Abstract

In the past 10–15 years, recognition and considerable understanding of much of the so-called ‘serrated pathway’ of colorectal neoplasia has emerged, although much remains to be discovered. Key elements appear to be a propensity for the elderly, females more than males, and right colon; precursor lesions with serrations; and frequent BRAF mutations, hypermethylation (particularly involving the MHL1 promoter), and resultant dysfunctional DNA mismatch repair and microsatellite instability (MSI) of the colorectal adenocarcinomas. For the anatomic pathologist, this has created challenges in sometimes having to morphologically subdivide once-comfortable hyperplastic polyps into hyperplastic polyps and ‘sessile serrated adenoma/polyps’ (SSA/Ps), learn to distinguish these from ‘traditional’ serrated adenomas, and learn to recognize biologically progressing forms of SSA/Ps known as ‘sessile serrated adenoma with cytological dysplasia’. The goal of this article is to highlight for the practicing anatomic pathologist the current status of our understanding of serrated colorectal neoplasms from a practical perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

For the pathologist, endoscopist, gastroenterologist, and colorectal surgeon who were practicing before the year 2000, the emergence of the ‘serrated pathway’ of colorectal neoplasia has been a fairly momentous development that has stirred up significant emotions in many (disbelief, anger, mistrust, and fear, among likely many others). These emotions have been so strong because a bedrock dogma in medicine, that hyperplastic polyps (HPPs) of the colon are innocuous, has been shaken.

From a practical perspective, many practices are now routinely testing new colorectal adenocarcinomas by immunohistochemistry and/or microsatellite instability (MSI) PCR for Lynch Syndrome,1 per recommendations of the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) working group from 2009.2 As part of this practice, about 12–15% of colorectal cancers are found to have absent MLH1 and PMS2 immunostaining (associated with MSI) and either BRAF V600 mutation or methylation of the MLH1 promoter (incompatible with Lynch). This group of cancers has a strong association with the serrated colorectal pathway.

A brief overview of our current understanding of the serrated pathway of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is apropos; a recent extensive review of the topic is available.3

At the epidemiologic level, serrated pathway colorectal adenocarcinomas comprise at least 15% of all CRCs, with a greater percentage occurring in the elderly, right colon, and women. At the molecular level, serrated pathway cancers are characterized by excessive methylation (CPG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP)), propensity for BRAF mutations, and MSI. At the endoscopic level, the precursor polyps are flat, somewhat subtle, sometimes ≥1 cm, fold-mimicking polyps which are more common in the right colon; the Rex et al3 article contains multiple examples. At the histopathology level, the precursor polyps are serrated polyps with somewhat subtle differences from HPPs; these are known as ‘sessile serrated adenomas’ or ‘sessile serrated polyps’ (SSA/P).2 Those SSA/Ps that contain foci of overt dysplasia are known as ‘sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with cytological dysplasia’; these are felt to be associated with a high risk for malignant transformation. At the medical management level, the serrated pathway is associated with a tendency for multiple serrated polyps, both hyperplastic and SSA/Ps, that at the extreme end are regarded as ‘serrated polyposis’ (aka ‘hyperplastic polyposis’). There is an increased cancer risk that appears to parallel to some degree the number, size, type, and distribution of serrated polyps3 and is the basis for most follow-up interval recommendations. It should be noted that current follow-up interval recommendations are all hindered by a relative lack of data and are thus provisional; my personal preference is the follow-up intervals recommended by Rex et al3 (Disclaimer—I am a co-author of this—kpb).

The discipline of Pathology is literally the study of disease, the term ‘pathology’ being derived from the Greek words ‘logos’ (meaning study) and ‘pathos’ (meaning suffering or disease). Pathologists have a key role in serrated neoplasia from the obvious angle of correctly classifying the sampled serrated polyps and cancers arising from the serrated pathways but ideally also from the less obvious angle of providing educational guidance about the various aspects of the disease process to the clinicians and laboratorians with whom we interact. The goal of this presentation/manuscript is to keep the practicing pathologist up to date with current thought on the morphological component of our role in the serrated pathway so that we can function optimally in our day-to-day diagnostic work as the ‘disease doctors’. For simplicity sake, this will be done in a question and answer format, providing practical answers for questions commonly asked by practicing anatomic pathologists.

