Abstract

Study design

Retrospective cohort study.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of two periods of rehabilitation among people with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting

Shanghai Sunshine Rehabilitation Center (SSRC), China.

Methods

A total of 130 people with SCI who received two periods of rehabilitation participated in the study. Outcome measures included basic life skills (15 items) and their applications in family and social life (8 items). Six factors were identified from the 23 items by factor analysis: self-care and transfer skills; basic life skills application in social life; cognition and emotion; basic life skills application in family life; walking and climbing stairs; and wheelchair skills. Standardized scores ranging from 0 to 100 were used to show the rehabilitation outcome in a histogram.

Results

Median scores for self-care and transfer skills, wheelchair skills, cognition and emotion, and their applications in family and social life improved significantly (7−80%, p < 0.01) over the first rehabilitation period, while no improvement was observed in walking and climbing stairs. Five factors showed a significant sustained effect (p < 0.01) upon admission to the second rehabilitation period, except walking and climbing stairs. By enrolling in the second period of rehabilitation, participants acquired significant additional improvement (5−43%, p < 0.01) in rehabilitation outcomes, except in cognition and emotion, walking and climbing stairs.

Conclusions

Two periods of rehabilitation were efficacious at increasing the abilities of basic life skills and their applications in family and social life. The potential benefits of continuous rehabilitation merit further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although China has become the world’s second-largest economy since 2010, the allocation of resources to provide comprehensive rehabilitation to people with spinal cord injury (SCI) is still in its initial stages [1]. People with SCI in China can receive some hospital-based rehabilitation services after injury onset that focus on the improvement of self-care functions, complication prevention education, muscle strength exercises, and range-of-motion training, but there is an extreme lack of rehab training and follow-up with the aim of family and community integration [2]. In 2009, the China Association of Persons with Physical Disability, a government-funded organization, initiated community coop centers called “halfway houses”, a community-based rehabilitation (CBR) pilot project for people with SCI, in Shanghai and three other provinces [3]. Due to the lack of professional rehabilitation personnel in these houses, people with SCI have derived limited benefit from them; they urgently need rehabilitation care from professional caregivers at specialized, institution-based rehabilitation (SIBR) facilities [4]. To provide better professional inpatient rehabilitation training services in Shanghai, one of the first inpatient training facilities was started at the Shanghai Sunshine Rehabilitation Center (SSRC), a public center owned by the city of Shanghai. It provided a fixed, 45-day inpatient training program for people with SCI, and all costs were paid by the Shanghai Disabled Persons’ Federation (SDPF), a semi-government body. After the initial period of rehabilitation at the SSRC, people with SCI could apply for the second period of rehabilitation and be scheduled for training services sequentially according to their place in the application queue.

Although extensive studies on SCI rehabilitation have been performed in developed countries [4,5,6,7,8,9] and in China [10,11,12,13,14,15], no evidence is available on the effects of two periods of rehabilitation. To address this knowledge gap, this study adopted a retrospective cohort study design and aimed to evaluate the effects of two periods of rehabilitation for people with SCI in Shanghai. Its objectives were as follows: (1) to determine functional improvement over the initial period of rehabilitation, (2) to determine whether the effects of initial rehabilitation could be sustained over an average time of 1.5 years, and (3) to analyze whether additional improvement in function could be achieved through a second admission for an additional period of rehabilitation. These results can help inform rehabilitation policy in China, especially the rationale for potentially continuous rehabilitation.

Methods

Participants

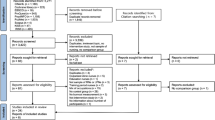

We included 130 people with SCI who received two periods of rehabilitation in the SSRC from 2013 to 2017. The enrollment process is described as follows.

First, people with SCI from the surrounding communities used documents certifying their disability to apply to the SDPF at the street (town) level for training openings; after examination and verification by the SDPF, the SSRC was responsible for providing inpatient rehab-training services to those who met the requirements set by the Federation, with admission in the order of their place in the application queue. To be eligible for the training, the participants needed to meet the following criteria: resident of Shanghai, certified with a physical disability, and without cognitive impairment or mental disability. In its actual operation, due to safety considerations and limited resources, the SSRC-training center had no ability to provide services for individuals with tetraplegia whose injury level was higher than C5. The SSRC was reimbursed from the SDPF according to a contract signed with the Federation. After their first 45-day rehabilitation, people with SCI who were younger than age 70 could apply for readmission, if they wished, and be enrolled in the second period of rehabilitation within 2 years. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the School of Public Health at Fudan University in Shanghai, China.

