Abstract

Colostrum is a complex source of nutrients, immune factors, and bioactive substances consumed by newborn mammals. In previous work, we observed that protein synthesis in the skeletal muscle of newborn piglets is enhanced when they are fed colostrum rather than a nutrient-matched formula devoid of growth factors. To elucidate the mechanisms responsible for this response, we contrasted the fractional rates of sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar protein synthesis of newborn piglets that received only water with those fed for 24 h with colostrum, a nutrient-matched formula, or mature sow's milk. Compared with water, feeding resulted in a 2.5- to 3-fold increase in total skeletal muscle protein synthesis, and this increase was 28% greater in the colostrum-fed than either the formula- or mature milk-fed piglets. Feeding also stimulated muscle ribosome and total polyadenylated RNA accretion. Ribosomal translational efficiency, however, was similar across all fed groups. The greater stimulation of protein synthesis in colostrum-fed pigs was restricted entirely to the myofibrillar protein compartment and was associated with higher ribosome and myosin heavy chain mRNA abundance. Taken together, these data suggest that nonnutritive factors in colostrum enhance ribosomal accretion and muscle-specific gene transcription that, in turn, stimulate specifically the synthesis of myofibrillar proteins in the skeletal musculature of the newborn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Colostrum is a source of nutrients, immune factors, and bioactive substances for the newborn mammal. Although the benefits of the consumption of nutrients and immune factors are readily apparent, the functional significance to the offspring of the numerous hormones and growth factors present in colostrum is unclear. Studies that have compared the growth of newborns have demonstrated an enhanced anabolic response, especially of the visceral organs, associated with colostrum feeding (1–4). This response is often attributed to the presence of trophic factors, but this speculation remains to be proven. In addition, inadequate consideration has been given to the fact that the consumption of colostrum also entails the ingestion of a larger quantity of nutrients than that typically provided by mature milk or many formulas. Thus, to distinguish between the stimulatory effects of macronutrient intake and the trophic effects of other growth-promoting substances in colostrum, we compared the protein synthetic response of newborn piglets to feeding with colostrum, mature sow's milk, or a formula with a macronutrient composition similar to that of colostrum but devoid of potentially bioactive molecules (5, 6). We observed that protein synthesis rates in skeletal and cardiac muscle, brain, and jejunum were higher in colostrum-fed than formula-fed piglets; other organs did not show this enhanced response.

The high rate of protein synthesis associated with colostrum consumption could have resulted from an increase in the capacity for protein synthesis due to a stimulation of ribosomal accretion and/or an increase in the quantity of proteins synthesized per ribosome, i.e. an increase in ribosome translational efficiency. Improvements in translational efficiency usually occur when there is an enhancement in the initiation of translation due to increases in the availability of active initiation factors. An increase in the abundance of mRNA presented to the ribosome for translation could also lead to an apparent increase in translational efficiency, although this would indicate that mRNA availability rather than ribosomal abundance is a primary limitation to protein synthesis.

Our overall objective was to identify the mechanism whereby the ingestion of colostrum stimulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis rates in the neonate. Specifically, we wished to determine whether the response was due to an increase in translation efficiency and/or ribosomal abundance and whether the increase in protein synthesis was specific for individual muscle proteins. We found that the synthesis rate of only the myofibrillar proteins was stimulated by colostrum and, therefore, further examined whether this effect could be explained by changes in the abundance muscle-specific mRNA.

METHODS

Experimental design and animals.

The experimental procedures have been described previously (6). Briefly, three litters of conventional cross-bred pigs were removed from the sow immediately after birth and not allowed to suckle. Piglets were fitted with umbilical artery catheters under general isoflurane anesthesia. The piglets were randomly assigned to one of three dietary groups and fed for 24 h with mature sow's milk (n = 5), formula (n = 5), or sow colostrum (n = 5); a fourth group (n = 4) was studied at approximately 5 h of age, having received only water. Blood samples were collected for analysis of glucose, amino acids, insulin, and IGF-I concentrations before and during the feeding period. After 24 h, protein synthesis was measured in vivo, and the longissimus dorsi muscle was collected for determination of total myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic protein FSR, total protein and total RNA concentrations, polyA RNA, 18S rRNA, and MHC mRNA abundance. The animal protocol was conducted in accordance with the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee.

Feeding protocol.

