Abstract

Primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma, a provisional entity in the 2005 WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas, is not well characterized. Fifteen cases meeting the definition of this entity were identified. Fourteen represented solitary lesions on the head/neck (n=9), upper extremity (n=4), or trunk (n=1). One patient presented with multiple lesions on the trunk and extremities. Histologically, the infiltrate showed a nodular pattern in the dermis and subcutis without epidermotropism, and had a polymorphous composition with a predominance of small to medium-sized CD4-positive T cells. Most cases showed normal T-cell antigen expression; diminished/absent expression of CD7 was seen in three cases and CD2 expression was absent in one case. All cases showed a notable reactive infiltrate including frequent B cells, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Clonal TCR gene rearrangements were detected in each case. No clonal Ig gene rearrangements were detected. Out of the 11 patients with follow-up, none showed systemic disease. The majority resolved without relapse, one without treatment, four with excision, and four with radiation therapy. One patient developed local recurrence. The patient with multiple lesions had disease progression despite chemotherapy and stem cell transplant. These cases highlight the polymorphous histology and prominent reactive B-cell component of this entity. Diagnosis requires molecular genetic analysis, as prominent cytologic atypia and immunophenotypic aberrancy are rare. The differential diagnosis includes reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, mycosis fungoides and cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. In patients with isolated cutaneous lesions, the indolent behavior of this rare T-cell neoplasm should be recognized to avoid unnecessary treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas represent a heterogeneous group of diseases. Mycosis fungoides and primary cutaneous CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders account for the vast majority (>90%) of cases.1 Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas outside these two groups were recognized and included under the categories of T-immunoblastic, medium-sized/large cell pleomorphic, and small cell pleomorphic in the updated Kiel classification of lymphomas.2 The first two categories were associated with a very poor prognosis, and the last category generally showed a favorable prognosis.3, 4, 5 Subsequent studies have redefined these categories in an attempt to better divide cutaneous T-cell lymphomas into clinically uniform groups.

Further analysis of prognostic data in patients with primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma suggested that a predominance of medium-sized cells was associated with a favorable prognosis similar to that observed in cases of the small cell pleomorphic type, which contrasted with the poor prognosis associated with the large cell pleomorphic type.4 Beljaards et al4 proposed that small to medium-sized pleomorphic types should be distinguished from large pleomorphic types of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma based on the presence of less than 30% large pleomorphic tumor cells. This criterion was integrated into the definition of pleomorphic small/medium-sized cutaneous T-cell lymphoma when it was recognized as a provisional entity in the 1997 EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas.6

When applying the EORTC classification, approximately 3% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas in the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group registry between 1986 and 1994 fell into the category of pleomorphic small/medium-sized cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.6 The 5-year survival of these patients ranged from 62 to 82%, based on several small series.6, 7, 8 In another attempt to eliminate heterogeneity from this group, Bekkenk et al9 evaluated prognostic factors in a group of 82 patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified, presenting in the skin. Similar to the other studies, they found that patients with primary cutaneous small or medium-sized T-cell lymphomas had a significantly better prognosis compared to those with cutaneous CD30-negative large T-cell lymphoma as well as those presenting with concurrent extracutaneous disease. However, the improved survival appeared to correlate with a CD4-positive, CD8-negative phenotype, and localized skin lesions.9 Based on this data, the 2005 WHO-EORTC classification restricted the provisional category to cases with a CD4-positive T-cell phenotype.1

As the definition of the provisional entity of primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma (CSMTCL) has evolved, the few studies reporting the clinicopathologic features have included a heterogeneous group of diseases,3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 making it difficult to draw conclusions about diagnostic features. This study represents the first description of the clinicopathologic features of CSMTCL in a uniform set of cases meeting the updated definition of the 2005 WHO-EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas.

Materials and methods

Mayo Clinic consultation files were retrospectively searched for cases that met the criteria for CSMTCL, as defined by the WHO-EORTC classification. The search was limited to the last 2 years, so that all the cases would have been uniformly evaluated for T-cell clonality by the same validated PCR method. Additional cases were identified prospectively over a 2-year period in the consultation practice. Patients with a history of plaques or patches characteristic of mycosis fungoides were excluded. Cases of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia without demonstrable clonality were also excluded.