Intervention program

In compliance with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health’s “bio-psycho-social model” of disability, the integrated rehabilitation training program mainly included rehabilitation education and training in physical, psychological, and social functions [16, 17]. The feasibility and effectiveness of the program has been continually validated and perfected since 2009.

Rehabilitation education covers an introduction to SCI rehabilitation, prevention of complications (e.g., pressure sores), management of excretory functions, adaptation and use of assistive devices, psychological adjustment, and use of community resources or smart phones. Function reconstruction training includes physical therapy and occupational therapy (OT), which deals with activities of daily life (hand function, self-care, transfer, housework, and wheelchair skills training), vocation, and entertainment. Rehabilitation nursing includes training in excretory functions as well as skin care and body position management.

Rehabilitation doctors and nurses, psychological therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and social workers who had received a relevant bachelor’s degree or above and who had more than 5 years of SCI rehabilitation-related work experience were organized into the work team. They cooperated to provide rehabilitation training services and evaluate the functional outcomes of people with SCI. Upon admission and before discharge, people with SCI received an evaluation of their basic life skills (self-care, transfer, motor skills, cognition, and emotional abilities) and the applications of those skills in family and social life.

Because of limited space in the SSRC training center, no more than 20 people with SCI were enrolled in each fixed, 45-day rehabilitation program. The first and second periods of rehabilitation were individualized according to the level of lesion, personal needs, and baseline evaluation. When the participants were admitted to the program, the providers conferred with them individually to set up their expected functional improvement goals on specific factors after training. For example, an individual with thoracic cord injury might learn the skills of balance, lower limb dressing, and wheelchair skills. However, an individual with cervical cord injury might need hand function training. For the people with SCI who had grasped basic life skills, the training program focused on the applications of these capabilities in family and social life. Each participant, whether in the first or the second period of rehabilitation, received a personalized schedule, which normally included a 2-hour rehabilitation session in the morning and a 3-hour rehabilitation session in the afternoon on weekdays. On weekends, they often went on outings and other coop activities organized by peer mentors [18]. Each participant received a total of 90 training and practice sessions, with each session lasting for 1–2 h. Training methods included group discussion, demonstration, role-playing, and practice at different locations within or outside of the SSRC, such as the supermarket, cinema, restaurant, and subway station, to improve self-confidence and social adaptability.

Data and instruments

This study analyzed data extracted from the training records at the SSRC. The data included the individual’s sex, birth date, educational background, marital status, year of injury, cause of injury, level of lesion, and results of the evaluations of their basic life skills and the applications of those skills in family and social life. Marital status was classified as unmarried, married, divorced, or widowed. Levels of lesion were categorized into cervical, thoracic, and lumbosacral. The causes of injury were classified as traumatic and nontraumatic. Educational background was classified as illiteracy, elementary school, junior high school, senior high school, junior college, or regular college. Age was grouped as follows in the analysis: 18–30, 31–45, 46–60, and 61+.

The effect of training was evaluated in two parts (evaluation tables and criteria are attached in the Appendix): basic life skills and their applications in family and social life; the instruments had been used in our previous study in 2018 [15]. To ensure the validity of the outcome measures, a literature review, repeated discussions in the research group, relevant expert consultation, and repeated practice trials were conducted. Outcome measures of basic life skills included 15 items (self-care: eating, grooming, bathing, upper limb dressing, lower limb dressing, toileting; transfer: bed/chair/wheelchair transfer, toilet transfer, bath transfer; locomotion: walking, stairs, wheelchair; cognition and emotion: interpersonal communication, problem-solving, and emotion-handling) according to the training program, which made reference to the Functional Independence Measurement (FIM) scale [19, 20]. The grading criteria were the same as for the FIM (7: the best, which means complete independence; 1: the worst, which means total assistance) [21]. This measure showed excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.89 on admission and 0.87 at discharge). The evaluation framework for basic life skills applications in family and social life was validated in early studies [22, 23]. The evaluation of basic life skills application in family life included three secondary items (personal hygiene, housework, and entertainment), and the evaluation of basic life skills application in social life consisted of five secondary items (wheelchair use, transportation use, arrival at destination, completion of task, and communication skills); they were all rated by a six-point scale (0: the worst; 5: the best). The internal consistency reliability of this scale was also good (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83 on admission and 0.83 at discharge). One OT therapist was responsible for the baseline function evaluation on admission, and another OT therapist was responsible for the evaluation at discharge; both had received professional training in assessment.