The piglets were weighed at the start of the feeding protocol and then bottle-fed hourly one of the three feeds at a rate of 20 mL/kg body weight. The exact weight consumed was determined by weighing the bottle before and after the feed. The colostrum and mature milk were collected from conventional sows within 24 h of parturition and during the third week postpartum, respectively. A single batch of each feed was used throughout the experiment. The colostrum was analyzed for fat (7), lactose (YSI automatic analyzer, model 127, Yellow Springs, OH, U.S.A.), total protein (Kjeldahl method after trichloroacetic acid precipitation of protein and assuming a conversion factor of 6.38 for nitrogen to protein; Kjeltec Auto Analyzer 1030, Tecator, Hoganas, Sweden), and total energy content (adiabatic bomb calorimetry; Parr Instruments, Moline, IL, U.S.A.). The formula then was constructed from semipurified ingredients to match the macronutrient composition of the colostrum. The composition of the formula per liter was (in grams) 51.4 casein, 53.9 lactalbumin, 23.1 albumin, 35.0 lactose, 35.0 corn oil, 35.0 coconut oil, 5.0 vitamin mix (containing per gram of mix 900 IU retinyl acetate, 106 IU vitamin D2, 22 mg dl-α-tocopherol acetate, 45 mg ascorbic acid, 5 mg inositol, 75 mg choline chloride, 2.25 mg menadione, 5 mg p-aminobenzoic acid, 4.25 mg niacin, 1 mg riboflavin, 1 mg pyridoxine hydrochloride, 1 mg thiamine hydrochloride, 3 mg Ca pantothenate, 20 μg biotin, 90 μg folic acid, 1.4 μg cyanocobalamin; ICN Pharmaceuticals, Cleveland, OH, U.S.A.), and 20.0 mineral mix (containing per gram of mix 300 mg monocalcium phosphate, 80 mg calcium carbonate, 158 mg potassium chloride, 138 mg sodium bicarbonate, 24 mg magnesium sulfate, 3 mg zinc sulfate, 1.1 mg ferrous sulfate, 1 mg cobalt carbonate, 0.9 mg manganese sulfate, 0.6 mg cuprous sulfate, 16.5 μg potassium iodide; ICN Pharmaceuticals, Cleveland, OH, U.S.A.).

In vivo protein synthesis determinations.

Each piglet was administered via the umbilical artery catheter a single dose (10 mL/kg body weight) of a sterile solution of l-phenylalanine (150 mM) containing l-[4-3H]phenylalanine (3.7 Mbq/mL; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.). Blood samples were collected 5, 15, and 30 min after the injection. After the last blood sample was taken, the piglets were anesthetized, exsanguinated, and a sample of one longissimus dorsi muscle was removed rapidly and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Muscle protein fractionation.

The frozen muscle from each piglet was powdered in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in a low-ionic-strength buffer. A sample of homogenate was retained for total protein (8) and RNA concentration (9) measurements. The sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar components were isolated using a modification (10) of the method of Solaro et al. (11). Proteins soluble in low-ionic-strength buffer after high-speed centrifugation (15,000 ×g at 2oC for 45 min) were defined as the sarcoplasmic proteins.

Determination of [4-3H]phenylalanine specificradioactivity.

The acid-insoluble protein precipitates of the various muscle protein fractions and blood samples were hydrolyzed to free amino acids in 6 M HCl. Phenylalanine in the neutralized homogenate and blood supernatants and the hydrolysates of the total, sarcoplasmic, and myofibrillar proteins was isolated by anion exchange HPLC as described previously (10). Amino acids were postcolumn derivatized with orthophthalaldehyde reagent and detected fluorimetrically. The phenylalanine concentration was determined by comparison to a known standard. The eluted fraction containing the phenylalanine peak was collected, and the associated radioactivity was determined.

Isolation and quantification of mRNA and rRNA.

Total RNA was extracted from the powdered muscle with Ultraspec (12) (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, TX, U.S.A.). The extracted RNA was dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water, and the concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm. Ten-microgram aliquots of RNA were fractionated on a 1% agarose/0.66 M formaldehyde gel. The integrity of the RNA was established from the presence of intact 28S and 18S rRNA bands in a ratio of approximately 2:1 after ethidium bromide staining. The RNA was transferred to a nylon membrane by capillary action and UV cross-linked to the membrane for subsequent Northern analyses.

For each muscle, 0.25- and 0.50-μg (each in duplicate) RNA aliquots also were applied to nylon membranes for slot blot analysis. On each membrane, a set of polyA RNA (1 to 4 ng; Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX, U.S.A.) and 18S rRNA (5 to 25 ng) standards and a skeletal muscle RNA control from 7-d-old piglets were applied. The 18S rRNA standard was generated by in vitro transcription of a 616-base cDNA to rat 18S rRNA (13) subcloned into the pBluescript SK vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.); all ribonucleotides were added in equimolar amounts and were nonradioactive but for a trace quantity of 3H-UTP for accurate quantification. Full-length transcripts were obtained by gel purification. A factor of 3.04 was used to calculate the absolute mass of 18S rRNA, based on the mass equivalence of a mole of standard and a mole of the full-length 18S rRNA transcript.

