Abstract

This paper introduces methods used to communicate with participants in the ‘Biobank Japan Project (BBJP)’, which is a disease-focused biobanking project. The methods and their implications are discussed in the context of the ethical conduct of the biobanking project. Informed consent, which ensures the autonomous decisions of participants, is believed to be practically impossible for the biobanking project in general. Consequently, the concept of ‘trust’, which is ‘judgement and action in conditions of less than perfect information’, has been suggested to compensate for this limitation. As a means to maintain the trust participants feel for the project, this paper proposes communication with participants after receiving their consent. After describing the limitations of informed consent within the BBJP, based on a survey we conducted, we introduce our attempts to communicate with participants, discussing their implications as a means to compensate for the limitations of informed consent at the biobanking project.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: several features of biobanks worldwide

In this paper, authors introduce their activities of communication with participants of the ‘Biobank Japan Project (BBJP)’, which started in June 2003 with the support of the Japanese government as ‘Personalized Medicine Project’ (Box 1). Authors are involving in the BBJP, either as researchers participating in the Working Group on Public Engagement for the project or as research coordinators (RCs). We discuss the significance of communication with participants in the context of discussions related to the ethics of biobanking projects.

A biobanking project is defined for this discussion as a project to construct a ‘Human Biobanks and Genetic Research Database (HBGRD)’. Actually, HBGRD, according to the definition of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), has ‘structured resources that can be used for the purpose of genetic research (and) which include: (1) human biological materials and/or information generated from the analysis of the same and (2) extensive associated information’ (OECD 2009, Introduction, p. 1).2

Biobanking projects have been developed in countries around the world: Australia, Canada, Estonia, Iceland, Latvia, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom and the United States. As shown in Box 2, Kelley et al.3 classifies types of existing biobanking projects in these countries using five aspects: types of tissues collected, purpose, ownership, participant and size. In addition to these five aspects, types of data other than tissue samples and duration of the project can be indicators to characterize the nature of biobanks.

Established in 2003, the biggest biobanking project in the world––UK Biobank––collects blood to extract DNA, and urine as tissue samples for research purposes. It also collects data on blood pressure and lifestyle used at assessment centers established throughout the United Kingdom. The UK Biobank explains itself as a not-for-profit charitable company with investments done by three organizations.4 Although the private charities and academic institutes collaborate in managing the project, because of the level of government involvement, it is possible to define the UK Biobank as a publicly owned project. Its targeted volunteer group is the general public, aged 40–69 years: ‘population base adults’. Its participants, recruited nationally since 2007, reached 503 316 as of October 2010. In 2010, the project is still recruiting participants, who will be followed for 30 years from the point of enrolment. The end of the project is not clearly stated.

A similar biobank to the UK Biobank, in terms of tissue type, purpose, ownership and the targeted volunteer group, has been developed in Taiwan. Its data might be linked to social security numbers, the national health care insurance database and family registry information. The Estonian Biobank, whose targeted volunteer group is the general public, is governed by one university with funding once provided by venture capital but now by the government.5 In Sweden, several universities have established different biobanks with funding from an organization.6

In Canada, on the other hand, an independent organization, ‘Canadian Partnership Against Cancer’, has established the biobanking project, targeting cancer population only. Similar biobanks have also been established in the United States. The BBJP is one such disease-focused biobank.

The BBJP has been constructed as an important and symbolic infrastructural unit to facilitate research and to achieve the following aims of the ‘BBJP’: ‘(1) to discover genes susceptible to diseases onset, or those related to effectiveness or adverse reaction of various drugs, (2) to identify molecular targets for evidence-based development of drugs or diagnostic tools, (3) to identify important genetic information that is applicable for establishment of ‘Personalized Medicine’ and (4) to promote research on gene–environment interaction for disease prevention.7 The BBJP is jointly managed by The Institute of Medicine of The University of Tokyo and the RIKEN Center for Genomic Medicine since fiscal year 2003 with the support of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Participants, who were recruited at 66 cooperating hospitals nationwide in Japan, have donated their DNA, blood sera with information such as self-administered answers to life-style related questions, and clinical information stored in hospitals. After the 5-year recruitment period, approximately 200 000 patients were registered to the BBJP, who were diagnosed as having one or more of 47 targeted diseases such as atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, arrhythmia, cerebral infarction and cancer of various types. To recruit participants while reducing pressure from their physicians, the project specially trained RCs, who were in charge of explaining the protocol and obtaining consent.