Based on the admission scores of these participants on the 23-item instrument that assessed basic life skills and their applications in family and social life, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.83, and the value for the Bartlett test for sphericity (chi-square = 1844.3; df = 253; p < 0.01) indicated that the data supported factor analysis. The screen plot showed the existence of six factors that had Eigen values > 1.0, and the cumulative sum of squared loadings was 80.3%. After varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization, six factors were identified (rotated component matrix of factor analysis is attached in Appendix Table 1): self-care and transfer skills; basic life skills application in social life; cognition and emotional abilities; application of basic life skills in family life; walking and stair climbing skills; and wheelchair skills.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics included sex, age at injury, age on admission, educational background, cause of injury, marital status, level of lesion, and year of injury. All numerical variables were presented with means and standard deviations (SDs) if the p-value of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (normality test) was >0.05; otherwise, medians with ranges or interquartile ranges (IQRs) were provided. Exploratory factor analysis was used to identify the underlying factors from the 23 items of basic life skills and their applications in family and social life. The subtotal scores of each factor were used in the analysis, which were the sums of the original scores of corresponding items for every factor.

If A is defined as the score at admission and D is defined as the score at discharge, C is defined as the relative score change between the two scores: C (%) = (D − A)/A × 100. Then subscripts 1 and 2 represent the participants’ first and second periods of rehabilitation, respectively:

The sustained effect (1): ΔA1A2 (%) = [(A2 − A1)/A1] × 100, i.e., the baseline difference between the first admission and the second admission;

The sustained effect (2): ΔD1A2 (%) = [(A2 − D1)/D1] × 100, i.e., the proportional changes of the factors’ scores between the first discharge and the second admission.

The total effect of two rehabilitation periods: ΔA1D2 (%) = [(D2 − A1)/A1] × 100.

The Wilcoxon test of paired samples was used to evaluate the significance of differences in the scores for each factor. Because the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) applicable to our instrument has not been established in the field [24], the score increase with statistical significance was regarded as the MCID in our study [24, 25]. Histograms with standardized scores were used to show the rehabilitation outcome of the two periods of rehabilitation, with the lower edge and the upper edge of the columns representing the standardized admission scores and standardized discharge scores, respectively.

The transformation formula of a standardized score with a range of 0–100 was as follows: S = [(R − min)/(max − min)] × 100.

The variables represent the following: S: standardized score; R: the sums of the original scores of corresponding items for every factor; and min and max: the minimum and maximum value of the total possible sums of the original scores of the corresponding items for every factor.

All statistical tests were two-sided with a significant p-value ≤ 0.05. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows (SPSS for Windows 13.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

Results

Social demographics and general injury characteristics of people with SCI

Among the 130 participants who received two rehabilitation periods, the ratio of men to women was 2.1:1 (Table 1). The mean (SD) age at admission was 47.5 (12.4) years. The mean (SD) age at injury was 32.7 (15.8) years. The median time (IQR) from injury to the beginning of the rehabilitation training at the SSRC was 10.5 (2–26) years. The median (mean) time gap was 1 (1.5) year, ranging from 1 to 4 years. The main age groups were 46–60 years (46%, Table 1) and 18–30 years (21%); among them, 63% suffered injury before 2009, and trauma was the principal cause of SCI (81%).

Effectiveness analysis of the first rehabilitation period

As shown in Table 2, a significant increase in the median scores of five factors, except for walking and climbing stairs, could be observed between admission and discharge (p < 0.01) over the first rehabilitation period. The median scores of the “wheelchair skills” factor showed the largest improvement (80%, Table 2), followed by application in family life (56%), self-care and transfer skills (17%), cognition and emotion (13%), and application in social life (7%). The improvements in these five factors (except walking and climbing stairs) reached clinical significance. However, it should be observed that the standardized score for “wheelchair skills” on admission was the second-lowest (36.4, Fig.1; the lowest was 0.0 [walking and climbing stairs]), while the baseline standardized score for “application in social life” reached as high as 75.0. On discharge, the standardized scores of the six factors from high to low were as follows: self-care and transfer skills (91.5), cognition and emotion (83.3), application in social life (80.0), wheelchair skills (72.7), application in family life (70.0), and walking and climbing stairs (0.0).

