Abstract

Introduction

We present a case of a previously asymptomatic and highly functional individual whose critical degenerative stenosis was exacerbated by recent trauma (motor vehicle accident), resulting in cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old African-American man with no significant past medical history presented to the Orthopaedic Surgery outpatient clinic with mild neck discomfort, stiffness, and bilateral hand numbness 4 days after being involved in a motor vehicle accident. He ambulated without assistive devices and displayed a tandem gait pattern with normal cadence. He was minimally tender to palpation at the posterior cervical midline and paraspinal musculature with motor and sensory function intact bilaterally. Reflexes were hypoactive at C5, C6, C7, L4, and S1 bilaterally with positive Babinski signs bilaterally. Imaging revealed degenerative changes, spinal stenosis, and cord compression. The patient eventually underwent posterior cervical decompression and fusion from the C3 to the C6 level, with the only reported complication being transient loss of somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) signals intra-operatively. In the postoperative period, the patient complained of stiffness in his left shoulder, elbow, and hand, as well as left hand palmar numbness and an inability to make a full fist. His complaints were managed with medication and physical therapy.

Discussion

This case report highlights the point that stenosis that occurs slowly over time is often well compensated, and patients are commonly asymptomatic at first glance. Often times, acute events tip patients from being asymptomatic to symptomatic, generally warranting invasive intervention to prevent further insults from causing permanent damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical myelopathy is defined as cervical spinal cord compression resulting in development of upper motor neuron symptoms. Dysfunction generally progresses in a stepwise pattern with intermittent exacerbations [1,2,3,4,5]. The molecular basis for neuronal dysfunction has been linked to Fas-mediated apoptosis of neurons and oligodendrocytes, and is associated with activation of caspase 3 8 and 9. Physical examination findings include atrophy, motor, and sensory deficits, upper motor neuron dysfunction, or gait disturbances [6, 7]. The subaxial cervical spinal canal has a diameter of 17–18 aboutmm, with the spinal cord occupying ~10 mm. When canal diameter falls below 12 mm, with or without a Pavlov ratio less than 0.8 on lateral radiographs or an abnormal anteroposterior compression ratio, the likelihood of myelopathy increases [8,9,10].

Conservative treatment is indicated in the absence of severe clinical findings. Operative interventions, including anterior cervical discectomy or corpectomy and fusion, posterior cervical discectomy and fusion, laminectomy, laminoplasty, or a combined approach, are indicated in patients with significant functional impairment with one to two-level disease or deformity [11]. The decision to use an anterior or posterior approach should be an individualized one based on the mechanism and location of pathology, with multiple recent studies noting similar efficacies [12, 13].

We present a rare case of a previously asymptomatic and highly functional individual whose critical degenerative stenosis was exacerbated by trauma and surgical intervention.

Case presentation

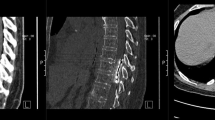

A 57-year-old African American man presented to the outpatient clinic with mild neck discomfort, stiffness, and bilateral volar index and long finger numbness and tingling 4 days after involvement in a motor vehicle accident as a restrained driver. Physical examination revealed 5/5 strength bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities along with hypoactive reflexes at C5-C7, L4, and S1 and presence of Hoffman’s signs (flexion of thumb or index finger with flicking of the nail of the ipsilateral middle finger suggesting cervical spinal cord compression) bilaterally. CT scan of the cervical spine (Fig. 1) without contrast showed severe spondylosis, including marked stenosis of the spinal canal, cord compression, a markedly enlarged left styloid process compatible with a variant of Eagle syndrome (symptomatic elongation of the styloid process or calcified stylohyoid ligament that can cause compression of cranial nerves or carotid artery), and multiple osteophytic changes [14]. The vertebral body to canal ratio ranged from 1.47 to 2.36 at C3–C7 [15]. Cervical lordosis was preserved with a lack of endplate changes or any anterior-to-posterior translation.

