Abstract

Introduction

Spinal epidural lipomatosis (SEL) involves hypertrophy of fat tissue in the extradural space, often associated with long-term corticosteroid therapy. Sometimes it causes severe spinal cord compression and the patient gradually becomes symptomatic. However, sudden onset of neurological deterioration is extremely rare.

Case presentation

We herein present a case of sudden paraplegia in a patient with thoracic SEL at 2 months after thoracic vertebral fracture, whose symptoms were consistent with a lesion at the same level as the SEL. Computed tomography scan showed no remarkable change in the degree of vertebral fracture at the time of neurological deterioration. We performed immediate decompression surgery and found hemorrhage and granulation tissue at the level of the fracture and removed it with the epidural fat tissue. The hematoma and granulation tissue were thought to be the cause of the acute deterioration. The patient recovered gradually from the paraplegia.

Discussion

Sudden paraplegia with SEL at the time of vertebral fracture has previously been reported, but this is the first report of SEL with delayed onset of paraplegia after an initial diagnosis of coexisting vertebral fracture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal epidural lipomatosis (SEL) involves hypertrophy of fat tissue in the extradural space and is often associated with long-term corticosteroid therapy. Sometimes it causes severe spinal cord compression and the patient gradually becomes symptomatic [1]. However, sudden onset of neurological deterioration is extremely rare [2]. We herein present a case of sudden paraplegia in a patient with thoracic SEL at 2 months after thoracic vertebral fracture, whose symptoms were consistent with a lesion at the same level as the SEL.

Case presentation

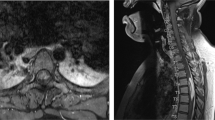

A 66-year-old man presented with back pain. He had a history of colon cancer and multiple lung metastases. He also had a very long history of taking oral prednisolone (10 mg daily for 30 years) prescribed by his primary care doctor for severe chronic urticaria (provoked by contact with metal). On admission, he had severe back pain localized to his mid-back. On examination, he showed no motor weakness and had no sensory disturbance in his lower extremities. X-ray images of the thoracic spine revealed a vertebral compression fracture at T6. There was no posterior wall fracture. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated no signs of vertebral metastasis, but it also revealed the presence of SEL at the same level as the fracture (Fig. 1).

We diagnosed vertebral compression fracture due to glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Our treatment plan included immobilization and oral analgesics. After that, the pain resolved gradually, and he had no impairment in his daily activities. However, 2 months after the first visit, he experienced sudden onset of paraplegia in his lower extremities without any specific trigger event. He was transported to our emergency department. According to the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury, his total motor score of the lower limb was 0, and only little sensation was preserved at the S4–5 level. His neurological classification was AIS B. These exams were performed by the same assessor.

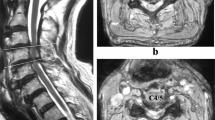

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed no worsening of the vertebral body fracture (Fig. 2a). Immediate MRI scan showed emerging abnormal tissue around the spinal cord at T6 (Fig. 2b). At this point, we considered infection or metastatic tumor extension to be the cause of the acute deterioration, though a definitive diagnosis could not be made by imaging findings.

Imaging studies at time of neurological deterioration. a Computed tomography images of the thoracic spine show no posterior wall protrusion. b Magnetic resonance images of thoracic spine show cerebrospinal fluid within the epidural space has slightly diminished, but there is no obvious new emergence of a tumor or abscess

He underwent emergency surgery. After posterior laminectomy from T5 to T7, epidural fat tissue was exposed, which looked like normal tissue. After removal of this fat tissue, granulation tissue around the dural sac was seen at T6. We also removed the granulation tissue so that decompression of the spinal cord was accomplished. Pathological findings revealed that the tissue consisted of hemorrhagic material and granulation tissue. After surgery, the neurological findings in his lower extremities gradually recovered, and he was able to actively move his leg. Postoperative MRI showed that decompression of the spinal cord had been accomplished, but slight degeneration of the cord remained (Fig. 3). He was then moved to a rehabilitation institution and underwent functional training. Three months after surgery, he was able to walk with an ankle-foot orthosis and double crutch.

Discussion

We report a patient who experienced delayed neurological deterioration as a result of SEL that progressed after the onset of vertebral fracture. SEL involves hypertrophy of fat tissue in the extradural space and is often associated with long-term corticosteroid therapy. Sometimes it causes severe spinal cord compression, but usually the symptoms develop gradually; acute worsening of neurological deterioration is very rare. Two cases of idiopathic SEL [2, 3] and one case complicated by epidural abscess [4] have previously been reported. One other case of simultaneous sudden paraplegia and vertebral compression fracture due to SEL, similar to our case, has also been reported [5]. However, in our case, paraplegia emerged 2 months after the fracture, and no worsening of the vertebral fracture was observed on CT at the time of neurological deterioration. We could not find any determinate cause of deterioration preoperatively, but intraoperative findings revealed that hematoma and granulation tissue caused the spinal cord injury.

Most traumatic spinal cord injury occurs at the time of a traumatic event, but a previous report showed that delayed neurological deficits could occur several weeks after thoracic compression fracture due to epidural hematoma [6]. In our case, we could not identify the hematoma before the operation because it was too small. Usually such a small hematoma would not be the cause of a spinal cord injury, but in our case the coexistence of SEL at the level of the fracture became the determinant factor related to symptom eruption. In addition, our case was remarkable in that the patient had a very long history of corticosteroid use. This likely provoked both the development of SEL [1] and the vertebral compression fracture [7], finally resulting in spinal cord injury.

Moreover, asymptomatic SEL is not usually treated surgically. However, our case suggests that we must carefully follow neurological examinations and monitor for acute deterioration in patients with SEL, especially if a coexisting vertebral compression fracture has occurred.

Conclusion

We report the first case of SEL with delayed-onset paraplegia after an initial diagnosis of coexisting vertebral fracture. Even slight hematoma formation can cause spinal cord injury in patients with SEL, and immediate decompression surgery may be necessary.

References

Al-Khawaja D, Seex K, Eslick GD. Spinal epidural lipomatosis—a brief review. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:1323–6.

Meisheri YV, Mehta S, Chattopadhyay K. Acute paraplegia due to an extradural spinal lipoma: case report. Spinal Cord. 1996;34:633–4.

Lopez-Gonzalez A, Resurreccion Giner M. Idiopathic spinal epidural lipomatosis: urgent decompression in an atypical case. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:S225–7.

Zuccoli G, Pipitone N, De Carli N, Vecchia L, Bartoletti SC. Acute spinal cord compression due to epidural lipomatosis complicated by an abscess: magnetic resonance and pathology findings. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:S216–9.

Celik SE, Erer SB, Gulec I, Gokcan R, Naderi S. Sudden paraplegia following epidural lipomatosis and thoracal compression fracture after long-term steroid therapy: a case report. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:1227–9.

Kang MS, Shin YH, Lee CD, Lee SH. Delayed neurological deficits induced by an epidural hematoma associated with a thoracic osteoporotic compression fracture. Neurol Med Chir. 2012;52:633–6.

Allen CS, Yeung JH, Vandermeer B, Homik J. Bisphosphonates for steroid-induced osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:Cd001347.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for publication of this case was obtained from the patient.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shurei, S., Yamakawa, K., Hozumi, T. et al. Occurrence of sudden paraplegia during follow-up period of thoracic vertebral compression fracture in a case with spinal epidural lipomatosis. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 3, 17075 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-017-0001-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-017-0001-3