In each case, paraffin immunohistochemical studies using standard methods were performed with antibodies directed against CD2 (Novocastra/Vision BioSystems, Norwell, MA, USA, clone AB75), CD3 (Novocastra/Vision BioSystems, clone PS1), CD4 (Novocastra/Vision BioSystems, clone 4B12), CD5 (Novocastra/Vision BioSystems, clone 4C7), CD7 (Novocastra/Vision BioSystems, clone CD7-272), CD8 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA, clone C8/144B), CD10 (Novocastra/Vision BioSystems, clone 56C6), CD20 (Dako, clone L26), CD30 (Dako, clone BerH2), β-F1 (Endogen/Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA, clone 8A3) TIA-1 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA, clone TIA-1), bcl-6 (Dako, clone PG-B6p), Ki-67 (Dako, clone MIB-1), and κ- and λ-immunoglobulin (Ig) light chains (Dako, polyclonal). All immunostaining was performed on a Dako automated platform. Heat induced epitope retrieval was used for all antibody protocols except β-F1, in which the pretreatment included proteolytic enzyme.

In each case, PCR analysis of Ig heavy and κ-light-chain genes10 and T-cell receptor (TCR) γ-chain genes (in house developed and validated assay; unpublished method) was performed and interpreted according to established methods in the clinical molecular hematology laboratory at Mayo Clinic. For TCR PCR, peaks in the Vγ 1, 3, or 4 ranges with amplitude at least two times greater than the Vγ 1 background were considered positive. For the Vγ 2 range, peaks with amplitude at least three times greater the Vγ 1 background were considered positive. Samples showing two or more discrete peaks were considered oligoclonal. In four cases with available frozen tissue, Southern blot analysis was performed using EcoRI restriction digest and two separate probes for the TCR β-gene, one to the first and one to the second joining regions, according to previously described techniques.11 Clinical staging information and follow-up was obtained when possible from referring pathologists or oncologists.

The Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Fifteen cases were identified that met diagnostic criteria for CSMTCL (Table 1). All the cases were from a 4-year period, with six identified retrospectively and nine prospectively in the consultation practice. The patients included seven male subjects and eight female subjects, ranging in age from 14 to 74 years (average 56 years). Fourteen patients presented with solitary cutaneous lesions on the head and neck (9 of 15; 60%), upper extremity (4 of 15; 27%), or trunk (1 of 15; 7%). These solitary lesions ranged in size from 1 to 2.5 cm in diameter. A single patient presented with multiple lesions on the trunk and extremities; the largest was present on the forearm and grew to 14 cm over 1 year. Many of the lesions developed rapidly over weeks to months, with two patients reporting waxing and waning of the lesion without therapy. The clinical impression of the lesions included cutaneous cyst, furuncle, and dermatofibroma.

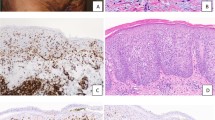

Histologically, all the cases shared similar features. The infiltrate lacked epidermotropism and involved the entire dermal thickness in an interstitial or periadnexal pattern, often with nodular extension into the subcutis (Figure 1a–d). There was a polymorphous composition with predominance of small to medium sized pleomorphic cells with mild to moderate cytologic atypia. The atypical cells often included elongated, hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli, and in other cases showed irregular nuclear membranes (Figure 1e–h). Variable numbers of scattered large lymphoid cells were present, comprising less than 30% of the infiltrate. A consistent feature in all cases was a notable reactive infiltrate including frequent small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes (Figure 1e–h). In one case the infiltrate also contained scattered eosinophils (case 1), and in another rare neutrophils (case 14).

