Abstract

This report documents a unique multicystic neoplasm of the liver in an 8-month-old boy with a heterozygous germline pathogenic DICER1 variant. This neoplasm, initially considered most likely a mesenchymal hamartoma based on imaging, demonstrated the characteristic histologic pattern of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma residing in the subepithelial or cambium layer-like zone of the epithelial-lined cysts. Thus, although the differential diagnosis includes mesenchymal hamartoma, a young child with a multicystic mass lesion in the liver, lung, or kidney should both raise the possibility of a germline pathogenic DICER1 variant and also not be mistaken for one of the other hepatic neoplasms of childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a measure of the critical, essential role of the gene DICER1 (14q32.13), its protein product contains two functional enzymatic RNase domains, RNase IIIa and RNase IIIb. The RNase domains are responsible for the generation of virtually all microRNAs (miRNA); the latter are the effectors of a highly conserved gene silencing system with multifaceted roles in post-transcriptional gene regulation1,2. Perturbations in organogenesis are fully anticipated in the absence of DICER1 and in fact, DICER1 is essential in the self-renewal of embryonic stem cells3. Knockout of both alleles of DICER1 in early mouse embryos has been shown to be lethal. It was observed that the inactivation in mouse embryonic lung, using a DICER1 conditional allele, caused an arrest in branching morphogenesis resulting in the development of cysts4. The morphologic resemblance of these lung cysts to type I pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) helped catapult DICER1 to the top of the list of candidate genes within a 72 Mb window on chromosome 14 identified in a family linkage study of families with children who had developed PPB5. From that initial observation has evolved the spectrum of organ-based tumors now known to be associated with DICER1 variation6.

The various affected organs and specific anatomic sites in which DICER1-related tumors may develop have expanded beyond the lung to include the kidney, thyroid, female genital tract including the ovary, uterine cervix, and fallopian tubes, eye, and central nervous system. Some of these sites, like the lungs, kidney, thyroid, and uterine cervix, are linked in part by the developmental process of branching morphogenesis7. As noted earlier, it was the interruption of DICER1 in the lung which led to the hypothesis that a mutation in this gene may be the underlying foundation of this apparent familial condition with its archetypical neoplasm, the PPB. Cysts resembling those of type I PPB are also features of pediatric cystic nephroma, Sertoli-Leydig tumor of the ovary, and PPB-like peritoneal sarcoma, all of which present in the setting of DICER1 germline and somatic “hotspot” variants or biallelic somatic hotspot mutations6. The morphologic motif in association with these cysts in the lung and elsewhere is a compact, subepithelial population of primitive small cells with or without rhabdomyoblastic differentiation producing a so-called cambium layer, the characteristic microscopic feature of botryoid embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma8.

The present study is a report of an 8-month-old boy with a cystic hepatic mass and a polyp in the small intestine. Subsequent genetic evaluation revealed a heterozygous germline pathogenic DICER1 variant in this infant. This hepatic neoplasm with its distinctive pathologic features establishes the liver as another site for DICER1-associated malignancies.

Materials and methods

Study subject and clinical data ascertainment

Children and adults with known or suspected PPB or DICER1-related conditions were enrolled in the International PPB/DICER1 Registry (www.PPBregistry.org). All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children’s Minnesota, Children’s National Medical Center, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta/Emory University, and Washington University in St. Louis. All pathology was centrally reviewed per standard Registry procedures (LPD). Medical records including operative, pathology, and imaging reports and treatment data were reviewed. Follow-up data was requested at least annually.

Molecular analyses

For germline testing, genomic DNA was extracted from blood; enriched targets were sequenced on an Illumina platform. DICER1 gene sequencing was performed on tumor tissue using a next-generation sequencing assay designed to detect base substitutions and small insertions/deletions in both coding and intron/exon flanking regions.

Results

Review of the International PPB/DICER1 Registry files revealed a unique case of hepatic malignancy associated with DICER1 in an 8-month-old boy who presented with abdominal distention. A hepatic mass was noted by ultrasound. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a large cystic mass with a thick peripheral capsule and multiple internal septations arising from the right hepatic lobe, measuring 10 × 12 × 12 cm. The tumor caused mass effect on the undersurface of the liver and displaced the gallbladder posteriorly (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the MRI also revealed an elongated, thickened loop of small bowel with a target appearance in the left lower quadrant consistent with small bowel intussusception. Physical examination revealed an abdominal mass and macrocephaly; no clinical signs or symptoms of intussusception were noted. Laboratory studies were remarkable for an elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) at 130 U/L (normal 23–83 U/L), elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at 172 U/L (normal 6–50 U/L), and a normal alpha fetoprotein (AFP) at 6 ng/ml (normal 1–28 ng/ml).

