Abstract

Purpose

Recommendations for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers to disseminate information to at-risk relatives pose significant challenges. This study aimed to quantify family dissemination, to explain the differences between fully informed families (all relatives informed verbally or in writing) and partially informed families (at least one relative uninformed), and to identify dissemination barriers.

Methods

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers identified from four Australian hospitals (n=671) were invited to participate in the study. Distress was measured at consent using the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). A structured telephone interview was used to assess the informed status of relatives, geographical location of relatives, and dissemination barriers. Family dissemination was quantified, and fully versus partially informed family differences were examined. Dissemination barriers were thematically coded and counted.

Results

A total of 165 families participated. Information had been disseminated to 81.1% of relatives. At least one relative had not been informed in 52.7% of families, 4.3% were first-degree relatives, 27.0% were second-degree relatives, and 62.0% were cousins. Partially informed families were significantly larger than fully informed families, had fewer relatives living in close proximity, and exhibited higher levels of distress. The most commonly recorded barrier to dissemination was loss of contact.

Conclusion

Larger, geographically diverse families have greater difficulty disseminating BRCA mutation risk information to all relatives. Understanding these challenges can inform future initiatives for communication, follow-up and support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Identification of a BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 (hereon BRCA) gene mutation provides individuals with information on approximate cancer risks, and recommendations for risk reduction and surveillance. Female BRCA mutation carriers have a 40 to 66% lifetime risk of breast cancer, and a 13 to 46% lifetime risk of ovarian and fallopian tube cancer.1 Male BRCA carriers have an elevated risk of breast (1.2–6.8% by the age of 65)2 and prostate (8.6–15% by the age of 65) cancer.3, 4 Targeted screening, medical prevention, and risk-reducing surgery can improve survival outcomes for mutation carriers.5 Hence, to be informed of one’s BRCA mutation risk can potentially be lifesaving. Furthermore the cost-effectiveness of testing for BRCA mutation improves as more relatives are tested per proband.6

As part of the genetic counseling process, patients identified with a BRCA mutation are encouraged to disseminate the information to at-risk relatives. Information dissemination enables relatives to access genetic counseling services for predictive testing (site-specific testing). However, significant challenges are faced in dissemination. Probands may lack understanding of the risk to their wider family, and they may misinform relatives, assume it is the parent’s duty to pass on the information,7 or rely on relatives informing other relatives. Ultimately, the accuracy of risk information is reduced with each step in the communication process.8 Probands may also lack contact with relatives, and can face emotional barriers (including feelings of guilt, anxiety, and fear of burdening or upsetting relatives).9, 10, 11 In addition to the missed opportunities for diagnosis for relatives, withholding this information can lead to greater distress for the proband themselves;12 however, this aspect has not been widely studied.

Historically, genetics health professionals followed an ethos of nondirective counseling, whereby patients make autonomous decisions regarding whether to have mutation analysis.13 However, it is also the duty of genetics professionals to inform patients of the familial implications of a BRCA mutation14 and to provide support with this aspect (see Human Genetic Society of Australasia guideline 2012 GL02, “Process of Genetic Counselling”). As evidence for the benefits of surgical interventions have strengthened5 and the ambiguity around cancer prevention has lessened, genetic counseling has evolved to accept the use of directive counseling where appropriate.15

Previous studies from the United States suggest that dissemination rates vary significantly (59–77%).9, 10, 16 In Australia specifically, a 2008 study found that dissemination rates reached 78% after increased genetic counseling support, and this was positively correlated with an increased uptake of predictive testing.17 Achieving 100% dissemination is likely to be difficult given the multitude of barriers outlined above. However, identifying the characteristics of patients experiencing greater difficulty, and the specific barriers they face, can assist the counselor in developing targeted counseling interventions.

It has been well documented that BRCA mutation carriers are more likely to inform first-degree relatives (FDR) compared with second-degree relatives (SDR) and third-degree relatives, and are more likely to inform female relatives than male relatives.9, 17, 18 While these studies have provided insight into communication patterns in BRCA mutation carrying families, few studies included male BRCA carriers,19 or quantified dissemination any more specifically than “at least one relative.” To our knowledge, no Australian studies have assessed baseline dissemination (before implementation of a dissemination intervention),17 and the influence of family size, relatives’ geographical location, and Jewish ancestry on family dissemination has not been reported.