Histologic appearance of primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma. (a and b) Low-power view of cases 9 (a) and 14 (b) showing partly diffuse, partly nodular dense lympho-histiocytic infiltrate occupying full thickness of the dermis. (Cases 9 (a) and 14 (b), hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 20). (c) The lymphoid infiltrate is centered on skin appendages but no epidermotropism is seen. (Case 12, hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 100). (d) The lymphoid infiltrate invariably involves the subcutaneous adipose tissue. (Case 14, hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 100). (e) High-power view shows the polymorphic nature of the infiltrate comprising lymphoid cells, histiocytes and plasma cells. (Case 14, hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 400). (f) High-power view of the only case with refractory disease showing a comparatively monomorphic infiltrate of atypical lymphoid cells. (Case 11, hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 400). (g and h) Careful examination highlights lymphoid cells with atypical nuclear features in most cases. These are always intermixed with reactive cells, which include histiocytes and plasma cells. (Case 11 (g) and Case 9 (h), hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 1000).

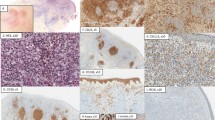

The immunophenotypic findings in CSMTCL are illustrated in Figure 2. In accordance with the definition provided by the WHO-EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas, the predominant population in these cases had a CD3-positive, CD4-positive, CD8-negative, and CD30-negative phenotype. In the majority of the cases, this CD4-positive T-cell population showed normal expression of pan T-cell antigens CD2, CD3, CD5, and CD7, and were of the α/β T-cell subset (positive using antibodies directed against β-F1). Diminished/absent expression of CD7 was seen in three cases (cases 1, 10, and 13), and diminished expression of CD2 was seen in case 8. Only one case showed definite phenotypic aberrancy with complete loss of CD2 expression (case 11). This case was also clinically distinct with multiple cutaneous lesions. The proliferation fraction was low to intermediate (10–30% of cells) in the three cases that were tested (cases 4, 9, and 10) with the Ki-67 immunostain. Intermixed reactive cells were frequent, including CD8-positive and TIA-1-positive cytotoxic T cells that comprised 5–10% of the infiltrate. The B-cell component comprised between 10 and 40% of the cells in the infiltrate, and consisted of scattered large B immunoblasts and nodules of small lymphocytes resembling primary follicles. Secondary lymphoid follicles were not present, and the B cells lacked expression of the follicle center cell-associated antigens CD10 and bcl-6. Plasma cells and B lymphocytes had a polytypic staining pattern for κ- and λ-light chains as observed by immunohistochemistry.

Immunophenotype of primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma, case 9. (a) The lymphoid infiltrate is mostly composed of CD3-positive T cells extensively infiltrating full thickness of the dermis (immunoperoxidase, original magnification × 40). (b) There is invariably a significant CD20-positive B-cell population that is arranged into ill defined nodules (immunoperoxidase, original magnification × 40). (c) High-power view of CD3 and T-cell receptor β-chain-β F1, (d) staining highlights cytological aypia in a subset of the T cells (immunoperoxidase, original magnification (c) × 400, (d) × 1000). (e–f) The lymphoid infiltrate is overwhelmingly CD4 positive (e), but appears mostly negative for CD8 (f) (immunoperoxidase, original magnification × 400).

Clonal TCR gene rearrangements were detected in each case. In 11 cases the clonal TCR rearrangement was detected by PCR. In the four cases with available frozen tissue, clonal TCR rearrangement was detected both by PCR and Southern blot (Figure 3). No clonal Ig gene rearrangements were detected.

Molecular genetic studies in primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma, case 1. (a) Results of a PCR-based assay using primers for T-cell receptor γ-chain gene, analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. Red arrows indicate clonal peaks. Each color represents fragments amplified by primers corresponding to different exons of the γ-gene: green (exon V9/Vγ2), blue (exons V2 to V8/Vγ1), and black (exon V10/Vγ3). The range corresponding to exon V11/Vγ4 showed no amplification and cannot be seen in this figure. (b) Southern blot analysis of the T-cell receptor genes using probes for Jβ2. Lane 1, DNA extracted from case 1; lane 2, negative control; lane 3, positive control. Red arrows indicate clonal rearrangement bands; black arrows indicate germline bands.

Follow-up was available in 11 patients (range 1–26 months, median 9 months). No patient showed systemic disease by clinical staging. In the majority of patients the lesion resolved without relapse, one without treatment, four with excision, and four with radiation therapy. One patient treated only with excision experienced recurrence at the same site (case 8). The patient with multifocal lesions (case 11) had disease progression, limited to the skin, despite multiple chemotherapy regimens (CHOP, miniBEAM, α-interferon, and ESHAP) and autologous stem cell transplant. She was alive with disease at 26 months.