The Northern membranes were probed simultaneously for GAPDH and MHC mRNA, and the slot blots were probed sequentially for MHC mRNA, polyA RNA, and 18S rRNA. DNA probes were generated by random prime labeling (14) using the following templates: pTRI-GAPDH-rat (Ambion, Austin, TX, U.S.A.); a 407-bp fragment of human perinatal MHC from a highly conserved segment in the rod and that cross-hybridizes with all sarcomeric MHC (15) (kindly provided by Dr. Leslie Leinwand, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, U.S.A.); and the same rat 18S rRNA template described above. A 32P-labeled poly(dT) probe was generated by reverse transcription of the polyA template (14). Membranes were prehybridized and hybridized for Northern and polyA analyses (14). Posthybridization washing conditions were optimized for each probe; Northern blots of the control RNA were processed with each slot blot membrane to verify that slot blots were appropriately washed. The 32P signal intensity associated with each band was quantified using a PhosphoImager and associated software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.).

Calculations.

Protein FSR (percent of protein mass synthesized per day) was calculated as follows:MATH where SB is the specific radioactivity of the protein-bound phenylalanine, SFP is the mean specific radioactivity of the muscle-free phenylalanine for the labeling period (6), and t is the time of labeling in minutes. We have demonstrated that the specific radioactivity of the muscle-free phenylalanine, after it is administered as a flooding dose, is in equilibrium with the amino-acyl transfer RNA-specific radioactivity and, therefore, provides an equally valid measure of FSR (16). Ribosome translational efficiency was calculated as grams of protein synthesized per day per microgram of 18S rRNA.

Dose-response curves were generated from the polyA RNA and 18S rRNA standards and used to interpret the intensity of the signals from the muscle RNA samples; MHC data were expressed in terms of pixels. Blot-to-blot variations were corrected on the basis of the values derived for the control RNA samples. Values were expressed per microgram of total RNA loaded and per milligram of muscle protein using the value for the ratio of total RNA to protein derived from the same muscle.

Statistical analyses.

Values are expressed as mean ± 1 SEM. The effect of feeding group on the various parameters assessed was analyzed by ANOVA using a general linear model (MINITAB, version 12.21, State College, PA, U.S.A.) with protein compartment, i.e. sarcoplasmic or myofibrillar protein, as a repeated measure. Interactions were evaluated, and differences between groups were tested post hoc by F test with a Fisher least significant difference adjustment for multiple comparisons.

We evaluated statistically the extent to which variations in muscle rRNA and mRNA (total and MHC) abundance and plasma insulin, IGF-I, and amino acids (total, essential, or branched chain) contributed to the differences in FSR among groups by determining whether a feeding group effect would account for any of the residual variance after controlling for the variance attributable to RNA, hormones, and substrates. Regression analysis was performed against total, sarcoplasmic, and myofibrillar protein FSR in fed piglets.

RESULTS

Protein and energy intakes over 24 h of colostrum- and formula-fed piglets were similar and significantly higher than those of the mature milk-fed animals (Table 1). These differences were reflected in the higher plasma insulin and essential amino acid concentrations (Table 1). However, the increases in plasma nonessential amino acids (not shown), glucose (not shown), and IGF-I were similar among fed groups. Plasma insulin concentrations correlated more highly with plasma total amino acid concentration (r = 0.73;p < 0.001) than with glucose (r = 0.33;p < 0.05).

Skeletal muscle protein FSR.

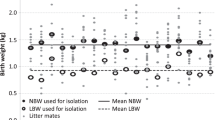

Feeding resulted in a 2.5- to 3-fold increase in total protein FSR (Fig. 1), which was 28% greater when colostrum was fed rather than formula or mature milk (p < 0.001). There was no difference between the formula- and mature milk-fed piglets despite their widely disparate nutrient intakes. The greater stimulation in the colostrum-fed pigs was attributable entirely to the increase in myofibrillar FSR (+39%), as the FSR of the sarcoplasmic compartment was similar among all fed groups. Hence, the ratio of myofibrillar to sarcoplasmic proteins synthesized was higher in the colostrum-fed piglets (1.15 ± 0.05) than in either formula- or milk-fed (0.90 ± 0.01) or unfed piglets (0.80 ± 0.02) (p < 0.001).