Has a decision been reached on what I should call ‘the-serrated-polyp-that-isn’t-a-hyperplastic-polyp-anymore’?

The term ‘serrated adenoma’ first appeared in 1990 in an article by Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser,4 but it did not catch on in routine practice as the lesion was not tightly defined histologically, the molecular basis was not yet understood, and the clinical significance was not clear. Torlakovic and Snover5 coined the term ‘sessile serrated adenoma’ (SSA) in 1996 and clearly defined the lesion morphologically. However, as the clinical significance was unclear at the time, this term, too, failed to gain much traction initially. Slowly, the significance of SSA became clearer in the early 2000s, significant articles, including Torlakovic and Snover further defining the morphology in 2003,6 Goldstein et al7 linking SSAs to cancer risk, and work from a number of groups linking SSAs to MSI8 and later to BRAF mutations and methylation.9, 10 Although the link to cancers made the use of the word ‘adenoma’ appropriate for SSAs, there was a considerable reluctance on the part of many to use the term ‘sessile serrated adenoma’ as ‘adenoma’ in the colorectum had such a long history in the context of tubular, tubulovillous, and villous adenomas and using the term ‘adenoma’ in the context of serrated lesions was felt to be potentially confusing. Subsequently, a variety of names sprouted up for this polyp, which added to the confusion.

The WHO took on the topic of naming this polyp in 2010, and a compromise name was reached: ‘Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp’.11 As of 2014, it is hopefully widely understood that the terms ‘sessile serrated adenoma’ and ‘sessile serrated polyp’ are synonymous and either can be used alone or in combination. For the remainder of this article, the term ‘sessile serrated adenoma/polyp’ (SSA/P) will be used.

What are the key morphological features that I should use to distinguish between HPP and SSA/P?

The SSA/P was identified as a subgroup that comprised about 20% of what had previously been called HPPs.6 HPPs have in turn been divided into microvesicular (MV HPP) and goblet cell (GC HPP) types.6 Please see the discussion below regarding the issue of distinguishing GC HPP from MV HPP; it is the MV HPP which has many histological and molecular features in common with the SSA/P. A variety of histological features have been used to define SSA from HPP.5, 6, 7 These fall into the general categories of architectural and cytological observations, both of which likely reflect abnormal maturation in the SSA/P. In daily practice, it is generally the architectural features which are more useful, with the cytological observations being helpful in problematic lesions.

The MV HPP has orderly maturation from crypt base to surface, with a zone of hyperchromasia, paucity of mucin, and proliferative activity at the base and abundant mucin with frequent flocculent ‘microvesicular’ mucin in surface cells (Figure 1). The easiest-to-use architectural feature that distinguishes SSA from MV HPP is basal crypt dilatation and lateral spread of crypt bases that can result in crypt bases that commonly resemble boots, anvils, or Viking ships (Figure 2). Other architectural features that are typical of SSA but less specific are excessive serrations, abundant luminal mucin, an almost-always flat growth, and not-infrequent underlying submucosal lipoma. Occasional penetration of the muscularis mucosae (‘pseudoinvasion’) can be seen—this is more common in SSA/P but can be seen in MV HPP. Using the above, most SSA/Ps are fairly obvious although difficult-to-classify serrated polyps are certainly encountered.

Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp (MV HPP). (a) Low magnification view shows the caricature, with relatively hyperchromatic crypt base and epithelial serrations present in the upper crypts. (b) High power view of the crypt base shows little mucin, high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio, and numerous mitotic figures. (c) High power view of the surface shows abundant ‘microvesicular’ mucin.