MRI (Fig. 2) showed a canal narrowed to 1.88 mm and commensurate compression at C3–C4, broad-based disc and ligamentous redundancy, narrowing of the canal at the C4–C5 level (5.16 mm) with cord flattening, and bilateral myelomalacia. Additionally, minor canal stenosis (6.17 mm) with significant left foraminal stenosis at C5–C6 was reported.

At the 3-month follow-up, patient continued to have 5/5 strength bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities with no bladder or bowel dysfunction. The patient underwent posterior cervical decompression and fusion from C3 to C6 3 months later (6 months after injury). A transient loss of somatosensory evoked potential signals was noted intraoperatively, which was treated with intravenous Decadron and maintenance of mean arterial pressures (MAP) at 90 mmHg. At 6 months post operation, he noted continued neck stiffness and left arm pain that radiated from his neck, left hand palmar numbness, and an inability to make a full fist. He demonstrated 4/5 strength in the C5–T1 distributions bilaterally, except grip strength on the left (3/5) with slow ambulation without assistive devices. A follow-up MRI (Fig. 3) revealed adequate cord decompression with stable instrumentation. Subsequently, the patient underwent extensive postoperative physical rehabilitation centering on strengthening and dexterity of the upper extremities.

Discussion

This is a case of a whiplash-type injury exacerbating pre-existing multilevel stenosis resulting in clinical myelopathy. The presence of myelomalacia instead of edema, osteophytes, and degenerative changes on MRI point to long-standing subclinical multilevel stenosis. A severely decompressed spinal cord can take on a teardrop or banana shape, eventually deforming into a triangular shape. In these patients, T2-weighted images on MRI exhibit changes more frequently than T1- weighted images. However, T1 signal changes carry a much-poorer prognosis than T2 changes, almost always being associated with symptomatic compression [16].

Despite this injury, which can be described as an International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISCOS) total motor score of 50 and a total sensory score of 112, an American Spine Injury Association D, Nurick Grade I, a normal Japanese Orthopaedic Association score [16,17,18,19], this patient’s body had compensated (despited falling below the 12 mm cutoff for increased myelopathic symptoms [8]), allowing the neural circuit to normally function with only minor symptoms. However, the severity of his damage is an indication for surgical decompression and fusion. The decision was made to solely use a posterior approach, due to multi-level pathology causing stenosis and the complications involved with an anterior cervical approach including dysphagia, retropharyngeal hematoma, other respiratory complications, and damage to surrounding nerves and vessels. However, the authors realize that a combined anterior and posterior approach was a possibility given the location of this patient's pathology. The patient’s increase in pain and upper extremity weakness following adequate decompression was thought to be related to intraoperative loss of neuromonotoring signals or a transient reperfusion injury at the levels of critical stenosis.

This case highlights that stenosis which occurs slowly over time is often well compensated, and patients are commonly asymptomatic at first. Nevertheless, acute events can tip patients from being asymptomatic to symptomatic, generally warranting invasive intervention to help halt disease progression. However, surgical intervention does not always relieve these symptoms, sometimes even making symptoms worse. One must critically consider on a case-by-case basis whether surgical intervention, the treatment choice that is typically used in these situations, is necessary or beneficial, as has been suggested in recent articles [20, 21]. As suggested by this patient's clinical course, observation is a valid treatment option in minimally symptomatic patients [22,23,24], and surgical intervention may not be benign even in well-trained hands.

References

Payne EE, Spillane JD. The cervical spine an anatomico-pathological study of 70 specimens (using a special technique) with particular reference to the problem of cervical spondylosis. Brain. 2002;80:571–96.

Brain WR, Northfield D, Wilkinson M. The neurological manifestations of cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1952;75:187–225.

Clarke E, Robinson PK. Cervical myelopathy: a complication of cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1956;79:483–510.

Lees F, Turner JA. Natural history and prognosis of cervical spondylosis. Br Med J. 1962;2:1607.