Fractional synthesis rates of total, sarcoplasmic, and myofibrillar proteins in the skeletal muscle of newborn piglets after being fed for 24 h with sow's mature milk (n = 5), formula (n = 5), or colostrum (n = 5) compared with piglets given water only (unfed, n = 4). Values are mean ± 1 SEM. Values with different superscripts are significantly different, p < 0.05.

rRNA abundance and translational efficiency.

Feeding increased 18S rRNA abundance, and the increase was greatest in the colostrum-fed piglets (Table 2). In all groups, this rise in ribosome abundance was accompanied by an increase in their translational efficiency, although the efficiency attained was similar regardless of diet composition. Thus, the increase in ribosome abundance in the colostrum-fed piglets was crucial to the overall increase in skeletal muscle FSR. Again, differences between formula- and mature milk-fed piglets in rRNA abundance were not significant despite their disparate intakes. Because rRNA is the predominant component of total RNA, similar results were obtained when total RNA concentrations rather than 18S rRNA were used to estimate translational efficiency.

mRNA abundance.

PolyA concentration (ng/mg muscle protein) provides a measure of the total translatable cytoplasmic mRNA. Feeding resulted in an average 3-fold increase in the concentration of polyA. Relative to protein content, the increase was greatest for the formula-fed piglets, intermediate for colostrum-fed piglets, and least for the mature milk-fed group (Table 3). Indeed, among the fed groups, there was a strong correlation between plasma branched-chain amino acid and muscle polyA concentrations (r = 0.62;p < 0.02).

In a previous study, we showed that the FSR of myofibrillar proteins in immature skeletal muscle quantitatively reflects that of the MHC component (10). Thus, we measured the relative abundance of MHC mRNA to determine whether it could account for the observed differences in the composition of muscle proteins synthesized. The cDNA used is homologous to the C-terminal coding region of human perinatal MHC, a sequence that is highly conserved across all sarcomeric MHC (15), so that the estimates of MHC mRNA abundance reflect the sum of all immature and fast isoforms present. The abundance of MHC mRNA relative to both the total polyA content and to a nonmuscle-specific mRNA (GAPDH) was greatest in the colostrum-fed and unfed piglets. The relative proportion of MHC mRNA did not change with feeding colostrum, even though there was an approximately 3-fold increase in polyA concentration. However, when either mature milk or formula was fed, there was a reduction in the relative abundance of MHC mRNA despite the increase in total polyA, suggesting that, in these groups, the stimulation of mRNA accretion apparently selected against MHC mRNA.

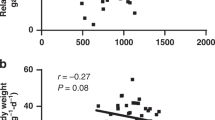

No significant correlations between plasma hormone or substrate concentrations and tissue mRNA concentration or protein synthesis rates could be identified. Differences in total protein FSR among feeding groups were attributable only to the variation in ribosomal abundance (mg rRNA/g total protein) (r2 = 0.40 ; p < 0.005). We could identify no variable that would explain the variance in sarcoplasmic protein FSR, whereas both ribosomal abundance and MHC mRNA [pixels mRNA/μg polyA] contributed to the variance in myofibrillar protein FSR (r2 = 0.64;p < 0.001) and did so independently of each other.

DISCUSSION

In previous work, we found that the enhanced stimulation of skeletal muscle protein synthesis in newborn piglets fed colostrum as opposed to other feeds is not due solely to the provision of nutrients (5, 6). The primary objective of the present study was to identify which components of the protein synthetic pathway respond specifically to colostrum feeding. The results suggest that there are two components to the anabolic effect of feeding colostrum: a quantitative one and a qualitative one. First, there was the general stimulation of protein synthesis by feeding regardless of diet that resulted from an increase in the abundance and translational efficiency of muscle ribosomes. This incurred a proportional stimulation in the synthesis of both sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar proteins. However, colostrum augmented the effect of feeding by promoting a more marked accretion of ribosomes. Second, in the colostrum-fed piglets, the enhanced synthesis rate was specifically restricted to the myofibrillar proteins and reflected a disproportionate increase in the abundance of myofibrillar mRNA, as exemplified by MHC mRNA.

Ribosomal abundance and translational efficiency.

