Abstract

Background:

Guidelines recommend regular use of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-containing medications for all patients with persistent asthma and those with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. It is important to identify indicators of inappropriate prescribing.

Aims:

To test the hypothesis that ICS are prescribed for the management of respiratory infections in some patients lacking evidence of chronic airways disease.

Methods:

Medication dispensing data were obtained from the Australian national Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for concessional patients dispensed any respiratory medications during 2008. We identified people dispensed only one ICS-containing medication and no other respiratory medications in a year, who were therefore unlikely to have chronic airways disease, and calculated the proportion who were co-dispensed oral antibiotics.

Results:

In 2008, 43.6% of the 115,763 patients who were dispensed one-off ICS were co-dispensed oral antibiotics. Co-dispensing was seasonal, with a large peak in winter months. The most commonly co-dispensed ICS among adults were moderate/high doses of combination therapy, while lower doses of ICS alone were co-dispensed among children. In this cohort, one-off ICS co-dispensed with oral antibiotics cost the government $2.7 million in 2008.

Conclusions:

In Australia, many people who receive one-off prescriptions for ICS-containing medications do not appear to have airways disease. In this context, the high rate of co-dispensing with antibiotics suggests that ICS are often inappropriately prescribed for the management of symptoms of respiratory infection. Interventions are required to improve the quality of prescribing of ICS and the management of respiratory infections in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), either alone or in combination with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA), are very effective for preventing many of the adverse outcomes of chronic airways disease, reducing mortality and morbidity in persistent asthma,1–3 and reducing the incidence of exacerbations in people who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with a history of frequent exacerbations.4,5 For these reasons, regular treatment with ICS is recommended in international and national guidelines6–9 for many patients with asthma and for some patients with COPD. These medications are commonly prescribed for chronic airways disease in many countries, including Australia, the UK, and the USA.

Medications prescribed by general practitioners are often subsidised by the government. For example, in the UK many patients are exempt from the cost of prescription medications through the National Health Service; in 2010, prescriptions provided free of charge represented approximately 94% of all items dispensed in England.10 In Australia the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) currently subsidises some or all of the cost of approximately 80% of prescription medications dispensed.11 Since both asthma and COPD are common diseases and ICS are reimbursed for these conditions, medications prescribed for chronic airways disease represent a substantial cost to the government. In 2010–11, salmeterol/fluticasone was listed as the sixth highest drug by cost to the Australian government.12 Prescription pharmaceuticals account for a large proportion of total health expenditure and, in Australia, this accounted for 59% of the total health expenditure for asthma.13 Furthermore, adverse effects of ICS have been reported.14,15 It is therefore important that appropriate prescribing is encouraged and indicators of inappropriate prescribing are identified.

We have recently shown that, in Australia, most people who are dispensed ICS are only dispensed one ICS-containing medication in any given year.13 However, there is no evidence that a short course of this therapy is effective for any specific condition (other than for chronic cough due to eosinophilic bronchitis16), and guidelines for the use of ICS in asthma and COPD recommend that ICS — where indicated — should be used regularly.8,9 While some of the observed irregular dispensing may be due to poor adherence by patients who were prescribed this class of medication for regular use, anecdotal reports from pharmacists and patients suggest that ICS are sometimes being co-prescribed with antibiotics for treatment of respiratory tract infections.

The primary aim of our study was to investigate whether ICS are being prescribed for the treatment of respiratory tract infections in people without evidence of chronic airways disease. A second aim was to identify risk factors for this apparently inappropriate use of ICS.

Methods

The study was conducted using anonymous linkage within the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme dataset. Ethical approval to conduct the project was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

The study cohort was defined within the PBS dataset for the 2008 calendar year based on the use of specific medications and beneficiary status of the patient. The PBS dataset includes the medication name and dose, dispensing date and beneficiary status (general or concession), and 5-year age group, sex, and residential postcode. Medication records are linked to individuals using an encrypted patient identification number.

