Abstract

Alzheimer’s dementia is a devastating and incurable disease afflicting over 35 million people worldwide. Amyloid-β (Aβ), a key pathogenic factor in this disease, has potent cerebrovascular effects that contribute to brain dysfunction underlying dementia by limiting the delivery of oxygen and glucose to the working brain. However, the downstream pathways responsible for the vascular alterations remain unclear. Here we report that the cerebrovascular dysfunction induced by Aβ is mediated by DNA damage caused by vascular oxidative–nitrosative stress in cerebral endothelial cells, which, in turn, activates the DNA repair enzyme poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase. The resulting increase in ADP ribose opens transient receptor potential melastatin-2 (TRPM2) channels in endothelial cells leading to intracellular Ca2+ overload and endothelial dysfunction. The findings provide evidence for a previously unrecognized mechanism by which Aβ impairs neurovascular regulation and suggest that TRPM2 channels are a potential therapeutic target to counteract cerebrovascular dysfunction in Alzheimer’s dementia and related pathologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) has emerged as one of the major public health challenges of our times. Despite being a leading cause of death1, no disease-modifying treatment is available, and its impact will continue to grow, reaching epidemic proportions in the next several decades2. Accumulating evidence supports a role of cerebrovascular factors in the pathogenesis of AD3,4,5. Midlife vascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes and obesity, increase the risk for AD later in life6,7. Autopsy studies have shown that mixed ischaemic and amyloid pathologies often coexist in the same brain, and that ischaemic lesions greatly amplify the negative impact of amyloid on cognition8,9. AD is associated with reductions in cerebral blood flow (CBF) early in the course of the disease10,11,12, as well as impairment of the ability of endothelial cells to regulate blood flow in systemic vessels5,13. In support of their pathogenic role, controlling vascular risk factors can slow down the progression of AD14 and may have contributed to dampen the rise in AD prevalence15.

Extracellular accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ), a 40–42 amino-acid peptide derived from the amyloid precursor protein (APP), is a key pathogenic factor in AD. However, the mechanisms leading to the brain dysfunction underlying dementia remain to be fully established. In addition to its deleterious neuronal effects16, Aβ exerts potent actions on cerebral blood vessels4,5. Thus, Aβ1–40 constricts blood vessels and impairs endothelial function, blood–brain barrier permeability and neurovascular coupling, a vital cerebrovascular response matching the increase in the energy demands imposed by neural activity with the delivery of substrates through CBF17,18,19,20. The mechanisms of the cerebrovascular effects involve activation of innate immunity receptors21,22,23, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by a NOX2-containing NADPH oxidase24,25.

The cationic nonselective channel transient receptor potential melastatin-2 (TRPM2) is an important regulator of endothelial Ca2+ homeostasis26,27. Thus, opening of the channel leads to a large Ca2+ influx that has a deleterious impact on endothelial function and survival28,29. A defining feature of this channel is the presence of a C-terminus Nudix domain, which is responsible for its unique gating by (ADP)-ribose (ADPR)28,30. Aβ1–40 leads to cerebrovascular accumulation of peroxynitrite, the reaction product of nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide31,32, which could induce DNA damage and activation of poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP) and poly(ADP)-ribose glycohydrolase (PARG)32. Since PARP/PARG activity is a major source of ADPR32,33, it is conceivable that Aβ-induced PARP/PARG activation in cerebral blood vessels leads to opening of potentially damaging endothelial TRPM2 channels. In the present study, we report that the endothelial dysfunction produced by Aβ1–40 depends critically on nitrosative stress, PARP activity and TRPM2 channels, resulting in massive increases in intracellular Ca2+. The findings identify TRPM2 currents as a heretofore-unrecognized effector of Aβ1–40-induced endothelial vasomotor failure, and suggest that the TRPM2 channel is a putative therapeutic target for the neurovascular impairment associated with AD and related diseases.

Results

Peroxynitrite mediates Aβ-induced vasomotor dysfunction

First, we sought to determine whether Aβ1–40 induces nitration in the arterioles of the neocortical region in which CBF was studied, and, if so, whether such nitration contributes to the vasomotor dysfunction. Superfusion of the somatosensory cortex with Aβ1–40 increased 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) immunoreactivity, a marker of peroxynitrite, in penetrating arterioles (Fig. 1a). The 3-NT increase was suppressed by the ROS scavenger Mn(III)tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin Chloride (MnTBAP) or the NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor L-NG-Nitroarginine (L-NNA), and in NOX2-null mice (Fig. 1b), consistent with peroxynitrite being the source of the nitration. Aβ1–40 also reduced resting CBF and attenuated the CBF increase produced by neural activity (whisker stimulation), by the endothelium-dependent vasodilator acetylcholine and the NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 1A). Responses to adenosine and hypercapnia were not affected (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 1A), attesting to the selectivity of the impairment of endothelial-dependent relaxation and neurovascular coupling. Next, we investigated whether peroxynitrite is involved in the vasomotor dysfunction. Neocortical application of the peroxynitrite scavenger uric acid (UA) or the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato Iron (III), Chloride (FeTPPS), but not its inactive form TPPS, prevented the attenuation in the cerebrovascular responses (Fig. 1c). FeTPPS and UA also prevented Aβ-induced vascular 3-NT formation (Fig. 1b). UA and L-NNA did not attenuate Aβ-induced ROS formation (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the suppression of nitration by these agents was not due to ROS scavenging. Thus, peroxynitrite formation in cerebral blood vessels is needed for the cerebrovascular effects of Aβ.

3-NT immunoreactivity, a marker of peroxynitrite, induced by neocortical superfusion of Aβ1–40 (Aβ, 5 μM) increases in CD31-positive penetrating arterioles in the somatosensory cortex (arrows; a). The nitration is suppressed by local application of the free radical scavenger MnTBAP, the NOS inhibitor L-NNA, the peroxynitrite scavenger UA or the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTPPS, and in mice lacking the Nox2 subunit of NADPH oxidase (b). Neocortical superfusion of Aβ1–40 attenuates resting CBF and the increase in CBF induced by whisker stimulation or acetylcholine, but not by adenosine. The attenuation is prevented by treatment of UA or FeTPPS, but not its inactive version TPPS (c). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05 from control, analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=5 per group.