The primary anabolic effect of colostrum feeding was an increase in muscle ribosomal abundance. Other circumstances in which significant changes in ribosomal abundance have been related to alterations in skeletal muscle protein accretion and synthesis include the following:1) the maturation from myotube to myofiber during normal development when there is a reduction in ribosome concentration (10), a change that is likely due to a fall in the rate of rRNA synthesis (17);2) the changes after stretch-induced muscle hypertrophy when a rapid increase in rDNA transcription initiates the muscle hypertrophic response (18); and 3) the response to increases in circulating hormones such as thyroid and GH (19, 20).

Although the magnitude of the ribosomal accretion response to feeding was influenced by the composition of the diet, the increase in ribosomal translational efficiency was not. We have shown previously that the FSR of mixed muscle proteins in the neonate is highly sensitive to food intake and is mediated in large part by insulin (21, 22). On the basis of the relationship between plasma insulin concentration and FSR in the immature muscle (23), maximal translation rates would be anticipated even at the lower insulin concentration attained by the mature milk-fed piglets. These findings suggest that there is a maximal rate of translation that ribosomes can achieve and that this rate was achieved by all fed piglets regardless of any metabolic differences incurred by the three feeding regimens. Thus, it was the increase in ribosome abundance rather than their translational efficiency that enabled the colostrum-fed piglets to enhance their synthesis rate further than that achieved by those fed mature milk or formula.

Total polyA abundance.

Feeding also resulted in the rapid increase in the steady state abundance of polyA mRNA (150 to 250%), an increase that was greatest in the formula-fed and least in the mature milk-fed piglets. The increase in polyA abundance was correlated positively with plasma essential amino acid concentrations, underscoring the capacity of amino acids to regulate gene expression as has been demonstrated in the liver (24). However, the difference in protein synthesis between the formula- and colostrum-fed groups showed that the differences in the total abundance of polyA did not necessarily alter protein synthesis rates. Indeed, the efficiency with which total mRNA was translated, expressed as milligram of total muscle protein synthesized per microgram of polyA, was significantly lower in the formula-fed group in which polyA abundance was the highest. This observation highlights the fact that once skeletal muscle differentiation approaches completion, ribosome abundance rather than total mRNA abundance primarily determines the maximal capacity for protein synthesis.

Myofibrillar protein synthesis rates.

The second effect of feeding colostrum was a specific stimulation in myofibrillar protein synthesis. There are other instances in which there is a discoordinated response of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic proteins. These include both the period of myofiber maturation as well as the aging process, during both of which there is a disproportionate down-regulation in myofibrillar protein FSR (10, 25). In addition, in adult rodents, myofibrillar protein synthesis rates are more sensitive than sarcoplasmic proteins to variations in food intake (26, 27), although our observations in this and a previous report (10) indicate that this may not necessarily be true in very young animals. Reports on the separate responses of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic protein synthesis and accretion to a variety of hormones such as plasma insulin (our unpublished observations), glucocorticoids (28), androgens (29), IGF-I (30), and β-adrenergic agonists (31) have described proportional responses of the two compartments. The effect of muscle work on sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar proteins varies with age and fiber type. In young rats, there is a proportional decrease in sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar protein synthesis rates upon muscle unloading (32), whereas overloading fast-twitch muscles results in a proportional increase in their synthesis rates (33). Thus, our results are unique in that they implicate the presence of a factor in colostrum that can acutely induce an increase in the translational capacity and alter the composition of proteins synthesized by the muscle.

MHC mRNA abundance.

One possible explanation for the increase in myofibrillar protein synthesis is that a maternally derived factor(s) transmitted via the mammary gland results in the increased transcription and/or stabilization of messages that encode specifically the myofibrillar proteins such as MHC mRNA. Thus, the abundance of muscle-specific mRNA relative to other mRNA in the muscle increases, which then enhances their likelihood of being translated relative to nonmuscle-specific mRNA. The lower MHC mRNA abundance in the mature milk-fed piglets suggests that the production of this factor decreases after parturition and presumably was absent in the formula.

Neuromuscular development in the pig at birth is fairly advanced, and, thus, the observed responses must involve cellular pathways that are active in the differentiated muscle. However, as we noted above, most stimuli or inhibitors of growth in mature muscle do not affect the synthesis of myofibrillar proteins exclusively. It seems likely, therefore, that any factor involved is most active in the differentiated muscle but at a time before the muscle has attained its stable mature composition. Possible candidates are the bHLH/myoD family of transcription factors, myoD and myogenin specifically (34), and those proteins that can modulate their activity (35–38). It is of interest that in addition to skeletal muscle, the principal tissues in which MEF2 and serum response factor are expressed are those same tissues in which the stimulation of protein synthesis was enhanced by feeding colostrum, i.e. the heart, neural tissues including the brain, and tissues containing smooth muscle (such as in the serosal layer of the intestine). The regulation of the expression of these factors by externally initiated signals has not been clearly defined. However, in two instances of enhanced muscle growth, weight-induced muscle hypertrophy and muscle regeneration, an increase in the activity of these factors appears to be an essential component of the anabolic response (39–41). The abundance of myogenic factors also responds to many of those same variables that regulate ribosomal abundance, and, thus, their increase may have been effected by the same stimulus.