Discussion

Primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma was included as a provisional entity in the 2005 WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphoma, comprising 2–3% of cutaneous lymphomas in the Dutch and Austrian Cutaneous Lymphoma Group registry between 1986 and 2002.1 Owing to its rarity and the evolution of this category in recent years, clinicopathologic features of this entity are not well established. The current definition describes a cutaneous lymphoma with a predominance of small to medium-sized pleomorphic CD4-positive T cells that lacks clinical features typical of mycosis fungoides.1 Based on this series of cases, CSMTCL does represent a distinct clinicopathologic category, characterized by presentation as a solitary cutaneous nodule usually on the head and neck, polymorphous histology with a prominent reactive B-cell component, and indolent clinical behavior.

The majority of patients in this series (60%) presented with solitary lesions on the head and neck, with other locations including the upper extremities and trunk. The predilection of CSMTCL for these cutaneous sites and presentation as localized disease confirms what has been suggested by the previous reports.5, 12, 13

Very few reports exist that describe the histopathologic features of this disease in detail, and all of the prior published studies predate the definition provided by the WHO-EORTC. All of our cases were characterized by a nodular to diffuse polymorphous infiltrate that invariably extended into the deep dermis and often the subcutaneous tissue. In addition to the small to medium-sized pleomorphic CD4-positive T cells, in every case we noted a prominent intermixed reactive infiltrate consisting of B cells, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Our findings are consistent with the published case reports, although the prominent B-cell component has not always been emphasized. Kim and Vandersteen12 reported a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma involving the face of a 19-year-old man that met the definition of CSMTCL. Similar to our cases, the lymphomatous infiltrate was polymorphous with approximately 20% intermixed B cells. The patient was treated with local radiation therapy that led to complete remission.

Given the polymorphous nature of the infiltrate in CSMTCL, there is substantial histologic overlap with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (cutaneous pseudo-T-cell lymphoma). The differential diagnosis is made more difficult by only mild to moderate cytologic atypia in the lymphocyte population, in some cases to a degree that could occasionally be seen in reactive cutaneous T-cell infiltrates. Furthermore, phenotypic aberrancy was rare, being found in only 1 of 15 cases. These features indicate that confirmation of a clonal TCR gene rearrangement by molecular genetic analysis should be a requirement for diagnosis. Although it is possible that some of our cases may indeed represent cutaneous pseudolymphoma in which an oligoclonal T-cell population yielded misleading molecular genetic results, the confirmation of clonal TCR rearrangements by Southern blot in four of the cases would argue against this idea. Regardless of whether or not the positive PCR result truly reflects a clonal T-cell population, pathologists need to be aware of the consistency of this finding in this clinicopathologic entity.

The prominent B-cell component in these cases also brought cutaneous B-cell lymphomas into the differential diagnosis, particularly extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type, which characteristically has a polymorphous background. Exclusion of MALT lymphoma can be difficult on histologic grounds, and requires immunophenotyping studies to evaluate for B-cell/plasma cell clonality and possibly molecular genetic analysis of Ig genes. All of our cases lacked clonal Ig gene rearrangements by PCR analysis.

Given the important prognostic implications, other cutaneous T-cell lymphomas also need to be excluded before a diagnosis of CSMTCL can be made. The histologic features show overlap with tumor phase mycosis fungoides and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified. In contrast to the band-like infiltrate with epidermotropism characteristic of mycosis fungoides, CSMTCL shows a nodular infiltrate in the deep dermis and subcutis and does not significantly involve the epidermis. Clinical history is necessary to definitively exclude a tumor phase of mycosis fungoides. Cases with greater than 30% large pleomorphic tumor cells should be classified as peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified, according to the definition provided by the WHO-EORTC classification.1 In cases with predominance of small and medium-sized pleomorphic T cells, the distinction from a systemic or primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified is more difficult. Based on the appearance of our cases, features such as a polymorphous infiltrate and a lack of severe cytologic atypia or phenotypic aberrancy would favor CSMTCL. However, clinical correlation and staging studies are always necessary for most accurate classification and management. The one case in our series that showed clinical progression despite chemotherapy was distinct as multiple cutaneous lesions were present and the neoplastic T cells showed aberrant loss of CD2 expression (case 11). Another case that recurred showed diminished CD2 expression (case 8). As suggested in previous studies of CSMTCL, these features may correlate with more aggressive disease, and possibly should exclude these cases from that diagnostic category.9