However, as one observer suggests, ‘Biobanks for research pose a fundamental problem to the logic of individual autonomy and full information’. Therefore, ‘we have to be ready to find ways other than individual informed consent to secure the participants’ interests’.2 Although the issue has been much discussed in the field of ethics, no effective means to address the problem has been specified. As described in this paper, we suggest that the practice of communication can be an effective means to surmount the limitations of the informed consent that was initially provided by participants to the biobanking project, based on our experience in the BBJP. Various attempts to communicate with the BBJP participants might be consistent with this requirement of the OECD guideline, stating that. ‘The operators of the HBGRD should ensure that participants have access to regularly updated information about the type of research being carried out with the human biological materials and data contained within the HBGRD’ (OECD2009, Best Practices 3.4, p.7).2

We will also discuss the implications of communicating with the participants as a means to compensate for the limitations of informed consent by enabling participants to make autonomous decisions at any time.

Materials and methods

The paper provides an ethical perspective that might be useful in the future for coordinating genetic research with numerous participants, by offering a solution for one of the often suggested challenges, which such research often face; limitation of informed consent to enable the participants to provide informed autonomous consent. To indicate existence of such challenge within the BBJP, we first introduce the result of the survey we conducted in 2007 on the attitudes of the participants related to the contents of information they were given. The respondents are BBJP participants who regularly consult hospital ‘A’ in the suburbs of Tokyo. Using the anonymous questionnaire survey, RCs had asked participants to reflect upon and evaluate the past consent process. The research ethics committee of the Institute of Medicine of The University of Tokyo approved this survey.

We then introduce activities of communication we conducted at the BBJP after receiving consent, whose necessity was raised to tackle the limitation of informed consent indicated by the result of the survey. The activities of communication include public forums, websites, paper items and direct communication. Using these media, we have used ‘lectures’, ‘texts’ and ‘dialogues’ as methods of communication with participants.

Ethical implications of our attempts to communicate with participants will be examined in the Discussion section.

Results

Issues raised by an attitude survey of BBJP participants

During the 1-year survey period (October 2007–October 2008), we received 1378 completed questionnaires (792 men and 584 women; response rate=70.2%). The mean age of respondents was 69 years (range 7–93 years). In case of five minors, their guardians responded by proxy. We have no information related to the characteristics of non-respondents.

As shown in the Box 3, patients were explained by RCs using three tools; DVD, brochures and direct communication with RCs. In our evaluation survey, 56.9% of respondents evaluated that the DVD was ‘very understandable’ or ‘understandable’, 60% with brochures. Direct explanation by RCs was most highly evaluated as understandable (76.8%) by participants for above all three methods (Table 1). However, 34.9% of participants replied that ‘they do not remember the contents of the consent process’. Despite the fact that RCs spent at least half an hour to provide information about the project with an information brochure and a 10 min DVD before receiving consent from the participants, it has been suggested that participants often misunderstand or forget important details of their participation. However, this trend shows no statistically significant correlation with ‘time’, including ‘age’ or ‘the year they received their explanation’.

On the basis of the consent process shown in Box 3, along with the protocol, RCs were very careful to emphasize that personal data would not be disclosed to each participant because of a lack in clinical significance. According to our questionnaire to ask their attitudinal change after participation in the BBJP, the most significant trend is that 60.4% of them became interested in knowing their personal analyzed data. Table 2 shows statistically significant correlation with younger participants, better memory about the consent process (self evaluation), higher satisfaction with the consent process and willingness for future participation (P<0.01). Results show that this ‘new desire’ does not relate to insufficiency of the consent process, but it developed over time.

In addition, RCs have reported that participants frequently ask the question: ‘For what am I participating?’ Such a question also indicates that it is difficult to expect the participants of the BBJP to fully understand and remember the information provided during the consent process. Participants are all patients. Therefore, ‘testing misconception’, might have been generated by participation of the BBJP, as well as ‘therapeutic misconception’ generated by clinical trials. This problem experienced in the BBJP overlaps with the limits of informed consent provided for biobanking projects in general, which have been discussed frequently.8, 9, 10, 11

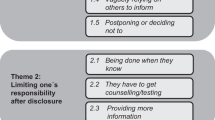

Communication methods after initial consent

The result of the survey and the report by the RCs regarding the limitedness of participants’ understanding about the contents of consent they obtained suggested the necessity to keep informing the participants about the condition of their participation in the project. Thus, in addition to the opportunities for communication the BBJP has been providing from the early stage of its establishment such as public forums and a website targeting the general publics, (By the end of 2009, 18 public forums had been conducted in 11 cities throughout the country, with each event hosting 570 participants, on average. In addition, our website has been providing various information about the project sorted under six categories; ‘Overview of the project’, ‘Materials to introduce the project’, ‘Announcements from the project’, ‘Results of the research’ ‘Information for researchers interested in the sample distribution’ and ‘Frequently asked questions’) newsletter and the communication media specifically targeting the participants, is now published regularly (It was also suggested at the meeting of the Committee for Ethical, Legal, Social Issues (ELSI),12 the external committee that was established to oversee the ethical operation of the project.).