Colostral factors.

Although at this time the nature of the colostral factor is unknown, the present observations enable us to define some of its characteristics. It should be more concentrated in colostrum than in mature milk and retain its bioactivity as it passes through the digestive tract. It is probably absorbable, although we cannot exclude the possibility that an interaction between colostrum and the intestine generates a humoral signal that is responsible for eliciting the observed effects. The substance(s) also must act specifically on skeletal muscle and potentially on cardiac muscle, brain, and the jejunum, or it could elicit the production of endogenous factors that target those same tissues. Finally, the effect on skeletal muscle must be to increase ribosomal abundance and enhance muscle-specific gene expression. Although these properties narrow down the potential field of candidates, it is probably fair to say that, at this point, we can only exclude a number of potential factors.

Notwithstanding the high concentrations of insulin and IGF-I in colostrum and their decrease in concentration as lactation proceeds, it is unlikely that they induced the observed responses. Neither hormone apparently is absorbed in significant amounts in the pig (5, 42, 43), and the observed muscle responses were not related to the differences in plasma concentrations of the hormones among feeding groups. Moreover, we (our unpublished observations) and Adams and McCue (30) also have observed that although insulin and IGF can stimulate muscle protein synthesis in the neonate, the increase is equivalent for myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic proteins. Although thyroid hormones are present in colostrum (44) and could elicit the observed responses, differences in thyroid hormone are unlikely to have produced the observed differences among groups. Within the first 24 h of life, there is a postnatal surge in all thyroid hormones that occurs regardless of whether colostrum or a semisynthetic formula is fed to piglets (44). Additionally, the piglet demonstrates a rapid postprandial surge in both thyroxine and triiodothyronine, but the magnitude is dependent on the level of energy intake and this was, by design, similar for colostrum- and formula-fed piglets (45). An androgenic or GH effect also can be excluded because neither their absence nor presence alters muscle protein synthesis in newborn pigs (46, 47). Studies of the separate responses of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic protein synthesis to a variety of hormones, as noted previously, have recorded proportional responses of the two compartments. There are a variety of additional factors that are present in significantly higher levels in swine colostrum than in mature milk, including epidermal growth factor, estrogens, and prolactin (48, 49). However, the tissue specificity of these factors in the neonate and their effect on the regulation of ribosomal and muscle-specific gene expression are not well characterized.

Significance.

These data show that feeding colostrum not only has quantitative consequences for the anabolic processes in the skeletal musculature of the newborn infant but also qualitative ones, with potential implications for the development of muscle function. Improvement of skeletal muscle function is advantageous insofar as it is critical for the development of the newborn's ability to survive independently from its mother. The effects observed are likely attributable to nonnutritive factors present in colostrum and possibly in mature milk, albeit at lower concentrations. The identification of the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon, particularly the relative importance of increased RNA synthesis and stability, will be critical not only for advancing our understanding of the biologic role of early mammary secretions in the regulation of neonatal growth but also in establishing how diet contributes to the regulation of skeletal muscle growth in early postnatal life.

Abbreviations

- FSR:

-

fractional synthesis rate

- MHC:

-

myosin heavy chain

- GAPDH:

-

glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- polyA:

-

polyadenylated RNA

- rRNA:

-

ribosomal RNA

References

Widdowson EM, Crabb DE 1976 Changes in the organs of pigs in response to feeding for the first 24 h after birth. Biol Neonate 28: 261–271

Widdowson EM, Colombo VE, Artavanis CA 1976 Changes in the organs of pigs in response to feeding for the first 24 h after birth. Biol Neonate 28: 272–281

Heird WC, Schwarz SM, Hansen IH 1984 Colostrum-induced enteric mucosal growth in beagle puppies. Pediatr Res 18: 512–515

Berseth CL, Lichtenberger LM, Morris FH 1983 Comparison of growth-promoting effects of rat colostrum and mature milk in newborn rats in vivo. Am J Clin Nutr 37: 52–60