Two examples of sessile serrated adenomas (SSA/P). (a) This flat 1-cm transverse colon polyp from a 55-year-old woman shows the characteristic deep crypt dilatation of an SSA/P. (b) This 16–20 mm right colon polyp from an 82-year-old woman shows the crypt dilatation and the exaggerated serrations often seen in SSA/P. (c) This 3–4 mm flat sigmoid polyp from a 67-year-old woman shows more exaggerated lateral spread of crypt bases. Note also the abundant mucin in the crypt base epithelium, a feature not present in MV HPPs (as shown in Figure 1b), indicative of the disordered crypt maturation in SSA/Ps.

Cytological features to distinguish SSA/P from MV HPPs are more difficult to apply in daily practice but can be useful in problematic lesions. In MV HPPs, the proliferative zone is predictably basal, with hyperchromasia and mitoses/proliferative activity generally confined to the basal third of the crypt (Figure 1). With SSA/Ps, the proliferative zone is irregular, with some areas showing basal crypt proliferation but other areas showing an upward migration of the proliferative zone into the middle third of the crypts, with a resulting mixture of upwardly and downwardly migrating epithelial cells. The downwardly migrating cells may demonstrate a mature gastric foveolar-type appearance at the base (Figure 2c) as opposed to the hyperchromasia of microvesicular HPPs (Figure 1b). This downward migration may well be what contributes to the lateral spread and dilatation of the crypt bases as these maturing cells have nowhere to go.

Can size or location be used as a surrogate for morphology when attempting to distinguish between MV HPP and SSA/P?

The majority of MV HPPs and SSA/Ps are readily classified based on the architectural features described above, but size and location information can be helpful as well. In the context of serrated polyposis, the mean size of MV HPPs was 3.2 mm (±1.8) vs 4.9 mm (±2.6) for SSA/Ps and about two-thirds of the HPPs were distal and about two-thirds of the SSA/Ps were proximal.12 In our practice, we estimate that about 90% of HPPs are distal and about two-thirds of the SSA/Ps are proximal.

Translating this into daily practice, I recommend using morphology to distinguish between MV HPP and SSA/P (your ratio should be about 80:20) but will admit that it is not unreasonable to use size and location to ‘break ties’ when the morphology is ambiguous. Having a mechanism for knowing what the endoscopist has seen is obviously important. In general, polyps qualifying as MV HPP will be small (<5 mm) and left sided; however, occasionally 6–9-mm examples will be encountered and occasionally right colon MV HPPs will be seen. The MV HPP-like polyp that is >10 mm will almost always have at least focal architectural features that qualify it as an SSA/P (see discussion below regarding minimum criteria for SSA/P). Although SSA/Ps have gained notoriety for being large (>1 cm) and right sided, it is quite common to find small (<5 mm) examples throughout the colon (Figure 2c).

What are the minimum morphological criteria for calling something an SSA/P rather than MV HPP?

There is likely no study that will ever answer this question definitively. It currently remains unanswered whether SSA/Ps arise de novo or represent degeneration of a preexisting HPP. The finding of small ‘pure’ SSA/Ps and the differing distributions for MV HPPs (left predominant) vs SSA/Ps (right dominant) have been used to favor the argument of de novo SSA/Ps. The frequent finding of MV HPP-like areas within large SSA/Ps and the finding that excessive methylation and BRAF mutations are seen frequently in both MV HPPs (at 66–75%) and SSA/Ps (at 85%)12, 13 are arguments that could be used to say that SSA/Ps represent ‘advanced’ forms of MV HPPs. A study group convened at the Cleveland Clinic (which included this author) recommended that one convincing ‘boot shaped’ crypt in a serrated polyp was sufficient for the diagnosis of SSA.3 This was done in recognition that there was a need for some criterion but no hard data exist, that ‘cutoffs’ of 2, 3, 4, etc boot-shaped crypts were going to be equally arbitrary, and that concurrent follow-up recommendations from this group3 factored in polyp size as a hedge against correct subclassification of the polyp. Data to definitively solve this issue will be difficult to obtain.

