Abstract

Schizophrenia is a disorder in which disturbances in the integration of emotion with cognition plays a central role and probably involves several different regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, the hippocampal formation, and basolateral amygdala (BLA). Recent brain imaging studies have reported changes in volume, whereas postmortem studies point to dysfunction of the GABA and glutamate systems in these regions. Microarray-based profiles indicate that complex changes in the expression of genes associated with synaptic transmission and ion channels are involved in GABA cell dysfunction in schizophrenics. Molecular abnormalities vary considerably on the basis of sector and layer, suggesting that the unique connectivity of intrinsic and extrinsic afferents may critical in regulating the activity of genes in specific subpopulations of GABA cells. Projections of the BLA may be of particular importance to the induction of abnormal circuitry in schizophrenia, as their ingrowth during late adolescence and early adulthood may help to ‘trigger’ the onset of illness in susceptible individuals. A preponderance of cellular and molecular abnormalities has been found in the stratum oriens (SO) of sectors CA3/2 in which BLA afferents provide a robust innervation. These observations have lead to the development of a rodent model for the study of abnormal circuitry in this disorder. For example, single-cell recordings in hippocampal slices exposed to increased activation from the BLA have shown decreases in GABA currents in pyramidal neurons in SO of CA3/2, but not CA1, and support the validity of this model. Overall, the postmortem studies of neural circuitry abnormalities in schizophrenia are beginning to implicate specific cellular, molecular, and electrophysiological mechanism in specific subtypes of cortical neurons defined by their afferent and efferent connectivity within key corticolimbic regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Recent advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia have brought into play an expanded understanding of how neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms within key corticolimbic regions contribute to the functional integrity of the brain. The discussion below begins with a description of some core features of this disorder and discusses how various components of the limbic lobe and other neocortical areas can be implicated in its pathophysiology (Figure 1). Although recent brain imaging studies have suggested that abnormalities in limbic lobe components may contribute to a dysfunctional regulation of affective responses in schizophrenics, postmortem investigations, particularly those in the anterior cingulate region and hippocampus, have provided compelling evidence for a defect of GABAergic function in schizophrenia. Many recent studies have uncovered a preponderance of abnormalities in certain layers and/or sectors of these brain areas. Both brain imaging and postmortem studies have suggested a central role of the basolateral amygdala (BLA) in the pathophysiology of this disorder. The recent application of microarray-based gene expression profiling (GEP), together with laser microdissection (LMD), has made it possible to ‘deconstruct’ specific circuits, such as the trisynaptic pathway, and has shown that the regulation of these circuits and their activity are far more complex than was heretofore suspected. The regulation of synaptic transmission in specific subtypes of neurons within the circuitry of the hippocampus is dependent on many different factors and a full understanding of their function in normal and abnormal states will require a very detailed analysis of their inputs and how they interact with specific cellular and molecular mechanisms that drive their function. Finally, the discussion below will address the question of why schizophrenia typically presents between 16 and 25 years of age and will explore whether there are postnatal developmental changes within limbic lobe circuitry that could play a potential role in ‘triggering’ the onset of this disorder in susceptible individuals.

The corticolimbic system consists of several brain regions that include the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampal formation, and basolateral amygdala. The anterior cingulate cortex has a central role in processing emotional experiences at the conscious level and selective attentional responses. Emotionally related learning is mediated through the interactions of the basolateral amygdala and hippocampal formation and motivational responses are processed through the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

AFFECTIVE REGULATION

The symptoms of schizophrenia are notably very complex and involve disturbances in a wide variety of behavioral categories, including emotion, motivation, selective attentional responses, and social interactions (Figure 1). More than half a century ago, studies showed that surgical ablations of certain corticolimbic regions result in changes in the ‘temperament’ of both monkeys (Ward, 1948a, 1948b) and humans (Tow and Whitty, 1953). In this section, several features of personality, known to be abnormal in schizophrenia, will be considered in relation to the limbic lobe (Broca, 1878). This region includes the anterior cingulate cortex (ACCx), hippocampal formation (HIPP), and BLA.

Basolateral Amygdala

The BLA is part of a frontotemporal system that innervates several key components of the corticolimbic system, including, as discussed below, the ACCx and hippocampal formation (Swanson and Petrovich, 1998a). The amygdala mediates behaviors, such as aggression and sexual activity (Davis, 1992), which in turn influences social behavior. For example, cats with abnormally increased neuronal activity within the BLA show a reduced ability to interact socially and tend to hide when introduced to novel stimuli (Adamec, 1978, 1991). On the other hand, animals with extensive amygdala ablations seem to lose fear response completely (Kluver and Bucy, 1937; Aggleton, 1993). Interestingly, these changes are very similar to those seen in schizophrenia. In humans, lesions of the amygdala have been associated with a decrease or even absence of conditioned fear responses to aversive stimuli, and it is believed that such patients are unable to attach affective coloration to emotionally charged stimuli (Bechara et al, 1999).

The amygdala also plays a central role in modulating memory and learning associated with stress and emotion (Kim and Diamond, 2002). The cingulate cortex works cooperatively with the BLA in mediating certain types of conditioned memory. For example, rabbits with lesions of the amygdala show a decrease of discriminative avoidance learning (medial prefrontal cortex, mPFCx) (Poremba and Gabriel, 1997). Although the amygdala is probably not the actual site for long-term storage of explicit or declarative memory, it seems to influence memory-storage mechanisms in other brain regions that notably include the hippocampal formation (Cahill et al, 1996). Selective bilateral damage to the amygdala is associated with an inability to acquire conditioned autonomic responses to visual or auditory stimuli (Bechara et al, 1995).

The BLA also plays a complex role in associative learning and attention (Gallagher and Holland, 1994). For example, this region regulates sensorimotor gating of the acoustic startle response (Wan and Swerdlow, 1997) and contributes to fear conditioning (Stutzmann and LeDoux, 1999). The latter behavior seems to involve modulation by GABAergic interneurons. Some authors believe the BLA contributes to the plasticity associated with the encoding of fear conditioning (Fanselow and LeDoux, 1999) and goal-directed behaviors (Schoenbaum et al, 1998). Rats with lesions of the BLA are insensitive to postconditioning changes in the value of a reinforcer (Hatfield et al, 1996). Interestingly, blockade of the GABAA receptor results in a marked change in the regulation of emotional responses mediated by this region (Davis, 1994; Sanders and Shekhar, 1995).

Anterior Cingulate Cortex

As described by Bleuler in 1952, a hallmark feature of schizophrenia is a progressive flattening of affect that results in facial expressions that lack emotion (Bleuler, 1952). Generally speaking, schizophrenics are unable to tolerate a high degree of emotion expressed by others around them, particularly family members (Barrelet et al, 1990). A variety of studies have shown that the ACCx has a central role in processing emotion at the cortical level (for a review, see Benes et al, 2009) and involves the larger limbic lobe network. Patients with lesions affecting the cingulate cortex or those with therapeutic cingulotomies show a decreased ability to experience and express affect (Damasio and Van Hoesen, 1983). The ‘gut level’ experience of emotion requires direct descending and ascending interconnections of ACCx with autonomic nuclei at brainstem and spinal cord levels that modulate the activity of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems (for a review, see Neafsey et al, 1993). In turn, visceral afferents from peripheral autonomic end organs, including the heart, blood vessels, gastrointestinal tract and bladder, carry sensory information back to the nucleus solitarius at medullary levels and these eventually influence the principal components of the limbic lobe that include the ACCx, amygdala, and hippocampal formation (see Benes et al. 2009).

An important aspect of the behavioral responses associated with the BLA is its connectivity with the ACCx (mPFCx in rodents). This is not surprising, because there is extensive connectivity between these two regions (Van Hoesen et al, 1993). For example, the BLA provides a bilaminar innervation to layers II and V of ACCx. The BLA projection to layer II of this region in primates is ‘massive’, (Van Hoesen et al, 1993), and this fact could potentially help to explain the preferential occurrence of abnormalities in this layer in postmortem studies of schizophrenia (Table 1). It seems plausible that affective responses may be driven, at least in part, by discharges of activity originating in the BLA and terminating in the ACCx.

As shown in Figure 2, the density of amygdalar fibers projecting to ACCx during the equivalent of adolescence and early adulthood in rat brain (Verwer et al, 1996) (Cunningham et al, 2002) and the number of synaptic contacts formed continue to increase significantly (Cunningham et al, 2002). Most of these appositions form asymmetric synapses with dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons. As shown in Figure 3, many of these appositions are also found on the dendrites of GABAergic cells that lack spinous processes (Cunningham et al, 2008). This latter pattern is consistent with the observation that stimulation of the BLA results in a preponderance of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials within the mPFC (Perez-Jaranay and Vives, 1991). Taken together, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the ingrowth of BLA fibers into ACCx during adolescence could contribute to the development of emotional maturity in normal individuals, whereas those who are ‘at risk’ for schizophrenia may become ill. The fact that individuals with schizophrenia do not display or experience affect implies that the information flowing from the peripheral autonomic systems is either not reaching the ACCx or is not being appropriately integrated with BLA afferent activity.