The microvascular effects of Aβ require PARP/PARG activity

Since nitrosative stress activates PARP31,32, we investigated whether PARP is involved in the neurovascular effects of Aβ. Neocortical application of the PARP inhibitor PJ34 reversed the cerebrovascular alterations induced by Aβ (Fig. 2a–c; Supplementary Fig. 1B). Furthermore, Aβ superfusion did not alter cerebrovascular reactivity in PARP-1 null mice (Fig. 2). Next, we examined whether PARP is also involved in the neurovascular alterations observed in transgenic mice overexpressing APP (tg2576)22,24,25. Superfusion of PJ34 attenuated PARP activity in the underlying neocortex and ameliorated the cerebrovascular dysfunction (Fig. 3a,b). Superfusion of the PARG inhibitor adenosine 5′-diphosphate (Hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidinediol, NH4 (ADP-DPH) also counteracted the cerebrovascular dysfunction both in wild-type (WT) mice with Aβ superfusion and in tg2576 mice (Figs 2 and 3). These findings, collectively, implicate the activity of the PARP/PARG pathway in the mechanisms of neurovascular alterations induced by Aβ.

Neocortical superfusion of Aβ1–40 (Aβ) attenuates resting CBF (a), and the CBF increase evoked by whisker stimulation (b) or acetylcholine (c) in PARP-1+/+ mice. The response to adenosine is not affected (d). The vascular effects of Aβ1–40 are reversed by neocortical application of the PARP inhibitor PJ34 or the PARG inhibitor APD-DPH, and are not observed in PARP-1−/− mice. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. a.u., arbitrary unit; *P<0.05, analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=5 per group.

The increase in CBF evoked by whisker stimulation or ACh is attenuated in tg2576 mice, while responses to adenosine and hypercapnia are not affected (a). The cerebrovascular dysfunction is reversed by neocortical application of the PARP inhibitor PJ34 or the PARG inhibitor APD–DPH (a). PJ34 suppresses the increase in PARP activity observed in penetrating pial arterioles of tg2576 mice (arrows). Sections were counterstained with methyl green (b). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05 from WT vehicle, analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=5 per group.

Aβ induces brain endothelial DNA damage and PARP activation

Next, we focused on the cellular mechanisms through which Aβ-induced nitrosative stress leads to PARP activation and endothelial dysfunction. To this end, we first examined whether Aβ-induced nitrosative stress leads to DNA damage and PARP activation. Treatment of brain endothelial cell cultures with Aβ (300 nM), but not its scrambled version, increased the DNA damage marker phospho-γH2A.X, PARP activity and the formation of the PARP reaction product PAR (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. 3). The phospho-γH2A.X immunoreactivity appeared as nuclear puncta reflecting the sites of DNA damage, whereas the PARP activity signal was more diffuse (Fig. 4), suggesting a broader distribution of PARP reaction products. These effects of Aβ were abolished by ROS scavengers (tempol, MnTBAP), NADPH oxidase inhibition (gp91ds-tat), NOS inhibition (L-NNA) and by the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTPPS or PARP inhibition (PJ34; Fig. 4c–e). Thus, Aβ leads to endothelial DNA damage and PARP activation via oxidative–nitrosative stress.

In brain endothelial cell cultures, Aβ1–40 (Aβ; 300 nM), but not scrambled Aβ1–40 (scAβ), increases ϒH2AX fluorescence, a marker of DNA damage (a–c), PARP activity (a,b,d) and PAR formation (a,b,e). The increases are dampened by the ROS scavengers Tempol and MnTBAP, the NADPH oxidase peptide inhibitor gp91ds-tat, the NOS inhibitor L-NNA and the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst FeTPPS (c–e). PARP activity (d) and PAR formation (e) are also attenuated by the PARP inhibitor PJ34. To-Pro-3 is a marker of cell nuclei. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05; analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=30–40 cells per group.

Aβ triggers endothelial TRPM2 currents and Ca2+ increases

PAR produced by PARP activity is cleaved to ADPR by PARG33. Since ADPR is a potent activator of TRPM2 channels34, we examined whether Aβ opens the channels through this mechanism. Abundant TRPM2 immunoreactivity was observed in brain endothelial cells (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Fig. 4). Aβ, as well as ADPR, injected intracellularly through the patch pipette, induced inward currents blocked by the TRPM2 antagonists N-(p-Amylcinnamoyl)anthranilic acid (ACA) and 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), or by TRPM2 knockdown using short interfering RNA (siRNA; Fig. 5b–d; Supplementary Fig. 5). Analysis of current–voltage relationships demonstrated the conductance characteristics of TRPM2 channels (Fig. 5b)28,35. Consistent with an involvement of NADPH oxidase-derived ROS, NO and peroxynitrite, Aβ-induced TRPM2 currents were blocked by MnTBAP, gp91ds-tat and L-NNA (Fig. 5d). In addition, Aβ-induced currents were attenuated by PJ34 and by the PARG inhibitor ADP-HPD, pointing to an involvement of PARP and PARG (Fig. 5d). ADPR currents were not attenuated by these antagonists (Fig. 5d), ruling out a direct effect of these drugs on the channel. Since activation of TRPM2 leads to massive increases in Ca2+ into the cells and endothelial cell dysfunction28,29,35, we tested whether Aβ increases intracellular Ca2+ through TRPM2 channels. Aβ increased intracellular Ca2+, an effect attenuated by pretreatment with 2-APB or ACA, and by TRPM2 knockdown (Fig. 6). The effect was dependent on extracellular Ca2+ and was larger than that produced by the well-established TRPM2 activator H2O2 at concentrations of 0.5–1 mM (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7). These observations, collectively, indicate that Aβ induces TRPM2 currents in endothelial cells, which are mediated by PARP and PARG activity and lead to large and sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+.

TRPM2 is expressed in CD31-positive brain endothelial cell cultures (bEnd.3 cells; see Supplementary Fig. 4 for the specificity of the immunostain) (a). Aβ1–40 (Aβ) and the channel activator ADPR induce inward currents with the conductance characteristics of TRPM2 currents (b). The currents are blocked by the TRPM2 inhibitor 2-APB or 2-ACA, or TRPM2 knockdown (b–d). Aβ-induced TRPM2 currents are antagonized by the ROS scavenger MnTBAP, the NADPH oxidase peptide inhibitor gp91ds-tat, the NOS inhibitor L-NNA, the PARP inhibitor PJ34 and the PARG inhibitor ADP-HPD. ADPR-induced TRPM2 currents are unaffected by these antagonists. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05; #P<0.05 from Aβ1–40-induced currents; analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=4–24 cells per group.