The newsletter

Biobank News (Biobank Tsushin), a newsletter circulated twice a year since 2007, targets the participants of the cooperating hospitals. Readers of the letter other than the participants include RCs and medical practitioners, at these hospitals, and the project researchers. We are also mailing the newsletter to administrators of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology who are responsible for coordinating the project. Approximately 100 000 copies are circulated for each volume.

The newsletter, aside from one special edition, comprises four pages. The first page of the letter introduces a researcher, often a team leader of one of 12 research teams at the center for genomic medicine of RIKEN or others, working for ‘BBJP’. The second page is an exposition of a scientific topic related to the researcher introduced on the first page. On the third and the fourth pages, new scientific achievements and forthcoming events are announced, together with a report of past events, if any. People working for the management office are also introduced on the third or the fourth page.

A special edition, comprising short introductions of the result of the project, was created to address responses from readers. It has been reported by the RCs that the participants who read the newsletters sometimes offer comments: ‘the font size is too small’, ‘too much text, need more figures’, ‘contents are too difficult to follow’ or ‘I am not really interested in the researchers, but tell me more about the results of the research’. Some RCs also reported that the participants are apparently more interested in the pictures of the newsletters than words. We created the special edition as a response to these comments by readers.

Direct communication between the participants and researchers

Although we tried to respond indirectly to the demand of the participants to the greatest extent possible in creating the newsletters as described above, a limitation exists; a time lag in response is unavoidable and not all inquiries can be addressed with our limited capacity. We consider that direct communication enables us to learn more about the demands and inquiries of participants. Therefore, we are now planning to set up opportunities for direct communication between the participants and researchers. It should be noted however that the BBJP holds the rule that the participants are not re-contacted beyond the occasion when they donate blood once a year. Thus, in our plan to produce events for direct communication between the participants and researchers, we recruited participants for the events within this limit. Specifically, we asked RCs to recruit the participants to the opportunities for direct communication during their daily contacts with the participants for blood sampling. The RCs at several cooperating hospitals showed interest in organizing small-scale forums exclusively for participants, in which the participants can communicate directly with the researchers. Therefore, we organized a pilot event with the RCs of a cooperating hospital at the beginning of 2010.

The pilot event was held as one of a series of lectures that the hospital has been providing for its patients and neighbors. Consequently, the target of the pilot event was not exclusively the participants of the project. Nevertheless, 3 of 10 participants of the event were participants in the project. During the session, one stated that the project should have provided such opportunities earlier.

Encouraged by the positive response from the participants of the pilot event, we are now organizing another event at a different hospital, this time, exclusively for the project participants. The result of direct communication between the participants and the researchers shall be reported at further opportunities.

Discussion

The experience at the BBJP suggests that, even after the 30-min informed consent explanation, biobanking project participants can ask the question, ‘For what am I participating?’. It follows the preceding discussions on the limitations of ‘blanket consent’, the most generally adopted form of informed consent for biobanking researches including the BBJP.8, 9, 11, 13 It has been criticized that ‘blanket consent’, which allows research participants to make a one-time choice about the future use of their DNA sample13 ‘cannot be regarded true consent’ for it does not ensure the autonomous act of patients on continuing interests of the researchers in patients’ information.13 To ensure the autonomy of the participants in their decision to participate, some suggest the necessity to ‘recontact’ participants, every time the new research plan that uses banked biomaterials was proposed.13, 14, 15 However, it has also been argued that ‘a system, which required fresh consent would be extremely cumbersome and could seriously inhibit research’.15 There are empirical studies that support both positions that demand recontact and that does not.14, 16 Although the issue of recontact is still the debatable field regarding the ‘true’ informed consent for biobanking research, for either position, understanding and memory of the participants about the contents of information they receive during the process of informed consent is the key factor that affect the implication of ‘consent’ the participants provide. That is to say that, ‘blanket’ or not, if the participants do not understand or remember the contents of information they initially receive, it is difficult to regard the obtained consent fully autonomous.