Postnatal increases in projections from the basolateral amygdala (BLA) to the anterior cingulate cortex (ACCx). (a, b) BLA fibers visualized with an anterograde tracer show a bilaminar distribution in layers II and V of ACCx. During the preweanling period, the BLA fibers at postnatal day 6 (P6) and P16 are sparsely distributed in both layers. During the postweanling period (P26–P45), the BLA fiber density shows dramatic increases and eventually reach a maximum during the early adult period. (c) At the electron microscopic level, anterogradely traced BLA fibers course through the neuropil and form synaptic connections with dendritic spines (red asterisk). These profiles show classic postsynaptic densities associated with excitatory synapses. (d) These axospinous synapses, presumed to be with pyramidal neurons, show a highly significant increase between the early preweanling and early adult periods (P15 and 60, respectively). See Cunningham et al (2002) for more detail.

A co-localization study shows the interaction of fibers from the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and GABAergic interneurons in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACCx). Many BLA fibers (red) can be seen in the neuropil and in apposition with the cell body of a GABAergic interneuron and the shafts of its dendrites (green). Unlike pyramidal neurons, the dendrites of GABA cells typically do not show spinous processes. At the electron microscopic level, the BLA fibers are filled with vesicles similar to those seen at classic synapses; however, the BLA terminations do not show the usual membrane specializations associated with synaptic contacts, suggesting that they exert a slower, modulatory influence on interneurons. See Cunningham et al (2008) for more details.

The Hippocampal Circuit

The hippocampus plays a pivotal role in learning and memory; however, its memory-storage mechanisms probably involve an interplay with the BLA (Cahill and McGaugh, 1996), one that involves the stress response (Roozendaal, 2000). Specifically, the BLA is necessary for the expression of the modulatory effects of stress on hippocampal LTP and memory consolidation (Kim et al, 2001). Additionally, the hippocampus also mediates associative learning that is contextual in nature (Selden et al, 1991). It is noteworthy that episodic memory retrieval is abnormal in schizophrenia and this defect has been specifically related to information processing within the hippocampal formation (Heckers et al, 1998).

The basic cytoarchitectural layout of the mammalian hippocampus is quite similar across all mammalian species, making it a useful system for testing specific hypotheses derived from postmortem studies in human brain (see the discussion below). The trisynaptic pathway (Figure 4) of the hippocampus is perhaps the most extensively characterized circuit in the central nervous system. As shown in Figure 4, it consists of three synaptic relays. The first leg of the circuit involves the mossy fibers that originate from the granule cells of the area dentata. They terminate on the distal apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons in the stratum radiatum (SR) of sector CA3 (Acsady et al, 1998a). The mossy fibers at this locus also terminate on GABAergic interneurons and contribute to feed forward inhibition along the trisynaptic path (Frotscher, 1989). These fibers probably use kainate- (Bortolotto et al, 2003) and AMPA-sensitive (Hirbec et al, 2003; Lauri et al, 2001) glutamate receptors to mediate their postsynaptic responses. Pyramidal neurons receiving mossy fiber inputs, in turn, send excitatory recurrent collaterals to GABAergic cells in the SR; these synaptic effects are mediated by AMPA receptors and NMDA-mediated LTP responses (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996b), as well as a feedback suppression of firing in the same projection cells by their target GABA cells (Crepel et al, 1997).

A schematic diagram of pyramidal cells (triangular) and GABAergic interneurons (square) within the trisynaptic pathway of the hippocampus. The functional categories of genes evaluated for changes in expression as a group are indicated on the various neuronal cell types at each locus along the trisynaptic pathway. GABA cells in which GAD67 expression is significantly decreased are indicated with a light blue fill color in the stratum radiatum and stratum oriens (SO) of sector CA3/2 and in the SO of sector CA1. Although these latter three interneuronal subpopulations may show a decreased ability to exert inhibitory modulation of the pyramidal neurons in their sector, closer scrutiny of the various functional categories of genes indicates that the overall pattern of expression changes are quite different at each locus, suggesting that the unique connectivity found at each of these sites may have an important function in determining how neurotransmitter receptors, signaling pathways, metabolic pathways, and other complex groups of genes involved in transcription, translation, and DNA repair are regulated. See Benes et al (2007) for more details.

Neurons of CA3/2, particularly GABA cells in the SO of this sector, receive inputs from subcortical regions, such as the hypothalamus, septal nuclei, and BLA (Rosene and Van Hoesen, 1987). The innervation provided by the latter region is rather complex and also includes the perforant pathway terminations in the stratum moleculare of the area dentata, as well as various other fibers systems that enter the CA subfields, either through the stratum oriens (SO) of CA3/2 or the stratum moleculare of CA1 (Pikkarainen et al, 1999). Cholinergic (Dringenberg and Vanderwolf, 1996) and GABAegic (Toth et al, 1997) inputs to GABA cells in SO of CA3/2 originate in the basal forebrain, whereas glutamatergic projections (Swanson and Petrovich, 1998b) to both pyramidal neurons and GABA cells originate in the BLA (Cunningham et al, 2007) and, to a lesser extent, the septal nuclei (Sotty et al, 2003). Experimental stimulation of projection neurons in the BLa is associated with a reduction in the number of GABA cells in the SO of sector CA3/2 (Berretta et al, 2001), a pattern remarkably similar to that seen in postmortem studies of SZ (see discussion below).

Pyramidal cells in CA3 and CA2 send Schaffer collaterals to the SR of CA1 where they provide an excitatory input to the apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons in this sector. These projection cells are modulated by a variety of GABAergic interneurons located in the SR, stratum pyramidale (SP), and SO of this sector. The GABA cells in CA1 sector are also part of a GABAergic network that includes interneurons in sectors CA3/2 (Buzsaki, 1997). Pyramidal cells in CA1 ultimately send their excitatory fibers to a variety of sites, including the subiculum, BLA, and prefrontal cortex. (for a review, see Rosene and Van Hoesen, 1987).

LIMBIC LOBE FINDINGS IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

On the basis of the above discussion, the ACCx, hippocampus, and amygdala may be of central importance to understanding the emotional disturbances that are commonly encountered in patients with schizophrenia (Benes, 1993). In the discussion that follows, recent findings from brain imaging and postmortem studies of schizophrenia are presented with a view toward establishing more specifically the ways in which these regions may be altered in this disorder.

Brain Imaging Studies of Schizophrenia

Hippocampal and amygdalar volume and activity

A recent meta-analysis of the size of various brain structures in first episode schizophrenics has concluded that the left and right hippocampus, but not the amygdala, showed a significant reduction in volume across six separate studies in which magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used (Vita et al, 2006). In one original report, the volumes of the hippocampus and amygdala were both observed in subjects with chronic schizophrenia, though first episode schizophrenics only showed volume loss in the left hippocampus (Velakoulis et al, 2006). These findings suggest that pathophysiological changes in the hippocampus of schizophrenics may be primary in nature, whereas those in the amygdala may be secondarily related to the disease process. In a review of imaging studies in children and adolescents with schizophrenia, a decreased volume of both of these regions, as well as the ACCx, has been reported (White et al, 2007). This latter study emphasizes the neurodevelopmental nature of schizophrenia and raises important questions regarding the time course for the appearance of brain imaging abnormalities in key limbic lobe structures.

Schizophrenia typically enters the prodrome of illness during late adolescence and early adulthood. This observation has suggested the possibility that late postnatal maturational changes in the brain may have a role in ‘triggering’ the onset of this disorder in individuals who carry the appropriate susceptibility genes (Benes, 1989).