The Aβ1–40 (Aβ)-induced increases in intracellular Ca2 are attenuated by the mechanistically distinct TRPM2 inhibitors 2-APB and ACA (a,c) or by TRPM2 knockdown using siRNA, but not control siRNA (control si) (b,d). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05; analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=6–10 per group.

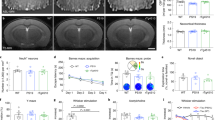

TRPM2 contributes to Aβ-induced neurovascular dysfunction

To investigate the potential involvement of TRPM2 channels in vivo, we examined the effect of neocortical application of 2-APB or ACA on the endothelial dysfunction induced by Aβ. These TRPM2 inhibitors did not affect resting cerebrovascular responses but prevented the cerebrovascular effects of Aβ in WT mice and reversed the cerebrovascular dysfunction observed in tg2576 mice (Fig. 7). Similarly, the cerebrovascular dysfunction was not observed in TRPM2-null mice (Fig. 8), providing nonpharmacological evidence for a critical involvement of these channels in the neurovascular and endothelial alterations induced by the Aβ peptide also in vivo.

Neocortical application of 2-APB or ACA has no effect on resting CBF (a), but it prevents the reduction in resting CBF induced by neocortical superfusion of Aβ1–40 (Aβ) (a). 2-APB or ACA also rescues the attenuation in the CBF increase evoked by whisker stimulation (b) or acetylcholine (c) induced by Aβ1–40 or observed in tg2576 mice. The CBF increase induced by adenosine is unaffected (d). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05; analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=5–6 per group.

Neocortical superfusion of Aβ1–40 (Aβ) does not attenuate resting CBF (a), or the increase in CBF induced by whisker stimulation (b) or acetylcholine (c) in TRPM2-null mice. Responses to adenosine were not altered (d). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05; analysis of variance and Tukey’s test; N=5 per group.

Discussion

We used in vivo and in vitro approaches to investigate the downstream mechanisms of the cerebrovascular dysfunction induced by Aβ. Several new findings were obtained. First, we provided evidence for a critical role of peroxynitrite in the mechanisms of the dysfunction. Second, we found that PARP activity is required for the cerebrovascular effects of Aβ, both in a neocortical application model and in APP-overexpressing mice. Third, we established that Aβ rapidly induces DNA damage, PARP activation and PAR formation in endothelial cells, effects triggered by oxidative–nitrosative stress. Fourth, we demonstrated that Aβ activates a typical TRPM2 channel conductance in endothelial cells leading to intracellular Ca2+ overload. Fifth, we provided evidence that such TRPM2 activation depends on oxidative–nitrosative stress and requires PARP and PARG activity. Sixth, we demonstrated that TRPM2 channels are also involved in the deleterious effects of Aβ on endothelial function in vivo. These novel observations, collectively, implicate, for the first time, PARP and TRPM2 channels in the endothelial and neurovascular dysfunction induced by Aβ and provide evidence for a previously unappreciated mechanism by which Aβ-induced oxidative–nitrosative stress alters cerebrovascular regulation in models of AD.

We found that the peroxynitrite scavenger FeTPPS and UA prevent the vascular nitration and counteract the cerebrovascular dysfunction in full. These agents did not affect vascular ROS production, ruling out that their effects on nitration and CBF regulation were secondary to suppression of oxidative stress. Although it was already established that Aβ induces nitrosative stress in cerebral arterioles19,31, it was not known whether peroxynitrite contributes to the dysfunction and, if so, through which mechanisms. Since peroxynitrite induces DNA double-strand breaks32,33,36, we explored whether activation of the DNA repair enzyme PARP was involved in the dysfunction. We found that PARP inhibition completely reverses the deleterious vascular effects of exogenous Aβ, and that Aβ does not disrupt cerebrovascular function in PARP-1-null mice. Furthermore, PARP inhibition fully reversed the vascular impairment observed in tg2576 mice. These findings, collectively, provide evidence that Aβ-induced peroxynitrite formation and subsequent PARP activation are critical factors, downstream of ROS, responsible for the cerebrovascular dysfunction.

Having established that PARP activity is needed for the alterations in vascular regulation in vivo, we used endothelial cell cultures to investigate the cellular mechanisms of the effect. As suggested by the results in vivo, Aβ produced DNA damage, PARP activation and PAR formation in endothelial cultures. PARP activation in energy-starved tissue has been thought to contribute to cell dysfunction and death by exacerbating energy depletion related to futile regeneration of NAD32,33,36. However, considering the pleiotropic actions of PARP, which also includes proinflammatory and death-promoting effects37, the specific contribution of PARP activity to energy depletion and whether the magnitude of the depletion is sufficient to induce cell dysfunction remains unclear38. On the other hand, PARP activity generates PAR, which is cleaved to ADPR by PARG39,40. In turn, ADPR activates TRPM2 channels leading to excessive influx of Ca2+ and other ions that could alter endothelial function26,28,41,42. Therefore, we tested the novel hypothesis that the effects of Aβ on endothelial function are mediated by PARP activity-induced activation of TRPM2 channels. To this end, we first established that Aβ increases PARP activity and PAR production in endothelial cells, and that this effect is associated with DNA damage and requires NADPH-derived ROS, NO and peroxynitrite. Then, we used whole-cell patch clamping to investigate the effect of Aβ on endothelial TRPM2 channel activity. We found that Aβ induces an inward current with the electrophysiological characteristics of TRPM2 currents, which is abolished by TRPM2 inhibition or by TRPM2 knockdown using siRNA. Consistent with an involvement of peroxynitrite, PARP and PARG, TRPM2 currents were suppressed by inhibition of NO or ROS production, and by PARP and PARG inhibitors. Importantly, the current induced by the TRPM2 activator ADPR27,28, delivered intracellularly through the patch pipette, was not affected by ROS scavengers or PARP and PARG inhibitors, ruling out direct effects of these pharmacological agents on the channel. Since endothelial TRPM2 channels are also activated by oxidative stress28, Aβ-induced ROS could activate TRPM2 channels directly. However, this is unlikely because PARP inhibition blocks Aβ-induced TRPM2 currents. Furthermore, PARP inhibition does not affect the ROS production triggered by Aβ, attesting to the fact that PARP activity is downstream of ROS in the signalling events leading to TRPM2 activation. The fact the TRPM2 currents triggered by Aβ are suppressed by inhibition of PARP or PARG also rules out direct effects of Aβ on TRPM2 channels.

