role for continued ibrutinib beyond progression in combination with venetoclax in certain patients and the impact and optimal timing of cellular therapy remain important questions.

Data availability

Data not available without request and IRB review due to patient confidentiality.

References

Munir T, Brown JR, O’Brien S, Barrientos JC, Barr PM, Reddy NM, et al. Final analysis from RESONATE: up to 6 years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:1353–63.

Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Ghia P, Tedeschi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia 2020;34:787–98.

Allan JN, Shanafelt T, Wiestner A, Moreno C, O’Brien SM, Li J, et al. Long-term efficacy of first-line ibrutinib treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in patients with TP53 aberrations: a pooled analysis from four clinical trials. Br J Haematol. 2022;196:947–53.

Hampel PJ, Ding W, Call TG, Rabe KG, Kenderian SS, Witzig TE, et al. Rapid disease progression following discontinuation of ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated in routine clinical practice. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60:2712–9.

Jain P, Thompson PA, Keating M, Estrov Z, Ferrajoli A, Jain N, et al. Long-term outcomes for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who discontinue ibrutinib. Cancer 2017;123:2268–73.

Mato AR, Thompson M, Allan JN, Brander DM, Pagel JM, Ujjani CS, et al. Real-world outcomes and management strategies for venetoclax-treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in the United States. Haematologica 2018;103:1511–7.

Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, Hillmen P, D’Rozario J, Assouline S, et al. Venetoclax–rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl J Med. 2018;378:1107–20.

Sharman JP, Coutre SE, Furman RR, Cheson BD, Pagel JM, Hillmen P, et al. Final results of a randomized, phase III study of rituximab with or without Idelalisib followed by open-label idelalisib in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1391–402.

Lunning M, Vose J, Nastoupil L, Fowler N, Burger JA, Wierda WG, et al. Ublituximab and umbralisib in relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2019;134:1811–20.

Mato AR, Shah NN, Jurczak W, Cheah CY, Pagel JM, Woyach JA, et al. Pirtobrutinib in relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies (BRUIN): a phase 1/2 study. Lancet 2021;397:892–901.

Woyach JA, Flinn IW, Awan FT, Eradat H, Brander DM, Tees M, et al. Preliminary efficacy and safety of MK-1026, a non-covalent inhibitor of wild-type and C481S mutated Bruton Tyrosine kinase, in B-cell malignancies: a phase 2 dose expansion study. Blood 2021;138:392.

Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood 2018;131:2745–60.

Kittai AS, Huang Y, Keiter A, Beckwith KA, Goldstein D, Bhat SA, et al. Utilizing clinical features of progression to predict richter’s syndrome in patients with CLL progressing after ibrutinib. Blood 2021;138:3731.

Mato AR, Hill BT, Lamanna N, Barr PM, Ujjani CS, Brander DM, et al. Optimal sequencing of ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a multicenter study of 683 patients. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1050–6.

Jones JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, Davids MS, Choi M, Cheson BD, et al. Venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia progressing after ibrutinib: an interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:65–75.

Roberts AW, Ma S, Kipps TJ, Coutre SE, Davids MS, Eichhorst B, et al. Efficacy of venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia is influenced by disease and response variables. Blood 2019;134:111–22.

Siddiqi T, Soumerai JD, Dorritie KA, Stephens DM, Riedell PA, Arnason JE, et al. Phase 1 TRANSCEND CLL 004 study of lisocabtagene maraleucel in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL or SLL. Blood. 2022;139:1794–1806.

Hampel PJ, Call TG, Rabe KG, Ding W, Muchtar E, Kenderian SS, et al. Disease flare during temporary interruption of ibrutinib therapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncologist. 2020;25:974–80.

Wiestner A, Ghia P, Byrd JC, Ahn IE, Moreno C, O’Brien SM, et al. Rarity of B-cell receptor pathway mutations in progression-free patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) during first-line versus Relapsed/Refractory (R/R) treatment with ibrutinib. Blood 2020;136:32–3.