The study cohort for this analysis was limited to holders of concession cards to ensure that a complete medication record was available. Until very recently, data were only recorded on the PBS database for eligible items for which the cost exceeded a specified co-payment threshold and a subsidy was provided. Since the co-payment threshold for general beneficiaries exceeded the cost of some respiratory medications and antibiotics, these classes of medications were only fully captured for concessional beneficiaries. Concession cards are available to people receiving government benefits such as unemployment and sickness benefits, and for repatriation (veterans') benefits.

The study cohort comprised all concession card holders who, in 2008, were dispensed any respiratory medication — that is, ICS (either alone or in combination with LABA), LABA (either alone or in combination with ICS), short-acting β2-agonists, long-acting or short-acting anticholinergic drugs, leukotriene receptor antagonists, methyl xanthines including theophylline, or cromones. In general, one dispensing of these medications will provide sufficient medication for one month's treatment at standard doses.

We identified a sub-group who had a single episode of dispensing of ICS-containing medication in the 2008 calendar year and no other respiratory medications dispensed within ±6 months of this date except within ±7 days of the incident date (hereafter called ‘one-off’ dispensing of ICS). The exception of ±7 days of the incident date was allowed as other dispensing of respiratory medications within this short time window may have been for the same clinical event. Co-dispensing of antibiotics was defined as dispensing of oral antibiotics within ±7 days of the date of one-off dispensing of ICS. Antibiotics dispensed with six months’ supply were assumed to be for long-term use and were excluded.

Data analysis

The number of people dispensed one-off ICS was calculated, together with the number and proportion of these who were co-dispensed antibiotics. The weekly incidence of co-dispensing was displayed by age groups for adults and children to describe seasonal patterns. Co-dispensing rates were reported for the whole cohort and for subgroups classified according to age, sex, socio-economic status (based on the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage, one of the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA)17), and geographical location (based on the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC)18).

The relationship between antibiotic use and demographic factors including age, sex, socioeconomic status, and remoteness of residence was described using rate ratios (RR). These were estimated using a generalised linear model with a binomial distribution in SAS Proc Genmod (SAS v9.2).

The cost to the Australian government of one-off ICS when co-dispensed with antibiotics was calculated by subtracting the concessional co-payment by the patient ($5.00 in 2008) from the total cost of each of the ICS drugs as listed in the 2008 PBS schedule and multiplying by the number of one-off prescriptions dispensed for each of the ICS drugs.

Results

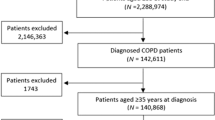

In 2008 approximately 64% of Australians receiving respiratory medications through the PBS received them at the concessional rate. In that year, 695,732 patients with a concession card were dispensed any ICS medication (Figure 1). Of these, 33% were dispensed a single prescription for ICS, and 50.4% of these (115,763) were dispensed no other respiratory medication during the six months before or after this date (‘one-off’ ICS). Of the concession card holders who had only one ICS prescription in 2008 and no other respiratory medication, 50,512 (43.6%) were co-dispensed oral antibiotics (i.e. were dispensed an oral antibiotic within ±7 days of the one-off ICS).

The medications were dispensed on the same day for most (70%) individuals who were co-dispensed one-off ICS and oral antibiotics while, for 22.5%, the antibiotic was dispensed 1–7 days before the one-off ICS (Figure 2). The remaining 7.5% were dispensed oral antibiotics 1–7 days after the one-off ICS.

Among people dispensed one-off ICS in 2008, slightly more females (45.0%) than males (41.5%) were co-dispensed oral antibiotics (relative risk 1.08, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.10). Co-dispensing of oral antibiotics was more common in adults than children and in people living in major cities than in people living in other areas, but did not differ according to socioeconomic status (Table 1).

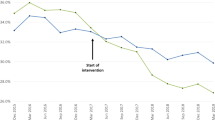

Co-dispensing of one-off ICS and oral antibiotics was seen throughout the year, but was primarily a late winter/early spring phenomenon in people aged ≥5 years. In young children (aged 0–4 years) the incidence of co-dispensing peaked earlier, in June (Figure 3).