The amygdala and fearful responses to faces

As noted above, the amygdala has a central role in detecting and responding to fear-provoked stimuli (Phelps and LeDoux, 2005). Using tasks of emotion recognition, emotional expression, and emotional experience, a functional (fMRI) study has shown an attenuated response of the amygdala to emotional stimuli as compared with neutral stimuli (Aleman and Kahn, 2005). Indeed, schizophrenics may actually show a heightened activation of the amygdala in response to neutral faces (Hall et al, 2008). When the ability of schizophrenics to recognize and retrieve happy, sad, and neutral faces was assessed, the patients showed an overall lower memory performance than controls. Controls activated a much larger set of regions for happy faces, including areas thought to underlie recollection-based memory retrieval, such as the hippocampus. These findings suggest that emotional memory in response to novel stimuli may be intact in schizophrenia, despite the emotion-specific differences in the brain regions that are activated (Sergerie et al, 2009). On the other hand, diminished amygdala reactivity in schizophrenia patients in response to negative facial stimuli has been found to be coincident with an alteration in the functional coupling between the amygdala and subgenual cingulate cortex, a subdivision of an anterior portion of the cingulate gyrus (Rasetti et al, 2009). Interestingly, unaffected siblings show a pattern that is similar to that of healthy controls, suggesting that the inability to engage the amygdala, cingulate cortex, and hippocampus in processing stimuli with high emotional valence may be related to effects of the disease state on the limbic lobe network.

Postmortem Studies of the Limbic Lobe

GABA system

Evidence for disturbances of the GABA system in the hippocampus of schizophrenics has also been observed. For example, studies have shown a reduction in high affinity GABA uptake (Reynolds et al, 1990) and increased GABAA receptor-binding activity (Benes et al, 1996a) in this region of schizophrenics. As shown in Table 2, the latter findings for the GABAA receptor were most strikingly present in sectors CA4, CA3, and CA2, whereas CA1 showed only a small difference (Table 2). Many markers, however, showed a predominance of abnormalities in sectors CA3/2, but not CA1. In both the anterior cingulate (Benes et al, 1992b) and prefrontal (Benes et al, 1996b) cortices, the increase in this receptor activity was selectively present on pyramidal neurons in layers II and III (Table 1), reflecting a potential compensatory upregulation of this receptor in response to a decrease in GABAergic inhibition of projection neurons. There was no change in the number of GABAergic terminals in these two regions of schizophrenics; however, increases in terminal size were observed in schizophrenics receiving neuroleptic drugs at the time of death. A similar analysis of terminals containing the 65 kDa isoform of glutamate decarboxylase [GAD65] in the hippocampus also showed no overall differences in the density of GABAergic terminals in neuroleptic-free schizophrenics (Todtenkopf and Benes, 1998). Most notably, however, those patients treated with these drugs showed a dose-related increase in GAD65 terminals that was most striking in the SO of sectors CA3 and CA2, particularly in the SO of these sectors. It is possible that antipsychotic medications may be capable of acting, at least in part, by inducing a sprouting of GABAergic terminals in the hippocampus of schizophrenic brain. This conclusion is consistent with findings in mPFCx of rats treated chronically with haloperidol where axosomatic contacts with pyramidal neuron cell bodies showed this effect (Vincent et al, 1994). Thus, neuroleptic drugs may be capable of inducing a sprouting of GABAergic terminals that could help to compensate for a decrease in the activity of this system.

In the amygdala, reductions in GABAergic activity have also been suggested by early findings of reduced GABA concentrations (Spokes et al, 1980) and decreases in high affinity GABA uptake sites (Simpson et al, 1989; Reynolds et al, 1990). Unfortunately, there have been no other studies of the GABA system in this region of schizophrenics. However, the hypothesis that the amygdala may have a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia has been suggested by other indirect information. For example, the amygdala sends a massive projection to layer II of the ACCx in which microscopic anomalies have been preferentially observed in schizophrenia (Benes and Bird, 1987; Benes et al, 1987, 1991, 1992a, 1997a, 1992b, 1996b, 2001b; Todtenkopf et al, 2005; Woo et al, 2008; Woo et al, 2007, 2004). For a summary of these studies, see Table 1. It is also relevant to note that the same subdivision of this region also sends a dense projection to sectors CA2/3 in the hippocampus in which postmortem abnormalities have also been observed in schizophrenia (Benes et al, 1996a, 1998, 2008, 2007a; Benes and Todtenkopf, 1999; Pantazopoulos et al, 2004; Todtenkopf and Benes, 1998; Todtenkopf et al, 2005). For a summary of these results, see Table 2.

Glutamatergic receptors

There is evidence that schizophrenia may also involve abnormalities of the glutamate system. In the hippocampal formation, a reduction in non-NMDA glutamate receptors, particularly those that are sensitive to kainate (KAR) and associated messenger RNA mRNA (mRNA) for kainate receptors have also been observed in sectors CA2, 3, and 4 of patients with this disorder (Harrison et al, 1991; Kerwin et al, 1990, 1988), whereas little change in NMDA or AMPA receptors was detected (Harrison et al, 1991). For the KAR on the other hand, the expression of mRNA for the GluR6 and 7 subunits in GABA neurons found in the SO of sectors CA3/2 was found to be significantly increased in schizophrenics (Benes et al, 2008). In pyramidal neurons, however, a significant reduction in immunoreactivity for the KAR protein (GluR5,6,7-IR) has been found on their apical dendrites and this change occurred to the greatest degree in sector CA2 (Benes et al, 2001a). Taken together, these studies suggest that the expression of the KAR may have an important function in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia; however, changes in this receptor system seem to vary by region, subregion, and even neuronal cell type. Although it is possible that the reduction in KARs is the result of a primary genetic anomaly, it is equally plausible that a reduction in kainate-sensitive glutamate binding may represent a compensatory downregulation in response to increased incoming excitatory activity. If this latter hypothesis were correct, it would be consistent with the idea that an excitotoxic mechanism mediated through the KAR could have a role in inducing the changes seen in the hippocampus of schizophrenics. This idea is appealing because some believe that GABAergic cells in the hippocampus are particularly sensitive to KAR-mediated injury (Schwarcz and Coyle, 1977; Morin et al, 1998).

In the ACCx, recent double-labeling studies have shown that the density of the GAD67 mRNA-containing neurons that co-express mRNA for the NR2A subunit of the NMDA receptor (Woo et al, 2004) and the GluR5 subunit of the KAR (Woo et al, 2007) were decreased by 80 and 43%, respectively, in layer II of the ACCx in schizophrenia. GluR6-expressing GABA cells did not show differences. These findings obtained using double-labeling techniques have suggested that changes in the regulation of glutamate receptors may occur preferentially in GABAergic interneurons (see discussion below).

Interconnections of limbic lobe regions

As a general rule, it is not possible to study connectivity of corticolimbic networks in human brain because traditional tract tracing techniques cannot be used. One approach that is currently feasible, however, is the use of immunocytochemistry to localize fiber systems within various components of this system. Although such a strategy can be relatively specific for projections that emerge from discrete nuclei and use a characteristic transmitter system (eg dopamine and serotonin), it can otherwise provide nonspecific data from which meaningful inferences can be drawn. To illustrate, using antibodies against a neurofilament 200K subunit of the axon cytoskeleton in the ACCx, an excessive number of vertical axons were found in superficial layers of schizophrenics (Benes et al, 1987). Subsequently, this finding was replicated and extended using a monoclonal antibody against a glutamate–glutaraldehyde conjugate (Benes et al, 1992a). In both studies (refer to Table 1), the finding of an increased density of vertical axons in schizophrenics was not observed in the prefrontal cortex. Initially, it was thought that the vertical fibers showing this increase in the ACCx might be associative afferents from other cortical regions because such fibers pass through layer II toward layer I where they travel horizontally for considerable distances (for a review, see Benes, 1993). As this latter region did not show an increase in vertical fibers in schizophrenics, it seemed possible that those fibers showing an increase in the anterior cingulate area might have originated in a region that projects to the latter, but not the former. Another component of the limbic lobe receiving a substantial projection from the basolateral complex is the entorhinal cortex (Amaral and Insausti, 1992). A significant increase in the density of vertical axons in the superficial layers of this region was also observed (Longson et al, 1996). Taken together with the prior results from the anterior cingulate, these postmortem findings provided compelling, albeit inferential, support for the possibility that the amygdala might send a superabundant projection to corticolimbic regions in schizophrenic brain.

CIRCUITRY-BASED CHANGES IN THE MOLECULAR REGULATION OF GABA CELLS

Regulation of GAD67 and the GABA cell Phenotype

There is now compelling evidence for a molecular defect of GABAergic neurotransmission in schizophrenia (Benes et al, 1991, 1992b). For example, patients with schizophrenia have been shown to have a decreased expression of mRNA for GAD67 in the prefrontal cortex (Akbarian et al, 1995; Guidotti et al, 2000; Volk et al, 2000), ACCx (Woo et al, 2007, 2004), and hippocampus (Benes et al, 2007). To gain some insight into the cellular and molecular mechanisms that may be involved in the regulation of this gene, laser micro dissection has been used to ‘deconstruct’ the trisynaptic pathway in the hippocampus of schizophrenics Benes et al (2007). This is a complex relay involving extrinsic and intrinsic inputs to both projection neurons and GABAergic interneurons. To explore the question of how GAD67 is regulated, the SO, SP, and SR were dissected from CA3/2 and CA1 from normal controls and schizophrenics. Microarray-based gene expression profiling (GEP) was used to identify genes that may be related to the regulation of GAD67 and to determine which might show changes in expression in GABA cells at specific points along this circuit.