We found that TRPM2 channel inhibitors prevent the endothelial dysfunction induced by exogenous Aβ and reverse such dysfunction in tg2576 mice. Similarly, Aβ did not alter endothelial function in TRPM2-null mice, providing nonpharmacological evidence of involvement of TRPM2 in the cerebrovascular effects of the peptide. These findings provide evidence that the TRPM2 channel activation observed in endothelial cultures is reflected in disturbances of endothelial cell regulation in vivo. Since some of the effects of TRPM2 channels are sex-specific43, it would be of interest to investigate whether there are differences in the involvement of these channels in Aβ-induced vascular dysfunction in male and female mice. Interestingly, TRPM2 inhibition or genetic deletion not only improved endothelial-dependent responses but also restored the increase in CBF induced by neural activity. This finding is not surprising considering the emerging role of endothelial cells in the full expression of the increase in CBF evoked by neural activity44. The mechanisms by which TRPM2 channels contribute to neurovascular coupling dysfunction remain to be established. In addition to vascular cells, involvement of TRPM2 on brain cells cannot be ruled out. Irrespective of the effect on functional hyperaemia, however, the in vivo findings corroborate the in vitro evidence linking Aβ to TRPM2 activation and suggest for the first time an involvement of TRPM2 in the endothelial vasomotor dysfunction induced by Aβ.

Our data, collectively, suggest the following hypothetical sequence of events in the endothelial dysfunction induced by Aβ (Fig. 9). Activation of innate immunity receptors, that is, CD36 (ref. 21) or RAGE45, by Aβ leads to production of the ROS superoxide by NADPH oxidase. Superoxide reacts with NO derived from eNOS baseline activity in endothelial cells to form PN, which, in turn, induces DNA damage resulting in PARP activation and PAR formation. ADPR, generated by PARG cleavage of PAR, may then interact with the Nudix domain of TRPM2 opening the channel. However, how does TRPM2 channel activity lead to endothelial dysfunction? We found that the activation of TRPM2 channels by Aβ induces large and sustained increases in endothelial Ca2+. Similar Ca2+ increases were previously observed with H2O2-dependent activation of endothelial TRPM2 channels, leading to increases in endothelial permeability or apoptosis28,29. Furthermore, in microglia TRPM2 activation triggers sustained elevations in intracellular Ca2+ leading to signalling dysfunction46,47. Other ions, such as Na+, entering the cells through TRPM2 channels could also participate in the dysfunction26. It is therefore likely that the mechanisms by which Aβ-induced oxidative–nitrosative stress interferes with endothelial function involve TRPM2-dependent alterations in ionic homeostasis, resulting in suppression of endothelium-dependent vasoactivity. However, the elucidation of the specific pathways involved in the dysfunction downstream of Ca2+ will require additional investigations.

Aβ1–40 (Aβ) activates the innate immunity receptor CD36 leading to production of superoxide via NADPH oxidase. Superoxide reacts with NO, made continuously in endothelial cells, to form peroxynitrite (PN). PN induces DNA damage, which, in turn, activates PARP. ADPR formation by PARG cleavage of PAR activates the Nudix (Nu) domain of TRPM2 leading to massive increases in intracellular Ca2+, which induce endothelial dysfunction. However, the involvement of other TRPM2-permeable anions, such as Na+, cannot be ruled out. In a multicellular context, for example, in vivo, PN, a diffusible agent, could also be produced by other vascular cells, and diffuse into endothelial cells to activate this pathway.

Increasing evidence indicates that AD is a multifactorial disease with multiple pathogenic components48, among which, vascular factors play a prominent role4,5. Not only soluble and oligomeric Aβ impair cerebrovascular function4,5, but Aβ deposits in cerebral blood vessels (cerebral amyloid angiopathy) are present in virtually all patients with advanced AD, and are extremely harmful to cerebral arterioles5,22. These deleterious cerebrovascular effects may contribute to the cognitive deficits by reducing cerebral perfusion and promoting ischaemic brain injury49,50,51. Furthermore, impairment of cerebrovascular vasomotor reactivity may accelerate brain Aβ accumulation by preventing its perivascular and transvascular clearance4. Therefore, it has become imperative to elucidate the mechanisms by which Aβ alters vascular function and, based on these mechanisms, to develop new therapeutic approaches. DNA damage and PARP activation, in the long run, may also promote irreversible structural damage to cerebral vessels4,5,52 by inducing endothelial cell apoptosis through well-established caspase-independent pathways involving AIF53. Our data indicate that TRPM2 may be an attractive therapeutic target for the harmful vascular effects of Aβ. TRP inhibitors are being developed for several neuropsychiatric diseases54 and their use in AD patients may help to counteract the vascular component of the pathogenic process.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the cerebrovascular dysfunction induced by exogenous Aβ or in APP mice requires PARP activity triggered by oxidative–nitrosative stress. The dysfunction depends on activation of TRPM2 channels in cerebral endothelial cells resulting in increases in intracellular Ca2+. The findings shed new light on the downstream mechanisms by which Aβ-induced oxidative–nitrosative stress leads to cerebrovascular dysfunction and raises the possibility that endothelial TRPM2 channels are a putative therapeutic target to counteract the deleterious cerebrovascular effects of Aβ.

Methods

Mice

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Cornell Medical College. Experiments were conducted in C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratories), in mice lacking PARP-1 (The Jackson Laboratories) or Nox2, bred on a C56BL/6J background55,56, and in transgenic mice overexpressing the Swedish mutation of APP (tg2576)17. TRPM2-null mice57 and WT controls were generously provided by Drs Herson and Traystman. All mice were male and 3- to 4-month-old. Age-matched nontransgenic littermates served as controls. Mice were randomly assigned to the experimental groups and experiments were performed in a blinded manner.