Yu WR, Baptiste DC, Liu T, Odrobina E, Stanisz GJ, Fehlings MG. Molecular mechanisms of spinal cord dysfunction and cell death in the spinal hyperostotic mouse: implications for the pathophysiology of human cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:149–63.

Chikuda H, Seichi A, Takeshita K, Shoda N, Ono T, Matsudaira K, et al. Correlation between pyramidal signs and the severity of cervical myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1684–9.

Emery SE. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:376–88.

Coughlin TA, Klezi Z. Cervical Myelopathy. Bone & Joint. 2015. http://www.boneandjoint.org.uk/content/focus/cervical-myelopathy.

Costa F, Tomei M, Sassi M, Cardia A, Ortolina A, Servello D, et al. Evaluation of the rate of decompression in anterior cervical corpectomy using an intra-operative computerized tomography scan (O-Arm system). Eur Spine J. 2012;21:359–63.

Ogino H, Tada K, Okada K, Yonenobu K, Yamamoto T, Ono K. Canal diameter, anteroposterior compression ratio, and spondylotic myelopathy of the cervical spine. Spine. 1983;8:1–15.

Yoon ST, Hashimoto RE, Raich A, Shaffrey CI, Rhee JM, Riew KD. Outcomes after laminoplasty compared with laminectomy and fusion in patients with cervical myelopathy: a systematic review. Spine. 2013;38:S183–94.

Lawrence BD, Jacobs WB, Norvell DC, Hermsmeyer JT, Chapman JR, Brodke DS. Anterior versus posterior approach for treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a systematic review. Spine. 2013;38:S173–82.

Fehlings MG, Barry S, Kopjar B, Yoon ST, Arnold P, Massicotte EM, et al. Anterior versus posterior surgical approaches to treat cervical spondylotic myelopathy: outcomes of the prospective multicenter AOSpine North America CSM study in 264 patients. Spine. 2013;38:2247–52.

Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with Eagle syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1401–2.

Suk KS, Kim KT, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim JS, Kim JY. Reevaluation of the Pavlov ratio in patients with cervical myelopathy. Clin Orthop Surg. 2009;1:6–10.

Benzel EC. Pain and neural dysfunction in cervical degenerative disease. In: The cervical spine. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. p. 911.

Sabharwal S. Spinal cord injury (cervical). In: Frontera WR, Silver JK, Rizzo TD, editors. Essentials of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 3rd edn. Elsevier Health Sciences; Pennsylvania, United States 2014.

Guha A, Tator CH, Endrenyi L, Piper I. Decompression of the spinal cord improves recovery after acute experimental spinal cord compression injury. Spinal Cord. 1987;25:324–39.

Sandler AN, Tator CH. Effect of acute spinal cord compression injury on regional spinal cord blood flow in primates. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:660–76.

Kaye ID, Vaccaro AR. The case for surgery of the injured spine in the management of traumatic cord injuries. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2018;4:15.

El WM. Traumatic spinal injury and spinal cord injury: point for active physiological conservative management as compared to surgical management. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2018;4:14.

Bridges J, Sandoval R. Clinical outcomes following conservative management of chronic traumatic cervical myelopathy: a case report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;34:231–40.

Rhee J, Tetreault LA, Chapman JR, Wilson JR, Smith JS, Martin AR. et al. Nonoperative versus operative management for the treatment degenerative cervical myelopathy: an updated systematic review. Glob Spine J. 2017;7:S35–41.

Koyanagi I. Options of management of the patient with mild degenerative cervical myelopathy. Neurosurg ClinN Am. 2018;29:139–44.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

IRB Approval

IRB approval was obtained from the St. Luke’s University Health Network IRB Committee.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gangavalli, A.K., Malige, A. & Sokunbi, G. Multilevel critical stenosis with minimal functional deficits: a case of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 4, 104 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0138-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0138-8