Sustained effect analysis of the first rehabilitation period

The median scores for cognition and emotion and for application in social life remained unchanged between the first discharge and the second admission (Table 2); that of self-care and transfer skills increased by one point with no statistical significance (p = 1.00), i.e., these three factors showed a sustained effect after an average time period of 1.5 years following discharge from the first rehabilitation period. But the scores for wheelchair use and basic life skills application in family life distinctly decreased between the first discharge and the second admission (−22% and −14%, respectively, p < 0.01). However, a comparison of the two admission scores of these two factors indicated that they still significantly increased by 40% and 33% (Table 2, p < 0.01), respectively. In conclusion, we observed sustained effect on five factors, apart from walking and climbing stairs, of the first rehabilitation period after an average time period of 1.5 years.

Effectiveness analysis of the second rehabilitation period

A significant increase (Table 2) in the scores for four factors between admission and discharge could also be observed over the second rehabilitation period (p < 0.01): wheelchair skills (43%), application in family life (33%), application in social life (6%) and self-care and transfer skills (5%), while no changes were observed in the scores for cognition and emotion and for walking and climbing stairs. In other words, a significant clinical effect could still be observed in basic life skills and their applications in family and social life in the second rehabilitation period. From high to low, the standardized scores for the six factors at the time of discharge from the second rehabilitation period were as follows (Fig. 1): self-care and transfer skills (98.3), application in social life (85.0), cognition and emotion (83.3), wheelchair use (81.8), application in family life (80.0), and walking and climbing stairs (0.0). The median scores of these six factors increased by 100% for wheelchair skills (Table 2) from first admission to second discharge, 78% for application in family life, 24% for self-care and transfer skills 13% for application in social life, 13% for cognition and emotion, and 0 for walking and climbing stairs.

Discussion

This study provides initial evidence describing the outcomes of two periods of rehabilitation at the SSRC. The effectiveness of rehabilitation training was satisfactory, with a significantly sustained effect by the time of admission for the second rehabilitation period. Though the scores for the application of acquired skills in the setting of family life and wheelchair abilities declined markedly after the first discharge, they still showed significant improvement from the first admission to the second admission. Since only a small percentage of people with SCI can receive SIBR services in China at this time, more efforts and resources should be put into the SIBR area to provide more training opportunities for those who have not taken part in training [26]. For instance, hospitals should refer newly injured people with SCI to the SSRC to receive timely rehabilitation training after discharge, and community residents with SCI who have not participated in rehabilitation training could also be recommended to the SSRC in due course. Furthermore, it is important to educate both people with SCI and their caregivers about the health benefits of SIBR by providing health education on this issue to medical professionals and the general public.

Based on the discharge summaries, all people who received two periods of rehabilitation achieved their expected functional outcomes except for walking and climbing stairs upon discharge. It is important to note that the functional outcome expectations of people with SCI varied and were often higher upon second admission than upon first admission. Functional improvements with clinical significance in basic life skills and their applications in family and social life were achieved by the second period of rehabilitation. To be more concrete, based upon our observations, people with thoracic and lumbosacral cord injury could acquire the abilities to live independently, and people with cervical SCI could further decrease their level of dependency if both groups were given a second period of rehabilitation. Although this study has provided preliminary evidence regarding the medical, psychological, and social value of additional rehabilitation periods, owing to the limited scale of existing services, the CBRs (e.g., “halfway houses”) are still the cornerstone resource for people with SCI in mainland China [3, 27, 28].