Although GABA cells are found throughout the trisynaptic pathway, the SO and SR are almost exclusively populated by these neurons (Benes and Berretta, 2001). This laminar segregation has made it possible to study the regulation of GAD67 separately in the SO, SP, and SR. As shown in Table 3, GAD67 expression in the various laminae of this sector showed significant reductions in all three layers of CA3/2, although the changes in SO and SR attained much higher levels of significance. On the other hand, GABA cells in the SP showed similar fold changes; however, the P-values were much weaker and they account for only 5% of the neuronal cell volume of this layer Benes et al, (1998). Overall, GABA cells are the only neurons in the SO and SR, making these laminae strategically important loci for studying interneurons.

A new form of interrogation for GEP data, called network association analysis, was used to identify functional relationships of the GAD67 gene with other potential genes associated with synaptic transmission, signaling, metabolism, and transcriptional and translational regulation Benes et al (2007). As shown in Figure 5, this analysis has uncovered a gene cluster potentially involved in the regulation of GAD67 expression in hippocampal GABA cells (Benes et al, 2007a). The protein products of these genes are generally found in different cellular compartments (Figure 5). Genes not showing significant changes were included in the diagram because they were constitutively expressed and, as such, could interact in a functionally meaningful way with the genes showing significant changes. In addition to KAR subunits (GRIK1-5), key genes include the TGFβ signaling path (ie TGFβ2, TGFβR1, SMURF1, and SMAD3), Wnt signaling (ie LEF1, GSK-3β, and CTNNB1), cell-cycle regulation (ie CCND1), and neurogenesis (ie PAX5); several transcription factors involved in cell differentiation (ie DLX1, 2; LHX1; TLE1; Runx2; and PAX5) were also represented in the network.

A set of schematic diagrams depicting a network association analysis of genes associated with the regulation of GAD67 (GAD1) and GAD65 (GAD2) in human hippocampus. The diagram to the left shows the various genes located within the cellular compartments in which their respective proteins are located and includes the extracellular space, plasma membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus (from Ingenuity Systems). The red and blue colors indicate whether these genes show an increase or decrease, respectively, in the stratum oriens of sector CA3/2 of schizophrenics. The diagram to the right has extracted these latter genes and shows their intracellular relationship to the regulation of GAD67 and GAD65. See Bene et al (2007) for more details.

TGFβ2 is associated with the extracellular space; however, it gives rise to a critical signaling pathway that includes TGFβR1 (plasma member), SMURF1 (cytoplasm), and SMAD3 (nucleus). The TGFβ signaling pathway is associated with many different early developmental processes (Knepper et al, 2006) and disruptions of its function have been detected in several adult disease states (Attisano and Wrana, 2002). As shown in Figure 5, other genes included in the GAD67 regulatory network include CNNTB1 or β-catenin, GSK-3β, and LEF1, three key components of the Wnt signaling pathway. The latter, similar to the TGFβ pathway, also has a role in modulating early developmental events, such as the formation of the neural tube (Backman et al, 2005) and forebrain (Galceran et al, 2000). Neurogenesis during adulthood and, by inference, cell-cycle regulation have been postulated to occur in the hippocampus of schizophrenics. Thus far, in studies of SZ, this has primarily been associated with the granule cell layer in the dentate gyrus (Lipska, 2004; Reif et al, 2006; Toro and Deakin, 2006). Perhaps relevant to SZ is the fact that Wnt signaling contributes to neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus (Lie et al, 2005). Cyclin D2 is the only D-type cyclin expressed in dividing cells derived from neuronal precursors in the adult hippocampus (Kowalczyk et al, 2004). Cyclins D1, 2 (CCDN1, 2) are known to have a major role in the regulation of cell cycle, although it is important to emphasize that thus far there has been no evidence suggesting that GABA cells in the CA subfields are capable of mitotic proliferation.

As shown in Table 3, the decreased expression of the GAD67 is most prominent in CA3/2 than in CA1 (Benes et al, 2007). This provides further support for the idea that afferent inputs from the BLA to this point along the trisynaptic pathway may have a particularly important function in the regulation of GABA cell dysfunction in schizophrenia. The variability of these GEP findings suggests strongly that the unique patterns of connectivity found at different loci along the trisynaptic pathway could influence the cellular and molecular regulation of GABA cells within each locus and the oscillatory rhythms that are generated and propagated therein. It is not surprising, therefore, that abnormalities in γ oscillations have been reported in schizophrenia (Bucci et al, 2007).

As shown in Figure 4, expression changes in the hippocampus of schizophrenics are very complex. Changes in the expression of genes associated with receptor systems, signaling, metabolism, transcription, and translation, all vary according to the specific connectivity found within each layer and sector of the trisynaptic pathway (Benes et al, 2008). Accordingly, GABA cell dysfunction inferred from GEP in the SO of CA3/2 in SZs probably involves glutamatergic inputs from the BLA (Acsady et al, 1998b). Among these, subunits of the KARs showed the most impressive changes in expression at this locus and may potentially mediate at least some amygdalar effects on GABA cells in this critical layer/sector. Although the GluR5 subunit was decreased in expression, the GluR6 and 7 subunits of the KAR were significantly upregulated in the SO of CA3/2 in schizophrenics. KARs could be part of a larger mechanism that promotes neuronal excitability along GABA cell dendrites (Schaefer et al, 2007) and increases the firing rate of these cells (Lauri et al, 2005); (Lupica et al, 2001). This effect could potentially be related to an upregulation of Ih (HCN3), nonselective cationic channels (Robinson and Siegelbaum, 2003), which is associated with an attenuation of after-hyperpolarizing currents (Chen et al, 2001b; Lupica et al, 2001). This channel was also significantly increased in expression at this locus in schizophrenics and may contribute to an activation of GABA cells at this same locus. Similar changes in GEP were not associated with GABA cells in the SR of CA3/2 or in any of the layers in CA1, suggesting that the influence of specific intrinsic and extrinsic afferents (eg BLA and septal nuclei) located within the SO of CA3/2 may have a significant role in the induction of these changes in schizophrenics.

Overall, these proposed changes in the hippocampal GABA system in schizophrenia might be expected to induce an increase in excitatory activity in the trisynaptic pathway. Such a change could possibly involve changes in the influx and efflux of various ions, including sodium, potassium, and calcium that are coupled strongly to intracellular signaling cascades and amplify signals that regulate synaptic vesicle turnover in the GABAergic boutons (Holmgaard et al, 2009).

Potassium ion Channels

Several potassium ion channels, which have been postulated to have a role in the pathophysiolgy of schizophrenia (Wolfart et al, 2001; Akhondzadeh et al, 2002; Tomita et al, 2003), did show significant changes in the hippocampus of subjects with schizophrenia. Some as shown in Table 4, some of these genes encode voltage-gated channels (eg KCNAB1,2 and KCNG2) that showed significant downregulations. Most of the potassium channels showing significant changes were of the inwardly rectifying type (eg KCNJ3, KCNK2, KCNMA1, KCNV1, and KCTD12) that were upregulated (for a review, see Sadja et al, 2003). It is noteworthy that one of the other genes, SLC24A3, is responsible for regulating the dynamics of sodium, potassium, and calcium ions in neurons undergoing changes in polarization. In hippocampal GABA cells, an increase in these ions could influence the firing of GABAergic interneurons in SO of CA3/2. Finally, the nonselective hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated channel, Ih (HCN3), was also upregulated in the schizophrenic subjects. This I is channel has the highest affinity for potassium (Robinson and Siegelbaum, 2003) and believed to have a role in regulating the excitability of neurons. Additionally, the increased expression of the KAR subunits GluR6 and GluR7 also noted at this locus in schizophrenics (Benes et al, 2007b), if associated with an increase of other associated glutamate receptors, could help GABA neurons to reset their firing phase (Yang et al, 2007). Indeed, the simultaneous upregulation of KARs and the hyperpolarization-activated (Ih) cationic channel could stimulate neuronal excitability along the GABA cell dendrites (Schaefer et al, 2007) and help to increase their firing rate (Lupica et al, 2001) in patients with schizophrenia.