What is a ‘sessile serrated adenoma with cytological dysplasia’?

This is an underlying SSA/P that has developed a sharply delimited subclone-looking focus of overt cytological dysplasia that resembles the dysplasia seen in usual tubular adenomas of the colorectum.(Figure 3). The name ‘sessile serrated adenoma with cytologic dysplasia’ (‘SSA/P wCD’) was chosen by the WHO11 to reflect that the dysplastic area is arising from an underlying SSA/P and is NOT merely adjacent tubular adenoma and sessile polyp. Multiple lines of evidence support this contention. Morphologically, one often observes cup-shaped areas of dysplasia surrounded by SSA/P. Immunohistochemically, the dysplasia nearly always shows loss of MLH1 immunoreactivity, whereas this is not a feature of the classic adenoma-carcinoma sequence. At the molecular level, the dysplastic focus retains the BRAF mutations seen in the adjacent SSA/P.

Sessile serrated adenoma with cytological dysplasia—72-year-old woman, right colon. (a) A typical SSA/P is present, with characteristic deep crypt lateral spread. (b) Focally, there is a sharp clonal-type demarcation with a component that resembles a tubular adenoma morphologically, felt to represent a sub-clone arising in the SSA/P. (c) The subclone is not simply an adjacent tubular adenoma as it has lost hMLH1 immunoreactivity, reflective of the dysplastic area arising through hMLH1 promoter methylation—usual tubular adenomas would retain hMLH1 immunoreactivity. The SSA/P component characteristically retains hMLH1 reactivity. (d) The presence of BRAF immunoreactivity, reflective of BRAF V600E mutation, in both the SSA/P and the dysplastic subclone, is further evidence that the dysplastic subclone is not just an adjacent tubular adenoma as tubular adenomas would not demonstrate BRAF mutations.

Early, SSA/P wCD will not look any different than usual SSA/Ps to the endoscopist, but as they enlarge (which may happen briskly) they will become more endoscopically protuberant. This presumed subclone of dysplasia is felt to serve as a marker that the SSA is close to acquiring the ability to invade (adenocarcinoma). The observation that the subclonal dysplasia is frequently seen in SSAs with malignant degeneration has been the major fuel for this argument, and the relative infrequency with which one encounters SSA with cytological dysplasia in the absence of cancer in polypectomy specimens has fueled the argument that these lesions may progress rapidly to cancer.

Because of the concern for potentially rapid acquisition of the capability to invade, it is recommended that the endoscopist be certain these lesions have been completely removed and, once removed, consideration for early (1–3 years) follow-up surveillance endoscopy be employed.3

What is a ‘traditional’ serrated adenoma and how does it fit into the serrated neoplasia scheme?

The ‘traditional’ serrated adenoma (TSA) has been a source of some ongoing controversy, likely related in some part to confusing terminology and definitions and variable application of these definitions into daily practice. We cannot hope to solve these controversies here, but we will review what is known about these.

Despite TSA sharing two-thirds of its name with SSA, the lesions are distinctively different histologically, endoscopically, and pathogenetically—they are NOT felt to be part of the serrated pathway of colorectal neoplasia that involves SSA/P, SSA/P wCD, MLH1 hypermethylation, and BRAF mutations described above.3

Endoscopically, TSAs are relatively rare (<1% of all colon polyps), left-side predominant, sessile but protuberant and easily recognized, and range from very small to (often) >1 cm. Histologically (Figure 4), they do not have the base-to-surface maturation seen in MV HPP and SSA/P, in contrast being relatively (but not entirely) uniform throughout.14 Also, they frequently demonstrate a significant villous component (‘filiform’), which is not a feature of SSA/P. Cytologically, cytoplasm is typically abundant and eosinophilic with interspersed goblet cells that in some cases can be predominant. Nuclei are central or basal, moderately hyperchromatic, uniform, and often thin (‘pencillate’). Proliferative activity is in general low with infrequent mitoses. A more recently recognized feature of TSA is the ‘ectopic crypt focus’, representing abortive attempts at new crypt base formation high in the polyp, well away from the muscularis mucosae. The TSA is most likely to be misclassified as a villous adenoma.