General surgical procedures and CBF monitoring

As described in detail previously, mice were anaesthetised with isoflurane (1–2%), followed by urethane (750 mg kg−1; intraperitoneally (i.p.)) and α-chloralose (50 mg kg−1; i.p.). A femoral artery was cannulated for recording of arterial pressure and monitoring of blood gasses. Rectal temperature was monitored and controlled. For CBF monitoring, a small opening was drilled in the parietal bone, the dura was removed and the site was superfused with a modified Ringer solution (37 °C; pH 7.3–7.4)17,18,21,22,24,25. Relative CBF was continuously monitored at the site of superfusion with a laser-Doppler flow probe (Vasamedic).

Experimental protocol for CBF experiments

CBF recordings were started after arterial pressure and blood gases were in a steady state (Supplementary Tables 1–5). All pharmacological agents studied were dissolved in Ringer’s solution, unless otherwise indicated. To study the increase in CBF produced by somatosensory activation, the whiskers were activated by side-to-side deflection for 60 s. The endothelium-dependent vasodilators acetylcholine (10 μM; Sigma) was topically superfused for 3–5 min, and the resulting change in CBF was monitored. CBF responses to the NO donor SNAP (50 μM; Sigma) or the smooth muscle relaxant adenosine (400 μM; Sigma) were also tested21,22,24,25. Hypercapnia (PCO2 to 50–60 mm Hg) was induced by introducing 5% (vol/vol) CO2 in the circuit of ventilator, and the resulting CBF increase was recorded22. CBF responses were tested before and after neocortical superfusion with Aβ1–40 (5 μM) for 30–45 min, freshly solubilized in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) to avoid subsequent peptide aggregation18,31. The final concentration of DMSO (<0.2%) had no cerebrovascular effects31. The Aβ1–40 concentrations were selected based on previous dose–response studies58. We have previously demonstrated that this model of Aβ1–40 application alters endothelial function in arterioles in the fields of superfusion and reproduces in full the cerebrovascular dysfunction observed in Tg2576 mice18,58. In some studies, the effect of Aβ was examined before and 30 min after superfusion with Ringer’s solution containing the peroxynitrite scavenger UA (100 μM; Cayman)59, the peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst 5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato Iron (III), Chloride (FeTPPS; 20 μM; EMD Millipore)59, its inactive version TPPS (20 μM; EMD Millipore)59, the PARP inhibitor PJ34 (3 μM; Sigma)60,61 or the TRPM2 channel inhibitors 2-APB (2-APB; 40 μM; Sigma) or N-(p-Amylcinnamoyl)anthranilic acid (ACA; 20 μM; Sigma). Drugs were tested at concentrations previously established to be relatively selective in this or similar models59,60,62,63.

3-NT and CD31 immunohistochemistry

As described in detail elsewhere59, mice were deeply anaesthetised with 5% isoflurane and perfused transcardiacally with saline. Brains were removed and frozen, and brain sections (thickness: 14 μm) were cut through the somatosensory cortex underlying the cranial window (0.38 to −1.94 mm from Bregma) using a cryostat and collected at 100-μm intervals. To assure uniformity of the immunolabel, sections from controls and treatment groups were processed at the same time and under the same condition. Sections were fixed in ethanol and incubated with rabbit anti-mouse 3-NT (1:200; EMD Millipore) followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200; Molecular Probes). For simultaneous visualization of 3-NT and the endothelial marker CD31, sections were incubated with a rat anti-mouse CD31 monoclonal antibody (1:100; BD Biosciences), followed by a Texas Red goat anti-rat secondary antibody (1:200; Molecular probes). The specificity of the immunolabel was tested by processing sections without the primary antibody or after pre-adsorption with the antigen59. The specificity of the 3-NT immunostain was assessed as previously described64. Brain sections were examined with a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse E800; Nikon) equipped with Texas Red and FITC filter sets. Images were acquired with a computer-controlled digital monochrome camera (Coolsnap; Robert Scientific) using the same fluorescence settings. Cerebrovascular 3-NT immunoreactivity in the different conditions studied (n=5 per group) was quantified using the IPLab software (Scanalytics). After background subtraction of the camera dark current, pixel intensities of 3-NT fluorescent signal over CD31-positive vessels were quantified. Ten randomly selected somatosensory cortex sections per mouse were studied. For each section, fluorescence intensities were divided by the total number of pixels, averaged and expressed as relative fluorescence units.

ROS detection in vivo

As described in detail elsewhere21,24, dihydroethidine (Molecular Probes; 2 μM) was superfused on the somatosensory cortex for 60 min. In some experiments, dihydroethidine was co-applied with UA (100 μM; Calbiochem) or the NOS inhibitor L-NNA (1 mM; Cayman). At the end of the superfusion period, the brain was removed, sectioned (thickness: 20 μm) and processed for detection of ROS-dependent fluorescence as previously described21,24.

Detection of PARP enzymatic activity in vivo

PARP enzymatic activity was detected using a histochemical method adapted from ref. 65. Mice were perfused transcardiacally with heparinized saline (1,000 U ml−1), their brains were removed and the region underlying the cranial window was sectioned (16 μm) using a cryostat. Sections were fixed for 10 min in 95% ethanol at −20 °C, permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100 in 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0, for 15 min and then incubated with a reaction mixture, containing 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 30 μm biotinylated NAD+ in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), for 30 min at 37 °C. After washing in PBS, the sections were treated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (1:100) for 30 min, visualized with a DAB substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), counterstained with Methyl Green and examined under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i). The specificity of the stain was established using the following: (a) brain sections from PARP-1 null mice, (b) WT mice superfused with the PARP inhibitor PJ34 (30 μM) and (c) sections incubated with a biotinylated NAD+-free reaction mixture. Brain sections from mice superfused with bleomycin (200 μg ml−1, Sigma), an agents that induces DNA strand breaks, served as positive control.