GABAERGIC MECHNANISMS RELATED TO HIPPOCAMPAL CIRCUITRY

Regulation of Pyramidal cell Firing by Interneurons

Pyramidal neurons send recurrent collaterals to GABAergic interneurons and stimulate them to fire through AMPA receptors. When GABA cells, in turn, are stimulated to fire, they release GABA at synapses formed on pyramidal cell bodies and dendrites and induce a hyperpolarizing potential that may prevent the latter from continuing to fire. These local circuits are present within CA3/2 and are capable of influencing the activity of analogous circuits in CA1 through Schaffer collaterals, branches of the pyramidal cell axon originating in CA3/2. The regulation of pyramidal neurons involves both excitation and inhibition; however, the relationship between these two firing patterns is frequency dependent and perhaps even unique to this region. For example, pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus seem to require high-frequency discharges to generate an excitatory response (Henze et al, 2002). Mossy fibers of granule cells in the area dentate are linked disynaptically with GABAergic interneurons and pyramidal cells in SR of CA3. When an action potential is triggered in a granule cell, it paradoxically produces a net inhibitory postsynaptic potential in pyramidal neurons in this sector, as a result of feed forward inhibition involving the interneuron (Mori et al, 2004). However, when multiple action potentials are induced in the same granule cell, the inhibitory response recorded in the pyramidal cell switches to an excitatory one. Despite the presence of two synapses in this circuit, the time needed for the initiation of an inhibitory postsynaptic potential seems to be less than that required for the excitatory response. This frequency-dependent switch is believed to be important for the modulation of synaptic strength as seen in LTP and LDP mediated in the hippocampus (Mori et al, 2004).

GABA Networks and Oscillations

Oscillatory rhythms are generated in many regions of the brain, although the hippocampus has been the prime focus of investigations into the mechanisms involved in this phenomenon. As discussed earlier (Benes and Berretta 2001), synaptic interactions between GABAergic interneurons and pyramidal cells are involved in establishing and maintaining a variety of rhythms, including those in the θ, γ (40–100 Hz), and ultrafast (200 Hz) frequency ranges (Acsady et al, 1996; Amzica and Steriade, 1995; Bragin et al, 1995a, 1995b; Burle and Bonnet, 2000; Buzsaki, 1997; Buzsaki and Eidelberg, 1983; Buzsaki et al, 1992; Fraser and MacVicar, 1991; Sik et al, 1995; Soltesz and Deschenes, 1993). These have been recorded in the neocortex (Sirota et al, 2008), hippocampus, amygdala (Pape et al, 1998), and thalamus (Pare et al, 1987). In the hippocampus, where they have been most extensively studied, basket cells exhibit highly regular membrane oscillations (Ylinen et al, 1995b). Theta-related rhythmic hyperpolarization of projection neurons is brought about by the rhythmic discharges of basket neurons, a subtype of GABA cell that specifically forms axosomatic contact with the pyramidal cell body; such connections are much more effective than those found on pyramidal cell dendrites. In the cortex, networks of inhibitory interneurons have been found to entrain pyramidal cell discharges that result in coherent oscillations (Burle and Bonnet, 2000). Similarly, in the hippocampus, large ensembles of GABAergic interneurons form networks, also called ‘supernetworks’ that provide the temporal structure that is needed to coordinate and maintain the function of neuronal ensembles. These networks are capable of generating γ-frequency oscillations (Traub et al, 1997). For the θ rhythm, intrinsic basket cells and disinhibitory GABA cells, extrinsic to the hippocampus and located in the septal nuclei, form GABA-to-GABA interactions and regulate membrane oscillations in the hippocampus (Ylinen et al, 1995c).

Gamma-frequency EEG activity is generated in the hippocampus when pools of interneurons receive a tonic or slowly varying excitation (Traub et al, 1996). The frequency of the oscillation depends on the strength of this excitation and on the parameters regulating the inhibitory coupling between the interneurons. The output of these interneuronal networks is then transmitted to pyramidal neurons in the form of rhythmically synchronized IPSPs (Traub et al, 1996). Pyramidal neurons in CA3 discharge interneurons in both CA3 and CA1 at latencies indicative of monosynaptic connections. Intrahippocampal γ oscillations emerge in the CA3 recurrent system, which then entrains the CA1 region through its interneurons (Csicsvari et al, 2003). These oscillatory rhythms are thought to be important in establishing the cognitive relevance of hippocampal output (Whittington et al, 2001); however, they are subject to potent regulatory effects of projection neurons in other brain regions. For example, the septal nuclei may be responsible for three different firing patterns of neurons in the hippocampus: slow-firing cholinergic, fast-firing, and burst-firing GABAergic and cluster-firing glutamatergic neurons (Sotty et al, 2003); each may contribute to the oscillations recorded in the hippocampus by projecting to the SO of CA3/2 in which they can interact with GABAergic interneurons. There also seems to be a temporal coordination of γ oscillators recorded in the neocortex with hippocampal θ rhythms, a mechanism by which information distributed across spatially widespread neocortical ensembles can be synchronously transferred to the associative networks of the hippocampus (Sirota et al, 2008).

Recent work has shown that rhythmic activity in cortical circuits controls the precise timing of spike generation. This is accomplished through GABAergic effects on membrane conductance and membrane potential (ie hyperpolarizing inhibitory potentials). The synchronization of synaptic inhibition involves networks of GABAergic neurons and excitatory neurons (Mann and Paulsen, 2007). Recent studies have shown that the GABA cells involved in oscillatory networks are the fast-spiking (FS), parvalbumin-expressing subtype and networks of these cells become robust γ-frequency oscillators (Bartos et al, 2007). BLa neurons exhibit unusual state-related changes in activity that point to functional similarities between the amygdala and hippocampus. In the latter region, the KAR GluR6 subunit is thought to potentially have a role in the generation of γ oscillations (Fisahn et al, 2005). Small changes in the overall activity in CA3 can tilt the balance between excitation and inhibition and cause the neuronal network to switch from γ oscillations to epileptiform bursts. Additionally, GluR6-containing KARs located on the somatodendritic region of both interneurons and pyramidal cells underlie the oscillogenic effects of kainate (Fisahn et al, 2004). Under certain experimental conditions, currents simulating KARs elicit more spiking than currents simulating AMPA receptors (Frerking and Ohliger-Frerking, 2002). Interestingly, AMPA receptor currents, but not those of KARs, could transmit presynaptic θ rhythms into postsynaptic spiking, suggesting that synaptically activated KARs have a strong influence on membrane potential and that both AMPARs and KARs differ in their ability to encode temporal information.

The presence of coherent θ oscillations in the amygdala–hippocampal circuit is thought to potentially favor the emergence of recurring time windows when synaptic interactions may be facilitated in this limbic network (Pare’ and Gaudreau, 1996). It is noteworthy that rhythmic oscillations have also been recorded in the amygdala and seem to show functional similarities to coherent θ in hippocampus, ones that might favor the emergence of recurring time windows when synaptic interactions could potentially be facilitated in this limbic network. There also seems to be an association between rhythmic activity and emotional behaviors. For example, during the anticipation of noxious stimuli, the firing rate of amygdalar neurons increases, and their discharges become more synchronized through a modulation at the θ frequency (Pare and Collins, 2000). The presence of θ oscillations in the lateral amygdala might facilitate cooperative interactions between the amygdala and cortical areas, such as the hippocampus.

There is extensive evidence to suggest that cognitive functions depend on coordination of distributed neural responses, such as perceptual grouping, attention-dependent stimulus selection, subsystem integration, and working memory, and these, in turn, are associated with synchronized oscillatory activity in the θ-, α-, β-, and γ-band (Uhlhaas et al, 2008). In schizophrenia, abnormal oscillations and synchronization seem to be related to cognitive dysfunction and some of the symptoms of the disorder. For example, phase locking of lower-frequency bands (α and θ) has been reported to be significantly reduced in schizophrenics, whereas no significant differences were present in higher frequencies, such as γ and β (Brockhaus-Dumke et al, 2008). In another study, however, evaluations of electroencephalographic EEG parameters after drug treatment in earlier drug-naive schizophrenics showed that lower-frequency θ synchronizations seem to be a state-related phenomenon and that higher γ GFS may be a trait-like phenomenon (Kikuchi et al, 2007).

Both γ and θ oscillations are believed to be important in controlling the timing of neuronal firing in the hippocampus and probably work together to form a neural code, one that is likely abnormal in schizophrenia and related to at least some of its clinical abnormalities (Lisman and Buzsaki, 2008). KARs are critical for the generation of γ oscillations (Fisahn et al, 2004). It is believed that fast field oscillations recorded in the CA1 region reflect summed inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in pyramidal cells as a result of high-frequency barrages from interneurons along the trisynaptic pathway (Ylinen et al, 1995a). Interestingly, the Ih channels have been shown to be involved in pacemaker activity (Robinson and Siegelbaum, 2003) and have the potential to reset the phase currents that comprise oscillatory rhythms (Yang et al, 2007). As discussed below, Ih channels, together with KARs in SO of CA3/2, could potentially contribute to the generation of γ oscillations in the hippocampus (Traub et al, 2003) and influence long-range synchronization (Traub et al, 2004). This latter effect could involve the induction of GABAergic currents by interneurons synaptically interconnected with pyramidal neurons (Palva et al, 2000).