Our results indicate that rehabilitation training could provide better outcomes for basic life skills application in family life than for application in social life, since there was more room for improvement in the former than in the latter. It remains a challenge in rehabilitation practice to improve skill applications in family and social life as well as providing support for cognition and emotional abilities given the limited resources in the SSRC. A feasible alternative could be to foster CBR and provide systematic and sustainable social support to people with SCI [29] from the point of injury onset until integration into their families and society based on a management information system. Another issue is ease of access for people with SCI. Considering that most people with SCI are wheelchair-dependent, the room for improvement in walking and climbing stairs is very limited, as our results suggested. Though there was a marked increase in wheelchair skills over the first and second periods of rehabilitation, the sustained effect was not satisfactory between the first discharge and the second admission, which could be related to reduced wheelchair use in that time interval. The barrier-free environment in Shanghai is still limited, which creates an obstructive environment for using wheelchairs in homes and communities [30, 31]. While patients could significantly improve their wheelchair skills at the SSRC, the lack of sufficient accessible facilities in their communities would lead to a decline in their wheelchair abilities. This implies that a barrier-free environment and housing is an essential factor in helping people with SCI reintegrate into their families and society [32].

This study has a few limitations to acknowledge. First, the sample size is limited, given the low incidence of SCI. Second, we did not collect information on training processes, training cost, complications, follow-up outcomes such as whether patients could return to work, or other additional effects because of limited resources for data collection. Third, no control group was included in our study. Fourth, the scales have ceiling effects, which means that we cannot compare the outcome differences of the two periods of rehabilitation based on their score changes. Finally, interrater reliability was not examined in this study.

In summary, this study evaluated the rehabilitation outcomes of 130 people with SCI who participated in two periods of rehabilitation at the SSRC. Our results revealed significant outcome improvement with the first rehabilitation period. The outcome showed a sustained effect for a mean of 1.5 years after discharge from the first rehabilitation period, and those with SCI acquired additional significant improvement in basic life skills and their applications in family and social life during the second rehabilitation period. Therefore, our study has provided preliminary evidence supporting SIBR for people with SCI in Shanghai as well as evidence for the value of replicating the SSRC model in other developed regions in China. In fact, more SIBR facilities, such as the SSRC, are needed to provide effective training to more people with SCI in Shanghai.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the SSRC.

References

Yang ML, Li JJ, Li Q, Qiu ZY, Chen C, Gao F. Clinic and rehabilitation pathway recommendation for spine and spinal cord injury. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. 2012;18:791–6. (in Chinese)

Li J, Liu G, Zheng Y, Hao C, Zhang Y, Wei B, et al. The epidemiological survey of acute traumatic spinal cord injury (ATSCI) of 2002 in Beijing municipality. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:777–82.

Chang FS, Zhang Q, Sun M, Yu HJ, Hu LJ, Wu JH, et al. Epidemiological study of spinal cord injury individuals from halfway houses in Shanghai, China. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;41:450–8.

Cheng CL, Plashkes T, Shen T, Fallah N, Humphreys S, O’Connell C, et al. Does specialized inpatient rehabilitation affect whether or not people with traumatic spinal cord injury return home? J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:2867–76.

Turner-Stokes L, Vanderstay R, Stevermuer T, Simmonds F, Khan F, Eagar K. Comparison of rehabilitation outcomes for long term neurological conditions: a cohort analysis of the Australian rehabilitation outcomes centre dataset for adults of working age. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e132275.

Guihan M, Bombardier CH, Ehde DM, Rapacki LM, Rogers TJ, Bates-Jensen B, et al. Comparing multicomponent interventions to improve skin care behaviors and prevent recurrence in veterans hospitalized for severe pressure ulcers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:1246–53.

Hachem LD, Ahuja CS, Fehlings MG. Assessment and management of acute spinal cord injury: From point of injury to rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40:665–75.

Tse CM, Chisholm AE, Lam T, Eng JJ. A systematic review of the effectiveness of task-specific rehabilitation interventions for improving independent sitting and standing function in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41:254–66.

Truchon C, Fallah N, Santos A, Vachon J, Noonan VK, Cheng CL. Impact of therapy on recovery during rehabilitation in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:2901–9.

Bi JX, Yu ZH, Wang SL. Impact of rehabilitation training on spinal cord injury patients. J Qilu Nurs. 2011;20:38. (in Chinese)

Shen HL, Wu GQ, Pan YQ. Outcomes of rehabilitation training of 106 spinal cord injury patients. Fujian Med J. 2017;39:162–3. (in Chinese)

Chan SC, Chan AP. Rehabilitation outcomes following traumatic spinal cord injury in a tertiary spinal cord injury centre: a comparison with an international standard. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:489–98.