Brain endothelial cell cultures and immunocytochemistry

Mouse brain endothelial cells (bEND.3 cells; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured to confluence on coverslips and exposed to Aβ1–40 (300 nM; rPeptide) or scrambled Aβ1–40 (300 nM; rPeptide) for 30 min. This concentration was used because it is comparable to that achieved in the brain of AD patients66. In some studies, cultures were pretreated for 30 min with vehicle or with the ROS scavenger Tempol (1 mM; Sigma) or MnTBAP (30 μM; EMD Millipore), the NOX2 peptide inhibitor gp91ds-tat (1 μM), L-NNA (10 μM), FeTPPS (20 μM) or PJ34 (30 μM). For TRPM2 immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA, washed and processed for double labelling of TRPM2 (1:200; anti-rabbit; Alomone) and CD31 (1:200; anti-rat; BD Biosciences). Cells were then washed and incubated with cy5-conjugated anti-rat IgG (CD31) and FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (TRPM2) secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The specificity of the labelling was established by omitting the primary antibody or by pre-absorption with the antigen. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (Leica).

DNA damage, PARP activity and PAR in endothelial cells

PARP activity was detected as described for the in vivo experiments, except that the reaction product was visualized by FITC-conjugated streptavidin. Cells were fixed for 10 min in 95% ethanol at −20 °C, permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100 in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0) for 15 min and then incubated with a reaction mixture, containing 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 30 μm biotinylated NAD+ in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), for 30 min at 37 °C. PJ34 (30 μM) or a biotinylated NAD+-free reaction mixture was used as a negative control. Then, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated streptavidin (1:100; Invitrogen) to detect incorporated biotin signals, a marker of PARP activity. DNA damage was assessed using the phosphorylated histone variant γH2A.X67 (Ser139; 1:100; anti-rabbit; EMD Millipore). A donkey cyanine dye (Cy)5-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used as a secondary antibody. After washing in PBS, cells were counterstained with the nucleic acid marker To-Pro-3 (1:1,000; Invitrogen). Cells were processed under identical conditions and imaged with the confocal microscope using identical settings. To determine Aβ-induced DNA damage and PARP activity, staining intensity of γH2A.X or PARP activity was quantified using ImageJ and expressed in arbitrary units. To assess PAR formation, cells were fixed for 20 min in 4% PFA at 4 °C and permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 2 min at 4 °C. After blocking with 1% normal donkey serum and washing in PBS, cells were incubated with γH2A.X (Ser139; 1:100; anti-rabbit; EMD Millipore) and PAR antibodies (10 μg ml−1; anti-mouse; Enzo) at 4 °C overnight. Then, cells were incubated with donkey FITC-conjugated anti-mouse (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary IgGs (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch). After washing in PBS, cells were counterstained with the nucleic acid marker To-Pro-3 (1:1,000; Invitrogen). Confocal images were acquired as above. Cells were processed under identical conditions and scanned at the confocal microscope using identical settings. Omission of primary antibody was used as negative control and cells treated with bleomycin (200 μg ml−1) served as positive control. To determine Aβ-induced DNA damage and PAR formation, staining intensity of phospho-γH2A.X or PAR was quantified using ImageJ and expressed in relative fluorescence units.

TRPM2 currents in endothelial cell cultures

TRPM2 channel currents were recorded using whole-cell patch clamp68 in subconfluent endothelial cell cultures. TRPM2 channel opening was induced with Aβ1–40 (300 nM) in the bath solution or intracellular injection of ADP ribose (ADPR; 100 μM)62,63 through the patch pipette. TRPM2 currents were recorded at the holding potential (−50 mV); currents were normalized by the cell capacitance. In some experiments, cells were pretreated for 30 min with 2-APB (30 μM), ACA (20 μM), MnTBAP (100 μM), the NOX2 peptide inhibitor gp91ds-tat (1 μM), L-NNA (10 μM), FeTPPS (20 μM), PJ34 (30 μM) or the PARG inhibitor ADP-HPD (2 μM; EMD Millipore). Drugs were used at concentrations previously established to be relatively specific in similar preparations69. 2-APB also inhibits store-operated Ca2+ entry, but at the concentration used is a relatively specific TRPM2 inhibitor62,63. To complement the results obtained with 2-APB, we also used the mechanistically distinct TRPM2 inhibitor ACA62. Similarly, ADP-HPD was used at a concentration relatively specific for PARG inhibition69.

TRPM2 knockdown in endothelial cell cultures

bEnd cells (1 × 105 cells in a 35-mm dish) were transfected with TRPM2 siRNA (FlexiTube GeneSolution GS28240, Qiagen) or control siRNA (Qiagen) using oligofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The reduction of TRPM2 protein in whole-cell lysates was confirmed with western blot analysis using anti-TRPM2 antibodies (1:200; ant-rabbit; alomone labs). Full scan images of western blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 8. TRPM2 currents or intracellular Ca2+ were assessed 48 h after the transfection.

Assessment of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in endothelial cells

Cytosolic-free Ca2+ was determined using fura-2/AM as indicator (Molecular Probes) in confluent monolayers of endothelial cells grown on poly-L-lysine-coated glass bottom Petri dishes. The bEND.3 cells were loaded with fura-2/AM (5 μM) in artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) composed of (in mmol l−1): 124, NaCl; 26, NaHCO3; 5, KCl; 1, NaH2PO4; 2, MgSO4; 2, CaCl2; 10, glucose; 4.5, lactic acid; oxygenated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.4) for 60 min. The cells then were washed three times with aCSF and incubated in aCSF for an additional 15 min at room temperature. The Petri dish was mounted on a Nikon inverted microscope and images were acquired using a fluorite oil-immersion lens (Nikon CF UV-F X40; numeric aperture 1.3). Aβ1–40 (300 nM) was added directly to the Petri dish. In some experiments, the bEnd.3 cells were pretreated with the TRPM2 inhibitor ACA (20 μM) or 2-APB (30 μM) for 20 min. Fura-2 was alternately excited through narrow band-pass filters (340±7.5 and 380±10 nm). An intensified CCD camera (Retiga ExI) recorded the fluorescence emitted by the indicator (510±40 nm). Fluorescent images were digitized and backgrounds were subtracted. Eight to fourteen endothelial cells were simultaneously recorded in a randomly selected field. At the end of each experiment, cell viability was examined by testing the response to Ca2+ ionophore 4-bromo-A23187 (Calbiochem, CA, USA). Fluorescence measurements were obtained from cell somata, and 340/380 nm ratios were calculated for each pixel by using a standard formula70.