RODENT MODELING FOR CIRCUITRY CHANGES IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

Regulating IPSCs in Pyramidal Neurons in a Schizophrenia Model

The activation of the BLA, either by behavioral stress or by direct electrical stimulation, exerts a biphasic action on hippocampal plasticity with an immediate excitatory effect, followed by a longer-lasting inhibitory effect (Akirav and Richter-Levin, 1999). The assumption that emotional conditions induce long-term neural plasticity in the amygdala suggests that the interrelations between the amygdala and the hippocampus may not be static, but rather dynamic. To learn more about the mechanisms influencing GABA cell activity, a rodent model for abnormal neural circuitry in postmortem studies of schizophrenia has been developed (Benes and Berretta, 2000). As shown in Figure 6, the basic paradigm involves the infusion of picrotoxin (PICRO), a noncompetitive antagonist of the GABAA receptor into a rostral parvocellular division of the BLA in awake, freely moving rats. Projection neurons at this locus send a substantial projection to layer II of ACCx and to the SO of CA3/2. PICRO-treated rats show significant changes in GABAergic interneurons that are remarkably similar to those seen in postmortem studies (Benes et al, 2004). As shown in Figure 6, stimulation of pyramidal cell dendrites in the SR of CA3 results in a sharp decrease in evoked GABA currents and spontaneous, miniature sIPSC amplitude in pyramidal neurons of CA2/3, but not CA1 (Gisabella et al, 2005). This decrease in GABA currents and sIPSC amplitude in this rodent model of SZ represents the first electrophysiological evidence for how a deficit in hippocampal GABA activity in schizophrenia may be generated. These findings are also consistent with a PET imaging study showing increased levels of metabolic activity in the hippocampus of schizophrenic subjects at baseline conditions and during auditory hallucinations (Heckers et al, 1998).

A rodent model of neural circuitry abnormalities in postmortem studies of schizophrenia in which the GABA-A antagonist picrotoxin is infused in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) to mimic a GABA defect in this region. Excitatory projection neurons are stimulated to fire excessively in sector CA3/2. (a) In rat brain, the basolateral amygdala projects preferentially to layer II of the anterior cingulate region and the stratum oriens of sector CA3/2 of the hippocampus; the entorhinal cortex also receives significant inputs from the BLA and has extensive reciprocal connections with the hippocampus. (b) In the hippocampal slice preparation, a stimulating electrode is placed in the stratum radiatum in which mossy fibers project to the apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons. These projections neurons stimulate GABAergic interneurons through recurrent collaterals. These latter cells form inhibitory synaptic connections with the cell bodies of the pyramidal cells in which they induce inhibitory postsynaptic currents. A recording electrode within the pyramidal cell records these responses. (c) IPSC amplitudes are recorded in CA3/2 and CA1 pyramidal cells; however, only those in CA3/2 show robust decreases in IPSCs. See Benes and Berretta (2000) and Gisabella et al (2005) for more details.

Regulating the Membrane Properties of FS Interneurons

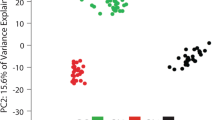

BLA activation is also associated with a lower resting membrane potential and an increased action potential firing rate (Figure 7) in FS interneurons in the SO of CA2/3, but not CA1 (Gisabella et al, 2009). These intracellular recordings in GABA cells further showed that these changes in PICRO-treated rats were associated with an increase of Ih currents. This is consistent with the postmortem finding of increased expression of mRNA for these channels in GABA cells at this same locus in schizophrenics (see above). A number of studies have shown that the Ih current has a role in determining membrane potential, GABA release, action potential firing characteristics, hyperpolarizing events and rebound excitation, and other intrinsic properties of interneurons (Aponte et al, 2006; Lupica et al, 2001; McCormick and Pape, 1990; Meldrum and Rogawski, 2007; Pape, 1996; Surges et al, 2004; van Welie et al, 2004). Activation of Ih current is important in establishing the rhythmicity and stabilization of complex neuronal circuits (Bayliss et al, 1994; Dickson et al, 2000; Luthi and McCormick, 1998; Pape, 1996; Strata et al, 1997; Washio et al, 1999). Ih is expressed in CA2/3 of the developing and mature HIPP by both pyramidal cells (Bender et al, 2001; Maccaferri et al, 1993) and inhibitory interneurons (Lupica et al, 2001; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996a; Strata et al, 1997). Most Ih channels in pyramidal cells are located in distal dendrites and the Ih recordings might be distorted because of the great electronic distance between dendrites and the soma where recordings are performed in slices (De Miranda et al, 2000). In GABAergic cells, on the other hand, this problem is more limited, because interneurons have relatively short dendritic branches and therefore are more electrotonically compact. Interestingly, the Ih channel is also linked to pathological hyperexcitability (Chen et al, 2001a; Di Pasquale et al, 1997), in which it seems to control the balance of inhibition and excitation, particularly in the limbic system. In PICRO-infused animals, the observed increase of Ih amplitude (Figure 7) is consistent with the decreased resting membrane potential and increased frequency of firing seen in FS GABA cells.

Single-cell recordings from fast-spiking interneurons in the stratum oriens (SO) of sector CA3/2 in rats receiving picrotoxin (PICRO) infusions in the basolateral amygdala (BLA). (a, b) The spike frequency of fast-spiking neurons in PICRO-treated rats is significantly greater than that seen in rats receiving saline infusions, suggesting that BLA afferents to CA3/2 are capable of stimulating this population of GABA cell to fire more robustly. (b, c) The Ih channel (HCN3), which shows an increased expression in stratum oriens of CA3/2 in schizophrenics, also shows an increase in its amplitude at this same locus in PICRO-treated rats. (d) This effect is not observed in fast-spiking neurons in stratum oriens of CA1, providing further support for the validity of this model for studying neural circuitry abnormalities in schizophrenia. See Gisabella et al (2009) for more details.

These changes would make interneurons more excitable and decrease the threshold needed for them to fire action potentials with greater frequency. If so, why would there be a decrease in IPSCs and sIPSC amplitude in the postsynaptic pyramidal neuron (Gisabella et al, 2005), as reported earlier? As shown in Figure 8, heightened stimulation GABAergic axosomatic synapses on pyramidal neurons could result in terminals that are depleted of transmitter (Berretta et al, 2001). The intrinsic circuitry within this locus could become dysfunctional if GABA cell terminals become depleted of transmitter (Berretta et al, 2001). It is also possible that their somata become oxidatively stressed by chronically heightened excitatory drive related to KARs (Coyle and Puttfarcken, 1993). As noted earlier, expression of the GluR6 and 7 subunits of the KAR do show increased expression in SO of CA3/2 of schizophrenics (Benes et al, 2007). Is it possible that the observed increase of Ih current in rats receiving a PICRO infusion in the BLA may be, at least in part, related to increases in the expression of KAR subunits? A recent study in the rodent HIPP has shown that KARs have been associated with the modulation of Ih currents (Dugladze et al, 2007). Further studies will be needed to establish whether such a regulatory mechanism exists in GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus, particularly at the key locus in CA3/2 implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

A model diagram depicting changes in the modulation of GABAergic interneurons and pyramidal cells in the stratum oriens of sectors CA3/2 of normal controls and in the schizophrenia model. Excitatory afferent fibers from the basolateral amygdala (BLA) project to the apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons and to dendritic branches of fast-spiking GABA cells. When induced to fire, the GABAergic synapses on the pyramidal cell cause spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) to be generated in the cell body of the pyramidal cell. In the schizophrenia model, the GABA cells show an increase in Ih channels and their spike frequency. The pyramidal cells show a decrease in spontaneous IPSCs, rather than an increase. Consistent with this, a decrease in GABAergic synapses surrounding pyramidal neurons is shown in the photomicrographic inset in the middle of the diagram, suggesting that there may be a depletion of GABA in these synaptic terminals. In neural circuits, sometimes ‘more’ results in ‘less’. See Gisabella et al (2009) for more details.