Traditional serrated adenoma (TSA). (a) On low power, they typically have a villiform appearance with conspicuous serrations. (b) Many of the serrations are associated with ‘ectopic crypts’, which are felt to represent abortive attempts at forming new crypt bases throughout the polyp. Goblet cells are present in variable numbers as shown here. (c) Ki67 immunostaining tends to be strongest in the ectopic crypt bases. (d) Hyperchromatic pencillate-shaped nuclei are present; the cytoplasm is often intensely eosinophilic as shown here, although mucin may be present as well (as shown in panel b).

The niche of TSAs remains uncertain. Foci resembling TSA can be seen in SSA/Ps—the significance in this context is uncertain. Foci resembling classing tubular adenoma-like dysplasia can also be seen in TSAs—the significance is uncertain as well. Studies have shown variable results for (mutually exclusive) KRAS and BRAF V-600 mutation, but clearly they have much lower BRAF mutation frequency than SSA/Ps, and KRAS mutations are not a feature of the serrated pathway associated with SSA/Ps. Until such time as these lesions are fully understood, managing these similar to tubular adenomas of similar size is probably reasonable as they do portend some malignant risk; Rex et al3 lump these with SSA/Ps for follow-up purposes.

What is a ‘goblet cell’ HPP, and how does it fit into the serrated neoplasia scheme?

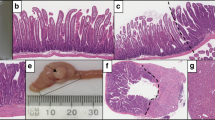

Although goblet cell HPP (GC HPP) shares half of its name with MV HPP, the two polyps appear to be unrelated. Serrations are minimal to absent in GC HPPs, and the proliferative zone is inconspicuous as opposed to the zone of basal hyperchromasia typical of MV HPP.6 The mucin in GC HPP is abundant and exclusively in the form of goblet cells, in contrast to the surface cells with soft ‘microvesicular’ mucin in MV HPPs6 (Figure 5).

Goblet cell type hyperplastic polyp (GC HPP). Mostly left sided and usually small, they can be histologically subtle as serrations may be minimal (as shown here) to non-existent. Elongated crypts with a dense population of goblet cells from crypt base to surface but little mitotic activity are typical features.

GC HPPs do not appear to have a role in the serrated pathway involving SSA/Ps. In contrast to MV HPPs, where BRAF mutations are seen in 66–75% of cases, BRAF mutations are infrequent, being seen in 0% of GC HPPs seen in serrated polyposis patients in one study.12 KRAS mutations are seen in some GC HPPs; however, a role for GC HPPs as cancer precursors has not been shown to date. For practical purposes, GC HPPs and MV HPPs are generally lumped together as simply ‘HPPs’ in most practices today. This is probably reasonable, with the exception that they should not be used to contribute to the syndrome with multiple serrated polyps known as ‘serrated polyposis’, which is composed of a mixture of MV HPPs and SSA/Ps. (see below).

What is ‘serrated polyposis’, and how does it relate to ‘hyperplastic polyposis’?