Results of our survey on the attitudes of the participants related to the contents of informed consent they gave also indicate that, although most participants showed a positive attitude towards methods of informed consent, not a few forgot the contents. The fact that it does not relate to the factors such as ‘age’ and the ‘year they were explained’ suggests that one-time informed consent has limits in impressing its contents on participants in general. It was also implied that one-time informed consent cannot avoid generating desire of long-term participants to know their personal data.

Limitation of one-time ‘blanket’ consent indicated by the result of our study and difficulty to overcome it by modifying the form of informed consent discussed in the previous studies support the suggestion, ‘we have to be ready to find ways other than individual informed consent to secure the participants’ interests’.11 Thus, in this paper, we propose that communication with the participants after receiving consent be one of the ways to secure the participants’ interest by maintaining their ‘trust’ toward the project, rather than consolidating the form of informed consent.

Communication after consent as a way to maintain trust among participants

Communication with participants after their consent is received can be understood as a practice designed to maintain trust. In the discussion on the limit of informed consent, the concept of trust has been proposed as an alternative to the autonomy that informed consent is designed to achieve.1, 9, 10, 11 ‘Trust’ is the attitude of the biobanking project participants when they decide to participate in the project. As one example, Ducournau and Strand9 state that it is ‘simply impossible to predict the ultimate consequences of the research that will be performed on the data and the samples that have been collected.’ The participants ‘have to base their decision (to give their samples and information) on trust’.11 The question is how to maintain that ‘trust’ the participants initially possess when they give consent to participate.

O’Neil1 defines trust as ‘not generally a matter of affect or attitude, but of judgement and action in conditions of less than perfect information’. Therefore, the concept of trust presumes that the given information is imperfect. In addition, the duration of the relationship affects trust. Consequently, regarding the ethical conduct of the biobanking project, in which the participants must make a decision to participate in the long-term research project with limited information, ‘trust’ is the key concept. The question is, ‘how are the biobankers to recruit and treat the participants in a trustworthy manner?’11 We propose that it can be accomplished through appropriate communication with the participants, especially after receiving consent.

Difference between public engagement and communication with participants after receiving their consent

The importance of communication activities for biobanking projects has been discussed in the context of public engagement.17, 18 However, public engagement differs from communication with participants after receiving consent, as discussed in this paper. Public engagement includes activities designed to seek the understanding and support of ‘the public’ for the proposed project. In the case of the UK Biobank, the necessity of public engagement has been suggested based on the experience of public skepticism toward science and technology in the British society.17, 19, 20, 21 In other words, public engagement is regarded as a means to overcome public skepticism about the risk of the project, and to achieve ‘public consent’,15 before starting the project. Through public engagement, ‘citizens are ‘consulted’ and called upon to give their ‘consent’ to the project, and in the process, are ascribed responsibility for the decisions they make in relation to participation’.18 With this aim in mind, public forums, meetings with stakeholders and ‘public consultation’ have been organized in the UK Biobank, Australian Biobank22 and elsewhere.

Public engagement is therefore aiming to construct basic trust among the public toward the project before seeking consent to participate. On the other hand, communication after receiving consent, as discussed in this paper, is aimed at maintaining trust among the participants who have given consent in spite of the insufficiency of information provided through informed consent, presumably based on trust. Although the initial trust of the participants extended to the project was achieved through public engagement, and presented in the form of consent to participate, further communication might be necessary to preserve that trust.23 Communication particularly addresses preservation of the relationship with participants in long-term research projects. In this sense, former experiences of communication with participants in clinical epidemiology cohort studies, such as the Framingham Heart Study, which has endured since 1948, might provide useful lessons for the biobanking project.

Relevance of existing critiques against the BBJP

The BBJP has been criticized for its lack of accountability and transparency. Mainly because of the budget it required, it has been argued that the project should seek the understanding of the general public.24, 25, 26 Nevertheless, it has not been reported that the project has provided various opportunities for the public to learn about the project as it has been introduced into this paper. In addition, although it continues to be true that ‘Biobank Japan remains largely unknown to the Japanese public’,2 it is questionable whether the primary duty of the project is to seek understanding from the general public. Rather, as has already been pointed out, ‘it is more important for biobank in Japan to establish a friendly relationship with specific patients staying in cooperative hospitals than the wider public’.24 ‘Trust’ is the basis for a ‘friendly relationship’. Various attempts of the project to communicate with participants are designed to address this requirement. What must be examined, then, is the effectiveness of each attempt.