The most common Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classes of oral antibiotics co-dispensed with one-off ICS were beta-lactam antibacterials/penicillins (44%, including 25.7% for amoxicillin) and macrolides/lincosamides and streptogramins (34%, including 22% for roxithromycin). These antibiotics are commonly used for the treatment of respiratory tract infections.

The majority (77%) of one-off ICS prescriptions co-dispensed with oral antibiotics were dispensed as combination ICS/LABA therapy. Furthermore, moderate- or high-dose combination ICS/LABA formulations accounted for 70.3% of all one-off co-dispensed ICS prescriptions (Table 2). Children were most commonly co-dispensed ICS at lower doses and as ICS alone, particularly those aged 0–4 years. One-off ICS dispensed as ICS alone accounted for 69% of ICS prescriptions dispensed in children aged 0–4 years (of which 88% were the lowest doses) and 38% of those in children aged 5–14 years (of which 60% were the lowest doses). For adult concession card holders, most (around 80%) of the one-off ICS were dispensed as combined formulations of ICS/LABA. Adults were most commonly dispensed the moderate/high-dose formulations of ICS (data not shown).

The cost to the Australian government of ICS dispensed as one-off prescriptions to concessional beneficiaries, when accompanied by co-dispensing of oral antibiotics, was approximately $2.7 million (Table 2). Prescriptions for salmeterol/fluticasone accounted for almost half of this cost (20,296 prescriptions; $1,274,023.98), followed by budesonide/eformoterol (18,393 prescriptions;

$1,074,822.12) (Table 3). More than half (52.9%) of the one-off salmeterol/fluticasone prescriptions co-dispensed with oral antibiotics were the highest doses available compared with 18.9% for budesonide/eformoterol (data not shown). These costs exclude the cost to patients of the co-payment and the cost of the antibiotic itself.

Discussion

Main findings

Despite the known effectiveness of ICS medications in chronic airways disease, particularly in asthma, there is increasing awareness that ICS dispensing is substantially less than is consistent with regular daily usage. To date, attention has primarily focused on poor adherence by patients. However, the findings of this study suggest that ICS are also being prescribed in Australia for people without chronic airways disease, as indicated by the lack of dispensing of any other respiratory medications — not even short-acting β2-agonist reliever — within 12 months. This pattern was seen for half of the concession card holders who had a single ICS prescription in 2008. The finding that 44% of these patients were co-dispensed their single ICS with an oral antibiotic suggests that the ICS were being prescribed inappropriately as treatment for symptoms of respiratory tract infection.

Several findings in the analysis support this theory. First, the co-prescribing phenomenon was strongly seasonal, with a late winter peak. This is the time of year when respiratory viruses are most frequently isolated19 and respiratory tract infections20 are most frequently observed. For example, in data from an influenza surveillance programme and from patients hospitalised with a respiratory illness in Victoria, Australia in 2002 and 2003, winter peaks were seen in respiratory syncytial virus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza and metapneumovirus, with late autumn and winter peaks in picornavirus (including rhinovirus).19 Second, the antibiotics most commonly co-dispensed with one-off ICS — amoxicillin and roxithromycin — are commonly prescribed for respiratory infections.21 Third, 70% of co-dispensed ICS and oral antibiotics were dispensed on the same day, supporting the hypothesis that they were dispensed for treatment of the same clinical event. In 22.5% of cases the antibiotics were dispensed up to a week before the ICS, suggesting that these ICS were dispensed for respiratory symptoms that had failed to respond to antibiotics; however, the prescribing date itself was not available from the PBS dataset.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This analysis was conducted on a national administrative dataset recorded electronically at the point of dispensing. The estimate of the extent of inappropriate prescribing of ICS is conservative. In order to ensure close to complete dispensing data for each individual, the study cohort was limited to concession card holders since many respiratory medications and oral antibiotics were only captured in the Australian PBS dataset for persons receiving medications at the concessional rate. This excluded around one-third of people dispensed respiratory medications in 2008. Furthermore, the study population was limited to those with only one ICS prescription in 12 months and no other respiratory medicines. People who were co-dispensed ICS and antibiotics on more than one occasion in a year would not therefore be included in the present analysis. Lastly, we used ±7 days as the cut-off to define co-prescription of one-off ICS and oral antibiotics; this is substantially shorter than the typical duration of lower respiratory tract infections (median 18 days, mean 24 days)22 so, if anything, the extent of co-prescribing of one-off ICS with antibiotics for a single clinical event would have been underestimated. Hence, the cost to the Australian government for the inappropriate use of ICS as treatment of respiratory tract infections is likely to be far greater than $2.7million per year. No comment can be made about the appropriateness of the antibiotic prescriptions themselves since no diagnostic information is available in the Australian PBS dataset. However, other studies have shown that antibiotics are over-prescribed for upper respiratory tract infections in general populations in primary care.23