Burrin DG, Davis TA, Ebner S, Schoknecht PA, Fiorotto ML, Reeds PJ, McAvoy S 1995 Nutrient-independent and nutrient-dependent factors stimulate protein synthesis in colostrum-fed newborn pigs. Pediatr Res 37: 593–599

Burrin DG, Davis TA, Ebner S, Schoknecht PA, Fiorotto ML, Reeds PJ 1997 Colostrum enhances the nutritional stimulation of vital organ protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. J Nutr 127: 1284–1289

Jeejeebhoy KN, Ahmad S, Kozak G 1970 Determination of fecal fats containing both medium and long chain fatty acids. Clin Biochem 3: 157–163

Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ 1951 Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275

Munro HN, Fleck A 1966 Recent developments in the measurement of nucleic acids in biological materials. Analyst 91: 78–88

Fiorotto ML, Davis TA, Reeds PJ 2000 Regulation of myofibrillar protein turnover during maturation in normal and undernourished rat pups. Am J Physiol 278: R845

Solaro RJ, Pang DC, Briggs FN 1971 The purification of cardiac myofibrils with Triton-X100. Biochim Biophys Acta 245: 259–262

Chomczynski P, Sacchi N 1987 Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162: 156–159

Rothblum LI, Parker DL, Cassidy B 1982 Isolation and characterization of rat ribosomal DNA clones. Gene 17: 74–77

Farrell RE 1993 RNA Methodologies: A Laboratory Guide for Isolation and Characterization. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 47–202

Feghali R, Leinwand LA 1987 Molecular genetic characterization of a developmentally regulated human perinatal myosin heavy chain. J Cell Biol 108: 1791–1797

Davis TA, Fiorotto ML, Nguyen HV, Burrin DG 1999 Aminoacyl t-RNA and tissue free amino acid pools are equilibrated after a flooding dose of phenylalanine. Am J Physiol 277: E103

Jacobs FA, Bird RC, Sells BH 1985 Differentiation of rat myoblasts. Eur J Biochem 150: 255–263

Goldspink DF, Cox VM, Smith SK, Eaves LA, Obsaldeston NJ, Lee DN, Mantle D 1995 Muscle growth in response to mechanical stimuli. Am J Physiol 268: E288

Flaim KE, Li JB, Jefferson LS 1978 Effects of thyroxine on protein turnover in rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol 235: E231

Pell JM, Bates PC 1987 Collagen and non-collagen protein turnover in skeletal muscle of growth hormone-treated lambs. J Endocrinol 115: R1

Davis TA, Burrin DG, Fiorotto ML, Nguyen HV 1996 Protein synthesis in skeletal muscle and jejunum is more responsive to feeding in 7- than 26-day-old pigs. Am J Physiol 270: E802

Wray-Cahen D, Nguyen HV, Burrin DG, Beckett PR, Fiorotto ML, Reeds PJ, Wester TJ, Davis TA 1998 Response of skeletal muscle protein synthesis to insulin in suckling pigs decreases with development. Am J Physiol 275: E602

Davis TA, Burrin DG, Fiorotto ML, Reeds PJ, Jahoor F 1998 Roles of insulin and amino acids in the regulation of protein synthesis in the neonate. J Nutr 128: 347S–350S

Marten NM, Burke EJ, Hayden JM, Straus DS 1994 Effect of amino acid limitation on the expression of 19 genes in rat hepatoma cells. FASEB J 8: 538–544

Balagopal P, Rooyackers OE, Adey DB, Ades PA, Nair KS 1997 Effects of aging on in vivo synthesis of skeletal muscle myosin heavy-chain and sarcoplasmic protein in humans. Am J Physiol 273: E790

Preedy VR, Sugden PH 1989 The effects of fasting or hypoxia on rates of protein synthesis in vivo in subcellular fractions of rat heart and gastrocnemius muscle. Biochem J 257: 519–527

Svanberg E, Zachrisson H, Ohlsson C, Iresjö BM, Lundholm KG 1996 Role of insulin and IGF-I in activation of muscle protein synthesis after oral feeding. Am J Physiol 270: E614

Hickson RC, Czerwinski SM, Wegrzyn LE 1995 Glutamine prevents downregulation of myosin heavy chain synthesis and muscle atrophy from glucocorticoids. Am J Physiol 268: E730

Brodsky IG, Balagopal P, Nair KS 1996 Effects of testosterone replacement on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis in hypogonadal men–a research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 3469–3475

Adams GR, McCue SA 1998 Localized infusion of IGF-I results in skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol 84: 1716–1722