Data analysis

Cells and mice were randomly assigned to treatment with inhibitors or vehicle. Histological and electrophysiological analyses were performed in a blinded manner. Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. Two-group comparisons were analysed by the two-tailed t-test. Multiple comparisons were evaluated by the analysis of variance and Tukey’s test. Differences were considered statistically significant for probability values less than 0.05.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Park, L. et al. The key role of transient receptor potential melastatin-2 channels in amyloid-β-induced neurovascular dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 5:5318 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6318 (2014).

References

James, B. D. et al. Contribution of Alzheimer disease to mortality in the United States. Neurology 82, 1045–1050 (2014).

Dementia: a public health priority. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, (2012).

Gorelick, P. B. et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 42, 2672–2713 (2011).

Zlokovic, B. V. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and other disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 723–738 (2011).

Iadecola, C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 80, 844–866 (2013).

Yaffe, K. et al. Early adult to midlife cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive function. Circulation 129, 1560–1567 (2014).

Purnell, C., Gao, S., Callahan, C. M. & Hendrie, H. C. Cardiovascular risk factors and incident Alzheimer disease: a systematic review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 23, 1–10 (2009).

Snowdon, D. A. et al. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA 277, 813–817 (1997).

Toledo, J. B. et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Centre. Brain 136, 2697–2706 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Global brain hypoperfusion and oxygenation in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 10, 162–170 (2014).

Luckhaus, C. et al. Detection of changed regional cerebral blood flow in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's dementia by perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 40, 495–503 (2008).

McDade, E. et al. Cerebral perfusion alterations and cerebral amyloid in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology 83, 710–717 (2014).

Dede, D. S. et al. Assessment of endothelial function in Alzheimer's disease: is Alzheimer's disease a vascular disease? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 55, 1613–1617 (2007).

Deschaintre, Y., Richard, F., Leys, D. & Pasquier, F. Treatment of vascular risk factors is associated with slower decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 73, 674–680 (2009).

Larson, E. B., Yaffe, K. & Langa, K. M. New insights into the dementia epidemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 2275–2277 (2013).

Mucke, L. & Selkoe, D. J. Neurotoxicity of Amyloid beta-Protein: Synaptic and Network Dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a006338 (2012).

Iadecola, C. et al. SOD1 rescues cerebral endothelial dysfunction in mice overexpressing amyloid precursor protein. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 157–161 (1999).

Niwa, K. et al. Abeta 1-40-related reduction in functional hyperemia in mouse neocortex during somatosensory activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9735–9740 (2000).

Tong, X. K., Nicolakakis, N., Kocharyan, A. & Hamel, E. Vascular remodeling versus amyloid beta-induced oxidative stress in the cerebrovascular dysfunctions associated with Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 25, 11165–11174 (2005).

Zlokovic, B. V. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 57, 178–201 (2008).

Park, L. et al. Scavenger receptor CD36 is essential for the cerebrovascular oxidative stress and neurovascular dysfunction induced by amyloid-beta. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5063–5068 (2011).

Park, L. et al. Innate immunity receptor CD36 promotes cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 3089–3094 (2013).

Deane, R. et al. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat. Med. 9, 907–913 (2003).

Park, L. et al. NADPH-oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species mediate the cerebrovascular dysfunction induced by the amyloid beta peptide. J. Neurosci. 25, 1769–1777 (2005).

Park, L. et al. Nox2-derived radicals contribute to neurovascular and behavioral dysfunction in mice overexpressing the amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1347–1352 (2008).

Moccia, F., Berra-Romani, R. & Tanzi, F. Update on vascular endothelial Ca(2+) signalling: a tale of ion channels, pumps and transporters. World J. Biol. Chem. 3, 127–158 (2012).

Eisfeld, J. & Luckhoff, A. Trpm2. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 237–252 (2007).

Hecquet, C. M., Ahmmed, G. U., Vogel, S. M. & Malik, A. B. Role of TRPM2 channel in mediating H2O2-induced Ca2+ entry and endothelial hyperpermeability. Circ. Res. 102, 347–355 (2008).

Hecquet, C. M. et al. Cooperative Interaction of trp melastatin channel transient receptor potential (TRPM2) with its splice variant TRPM2 short variant is essential for endothelial cell apoptosis. Circ. Res. 114, 469–479 (2014).

Perraud, A. L. et al. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature 411, 595–599 (2001).

Park, L. et al. Abeta-induced vascular oxidative stress and attenuation of functional hyperemia in mouse somatosensory cortex. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 24, 334–342 (2004).

Pacher, P., Beckman, J. S. & Liaudet, L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 87, 315–424 (2007).

Schreiber, V., Dantzer, F., Ame, J. C. & de Murcia, G. Poly(ADP-ribose): novel functions for an old molecule. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 517–528 (2006).

Buelow, B., Song, Y. & Scharenberg, A. M. The Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase PARP-1 is required for oxidative stress-induced TRPM2 activation in lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24571–24583 (2008).

Sano, Y. et al. Immunocyte Ca2+ influx system mediated by LTRPC2. Science 293, 1327–1330 (2001).

Szabo, C., Zingarelli, B., O'Connor, M. & Salzman, A. L. DNA strand breakage, activation of poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase, and cellular energy depletion are involved in the cytotoxicity of macrophages and smooth muscle cells exposed to peroxynitrite. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 1753–1758 (1996).

Pacher, P. & Szabo, C. Role of the peroxynitrite-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase pathway in human disease. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 2–13 (2008).

Gassman, N. R., Stefanick, D. F., Kedar, P. S., Horton, J. K. & Wilson, S. H. Hyperactivation of PARP triggers nonhomologous end-joining in repair-deficient mouse fibroblasts. PLoS ONE 7, e49301 (2012).

Blenn, C., Wyrsch, P., Bader, J., Bollhalder, M. & Althaus, F. R. Poly(ADP-ribose)glycohydrolase is an upstream regulator of Ca2+ fluxes in oxidative cell death. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 1455–1466 (2011).

Bonicalzi, M. E., Haince, J. F., Droit, A. & Poirier, G. G. Regulation of poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase: where and when? Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 739–750 (2005).