We therefore aimed to: (i) quantify current family dissemination among BRCA families; (ii) identify any differences between families who inform all at-risk relatives versus those who do not; (iii) identify the key barriers to disseminating information; and (iv) determine whether there is any correlation between family dissemination and psychological distress.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 671 BRCA carriers were invited to participate. They were identified from three New South Wales (NSW) and one Australian Capital Territory (ACT) metropolitan hospitals, where the hereditary cancer clinics had been established and supervised by the same lead clinician using the same policy for dissemination (verbal discussion at the time of results and provision of a family letter). Sixteen invitations were “returned to sender,” and relatives of ten participants notified the Hereditary Cancer Clinic of their death. Of the remaining 645 who were assumed to have received the invitation, 202 consented (31.3%) to participate.

Measures

K10

The Kessler psychological distress scale (K10), a measure of psychological distress, was completed by participants at consent to: (i) ensure any participants with serious psychological distress would be referred for counseling, and (ii) enable assessment of the association between distress and family dissemination. The ten-item K10 has a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing individuals with and without serious mental illness. It has an area under the curve of 0.85, meaning that 85% of cases are accurately classified.20 The K10 can be delivered verbally or provided for the participant to complete in writing. It collects information on the frequency of emotions experienced in the previous 4 weeks. Assessed emotions include tiredness, nervousness, hopelessness, restlessness, depression, and worthlessness. Frequency is measured on a five-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Scoring reaches a maximum of 50, with scores greater than or equal to 30 suggestive of a severe mental health issue, scores of between 20 and 29 indicating mild to moderate mental health issues, and scores of less than 20 indicating mental wellbeing. These categories have been determined according to the criteria developed by the Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression21 and have been used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics to conduct the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing.22

Condition-specific and other related health information

Participants were contacted for interview within 3 months of providing consent and a K10. During interview, they were asked about their current risk-reducing behaviors and other health-related information. This was to ensure that patients participating in the study were complying with, or understood, the current guidelines for risk management as an opportunity for clinical review. Information documented for female participants included bilateral mastectomy, tamoxifen use, compliance with breast screening recommendations, salpingo-oophorectomy, age at menopause, hormone replacement therapy use, bone mineral densitometry compliance, oral contraceptive pill use, and supplement use. Information documented for male participants included prostate screening compliance and supplement use. This section of the questionnaire was designed after reviewing the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre BRCA annual follow-up questionnaires. Current national guidelines, as published by eviQ,23 were also reviewed to ensure that the interview addressed all evidence-based risk-reducing strategies.

Dissemination activity

A family pedigree tool was used to record whether each at-risk relative was informed about the BRCA mutation risk (e.g., informed/not informed), how they were informed (e.g., by conversation, letter, or another relative), and their geographical location (e.g., Australian state/territory, or country if outside Australia). Restriction of “at-risk” relatives was consistent across all families, and included all living FDR, SDR, and cousins over the age of 18.

To consider patient- and family-related health and demographic factors as potential covariates, the following additional information based on the pedigree was extracted from the family file: any personal history of BRCA-related cancer, inheritance (maternal versus paternal versus unknown), whether the participant had BRCA testing as a proband or as the result of a predictive test, the number of BRCA-related cancer diagnoses in the family, the number of BRCA-related cancer deaths in family, and whether the family identified as Jewish.

Barriers to family dissemination

To identify whether participants had experienced or still faced any barriers to dissemination, a semi-structured interview script was developed by E.H., K.T. and R.W., which included prompts for discussion. Questions covered the following topics: (i) attempts made to disseminate information; (ii) how often participants thought about informing relatives; (iii) their biggest concerns; and (iv) whether a letter, review appointment, or assistance from another relative would help.

Procedure

Screening

Following receipt of consent and screening questionnaires, K10 data were analyzed to determine participants’ distress levels. Any participants scoring highly (30–50) were provided with information about their score and advised of the following options: (i) to visit the genetic counselor for an appointment to discuss their psychological health and management strategies; (ii) to request a referral from the genetic counselor to psychological services; or (iii) to make a personal appointment with their general practitioner to discuss avenues for addressing psychological difficulties. All high-scoring K10 participants were offered the opportunity to continue with the study or withdraw.