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy with excision of the liver mass and resection of the small bowel intussusception; a polyp was detected as a lead point. An institutional diagnosis of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the biliary tree was determined, Stage 1, Group 2, based on a microscopic positive surgical margin, negative post-operative positron emission tomography (PET) scan, and negative bilateral bone marrow biopsies and aspirates. The polyp was confirmed as a juvenile polyp. The patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide as per ARST0331, regimen A, and local control with proton radiation.

During staging evaluation, he was found to have bilateral lung cysts on chest computed tomography (CT) imaging, the largest of which was in the left lower lobe measuring 2 × 2 × 3 cm. He underwent resection of two left lung cysts, and central pathology review confirmed Type Ir PPB for both lesions. He remains well approximately one month after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation.

Pathologic findings

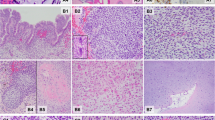

The hepatic tumor measured 10.7 × 9.1 × 1.6 cm and weighed 198 gm. Its cut surface had a multicystic appearance and the cysts had smooth surfaces. A clear serous fluid exuded from the exposed surface. The external surface was smooth and without any excrescences (Fig. 2A).

A A well-circumscribed predominantly cystic mass showing the septal structures between variably-sized cysts and solid foci. B A septum showing a subepithelial population of small primitive cells forming a cambium layer. (Inset): Intense desmin immunostaining in the cambium layer. C A more densely cellular cambium layer with extension of tumor cells into the septal stroma. D Two adjacent cysts, one with a cambium layer of small primitive cells and the other with a circumferential zone of fibrous stroma.

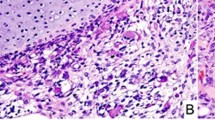

Microscopically, the cysts were lined by a cuboidal to columnar biliary type epithelium and many, but not all epithelial-lined cysts were accompanied by a concentric mantle of compact, undifferentiated, small, round to spindle-shaped cells with a cambium layer-like appearance (Fig. 2B, C). The tumor cells extended into the surrounding surface. Though rhabdomyoblastic differentiation was not readily apparent, the desmin immunostaining was intensely positive, but in the absence of myogenin and myoD1 reactivity (Fig. 2B, inset). Other cysts were accompanied by a fibrous stroma in the absence of a cambium layer (Fig. 2D). Additional features included an overall fibrous stroma and focal areas of small bile ducts arranged in groups representing atrophic liver remnants. A myxomatous mesenchymal stroma with or without pools of extracellular fluid, small individual or networks of abnormally formed bile ducts resembling a bile duct malformation, islands of hepatocytes, and extramedullary hematopoiesis were not present as the characteristic features of mesenchymal hamartoma9. No additional cystic lesions were identified in a background of the uninvolved liver, but rather non-specific changes adjacent to the mass.

The polyp of the small intestine was composed of crypts with progressive dilatation from the periphery to the center and bands of muscularis within the lamina propria. There was an absence of an arborizing architecture of smooth muscle nor a branching proliferation of the epithelium.

Molecular studies

Blood testing showed a heterozygous small deletion in DICER1 NM_177438.3:c.4407_4410delTTCT; p.Ser1470Leufs*19 leading to premature truncation of the protein. The remainder of a 17-gene panel was negative for pathogenic alterations.

Molecular testing performed on the tumor sample showed a DICER1 hotspot in the RNase IIIb domain (c.5438A > G; p.Glu1813Gly missense) in addition to the known germline deletion.