Maurer MJ, Ghesquières H, Link BK, Jais JP, Habermann TM, Thompson CA, et al. Diagnosis-to-treatment interval is an important clinical factor in newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and has implication for Bias in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1603–10.

Acknowledgements

The conduct of this research was supported in part by the Henry J. Predolin Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PJH, KGR, and SAP designed the research, collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; TGC, WD, JFL, AAC-K, SSK, EM, YW, SA, ABK, RP, TS, CAH, MS, DLVD, EB, and NEK cared for the patients, interpreted the results, and critically reviewed/revised the manuscript; SMS acquired data and critically reviewed/resvied the manuscript; SLS and KGR analyzed data, conducted statistical analyses, and critically reviewed/revised the manuscript; all authors approved the manuscript in its final format.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests in direct relation to the work reported. The following authors also declare no competing financial interests otherwise: PJH, KGR, TGC, JFL, RP, SMS, TS, CAH, MS, DLVD, EB, SLS,. In the interest of transparency, additional potential conflicts of interest for the remaining authors are included subsequently. WD: Research funding has been provided to the institution from Merck and DTRM. Participation in advisory board meetings for Merck and Octapharma. AAC-K: Consultancy for BieGene, Janssen, and Ascentage. Equity holder in Cellectar. Stock options in Alpha2 Pharmaceuticals, NonoDev, Starton. Research funding from Ascentage. Patents and royalties in Alpha2 Pharmaceuticals. Membership on Board of Directors or advisory committees for Acentage, Starton, Cellectar, NonoDev, and Alpha2 Pharmaceuticals. Honoraria from BeiGene, Janssen, Acentage. SSK: Consultancy, honoraria, and research funding from Humanigen, Inc. EM: Honorarium from Janssen. Consultation fee from Protego (paid to the institution). YW: Membership on Board of Directors or advisory committies for Incyte, LOXO Oncology, Eli Lilly, TG Therapeutics. Research funding from Incyte, InnoCare, LOXO Oncology, Novartis, Genentech, MorphoSys. SA: Consultancy for BMS, Janssen, Amgen, Pharmacyclics, GSK, Takeda, Genentech, AbbVie, Karyopharm, Beigene, Sanofi. Research funding from BMS, Janssen, Amgen, Pharmacyclics, Ascentage, Medimmune, Cellectar, Xencor, GSK. ABK: Membership on Board of Directors or advisory committees for AbbVie and TG Therapeutics. NEK: Membership on Board of Directors or advisory committees for Abbvie, BMS, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, AstraZeneca, Behring, CytomX Therapeutics, Dava Oncology, Janssen, Juno Therapeutics, Oncotracker, Targeted Oncology, Agios Pharm, MorphoSys, Rigel. Research funding from Abbvie, Acerta Pharma, BMS, Celgene, Genentech, MEI Pharma, Sunesis, TG Therapeutics, Tolero Pharmaceuticals. SAP: Research funding has been provided to the institution from Pharmacyclics, Janssen, AstraZeneca, TG Therapeutics, Merck, AbbVie, and Ascentage Pharma for clinical studies in which SAP is a principal investigator. SAP has received honoraria for participation in consulting activities/advisory board meetings for Pharmacyclics, Merck, AstraZeneca, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, and AbbVie (no personal compensation); and from DynaMed, Aptitude Health, Curio Science, and MedEd on the Go (with personal compensation).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hampel, P.J., Rabe, K.G., Call, T.G. et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with disease progression on ibrutinib. Blood Cancer J. 12, 124 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-022-00721-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-022-00721-6

This article is cited by

-

Richter Transformation of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia—Are We Making Progress?

Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports (2023)

-

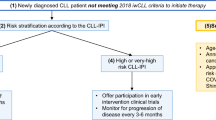

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment algorithm 2022

Blood Cancer Journal (2022)