Abstract

Background:

Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against RANK ligand, increased bone mineral density (BMD) and reduced fracture risk vs placebo in a phase 3 trial in men with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). The present analysis of this study evaluated BMD changes after 36 months in responder subgroups and in individual patients for three key skeletal sites (lumbar spine (LS), femoral neck (FN) and total hip (TH)) and the distal radius.

Methods:

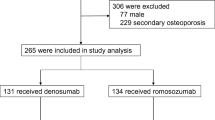

Men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer receiving ADT were treated with subcutaneous denosumab 60 mg (n=734) or placebo (n=734) every 6 months for up to 36 months in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. Patients were instructed to take supplemental calcium and vitamin D. For this BMD responder analysis, the primary outcome measure was the percentage change in BMD from baseline to month 36 at the LS, FN and TH as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. BMD at the distal 1/3 radius at 36 months was measured in a substudy of 309 patients.

Results:

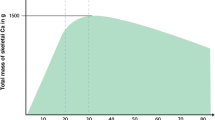

At 36 months, significantly more patients in the denosumab arm had increases of >3% BMD from baseline at each site studied compared with placebo (LS, 78 vs 17%; FN, 48 vs 13%; TH, 48 vs 6%; distal 1/3 radius, 40 vs 7% (P<0.0001 for all)). BMD loss at the LS, FN and TH occurred in 1% of denosumab-treated patients vs 42% of placebo patients, and BMD gain at all three sites occurred in 69% of denosumab patients vs 8% of placebo patients. Lower baseline BMD was associated with higher-magnitude BMD responses to denosumab at the LS, FN and TH.

Conclusions:

In men with prostate cancer receiving ADT, significantly higher BMD response rates were observed with denosumab vs placebo. Patients with lower baseline T-scores benefited the most from denosumab treatment.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $64.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E . Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46: 765–781.

Brawley OW . Prostate carcinoma incidence and patient mortality: the effects of screening and early detection. Cancer 1997; 80: 1857–1863.

La Vecchia C, Bosetti C, Lucchini F, Bertuccio P, Negri E, Boyle P et al. Cancer mortality in Europe, 2000–2004, and an overview of trends since 1975. Ann Oncol 2009; 21: 1323–1360.

Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, Mason M, Matveev V et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2011; 59: 572–583.

Barry MJ, Delorenzo MA, Walker-Corkery ES, Lucas FL, Wennberg DC . The rising prevalence of androgen deprivation among older American men since the advent of prostate-specific antigen testing: a population-based cohort study. BJU Int 2006; 98: 973–978.

Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS . Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 154–164.

Smith MR, McGovern FJ, Zietman AL, Fallon MA, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA et al. Pamidronate to prevent bone loss during androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 948–955.

Morote J, Orsola A, Abascal JM, Planas J, Trilla E, Raventos CX et al. Bone mineral density changes in patients with prostate cancer during the first 2 years of androgen suppression. J Urol 2006; 175: 1679–1683; discussion 1683.

Maillefert JF, Sibilia J, Michel F, Saussine C, Javier RM, Tavernier C . Bone mineral density in men treated with synthetic gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for prostatic carcinoma. J Urol 1999; 161: 1219–1222.

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 1998; 93: 165–176.

Amgen Prolia®. (Denosumab) Package Insert. Amgen: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011.

Smith MR, Egerdie B, Hernandez Toriz N, Feldman R, Tammela TL, Saad F et al. Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 745–755.

Smith MR, Saad F, Egerdie B, Szwedowski M, Tammela TL, Ke C et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol 2009; 182: 2670–2675.

Riggs BL, Melton III LJ, Robb RA, Camp JJ, Atkinson EJ, McDaniel L et al. A population-based assessment of rates of bone loss at multiple skeletal sites: evidence for substantial trabecular bone loss in young adult women and men. J Bone Miner Res 2008; 23: 205–214.

Bonnick SL, Johnston Jr CC, Kleerekoper M, Lindsay R, Miller P, Sherwood L et al. Importance of precision in bone density measurements. J Clin Densitom 2001; 4: 105–110.

Tanvetyanon T . Physician practices of bone density testing and drug prescribing to prevent or treat osteoporosis during androgen deprivation therapy. Cancer 2005; 103: 237–241.

Greenspan SL, Nelson JB, Trump DL, Resnick NM . Effect of once-weekly oral alendronate on bone loss in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 416–424.

Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, Kendler DL, Wang H, Liu Y et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 2149–2157.

Ellis GK, Bone HG, Chlebowski R, Paul D, Spadafora S, Smith J et al. Randomized trial of denosumab in patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for non-metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4875–4882.

Sebba AI . Significance of a decline in bone mineral density while receiving oral bisphosphonate treatment. [erratum appears in Clin Ther June 2008;30(6):1177–1178]. Clin Ther 2008; 30: 443–452.

Seeman E . Pathogenesis of bone fragility in women and men. Lancet 2002; 359: 1841–1850.

Smith MR, Boyce SP, Moyneur E, Duh MS, Raut MK, Brandman J . Risk of clinical fractures after gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol 2006; 175: 136–139.

Guise TA . Bone loss and fracture risk associated with cancer therapy. Oncologist 2006; 11: 1121–1131.

Cummings SR, Cawthon PM, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Fink HA, Orwoll ES . BMD and risk of hip and nonvertebral fractures in older men: a prospective study and comparison with older women. J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21: 1550–1556.

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H . Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 1996; 312: 1254–1259.

Acknowledgements

We thank Geoffrey Smith, PhD, of Amgen, and Linda Melvin, BA, for providing medical writing assistance on behalf of Amgen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The research was funded by Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA. Dr RB Egerdie has received consulting fees and honoraria from Amgen, Bayer and Pfizer. Dr F Saad has received grant support from Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis and Amgen, and consulting fees and honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis and Amgen. Dr MR Smith has received consulting fees from Amgen, GTx and Novartis, and honoraria from Amgen and GTx. Dr TLJ Tammela has received consulting fees from Orion Pharma and AstraZeneca, and honoraria from AstraZeneca and Astellas. Dr J Heracek has received consulting fees from Amgen. Dr P Sieber has received consulting fees from Amgen and GTx. Drs C Ke, R Dansey and C Goessl are Amgen employees and own Amgen stock. Dr B Leder has received consulting fees from Amgen and New England Research Institutes, and honoraria from Merck and Novartis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Egerdie, R., Saad, F., Smith, M. et al. Responder analysis of the effects of denosumab on bone mineral density in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 15, 308–312 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2012.18

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2012.18

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Twice-weekly teriparatide improves lumbar spine BMD independent of pre-treatment BMD and bone turnover marker levels

Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism (2021)