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of evidence obtained from in vivo brain imaging, postmortem, and rodent studies, it seems likely that amygdalocortical circuitry probably has an important function in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. MRI studies suggest that volume loss may be present not only in the amygdala, but also in the ACCx and hippocampus and may reflect clinical dysfunction in this disorder. Postmortem studies are suggesting that disturbances of GABAergic neurons located in layer II off ACCx and the SO of sectors CA3/2, respectively, may be related to increased excitatory afferent activity from BLA projections to these loci. Parallel changes in the glutamatergic, cholinergic, and dopaminergic innervations underscore the importance of obtaining a detailed understanding of the microcircuitry within these key brain regions. Additionally, it is becoming increasingly clear that a variety of growth factors and signaling pathways are probably contributing to the abnormal expression of GAD67 in vulnerable populations of GABAergic interneurons.

By learning more about the ways in which key neural circuits, such as the trisynaptic pathway, are altered in schizophrenia, it is becoming increasingly possible to generate heuristic models that can be used to validate and extend our understanding of neural circuitry abnormalities in schizophrenia. In one such model discussed here, a combination of microscopic, molecular, and electrophysiological approaches are being used to investigate how the membrane properties and electrophysiological responses of GABAergic neurons may be related to abnormal amounts of excitatory afferent activity and the induction of gene expression changes in these interneurons. Excitatory activity generated within the BLA and transmitted to the HIPP may be a key variable for understanding how the GABA cell phenotype is maintained and how the frequency and amplitude of oscillatory rhythms may be altered in the hippocampus of schizophrenics. The fact that BLA fibers are normally maturing and sprouting during the period when the schizophrenic prodrome becomes manifest lays the groundwork for understanding how the GABA cell phenotype may be disrupted at a critical stage of the postnatal period. It has become clear that the molecular pathology of neural circuitry in schizophrenia is multidimensional in nature and its elucidation will require multidisciplinary strategies.

Future Directions

The studies described above suggest that key components of the limbic lobe are an important focus for the study of schizophrenia. By applying a variety of molecular and genetic strategies to the study of amygdalocortical circuitry in human subjects with schizophrenia and in rodent models, it will be possible to expand our understanding of how GABAergic interneurons are regulated in both health and disease. On the basis of a variety of features, including their location within specific layers and sectors, their neuropeptide content, and their electrical properties, complex molecular models will be useful in explaining how these subtypes interact with one another, and with principle projection neurons. The segregation of interneuronal subtypes from one another using LMD and highly sensitive and specific molecular tools, is proving to be a powerful approach for uncovering abnormal regulatory changes that are present in GABA cells in schizophrenia. A key objective of this research will continue to be the identification of target genes that are involved in the dysfunction of these neurons. Most importantly, it will be critical to cross the great divide between molecular neuroscience and genetics. In the course of clinically identifying the genes that are involved in schizophrenia, it can be inferred that there are corollary changes in the molecular regulation of complex circuits, such as the trisynaptic pathway, with which they are associated. Critical questions will emerge from this process. When during the life cycle are these ‘schizophrenia’ genes being expressed and where in the corticolimbic system are they causing disruptions in the regulation of information processing?

We can think of susceptibility as a genetic construct, one that must be translated into neurobiologic terms so that the molecular pathology of schizophrenia can be clearly defined. When we have an in depth understanding of the operational relationship that exists between susceptibility genes and susceptible circuits, the path toward novel treatment strategies for this disorder will have greater clarity.

DISCLOSURE

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Acsady L, Arabadzisz D, Freund TF (1996). Correlated morphological and neurochemical features identify different subsets of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive interneurons in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 73: 299–315.

Acsady L, Kamondi A, Sik A, Freund T, Buzsaki G (1998a). - GABAergic cells are the major postsynaptic targets of mossy fibers in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 18: 3386–3403.

Acsady L, Kamondi A, Sik A, Freund T, Buzsaki G (1998b). GABAergic cells are the major postsynaptic targets of mossy fibers in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 18: 3386–3403.

Adamec RE (1978). Normal and abnormal limbic system mechanism of emotive biasing. In: Livingston KE, Hornykiewicz O (eds). Limbic Mechanisms. Plenum Press: New York, NY. pp 405–455. The first evidence from well-controlled experiments in animals demonstrating the role of the amygdala in emotion..

Adamec RE (1991). Individual differences in temporal lobe sensory processing of threatening stimuli in the cat. Physiol Behav 49: 445–464.

Aggleton JP (1993). The contribution of the amygdala to normal and abnormal emotional states. Trends Neurosci 16: 328–333.

Akbarian S, Kim JJ, Potkin SG, Hagman JO, Tafazzoli A, Bunney WE et al. (1995). Gene expression for glutamic acid decarboxylase is reduced without loss of neurons in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52: 258–278. The first postmortem study providing empiric support for the hypothesis that there is a GABA defect in schizophrenia.

Akhondzadeh S, Mojtahedzadeh V, Mirsepassi GR, Moin M, Amini-Nooshabadi H, Kamalipour A (2002). Diazoxide in the treatment of schizophrenia: novel potassium channel openers in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Pharm Ther, 27: 453–459.

Akirav I, Richter-Levin G (1999). Biphasic modulation of hippocampal plasticity by behavioral stress and basolateral amygdala stimulation in the rat. J Neurosci 19: 10530–10535.

Aleman A, Kahn RS (2005). Strange feelings: do amygdala abnormalities dysregulate the emotional brain in schizophrenia? Prog Neurobiol 77: 283–298.

Amaral DG, Insausti R (1992). Retrograde transport of D-[3H]-aspartate injected into the monkey amygdaloid complex. Exp Brain Res 88: 375–388.

Amzica F, Steriade M (1995). Disconnection of intracortical synaptic linkages disrupts synchronization of a slow oscillation. J Neurosci 15: 4658–4677.

Aponte Y, Lien CC, Reisinger E, Jonas P (2006). Hyperpolarization-activated cation channels in fast-spiking interneurons of rat hippocampus. J Physiol 574: 229–243.

Attisano L, Wrana JL (2002). Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science 296: 1646–1647.

Backman M, Machon O, Mygland L, van den Bout CJ, Zhong W, Taketo MM et al. (2005). Effects of canonical Wnt signaling on dorso-ventral specification of the mouse telencephalon. Dev Biol 279: 155–168.

Barrelet L, Ferrero F, Szogethy L, Giddey C, Pellizzer G (1990). Expressed emotion and first-admission schizophrenia nine-month follow-up in a French cultural environment. Br J Psychiatry 156: 357–362.

Bartos M, Vida I, Honas P (2007). Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat Rev 8: 45–56.

Bayliss DA, Viana F, Bellingham MC, Berger AJ (1994). Characteristics and postnatal development of a hyperpolarization-activated inward current in rat hypoglossal motoneurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 71: 119–128.

Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Lee GP (1999). Different contributions of the human amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to decision-making. J Neurosci 19: 5473–5481.

Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H, Adolphs R, Rockland C, Damasio AR (1995). Double dissociation of conditioning and declarative knowledge relative to the amygdala and hippocampus in humans. Science 269: 1115–1118.

Bender RA, Brewster A, Santoro B, Ludwig A, Hofmann F, Biel M et al. (2001). Differential and age-dependent expression of hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel isoforms 1-4 suggests evolving roles in the developing rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 106: 689–698.

Benes FM (1993). Relationship of cingulate cortex to schizophrenia. In: Vogt BA, Gabriel M (eds). Neurobiology of Cingulate Cortex and Limbic Thalamus. Birkhauser: Boston, MA. pp 581–605.

Benes FM (1989). Myelination of cortical-hippocampal relays during late adolescence. Schizophr Bull 15: 585–593.

Benes FM, Cunningham MG, Berretta S, Gisabella B (2009). Course and pattern of cingulate pathology in schizophrenia. In: Vogt BA (ed). Cingulate Neurobiology and Disease. Oxford University Press. pp. 679–705.

Benes FM, Berretta S (2000). Amygdalo-entorhinal inputs to the hippocampal formation in relation to schizophrenia. In: Scharfman HE, Witter MP, Schwarcz R (eds). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Academy of Sciences: New York, NY. pp 293–304.

Benes FM, Berretta S (2001). GABAergic interneurons: implications for understanding schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 25: 1–27.

Benes FM (1987) An analysis of the arrangement of neurons in the cingulate cortex of schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 44: 608–616.

Benes FM, Burke RE, Walsh J, Berretta S, Matzilevich D, Minns M et al. (2004). Acute amygdalar activation induces an upregulation of multiple monoamine G protein coupled pathways in rat hippocampus. Mol Psychiatry 9: 932–945, 895.

Benes FM, Khan Y, Vincent SL, Wickramasinghe R (1996a). Differences in the subregional and cellular distribution of GABAA receptor binding in the hippocampal formation of schizophrenic brain. Synapse 22: 338–349.

Benes FM, Kwok EW, Vincent SL, Todtenkopf MS (1998). A reduction of nonpyramidal cells in sector CA2 of schizophrenics and manic depressives. Biol Psychiatry 44: 88–97.