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Single dispensing of ICS prescribed for regular use in asthma and COPD, as a manifestation of poor adherence by patients, is well recognised,24,25 and antibiotics are commonly used in the management of exacerbations of both COPD26 and asthma27 despite the lack of evidence to support the latter. However, we are not aware of any other reports of co-prescribing of ICS and antibiotics in patients without evidence of chronic respiratory disease.

Short-term treatment of respiratory tract infections with ICS and antibiotics in patients with no other evidence of chronic airways disease is neither supported by evidence nor recommended in guidelines. A short period of treatment with ICS is rarely indicated, except as a therapeutic trial in a patient with a history and lung function consistent with mild asthma. However, such patients would be expected also to have used a short-acting β2-agonist, and the appropriate trial would be with low-dose ICS rather than moderate or high-dose ICS/LABA plus an antibiotic. For patients with chronic cough (>8 weeks in adults), guidelines recommend an empirical trial of a short course of ICS (without LABA) if eosinophilic bronchitis is considered, or extended treatment with antibiotics if the patient has persistent purulent bronchitis.16 However, again, prescribing of ICS, LABA, and antibiotics at the same time makes it unlikely that either of these was the presumed diagnosis.

Co-prescribing of ICS and antibiotics may instead reflect a lack of certainty by general practitioners about diagnosing respiratory conditions,28 or a perception that a combined anti-bacterial/anti-inflammatory approach would obviate the need for diagnostic investigations by simultaneously addressing several common potential causes of respiratory symptoms such as post-viral cough. The prominent peak in co-dispensing in the winter months may reflect the seasonality of bacterial illness (e.g. community-acquired pneumonia). Clinicians may be less likely to trust a sore throat or productive cough to resolve on its own during winter. Alternatively, they may be too busy during the winter months to risk the patient requiring a return visit (e.g. for management of post-viral cough). With regard to general practitioner decision-making, it is very interesting to note the absence of a summer (February) peak in co-dispensing of oral antibiotics and ICS in children, in contrast with the well-recognised rise in hospital admissions for asthma in children after return to school from summer holidays, which is also seen in Canada, England, Sweden, and Scotland.29,30 This back-to-school epidemic is thought to be related to children being exposed to multiple new rhinoviruses (including in the absence of clinical colds), coinciding with time-dependent factors such as allergen exposure, traffic pollution and stress, on a background of poor adherence with preventer medications during the vacation.31–33 The fact that we found no increase in co-dispensing of one-off ICS and antibiotics in children in February suggests that the clinical features leading to this pattern of prescribing differ from those seen in back-to-school asthma exacerbations.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

The finding that 50% of the patients who were dispensed only one month's supply of ICS in 2008 had no other respiratory medications dispensed — not even short-acting β2-agonists — within a 12-month period suggests that these patients were unlikely to have chronic airways disease. Co-dispensing of ICS and antibiotic may instead flag clinical episodes of respiratory tract infection.