Studies to date have indicated that CSMTCL has a favorable prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of 60–80% compared to 20% for cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified.1, 6, 7, 8, 9 Using updated criteria for the diagnosis of CSMTCL may further improve the survival rates for this category of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Although our follow-up was limited, in the majority of the patients the lesion resolved with conservative therapy, and none of our patients died of disease. In fact, two of our patients experienced spontaneous, partial, or complete resolution of the cutaneous lesion. This is in agreement with other reports of CSMTCL showing stable disease over many years or spontaneous regression.9, 13

In summary, CSMTCL represents a rare but recognizable clinicopathologic entity, and should be acknowledged as a diagnostic category separate from cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified. Given the histologic and immunophenotypic overlap with benign and malignant cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates, diagnosis requires careful morphologic and immunophenotypic analysis, as well as molecular genetic studies. In patients with solitary lesions limited to the skin, an indolent clinical course can be expected. Recognition of this entity is important to avoid unnecessary treatment for these patients.

References

Willemze R, Jaffe E, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood 2005;105:3768–3785.

Stansfield A, Diebold J, Kapanci Y . Updated Kiel classification for lymphomas. Lancet 1988;i:292–293.

Sterry W, Siebel A, Mielke V . HTLV-1 negative pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma of the skin: the clinicopathologic correlations and natural history of 15 patients. Br J Dermatol 1992;126:456–462.

Beljaards R, Meijer C, van der Putte S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic features and prognostic parameters of 35 cases other than mycosis fungoides and CD30-positive large cell lymphoma. J Pathol 1994;172:53–60.

Friedmann D, Wechsler J, Delfau M-H, et al. Primary cutaneous pleomorphic small T-cell lymphoma: a review of 11 cases. Arch Dermatol 1995;131:1009–1015.

Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Blood 1997;90:354–371.

Grange F, Hedelin G, Joly P, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and the Sezary syndrome. Blood 1999;93:3637–3642.

Fink-Puches R, Zenahlik P, Back B, et al. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: applicability of current classification schemes (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, World Health Organization) based on clincopathologic features observed in a large group of patients. Blood 2002;99:800–805.

Bekkenk M, Vermeer M, Jansen P, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas unspecified presenting in the skin: analysis of prognostic factors in a group of 82 patients. Blood 2003;102:2213–2219.

McClure R, Kaur P, Pagel E, et al. Validation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement detection by PCR using commercially available BIOMED-2 primers. Leukemia 2006;20:176–179.

Lust J . Molecular genetics and lymphoproliferative disorders. J Clin Lab Anal 1996;10:359–367.

Kim Y-C, Vandersteen D . Primary cutaneous pleomorphic small/medium-sized T-cell lymphoma in a young man. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:903–905.

von den Driesch P, Coors E . Localized cutaneous small to medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: a report of 3 cases stable for years. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:531–535.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grogg, K., Jung, S., Erickson, L. et al. Primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: a clonal T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with indolent behavior. Mod Pathol 21, 708–715 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.40

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.40

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Deciphering the spectrum of cutaneous lymphomas expressing TFH markers

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Recent advances in cutaneous lymphoma—implications for current and future classifications

Virchows Archiv (2023)

-

Therapie seltener kutaner T‑Zell-Lymphome und der blastären plasmazytoiden dendritischen Zellneoplasie

best practice onkologie (2017)

-

Therapie seltener kutaner T‑Zell-Lymphome und der blastären plasmazytoiden dendritischen Zellneoplasie

Der Hautarzt (2017)

-

Managing Patients with Cutaneous B-Cell and T-Cell Lymphomas Other Than Mycosis Fungoides

Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports (2016)