Fonfria, E. et al. TRPM2 channel opening in response to oxidative stress is dependent on activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 143, 186–192 (2004).

Perraud, A. L. et al. Accumulation of free ADP-ribose from mitochondria mediates oxidative stress-induced gating of TRPM2 cation channels. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6138–6148 (2005).

Shimizu, T. et al. Androgen and PARP-1 regulation of TRPM2 channels after ischemic injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 33, 1549–1555 (2013).

Chen, B. R., Kozberg, M. G., Bouchard, M. B., Shaik, M. A. & Hillman, E. M. A critical role for the vascular endothelium in functional neurovascular coupling in the brain. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3, e000787 (2014).

Deane, R. et al. A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1377–1392 (2012).

Kraft, R. et al. Hydrogen peroxide and ADP-ribose induce TRPM2-mediated calcium influx and cation currents in microglia. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C129–C137 (2004).

Hoffmann, A., Kann, O., Ohlemeyer, C., Hanisch, U. K. & Kettenmann, H. Elevation of basal intracellular calcium as a central element in the activation of brain macrophages (microglia): suppression of receptor-evoked calcium signaling and control of release function. J. Neurosci. 23, 4410–4419 (2003).

Huang, Y. & Mucke, L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 148, 1204–1222 (2012).

Peca, S. et al. Neurovascular decoupling is associated with severity of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 81, 1659–1665 (2013).

Dumas, A. et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging detection of vascular reactivity in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann. Neurol. 72, 76–81 (2012).

Gurol, M. E. et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy burden associated with leukoaraiosis: a positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann. Neurol. 73, 529–536 (2013).

Garwood, C. J. et al. DNA damage response and senescence in endothelial cells of human cerebral cortex and relation to Alzheimer's neuropathology progression: a population-based study in the MRC-CFAS cohort. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol 10.1111/nan.12156 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) binding to apoptosis-inducing factor is critical for PAR polymerase-1-dependent cell death (parthanatos). Sci. Signal 4, ra20 (2011).

Moran, M. M., McAlexander, M. A., Biro, T. & Szallasi, A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 601–620 (2011).

Pollock, J. D. et al. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat. Genet. 9, 202–209 (1995).

Wang, Z. Q. et al. Mice lacking ADPRT and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation develop normally but are susceptible to skin disease. Genes Dev. 9, 509–520 (1995).

Yamamoto, S. et al. TRPM2-mediated Ca2+influx induces chemokine production in monocytes that aggravates inflammatory neutrophil infiltration. Nat. Med. 14, 738–747 (2008).

Niwa, K., Carlson, G. A. & Iadecola, C. Exogenous A beta1-40 reproduces cerebrovascular alterations resulting from amyloid precursor protein overexpression in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 20, 1659–1668 (2000).

Girouard, H., Park, L., Anrather, J., Zhou, P. & Iadecola, C. Cerebrovascular nitrosative stress mediates neurovascular and endothelial dysfunction induced by angiotensin II. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 303–309 (2007).

Park, E. M. et al. Interaction between inducible nitric oxide synthase and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in focal ischemic brain injury. Stroke 35, 2896–2901 (2004).

Soriano, F. G. et al. Diabetic endothelial dysfunction: the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation. Nat. Med. 7, 108–113 (2001).

Togashi, K., Inada, H. & Tominaga, M. Inhibition of the transient receptor potential cation channel TRPM2 by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB). Br. J. Pharmacol. 153, 1324–1330 (2008).

Toth, B. & Csanady, L. Identification of direct and indirect effectors of the transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30091–30102 (2010).

Forster, C., Clark, H. B., Ross, M. E. & Iadecola, C. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human cerebral infarcts. Acta Neuropathol. 97, 215–220 (1999).

Bakondi, E. et al. Detection of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in oxidatively stressed cells and tissues using biotinylated NAD substrate. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50, 91–98 (2002).

Roher, A. E. et al. Amyloid beta peptides in human plasma and tissues and their significance for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 5, 18–29 (2009).

Bonner, W. M. et al. GammaH2AX and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 957–967 (2008).

Wang, G. et al. COX-1-derived PGE2 and PGE2 type 1 receptors are vital for angiotensin II-induced formation of reactive oxygen species and Ca(2+) influx in the subfornical organ. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 305, H1451–H1461 (2013).

Ramsinghani, S. et al. Syntheses of photoactive analogues of adenosine diphosphate (hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidinediol and photoaffinity labeling of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. Biochemistry 37, 7801–7812 (1998).

Kawano, T. et al. Prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptors: downstream effectors of COX-2 neurotoxicity. Nat. Med. 12, 225–229 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants NS37853 (C.I.) and by the American Heart Association Grant 09SDG2060701 (L.P.). We are grateful to Dr Yasuo Mori (Kyoto University) for allowing us to use TRPM2-null mice under a material transfer agreement and to Drs Paco Herson and Richard Traystman (University of Colorado) for providing the mice. The generous support of the Feil Family Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P., G.W. and C.I. designed the experiments; L.P., G.W., J.M., H.G., P.Z. and J.A. performed experiments; L.P., G.W., J.M., H.G., P.Z., J.A. and C.I. analysed data; L.P., G.W. and C.I. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-8 and Supplementary Tables 1-5 (PDF 1059 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Park, L., Wang, G., Moore, J. et al. The key role of transient receptor potential melastatin-2 channels in amyloid-β-induced neurovascular dysfunction. Nat Commun 5, 5318 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6318

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6318

This article is cited by

-

Border-associated macrophages promote cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive impairment through vascular oxidative stress

Molecular Neurodegeneration (2023)

-

Tau induces PSD95–neuronal NOS uncoupling and neurovascular dysfunction independent of neurodegeneration

Nature Neuroscience (2020)

-

Apoε4 disrupts neurovascular regulation and undermines white matter integrity and cognitive function

Nature Communications (2018)

-

Multiple molecular mechanisms form a positive feedback loop driving amyloid β42 peptide-induced neurotoxicity via activation of the TRPM2 channel in hippocampal neurons

Cell Death & Disease (2018)

-

TRPM2: a candidate therapeutic target for treating neurological diseases

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.