Upper and lower respiratory tract infections are the third and tenth most commonly managed problems, respectively, in Australian primary care, together accounting for 8.7 of every 100 general practitioner consultations,21 and acute upper respiratory tract infections represent the most frequently managed problem for children in general practice.34

The use of ICS for the treatment of respiratory infections — particularly at high or moderate doses and in combination with LABA and an antibiotic — increases the risk of adverse events and adds substantially to the cost of managing what are common and usually self-limiting conditions. Prescribing of ICS for purposes beyond which they are intended comes at a cost to the Australian government which amounts to around $8million over three years and an increased risk to patients of adverse events. Our results indicate that interventions may be required to improve the quality use of ICS by targeting potentially inappropriate prescribing of short-course ICS.

The large number of patients co-dispensed ICS and antibiotics and the broad spread across geographical and socio-economic areas indicates that this prescribing pattern is not isolated to a small number of clinicians. While this study was conducted using Australian dispensing data, it will be interesting to compare the present findings with prescribing patterns for ICS in other health systems.

Further research is needed to understand the clinical rationale behind this prescribing pattern in order to plan interventions that are targeted to meet the clinical need. For example, in patients with no history of chronic respiratory symptoms, is this combination being used primarily for people with acute bronchitis or prolonged post-viral cough and/or with particular symptoms/signs? Armed with this information, a range of interventions could be designed to assist in changing prescribing behaviour — for example, decision aids for differential diagnosis of acute versus chronic respiratory symptoms;35 biomarker-based protocols to reduce the use of antibiotics;36 or prompts for general practitioners and patients about non-pharmacological strategies for respiratory infections such as those currently directed at reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.37

Conclusions

Around half of the people who receive one-off prescriptions for ICS-containing medications in Australia do not appear to have chronic airways disease and often appear to be inappropriately prescribed this medication for the management of symptoms of respiratory infections, with associated risks to patients and costs to the community. While considerable attention has already been paid to reducing inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections, our findings demonstrate that there is also a need for interventions to improve the quality of prescribing of ICS, including in the context of clinical respiratory infections. It is not known whether the pattern of prescribing reported here also occurs in other countries.

References

Adams NP, Bestall JB, Malouf R, Lasserson TJ, Jones PW . Beclomethasone versus placebo for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2).

Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, Baltzan M, Cai B . Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med 2000;343(5):332–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200008033430504

Sin DD, Man J, Sharpe H, Gan WQ, Man SF . Pharmacological management to reduce exacerbations in adults with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;292(3):367–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.3.367

Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EHA, Fong KM . Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(7):CD002991.

Yang IA, Fong K, Sim EHA, Black PN, Lasserson TJ . Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(4).

National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma management handbook. Melbourne: National Asthma Council Australia, 2006.

McKenzie DK, Abramson M, Crockett AJ, et al. The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2011. Lutwyche, Queensland: Australian Lung Foundation, 2011.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2011.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2011.

NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Prescriptions dispensed in the community: England. Statistics for 2000 to 2010. 2011.

Department of Health and Ageing. About the PBS. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2012.

Department of Health and Ageing. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Expenditure and prescriptions twelve months to 30 June 2011. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2012.

Australian Centre for Asthma Monitoring. Asthma in Australia 2011. AIHW Asthma Series no. 4. Cat. no. ACM 22. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011.

Calverley PMA, Stockley RA, Seemungal TAR, et al. Reported pneumonia in patients with COPD: findings from the INSPIRE study. Chest 2011;139(3):505–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-2992

Crim C, Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, et al. Pneumonia risk in COPD patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids alone or in combination: TORCH study results. Eur Respir J 2009;34(3):641–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00193908

Gibson PG, Chang AB, Glasgow NJ, et al. CICADA: Cough in Children and Adults: Diagnosis and Assessment. Australian cough guidelines summary statement. Med J Aust 2010;192(5):265–71.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-economic indices for areas (technical paper). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC). ABS Cat. no. 1216.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010.

Druce J, Tran T, Kelly H, et al. Laboratory diagnosis and surveillance of human respiratory viruses by PCR in Victoria, Australia, 2002–2003. J Med Virol 2005;75(1):122–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.20246

Johnston NW . The similarities and differences of epidemic cycles of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma exacerbations. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2007;4(8):591–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.200706-064TH

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2010. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010.