Examining the effectiveness of our approaches to communication

To examine the effectiveness of our approach to communicate with the participants, we explore the ‘accessibility’ of each approach specifically, based on the OECD guideline that states, ‘The operators of the HBGRD should ensure that participants have access to regularly updated information.’ Accessibility of communication tools by the participants can be limited by at least three factors: physical, regional and technological factors. In addition, we assess the interactivity of each attempt, for ‘trust’, to which trials of communication are to provide a mean, is the concept generated through development of a relationship between two or more actors.

First, public forums provide participants with opportunities to learn about the progress of the project directly from researchers. Further, participants can make inquiries, although not all participants can receive answers because of the size of each forum. Consequently, it can be the interactive mode of communication in the limited sense. The forum has been held at various cities throughout Japan, which could avoid a regional gap of accessibility to the opportunity. Nevertheless, because the participants are patients, it is likely that their ability to attend events held in urban centers will be limited by their physical capabilities.

Second, the website provides opportunities for participants with any level of physical condition to access updated information about the project, irrespective of the region in which they live. It also enables participants to voice their opinions directly to the project through the contact address. Nevertheless, its accessibility subsumes the technological capability to provide such access to participants; it is questionable whether the majority can access information provided through the Internet when the average project participant is over 60 years old.

Third, the newsletter provides equal opportunities for participants, who visit the hospital at least once a year to donate their sera to the project, to access the updated information. Unlike public forums and the website, the newsletter is a medium prepared exclusively for project participants. We are trying to respond to the requests of participants about the contents and the amounts of information it provides, which has been externalized in the form of a special edition. Nevertheless, it is a linear mode of communication in which participants cannot directly voice an opinion or inquiry.

Finally, a trial event for direct communication provides opportunities for participants to communicate directly with project researchers and staff. It has elicited the demands of participants for more interactive communication. Additional trials are necessary to discuss its function as a communication tool to maintain ‘trust’ among the participants. The contents of future events should be organized to enhance its accessibility and interactivity.

In summary, each of four approaches to communication with the participants of the BBJP, public forums, websites and newsletters presents certain limitations in terms of its accessibility and interactivity. Providing various opportunities is one way to ensure the accessibility of the participants for communication. At the same time, four approaches might necessitate some coordination. At the moment, the website, by its nature, combines information provided through other approaches of communication. Other approaches can use the website to enhance communication interactivity. In addition, the limitation of the present research is that it cannot provide a systematic review of the approaches of communication in terms of its function as a mode of building trust among participants. In future research, the effectiveness of various approaches of communication with the participants of the BBJP should be evaluated. The present paper presents a proposal of that various ways of communication with the participants after receiving consent might be able to compensate for limitations of informed consent, maintaining the trust the participants initially have when then they decide to participate in the project.

Conclusion

The paper described communication efforts that were undertaken after receiving consent from participants of the BBJP. Significance of these efforts was discussed in the context of ethical conduct of biobanking project. Because the characteristics of the biobanking project limit the feasibility of autonomous decision making, based on informed consent, ‘trust’ has been emphasized as an alternative concept that underscores the voluntary participation to the project. We proposed that communication with participants after receiving consent is a means to build ‘trust’ for the project among participants. A limitation of our research is that evaluation on the effectiveness of each communication tool to enhance ‘trust’ among the participants is yet to be conducted. In further research, a systematic review of each communication tool should be conducted, together with examination of the concept of ‘trust’ in the context of ethical conduct of the biobanking project.

References

O’Neill, O. Accountability, trust and informed consent in medical practice and research. Clin. Med. 4, 269–276 (2004).

OECD. Guidelines on Human Biobanks and Genetic Research Databases, OECD Publishing, France (2009).

Kelley, K., Stone, C., Manning, A. & Swede, H. Population based biobanks and genetics research in Connecticut. Virtual Office of Genomics (2007).

UK Biobank. Information Leaflet (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/docs/BIOINFOBK14920410.pdf. Last accessed: 30 June 2010).

Twyman, R Biobanks: the long game. The Human Genome (http://genome.wellcome.ac.uk/doc_WTX036455.html. Last accessed: 20 June 2010 (2007).

SWEGENE (The Postgenomic Research and Technology Programme in south Western Sweden). International Evaluation of Swedish Biobanks (2005).

Nakamura, Y. ‘BioBank Japan’ project toward the personalized medicine; from basic genome analysis to clinic. Circ. J. 69, 6 (2005).