Of the eight participants who had a K10 score of greater than or equal to 30, two were already seeing a psychologist or social worker, two came for a review appointment with a genetic counselor, and four declined review/psychology referral as they felt their distress was situational and would resolve. All were followed up on average 2.1 months later and, during this period, the K10 score decreased by an average of 13.5 points.

Data collection

All measures, with the exception of the K10, were completed by the genetic counselor as part of a structured telephone interview (see Supplementary Information online for an example script). The research genetic counselor was able to view the family pedigree during the call, and used the “dissemination activity” measure to ask specifically about each branch and to record the informed status for each family member. Hand-written notes were recorded, and updates to any family history information were noted on the pedigree to be retained in the family file. Participant responses to questions, and relevant quotes referring to barriers to dissemination, were recorded by the genetic counselor.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics (means, percentages and range) for the following variables were computed: K10 score; time since test result; BRCA type (BRCA1 versus BRCA2); test type (proband versus predictive); inheritance (paternal versus maternal); family size, number of relatives informed, number of relatives tested, Jewish ancestry, proportion of relatives living in NSW; and personal and family cancer history. Numbers of BRCA-related cancers and BRCA-related deaths were counted within the affected side of the family up to and including FDR, SDR, and cousins. Cancer of the breast, ovary, fallopian tube, prostate and pancreas were all included. Melanoma was excluded due to the high population incidence in Australia.24 Statistical analysis was conducted using the software package SPSS.25 A P-value of equal to or less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Quantifying family dissemination

The following equation was used to calculate family dissemination rate:

When more than one family member consented for the study, data from the first to consent were used for analysis. Families of individuals who had informed all at-risk relatives were classed as “fully informed” and those with one or more uninformed relatives were classed as “partially informed.”

Identifying differences between families who informed all at-risk relatives versus those who did not

Categorical differences between fully informed and partially informed families were examined using chi-squared tests. Independent sample t-tests were used to measure differences in fully informed and partially informed families according to continuous variables.

Factors affecting family dissemination

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether the following participant and family factors predicted the likelihood of complete dissemination: age, sex, family size, K10 score, geographical location of relatives, ancestry (Jewish or not Jewish), BRCA type, test type, time since result, patient cancer history, and family cancer history.

Qualitative analysis

Analysis of the barriers to dissemination of information to relatives was guided by the conceptual framework of Miles and Huberman.26 Responses from 200 participants were included in this analysis. The researcher developed a master list of codes based on the first 20 interviews. As data collection took place concurrently, open coding allowed for the emergence of any new themes in addition to pre-existing ones. At completion, the occurrence of each barrier was tallied using the “autonomous counting” framework described by Hannah and Lautsch.27 Counts were used to determine the most commonly reported challenges. Comparisons were made between counts in affected and unaffected individuals to see if a personal experience of cancer led to differing perceptions regarding dissemination challenges. Illustrative quotes were chosen to add depth and voice to the recorded barriers.

Results

Participants

In total, 202 individuals participated. Two were excluded from the analysis because data were incomplete or because there were no at-risk relatives. The remaining 200 participants came from 165 separate families, and 2,591 at-risk relatives were associated with these families. The demographics of the 165 families are listed in Table 1. In summary, the mean age of the cohort was 55 years, the majority were females (83.6%) and most identified as BRCA carriers through predictive testing (61.2%). A small proportion of the cohort was of Jewish ancestry (18.8%).

Family dissemination

On average, 81.1% of at-risk relatives had been informed about the BRCA mutation carrier risk in the family, and all participants had informed at least one relative. Percentages of each relative type informed are shown in Figure 1. Informing rates were highest amongst siblings, followed by parents and children, aunts/uncles, nieces/nephews, and lowest in cousins. Of the 165 participating families, 87 families (52.7%) had not informed at least one at-risk relative, and an average of 6.5 individuals per family had not been informed. In these partially informed families (4% of first degree 27% of second degree and 62% of cousins were uninformed), 35.9% of relatives had not been informed about their BRCA carrier risk, 4% of whom were FDR, 27.0% of whom were SDR, and 62.0% of whom were cousins.

Differences between fully informed and partially informed families

The characteristics of fully informed and partially informed families are summarized in Table 2. Fully informed families were significantly smaller than partially informed families (on average, they had 6.36 fewer relatives). Fully informed families had a smaller number of siblings (0.52 fewer), nieces/nephews (2.89 fewer) and cousins (2.98 fewer). Fully informed families had, on average, significantly fewer BRCA-related cancer deaths (a difference of 0.51). Personal cancer history and the presence of BRCA cancer in a FDR were not related to dissemination status.