Hesketh JE, Campbell GP, Lobley GE, Maltin CA, Acamovic F, Palmer RM 1992 Stimulation of actin and myosin synthesis in rat gastrocnemius muscle by clenbuterol; evidence for translational control. Comp Biochem Physiol 1 C 102: 23–27

Munoz KA, Satarug S, Tischler ME 1993 Time course of the response of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic protein metabolism to unweighting of the soleus muscle. Metabolism 42: 1006–1012

Gregory P, Gagnon J, Essig DA, Reid SK, Prior G, Zak R 1990 Differential regulation of actin and myosin isoenzyme synthesis in functionally overloaded skeletal muscle. Biochem J 265: 525–532

Schwarz JJ, Martin JM, Olson EN 1993 Transcription factors controlling muscle-specific gene expression. In: Karin M (ed) Gene Expression: General and Cell-type Specific. Birkhauser, Boston, pp 93–115

Molkentin JD, Olson EN 1996 Combinatorial control of muscle development by basic helix-loop-helix and MADS-box transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9366–9373

Kong Y, Flick MJ, Kudla AJ, Konieczny SF 1997 Muscle LIM protein promotes myogenesis by enhancing the activity of MyoD. Mol Cell Biol 17: 4750–4760

Carnac G, Primig M, Kitzmann M, Chafey P, Tuil D, Lamb N, Fernandez A 1998 RhoA GTPase and serum response factor control selectively the expression of MyoD without affecting Myf5 mouse myoblasts. Mol Biol Cell 9: 1891–1902

Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Davis DL, Weintraub H 1990 The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell 61: 49–59

Marsh DR, Carson JA, Stewart LN, Booth FW 1998 Activation of the skeletal alpha-actin promoter during muscle regeneration. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 19: 897–907

Carson JA, Schwartz RJ, Booth FW 1996 SRF and TEF-1 control of chicken skeletal alpha-actin gene during slow-muscle hypertrophy. Am J Physiol 270: C1624

Carson JA, Booth FW 1998 Myogenin mRNA is elevated during rapid, slow, and maintenance phases of stretch-induced hypertrophy in chicken slow-tonic muscle. Pflugers Arch 435: 850–858

Burrin DG, Davis TA, Fiorotto ML, Reeds PJ 1997 Role of milk-borne vs endogenous insulin-like growth factor I in neonatal growth. J Anim Sci 75: 2739–2743

Shulman RJ 1990 Oral insulin increases small intestinal mass and disaccharidase activity in the newborn miniature pig. Pediatr Res 28: 171–175

Šlebodzi˘nski AB, Cogiel F 1983 Serum thyroid hormone levels in colostrum deprived piglets and calves. Endocrinol Exp 17: 263–270

Dauncey MJ, Morovat A 1993 Investigation of mechanisms mediating the increase in plasma concentrations of thyroid hormones after a meal in young growing pigs. J Endocrinol 139: 131–141

Skjaerlund DM, Mulvaney DR, Bergen WG, Merkel RA 1994 Skeletal muscle growth and protein turnover in neonatal boars and barrows. J Anim Sci 72: 315–321

Wester TJ, Davis TA, Fiorotto ML, Burrin DG 1998 Exogenous growth hormone stimulates somatotropic axis function and growth in neonatal pigs. Am J Physiol 274: E29

Jaeger LA, Lamar CH, Bottoms GD, Cline TR 1987 Growth-stimulating substances in porcine milk. Am J Vet Res 48: 1531–1533

Farmer C, Houtz SK, Hagen DR 1987 Estrone concentration in sow milk during and after parturition. J Anim Sci 64: 1086–1089

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Karen Clare and Monica Puppi for technical assistance. We also thank Dr. E. O'Brian Smith for his assistance with statistical analyses and Leslie Loddeke for editorial assistance.

We wish to take the opportunity to pay tribute to the late Dr. Elsie M. Widdowson CH, CBE, FRS, whose pioneering work on the properties of colostrum was the driving force behind this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service under Cooperative Agreement number 58–6250-6001.

The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fiorotto, M., Davis, T., Reeds, P. et al. Nonnutritive Factors in Colostrum Enhance Myofibrillar Protein Synthesis in the Newborn Pig. Pediatr Res 48, 511–517 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200010000-00015

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-200010000-00015

This article is cited by

-

Short- and long-term effects of leucine and branched-chain amino acid supplementation of a protein- and energy-reduced diet on muscle protein metabolism in neonatal pigs

Amino Acids (2018)

-

Leucine supplementation of a chronically restricted protein and energy diet enhances mTOR pathway activation but not muscle protein synthesis in neonatal pigs

Amino Acids (2016)