Arnason, V. Coding and consent: moral challenges of the database project in Iceland. Bioethics 18, 27–49 (2004).

Caulfield, T. & Outerbridge, T. DNA databanks public opinion and the law. Med. Clin. Exp. 25, 252–256 (2002).

Ducournau, P. & Strand, R. Trust distrust and co-production: the relationship between research biobanks and participants. In: The Ethics of Research Biobanking (eds. Solbakk, J.H., Holm, S. & Hofmann, B.)Springer, London, 115–129 (2009).

Kristisson, S. & Arnason, V. Informed consent and human genetic database research. In: The Ethics and Governance of Human Genetic Databases (eds Matti, H., Chadwick, R., Arnason V., & Arnason, G.) 199–216 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2007).

The committee on ELSI of the project to realize personalized medicine. The Annual Report (Japan Public Health Association, Tokyo, 2005).

Caulfield, T., Upshur, R. E. G. & Daar, A. DNA databanks and consent: a suggested policy option involving an authorization model. BMC Med. Ethics 4 (2003).

Human Genetics Commission. Public Attitudes to Human Genetic Information, MORI Social Research (Human Genetics Commission, London, 2000).

International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO. Draft Report on Collection, Treatment, Storage and Use of Genetic Data (UNESCO, France, 2001).

Chen, D. T., Rosenstein, D. L., Muthappan, P., Hilsenbeck, S. G., Miller, F. G., Emanuel, E. J. et al. Research with stored biological samples: what do research participants want? Arch. Intern. Med. 165, 652–655 (2005).

Petersen, A. ‘Securing our genetic health: engendering trust in UK biobank’. Sociol. Health Ill. 27, 271–292 (2005).

Petersen, A. ‘Biobanks’ ‘engagements’: engendering trust or engineering consent?’ Genomics Soc. Policy 3, 1 (2007).

Corrigan, O. & Petersen, A. UK Biobank: bioethics as a technology of governance. In: Biobanks: Governance In Comparative Perspective (eds Gottweis, H. and Petersen, A.) 143–158 (Routledge, London, 2008).

Human Genetics Commission. Information gathering meeting on UK biobank (http://www.hgc.gov.uk/UpLoadDocs/Contents/Documents/InformationgatheringeventonUKBiobank.doc. Last accessed: 30 June 2010) (2002).

People Science and Policy LTD. Biobank UK: A Question of Trust: A Consultation Exploring and Addressing Questions of Public Trust (MRC and the Wellcome Trust, London, 2002).

McNamara, B. & Petersen, A. Framing consent: the politics of ‘engagement’ in an Australian biobank project. In: Biobanks: Governance in Comparative Perspective. (eds Gottweis, H. & Petersen, A.) 194–209 (Routledge, London, 2008).

Weber, L. & Carter, A. I. The Social Construction of Trust (Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, NY, USA, 2003).

Triendl, R. Japan launches controversial BioBank project. Nat Med 9, 982 (2003).

Triendl, R. & Herbert, G. Governance by stealth: large-scale pharmacogenomics and BioBanking in Japan. In: BioBanks: Governance In Comparative Perspective. (eds Gottweis, H. & Petersen, A.) 123–140 (Routledge, London and New York, 2008).

Iwae, S. Attitude toward public trust: the discourses of accountability and transparency in BioBank Japan. JIBL 6, 29–34 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The research presented herein was supported by funding from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. We extend our gratitude to the participants of the BBJP, especially to those who participated in the survey and the events we have conducted. We also thank all the research coordinators of the project for their insight into communications with the participants based on their daily practices. We are grateful for the support and the suggestions from the committee on ELSI on our practices. Lastly, but not least, we express our appreciation to Professor Yusuke Nakamura for supporting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, M., Inoue, Y., Chang, C. et al. For what am I participating? The need for communication after receiving consent from biobanking project participants: experience in Japan. J Hum Genet 56, 358–363 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2011.19

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2011.19

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ten years of dynamic consent in the CHRIS study: informed consent as a dynamic process

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Broad consent for biobanks is best – provided it is also deep

BMC Medical Ethics (2019)

-

The survey of public perception and general knowledge of genomic research and medicine in Japan conducted by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development

Journal of Human Genetics (2019)

-

Biobanking in Israel 2016–17; expressed perceptions versus real life enrollment

BMC Medical Ethics (2017)

-

Research participants’ perceptions and views on consent for biobank research: a review of empirical data and ethical analysis

BMC Medical Ethics (2015)