Wang YY, Yang M. Effects of family rehabilitation training and nursing on the prognosis of patients with spinal cord injury and paraplegia. Hainan Med J. 2014;25:1862–4. (in Chinese)

Ru ZH, Wu H. Effects of community rehabilitation guidance on the complications and quality of life of patients with spinal cord injury. Chin Rural Health Serv Adm. 2013;33:1231–3. (in Chinese)

Xie HX, Chang FS, Shen C, Shen XY, Zhang J, Lin PP, et al. Factors influencing the outcomes of specialized institution-based rehabilitation in spinal cord injury. Chin J Spine Spinal Cord. 2018;28:529–34. (in Chinese)

Hou CL, Fan ZP, Wang SB. Guideline for spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers; 2006. (in Chinese)

Xu FJ. Guide book for rehabilitation of halfway house of spinal cord injury patients. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers; 2010. (in Chinese)

Gassaway J, Jones ML, Sweatman WM, Hong M, Anziano P, DeVault K. Effects of peer mentoring on self-efficacy and hospital readmission after inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2017;98:1526–34.

Dodds TA, Martin DP, Stolov WC, Deyo RA. A validation of the functional independence measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:531–6.

Donaghy S, Wass PJ. Interrater reliability of the functional assessment measure in a brain injury rehabilitation program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1231–6.

Maynard FM, Bracken MB, Creasey G, Ditunno JF, Donovan WH, Ducker TB, et al. International standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:266–74.

Shen JH. Training mobility orientation among the blind population. Beijing: HuaXia publishing house; 2008. (in Chinese)

Xu HM. Study on effect evaluation criteria of mobility orientation training among the blind population. J Mod Spec Educ. 2010;Z1:38–40. (in Chinese)

Wu X, Liu J, Tanadini LG, Lammertse DP, Blight AR, Kramer JL, et al. Challenges for defining minimal clinically important difference (MCID) after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:84–91.

Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW, Lammertse D, Kalichman M, Rask C, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP Panel: clinical trial inclusion exclusion criteria and ethics. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:222–31.

Herzer KR, Chen Y, Heinemann AW, Gonzalez-Fernandez M. Association between time to rehabilitation and outcomes after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:1620–7.

Lin HM. Influence of supportive psychological intervention on community patients with spinal cord injury. Chin Gen Pract Nursing. 2013;11:485–7. (in Chinese)

Zhang L. Effectiveness evaluation of home-based rehabilitation nursing of 24 spinal cord injury patients. Mod Rehabil. 2000;4:1409–10. (in Chinese)

Forchheimer M, Tate DG. Enhancing community re-integration following spinal cord injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19:103–13.

Pan HS, Zou W, Zhao T, Zhang YF. Rethinking barrier-free environment construction in shanghai metro transport. Shanghai Urban Plan Rev. 2013;2:70–6. (in Chinese)

Zhang DW. The status quo, problems and countermeasures in the construction of barrier-free environment in china. Hebei Acad J. 2014;34:122–5. (in Chinese)

Nas K, Yazmalar L, Şah V, Aydin A, Öneş K. Rehabilitation of spinal cord injuries. World J Orthop. 2015;6:8–16.

Acknowledgements

We express thanks to the SSRC staff for their help in collecting data and to all people with SCI who participated in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [71673052], the China Scholarship Council [201506105030], and the Shanghai Pujiang Program of the Shanghai Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau [17PJC003]. It was also a project of key disciplines construction from the Shanghai Disabled Persons’ Federation [No. 2015–139], was supported by the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth 5-year Plan Period [2014BAI08B01] and the 111 Project [Grant Number B16031], and was a major project of the National Social Science of China [No.17ZDA078].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FSC was responsible for conducting the data analysis and preparing the article. JL was responsible for data interpretation. QZ was responsible for the study design, method implementation, and paper revision. HXX was responsible for data collection and contributed to the interpretation of results. YHY, CS, XYS, and ARW contributed to data collection. HFW, GC, and XHL contributed to data interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, F., Zhang, Q., Xie, H. et al. The effects of two periods of rehabilitation for people with spinal cord injury from Shanghai, China. Spinal Cord 58, 216–223 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0349-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0349-2

This article is cited by

-

Effects of a rehabilitation program for individuals with chronic spinal cord injury in Shanghai, China

BMC Health Services Research (2020)