Participants with a fully informed family were significantly younger (approximately six years). The number of years since result receipt was similar in both fully and partially informed groups. No significant difference was found between maternal versus paternal transmission, testing type (proband versus predictive), the sex of the participant, and the family dissemination status. A higher proportion of Jewish families (61.3 versus 44.0%) had complete dissemination; however, this was not statistically significant.

Individuals with partially informed families had significantly higher K10 scores than those with fully informed families (a difference of 2.31).

The logistic regression model (Table 3) was able to accurately predict the dissemination status of 72.7% of families. In this model, decreasing family size, age, and K10 score (lower distress) were all significantly associated with an increased likelihood of complete dissemination. A higher proportion of relatives living in close proximity and a greater number of living relatives with a BRCA-related cancer were also significantly associated with complete dissemination. Ancestry and sex were not associated with dissemination.

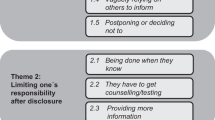

Barriers to informing relatives

Participants from both fully and partially informed families were asked to recall the barriers to informing their relatives (Table 4). Coding revealed final themes based on five key barrier domains: emotion, loss of contact, language/education, misunderstanding, and dissemination responsibilities. Loss of contact was the most commonly spontaneously reported barrier, and was mentioned by 47.5% of participants overall. In 17.5% of families, an assumption that another relative had passed on the information contributed to lack of certainty regarding dissemination. Emotional barriers, language and education barriers, and misunderstanding were reported less frequently.

Discussion

BRCA carriers hold important health information that is relevant for blood relatives. Despite the fact that we reported a higher dissemination rate than has been shown previously,9, 10, 16 a dissemination rate of 81.1% is still suboptimal. In our study sample, which was taken from four NSW/ACT hospitals alone, this represents 556 at-risk relatives yet unaware. Our finding that rates of dissemination are lower in SDR and cousins is consistent with previous reports.9, 10, 16, 18 Larger, geographically diverse, families have greater difficulty informing all relatives, largely due to the barriers of lost contact and reliance on other relatives to pass the information on.

Informing distant relatives is an integral aspect of ensuring the public health benefit of predictive testing. Informing one or more cousins can provide new information to an entire family branch and, for those who seek testing, health outcomes can be improved with more targeted and timely interventions. In this study, cousins were the least likely group to receive the BRCA-related risk information. Some of the barriers to informing cousins specifically include loss of contact, superficial relationships and geographical separation,28, 29 and this was supported by our qualitative findings.

Likewise, our quantitative findings suggest that partial dissemination was predicted by a higher proportion of relatives living interstate or overseas. Online communication resources such as Kintalk—a website which assists families to securely store and share genetic information via an online platform30—may prove to be useful for geographically diverse families. Networking websites, such as Facebook, which are more popular among young and middle-aged populations, may explain the greater likelihood of complete dissemination in younger participants.

Some participants had not directly discussed the BRCA gene with their extended relatives, but believed that they would be aware due to the strong family history of cancer. In the case where cousins do not communicate, two relatives may unnecessarily both seek proband testing. Not only is the cost of predictive testing in this case higher (AU$1,000 versus AU$300 per patient in 2016), but ongoing costs may occur when a distant relative in an established BRCA family tests inconclusive (when they might otherwise be considered a true negative), and is given risk management information in line with a high-risk family.31 Thus, explaining to patients which relatives are at-risk is an important aspect of the genetic counseling process, and this needs to be done early on. ShaRIT,32 an information package developed in the United States, may assist with this and could ultimately increase patient knowledge, as well as the number of relatives informed of a BRCA mutation risk. While improvements were noted in the ShaRIT study, the small sample size in the pilot study was not powered to detect a significant effect.32

Affected individuals were more likely than unaffected individuals to rely on other relatives to pass on the information, suggesting that treatment fatigue may be a barrier to dissemination, and is illustrated by the quote “There was so much going on in my life, I left it up to her [sister].” Identifying “key” relatives to support the communication process may also reduce the burden for the tested individual and/or increase the number of relatives informed.