‘Serrated polyposis syndrome’ (SPS) is the new name endorsed by the WHO for what was previously known as ‘hyperplastic polyposis’.11 The name change reflects the understanding that the polyps that comprise this syndrome represent a mixture of SSA/Ps and MV HPPs rather than only MV HPPs. The updated 2010 WHO criteria that define SPS are any one of the following: (1) at least five serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon with ≥2 of these being >10 mm; (2) any number of serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon in an individual who has a first-degree relative with SPS; or (3) >20 serrated polyps of any size, distributed throughout the colon. (3;11) It appears that SPS is a reflection of generalized colonic hypermethylation as even the normal intervening mucosa has an increased degree of methylation.15 Given the methylation link, the presence of GC HPPs should probably not contribute to the polyp count for SPS given their lack of association with hypermethylation. There remains considerable phenotypic diversity within SPS, and it is unclear whether it is a pure entity as no germline mutation has been associated with it to date and most cases are sporadic.3 There is a clear increase in cancer risk with SPS. Management of this cancer risk ideally consists of every 1–3-year colonoscopy with complete endoscopic removal of all polyps, but if the polyps become unmanageable extended right hemicolectomy or subtotal colectomy become reasonable options.3, 11

Summary

The serrated pathway of colorectal neoplasia has emerged as a significant contributor to the development of CRCs, albeit a minority. Although much has been learned about this pathway (largely in the past 10–12 years), undoubtedly much is yet to be discovered in terms of chemoprevention, optimal surveillance strategies, and chemotherapies for CRC arising from the serrated/CIMP pathway. For practicing pathologists in 2014, opportunities for impacting patient care include properly categorizing the various serrated polyps morphologically, identifying CRC that have originated from this pathway, and fulfilling our role as the ’disease doctors’ in helping clinicians understand the significance of the various polyps we are diagnosing and guide them in the appropriate management of these patients.

References

Burt RW . Diagnosing Lynch syndrome: more light at the end of the tunnel. Cancer Prev Res 2013;5:507–510.

Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: genetic testing strategies in newly diagnosed individuals with colorectal cancer aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome in relatives. Genetic Med 2009;11:35–41.

Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendation from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1315–1329.

Longacre TA, Fenoglio-Preiser CM . Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:524–537.

Torlakovic EE, Snover DC . Serrated adenomatous polyposis in humans. Gastroenterology 1996;110:748–755.

Torlakovic EE, Skovlund E, Snover DC et al. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:65–81.

Goldstein NS, Bhanot P, Odish E et al. Hyperplastic-like polyps that preceded microsatellite-unstable adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 2003;119:778–796.

Iino H, Jass JR, Simms LA et al. DNA microsatellite instability in hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps: a mild mutator pathway for colorectal cancer? J Clin Pathol 1999;52:5–9.

Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL et al. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut 2004;53:1137–1144.

O’Brien MJ, Yang S, Mack C et al. Comparison of microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation phenotype, BRAF and KRAS status in serrated polyps and traditional adenomas indicates separate pathways to distinct colorectal carcinoma end points. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:1491–1501.

Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW et al. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis In: (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2010, pp 160–165.

Rosty C, Buchanan DD, Walsh MD et al. Phenotype and polyp landscape in serrated polyposis syndrome: a series of 100 patients from genetics clinics. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:876–882.

Rosty C, Parry S, Young JP . Serrated polyposis: an enigmatic model of colorectal cancer predisposition. Pathology Res Int 2011;2011:1157073.

Torlakovic EE, Gomez JD, Driman DK et al. Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) vs traditional serrated adenoma (TSA). Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:21–29.

Minoo P, Baker K, Goswami R et al. Extensive DNA methylation in normal colorectal mucosa in hyperplastic polyposis. Gut 2006;55:1467–1474.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Sarah Fleming and Joseph Hodapp for assistance in preparing figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Batts, K. The pathology of serrated colorectal neoplasia: practical answers for common questions. Mod Pathol 28 (Suppl 1), S80–S87 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.130

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.130

This article is cited by

-

Nonconventional dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal carcinoma: a multicenter clinicopathologic study

Modern Pathology (2020)

-

Could Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis cause Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis…and colorectal cancer?

Infectious Agents and Cancer (2018)

-

Serrated Polyps of Colon and Rectum: a Clinicopathologic Review

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2017)