Discussion

This report documents our experience with a unique cystic neoplasm of the liver associated with a heterozygous germline pathogenic DICER1 variant. After further pathologic review, the tumor was more accurately described as intraparenchymal, and not associated with the common bile or hepatic duct system; a botryoid presentation of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma within the hepatobiliary tract with obstructive signs is an uncommon but documented presentation which was not present in this case10. In terms of gross pathologic findings, its multicystic features have overlapping features with the mesenchymal hamartoma, but the microscopic attributes are distinctly different. This corresponds to other DICER1-associated neoplasms with early morphologic stages characterized by the development of multiple cysts and in varied anatomic locations including the lung, kidney, or peritoneal cavity. The archetype of these cystic neoplasms is the pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) whose earliest recognizable lesion is a circumscribed, multicystic structure composed of dilated profiles of peripheral airspaces and septa with or without hypercellular features; the latter are composed of neoplastic, small primitive tumor cells with or without rhabdomyoblastic differentiation in which case an interpretation of type I PPB is made. The proliferative small cell component may be localized in the type I PPB or completely absent as in the type IR PPB. Tumor progression in type I PPB is evidenced by the development of a solid mass and the emergence of a complex, multi-patterned sarcoma with a collage of rhabdomyosarcoma, spindle cell sarcoma, small nests of primitive blastema, chondrosarcoma, and anaplastic cells. Further, a similar tumor progression is recognized in the central nervous system, in the kidney, and in the female genital tract of patients with pathogenic germline DICER1 variants.

This serves to document the liver as another primary site for a DICER1-associated neoplasm whose cystic features have a broad similarity to type I PPB: a cambium layer of rhabdomyoblastic cells beneath an epithelial lining with microscopic invasion of the adjacent stroma and without the formation of a discrete mass8. Our case demonstrates this important feature which was not in evidence in the two hepatic cystic lesions in 26-month-old and 39-month-old males with DICER1 syndrome, previously reported by Apellaniz-Ruiz et al as mesenchymal hamartomas11. There is no dispute that these respective lesions, 19 cm and 6.6 cm cysts, have gross features resembling mesenchymal hamartomas, and even some histologic findings which could be interpreted as the latter as discussed in a follow-up correspondence by Vargas and Perez-Atayde12. Many of the epithelial-lined cysts in our case were lined by biliary type epithelium and surrounded by mantles of rhabdomyoblastic cells with focal invasion into the surrounding stroma by these neoplastic cells. The cystic structures in the two previously-reported DICER1 “mesenchymal hamartomas” were lined by a relatively inconspicuous epithelial lining and a fibrous or fibromyxoid stroma whose features are reminiscent of PPB type IR8. As Vargas and Perez-Atayde state, the mesenchymal hamartoma has distinctive pathologic features unlike those reported by Apellaniz-Ruiz et al as well as a molecular rearrangement in 19q13.4211,12,13.

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver (UESL) is a predominantly solid, often myxomatous and hemorrhagic mass which may have cystic foci. However, these are not lined by an epithelium, but rather represent cystic degeneration without any features of a cambium layer of small primitive cells and/or rhabdomyoblasts as in our case. UESL has a range of histologic patterns from primitive stellate cells, epithelioid or rounded cells including rhabdoid cells to multinucleated giant cells with hyaline globules14. Microscopic cystic structures with features of bile ducts are often found at the periphery of the pseudocapsular interface with the compressed liver; these small cysts are not accompanied by a cambium layer of tumor cells. Though individual tumor cells may demonstrate desmin reactivity, the cells do not express myoD1 or myogenin. Progression of a DICER1-associated cystic hepatic neoplasm has been reported in a 16-year-old female who presented with a cystic lesion in the liver whose cystic foci resembled our case, but in addition had a spindle cell sarcomatous pattern and myxoid stroma as seen in type II/III PPB as well as other DICER1 sarcomas15. The tumor recurred three years later as a spindle cell sarcoma. This patient had a DICER1 germline pathogenic variant and the tumor had a second somatic DICER1 variant. She also had other pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations of DICER1 variation.

We would argue that it is not necessary to postulate some molecular interaction between DICER1 and chromosome 19q13.42 though there is a miRNA cluster (C19MC) in the latter11. The pathologic findings of these cystic hepatic neoplasms, including the previously reported “mesenchymal hamartomas”, are concordant with other examples of DICER1-associated tumors, prompting proposal of the novel designation “DICER1-associated cystic hepatic neoplasm with PPB-like features” in our case as well as the two earlier cases11. The fibrous stroma around the cysts in the latter two cases is very similar to the pattern in PPB type IR, cystic nephroma, and DICER1 peritoneal sarcoma; several of the cysts in our case had such features without a cambium layer of rhabdomyoblasts. Like their Case 2, our patient had a juvenile polyp. Juvenile polyps have been described in multiple individuals with germline DICER1 pathogenic variation including those with mosaic RNase IIIb pathogenic variation16. Further, our patient had macrocephaly, a known overgrowth in the setting of pathogenic germline DICER1 variants17.