Ward JI, Cherry JD, Chang S-J, et al. Efficacy of an acellular pertussis vaccine among adolescents and adults. N Engl J Med 2005;353(15):1555–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa050824

Spiritus E . Antibiotic usage for respiratory tract infections in an era of rising resistance and increased cost pressure. Am J Manag Care 2000;6(23 Suppl):S1216–21.

Williams LK, Joseph CL, Peterson EL, et al. Patients with asthma who do not fill their inhaled corticosteroids: a study of primary nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120(5):1153–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.020

Penning-van Beest F, van Herk-Sukel M, Gale R, Lammers J-W, Herings R . Three-year dispensing patterns with long-acting inhaled drugs in COPD: a database analysis. Respir Med 2011;105(2):259–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2010.07.007

Daniels JMA, Snijders D, de Graaff CS, Vlaspolder F, Jansen HM, Boersma WG . Antibiotics in addition to systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181(2):150–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200906-0837OC

Glauber JH, Fuhlbrigge AL, Finkelstein JA, Homer CJ, Weiss ST . Relationship between asthma medication and antibiotic use. Chest 2001;120(5):1485–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.120.5.1485

Dennis SM, Zwar NA, Marks GB . Diagnosing asthma in adults in primary care: a qualitative study of Australian GPs' experiences. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19(1):52–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2009.00046

Johnston NW, Sears MR . Asthma exacerbations. 1: Epidemiology. Thorax 2006;61(8):722–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2005.045161

Sears MR, Johnston NW . Understanding the September asthma epidemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120(3):526–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.047

Lister S, Sheppeard V, Morgan G, Corbett S, Kaldor J, Henry R . February asthma outbreaks in NSW: a case control study. Aust NZ J Public Health 2001;25(6):514–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00315.x

Johnston NW, Johnston SL, Duncan JM, et al. The September epidemic of asthma exacerbations in children: a search for etiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115(1):132–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.025

Tovey ER, Rawlinson WD . A modern miasma hypothesis and back-to-school asthma exacerbations. Med Hypotheses 2011;76(1):113–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2010.08.045

Charles J, Pan Y, Britt H . Trends in childhood illness and treatment in Australian general practice, 1971–2001. Med J Aust 2004;180:216–19.

Levy ML, Fletcher M, Price DB, Hausen T, Halbert RJ, Yawn BP . International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) guidelines: diagnosis of respiratory diseases in primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2006;15(1):20–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.10.004

Burkhardt O, Ewig S, Haagen U, et al. Procalcitonin guidance and reduction of antibiotic use in acute respiratory tract infection. Eur Respir J 2010;36(3):601–07. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00163309

National Prescribing Service. Respiratory tract infections: symptomatic management pad and patient counselling tool. Sydney: National Prescribing Service, 2012.

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Mike Thomas

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

Sections of this paper are based on data made available by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The authors are responsible for the use made of the data in this paper. The assistance of Elyse Guevara-Rattray in preparing the manuscript is appreciated.

Funding Woolcock Institute of Medical Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HKR and GBM conceived the study. RDA performed the statistical analysis. LMP drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

HKR has participated on advisory committees for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis; is participating on a joint data monitoring committee for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Novartis; has provided consultancy services for GlaxoSmithKline; has spoken about asthma and COPD guidelines at symposia funded by AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline. GBM has served on advisory boards for Novartis; has given lectures at symposia funded by Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca; and has received research funding from AstraZeneca.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Poulos, L., Ampon, R., Marks, G. et al. Inappropriate prescribing of inhaled corticosteroids: are they being prescribed for respiratory tract infections? A retrospective cohort study. Prim Care Respir J 22, 201–208 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00036

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00036

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence of asthma—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap in patients with airflow limitation

The Egyptian Journal of Bronchology (2021)

-

Use of antibiotics and asthma medication for acute lower respiratory tract infections in people with and without asthma: retrospective cohort study

Respiratory Research (2020)

-

Prevalence of inappropriate prescribing of inhaled corticosteroids for respiratory tract infections in the Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2014)