Benes FM, Lim B, Matzilevich D, Subburaju S, Walsh JP (2008). Circuitry-based gene expression profiles in GABA cells of the trisynaptic pathway in schizophrenics versus bipolars. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20935–20940. This paper presents the first neural circuitry model of schizophrenia derived from quantitative microscopic studies.

Benes FM, Lim B, Matzilevich D, Walsh JP, Subburaju S, Minns M (2007). Regulation of the GABA cell phenotype in hippocampus of schizophrenics and bipolars. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 10164–10169. The first demonstration that a complex molecular network playing a pivotal role in the regulation of GAD67 and the GABA cell phenotype is abnormal in schizophrenia.

Benes FM, Majocha R, Bird ED, Marotta CA (1987). Increased vertical axon numbers in cingulate cortex of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44: 1017–1021.

Benes FM, McSparren J, Bird ED, SanGiovanni JP, Vincent SL (1991). Deficits in small interneurons in prefrontal and cingulate cortices of schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48: 996–1001. First evidence for a loss of GABA cells in schizophrenia.

Benes FM, Sorensen I, Vincent SL, Bird ED, Sathi M (1992a). Increased density of glutamate-immunoreactive vertical processes in superficial laminae in cingulate cortex of schizophrenic brain. Cereb Cortex 2: 503–512. This paper presents the first neural circuitry model of schizophrenia derived from quantitative microscopic studies.

Benes FM, Todtenkopf MS (1999). Effect of age and neuroleptics on tyrosine hydroxylase-IR in sector CA2 of schizophrenic brain. Neuroreport 10: 3527–3530.

Benes FM, Todtenkopf MS, Kostoulakos P (2001a). GluR5,6,7 subunit immunoreactivity on apical pyramidal cell dendrites in hippocampus of schizophrenics and manic depressives. Hippocampus 11: 482–491.

Benes FM, Todtenkopf MS, Taylor JB (1997a). Differential distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase fibers on small and large neurons in layer II of anterior cingulate cortex of schizophrenic brain. Synapse 25: 80–92.

Benes FM, Vincent SL, Alsterberg G, Bird ED, SanGiovanni JP (1992b). Increased GABAA receptor binding in superficial layers of cingulate cortex in schizophrenics. J Neurosci 12: 924–929. The first demonstration that a GABA defect in schizophrenia is accompanied by a compensatory upregulation of the GABA-A receptor on postsynaptic pyramidal neurons.

Benes FM, Vincent SL, Marie A, Khan Y (1996b). Up-regulation of GABAA receptor binding on neurons of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Neuroscience 75: 1021–1031.

Benes FM, Vincent SL, Todtenkopf M (2001b). The density of pyramidal and nonpyramidal neurons in anterior cingulate cortex of schizophrenic and bipolar subjects. Biol Psychiatry 50: 395–406.

Benes FM, Wickramasinghe R, Vincent SL, Khan Y, Todtenkopf M (1997b). Uncoupling of GABA(A) and benzodiazepine receptor binding activity in the hippocampal formation of schizophrenic brain. Brain Res 755: 121–129.

Berretta S, Munno DW, Benes FM (2001). Amygdalar activation alters the hippocampal GABA system: ‘partial’ modelling for postmortem changes in schizophrenia. J Comp Neurol 431: 129–138. The first demonstration of a rodent model based on postmortem abnormalities of neural circuitry in schizophrenia.

Bleuler E (1952). Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. International Press: New York, NY.

Bortolotto ZA, Lauri S, Isaac JT, Collingridge GL (2003). Kainate receptors and the induction of mossy fibre long-term potentiation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 358: 657–666.

Bragin A, Jand G, Nadasdy Z, Hetke J, Wise K, Buzsaki G (1995a). - Gamma (40-100 Hz) oscillation in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. J Neurosci 15: 47–60.

Bragin A, Jando G, Nadasdy Z, Hetke J, Wise K, Buzsaki G (1995b). Gamma (40-100 Hz) oscillation in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. J Neurosci 15: 47–60.

Broca P (1878). Anatomie comparee des circonvolutions cerebrales: Le grand lobe limbique et la scissure limbique dans la serie des manmiferes. Rev Anthropol 1: 385–498.

Brockhaus-Dumke A, Mueller R, Faigle U, Klosterkoetter J (2008). Sensory gating revisited: relation between brain oscillations and auditory evoked potentials in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 99: 238–249.

Bucci P, Mucci A, Merlotti E, Volpe U, Galderisi S (2007). Induced gamma activity and event-related coherence in schizophrenia. Clin EEG Neurosci 38: 96–104.

Burle B, Bonnet M (2000). High-speed memory scanning: a behavioral argument for a serial oscillatory model. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 9: 327–337.

Buzsaki G (1997). Functions for interneuronal nets in the hippocampus. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 75: 508–515.

Buzsaki G, Eidelberg E (1983). Phase relations of hippocampal projection cells and interneurons to theta activity in the anesthetized rat. Brain Res 266: 334–339.

Buzsaki G, Horvath Z, Urioste R, Hetke J, Wise K (1992). High-frequency network oscillation in the hippocampus. Science 256: 1025–1027.

Cahill L, Haier RJ, Fallon J, Alkire MT, Tang C, Keator D et al. (1996). Amygdala activity at encoding correlated with long-term, free recall of emotional information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 8016–8021. Early demonstration that the amygdala plays a role in emotional learning.

Cahill L, McGaugh JL (1996). The neurobiology of memory for emotional events: adrenergic activation and the amygdala. Proc West Pharmacol Soc 39: 81–84.

Chen K, Aradi I, Thon N, Eghbal-Ahmadi M, Baram TZ, Soltesz I (2001a). Persistently modified h-channels after complex febrile seizures convert the seizure-induced enhancement of inhibition to hyperexcitability. Nat Med 7: 331–337.

Chen S, Wang J, Siegelbaum SA (2001b). Properties of hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker current defined by coassembly of HCN1 and HCN2 subunits and basal modulation by cyclic nucleotide. J Gen Physiol 117: 491–504.

Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P (1993). Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders [Review]. Science 262: 689–695.

Crepel V, Khazipov R, Ben-Ari Y (1997). Blocking GABA(A) inhibition reveals AMPA- and NMDA-receptor-mediated polysynaptic responses in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 77: 2071–2082.

Csicsvari J, Jamieson B, Wise KD, Buzsaki G (2003). Mechanisms of gamma oscillations in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. Neuron 37: 311–322.

Cunningham MC, Bhattacharyya S, Benes FM (2007). Increasing interaction of amygdalar afferents with GABAergic interneurons between birth and adulthood. Cereb Cortex, in press.

Cunningham MG, Bhattacharyya S, Benes FM (2002). Amygdalo-cortical sprouting continues into early adulthood: implications for the development of normal and abnormal function during adolescence. J Comp Neurol 453: 116–130. The first demonstration that the basolateral amygdala afferents to the medial prefrontal cortex continue to sprout and form excitatory synaptic connections with the spines of pyramidal neurons.

Cunningham MG, Bhattacharyya S, Benes FM (2008). Increasing Interaction of amygdalar afferents with GABAergic interneurons between birth and adulthood. Cereb Cortex 18: 1529–1535. The first demonstration that fibers from the basolateral amygdala continue to form interactions with GABAergic interneurons during the equivalent of adolescence.

Damasio AR, Van Hoesen GW (1983). Emotional disturbances associated with focal lesions of the limbic frontal lobe. In: Heilman KM, Satz P (eds). Neuropsychology of Human Emotion. The Guilford Press: New York, NY. pp 85–110.

Davis M (1992). The role of the amygdala in fear-potentiated startle: implications for animal models of anxiety. Trends Pharmacol Sci 13: 35–41. The first experimental evidence suggesting that the amygdala plays a key role in conditioned behaviors similar to those seen in anxiety states.

Davis M (1994). The role of the amygdala in emotional learning. Int Rev Neurobiol 36: 225–266.

De Miranda J, Santoro A, Engelender S, Wolosker H (2000). Human serine racemase: moleular cloning, genomic organization and functional analysis. Gene 256: 183–188.

Di Pasquale E, Keegan KD, Noebels JL (1997). Increased excitability and inward rectification in layer V cortical pyramidal neurons in the epileptic mutant mouse Stargazer. J Neurophysiol 77: 621–631.

Dickson CT, Magistretti J, Shalinsky MH, Fransen E, Hasselmo ME, Alonso A (2000). Properties and role of I(h) in the pacing of subthreshold oscillations in entorhinal cortex layer II neurons. J Neurophysiol 83: 2562–2579.