We expect complex, multi-patterned primitive sarcomas of the liver will be reported in the future with features resembling those of PPB type II or III, anaplastic sarcoma of the kidney, or one of the other similar-appearing DICER1-associated sarcomas. When one of these neoplasms is encountered or suspected, appropriate genetic studies should be recommended18.

References

Bernstein, E. et al. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat. Genet. 35, 215–217 (2003).

Thunders, M. & Delahunt, B. Gene of the month: DICER1: ruler and controller. J. Clin. Pathol. 74, 69–72 (2021).

Teijeiro, V. et al. DICER1 is essential for self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 11, 616–625 (2018).

Harris, K. S., Zhang, Z., McManus, M. T., Harfe, B. D. & Sun, X. Dicer function is essential for lung epithelium morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2208–2213 (2006).

Hill, D. A. et al. DICER1 mutations in familial pleuropulmonary blastoma. Science 325, 965 (2009).

Schultz, K. A. P. et al. DICER1 Tumor predisposition. In: M. P. Adam et al. (eds). GeneReviews((R)) (Seattle (WA), 1993).

Goodwin, K. & Nelson, C. M. Branching morphogenesis. Development 147, 1–6 (2020).

Hill, D. A. et al. Type I pleuropulmonary blastoma: pathology and biology study of 51 cases from the international pleuropulmonary blastoma registry. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 32, 282–295 (2008).

Martins-Filho, S. N. & Putra, J. Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma and undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: a pathologic review. Hepat. Oncol. 7, HEP19 (2020).

Nicol, K. et al. Distinguishing undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver from biliary tract rhabdomyosarcoma: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 10, 89–97 (2007).

Apellaniz-Ruiz, M. et al. Mesenchymal Hamartoma of the Liver and DICER1 Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1834–1842 (2019).

Vargas, S. O. & Perez-Atayde, A. R. Mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver and DICER1 syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 586–587 (2019).

Mathews, J., Duncavage, E. J. & Pfeifer, J. D. Characterization of translocations in mesenchymal hamartoma and undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 95, 319–324 (2013).

Martins-Filho, S. N. & Putra, J. Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma and undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: a pathologic review. Hepat. Oncol. 7, HEP19–HEP19 (2020).

See, S. C., Wadhwani, N. R., Yap, K. L. & Arva, N. C. Primary biphasic hepatic sarcoma in DICER1 syndrome. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1177/10935266211008443 (2021).

Brenneman, M. et al. Temporal order of RNase IIIb and loss-of-function mutations during development determines phenotype in pleuropulmonary blastoma / DICER1 syndrome: a unique variant of the two-hit tumor suppression model. F1000Res 4, 214 (2015).

Khan, N. E. et al. Macrocephaly associated with the DICER1 syndrome. Genet. Med. 19, 244–248 (2017).

Schultz, K. A. P. et al. DICER1 and associated conditions: identification of at-risk individuals and recommended surveillance strategies. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 2251–2261 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the many treating physicians, genetic counselors, patients, and families who collaboratively support the International PPB/DICER1 Registry and the Pine Tree Apple Classic Fund whose volunteers, tennis players, and donors have provided more than 30 years of continuous support for PPB and DICER1 research. Specifically, this work was supported by the Pine Tree Apple Tennis Classic Fund. The International PPB/DICER1 Registry is also supported by the Children’s Minnesota Foundation and Rein in Sarcoma. K.A.S., D.A.H. and P.M. also receive support from NIH/NCI 1R37CA244940.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors collated clinical and pathologic data and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. DAH is the owner of ResourcePath LLC, a company that does research and development of laboratory tests including for DICER1 cancers. That work is unrelated to the information presented in this article.

Ethics approval/Consent to participate

Human subjects approval was provided by the respective institutions’ review board. Informed consent was obtained for research participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mitchell, S.G., Schultz, K.A.P., Rytting, H. et al. DICER1-associated hepatic cystic neoplasm with pleuropulmonary blastoma-like features: a novel clinicopathologic diagnosis. Mod Pathol 35, 676–679 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00947-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00947-y