While not statistically significant, the finding that fully informed families had, on average, a higher number of aunts/uncles (and lower numbers of other relatives) may suggest some benefit of having more living aunts and uncles to assist in the process of disseminating information to cousins. Conversely, in families where aunts and uncles are deceased, there may be loss of contact with cousins. Another potential explanation is the notion that it is the parent’s duty to pass genetic risk information onto their own offspring.7 Thus, by informing a sibling or aunt/uncle, an individual relinquishes the responsibility of informing their niece/nephew or cousin.

In this study, there was a greater likelihood of complete dissemination in families with a larger number of living relatives with a BRCA-related cancer. It is possible that these relatives advocate for predictive testing and thus assist with information dissemination. Life events, such as a new cancer diagnosis or death in the family, or providing care to relatives with cancer, have been previously reported to foster family communication about cancer risk.33

While identifying key relatives to assist with communication may be of some benefit, the “whispers game” effect can hinder the quality of the risk information passed onto the wider family, with each step in the communication process reducing accuracy of recall.8 A potential area for future research may be to determine whether the presence of a key relative in a follow-up appointment, who hears the information first hand from the health professional, benefits information accuracy and dissemination. Providing patients with written information and clinician-written letters to distribute to their relatives has long been established as a useful dissemination strategy and ensures that the message is not distorted.32, 34

Evidence from this study suggests that there is an association between distress and dissemination; however, is it difficult to discern whether distressed patients are less likely to inform all relatives or whether a lack of complete dissemination can contribute to distress. Individuals who are less likely to share results tend to express ambiguity around risk-reduction strategies and have fatalistic beliefs,35 which supports the former hypothesis. Individuals who share information with their relatives can gain emotional support and assistance with medical decision making, which may foster psychological adaptation36 supporting the latter hypothesis. Lapointe et al.37 found that sharing test results was not significantly associated with psychological impact. Further research is needed to discern the relationship between psychological coping and the dissemination of BRCA mutation-related risk information to family members.

Limitations

This study has noteworthy limitations. First, the K10 scale used was a generalized scale, which is not specific to BRCA concerns and which asks patients to consider how they have been feeling in the previous 4 weeks. The score could therefore be situational or related to recent illness, grief, work and relationship stress, or a number of other factors. In the future, it may be more appropriate to use a standardized scale that addresses BRCA-related stress, such as the Psychological Adaptation to Genetic Information Scale38 or the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment.39

Second, individuals who participate in studies are likely to be more motivated, and therefore more likely to have informed the majority of their relatives. In this study, the baseline rate of dissemination was 81.1%, which was slightly higher than in the majority of other studies reported in the literature.9, 10 Another explanation for this is that participants in this study had been identified with a BRCA mutation an average of 6.2 years previously, allowing significantly more time than in other studies for them to have informed their relatives. However, previous studies suggest that if BRCA carriers choose to inform relatives, they usually do so within 3–4 months of testing40, 41 and, as such, the time since the result may have a negligible effect, which is supported by our study findings.

Another limitation of this study was the inability to analyze data by hospital site. As some sites only had one clinician, it would not have been possible to maintain their confidentiality in site comparisons.

While the response rate for the study was low (31.3%), the participant group was representative of the entire cohort with respect to the male:female ratio and the uptake of risk-management choices. The participant group was, however, significantly older than the nonparticipant group (54.8 years vs. 51.3 years, t=2.57, P = 0.010). As age was found to be a predictor of dissemination, it is possible that family dissemination may be even higher in the younger nonparticipant group.

Finally, this study was carried out with participants from NSW and ACT, so we cannot be certain that these results can be generalized to wider Australian and international BRCA families. This applies particularly to jurisdictions where direct contact with relatives by genetics health professionals does not violate privacy laws. Recent changes in Australian law allow the disclosure of genetic information by a health professional to the genetic relatives of a patient where failure to disclose would place the health or life of a genetic relative at serious risk.14 One Australian study has trialed this and found that the uptake of predictive testing has significantly improved. While this may be a further avenue for increasing dissemination, consideration should be given to the additional resources required for genetic counselors to provide this additional service.

Conclusion

BRCA carriers face numerous practical and emotional barriers to attempting to disseminate cancer risk information to all of their at-risk relatives. A greater understanding of these barriers will assist the development of specific interventions. Alleviating the challenges may have positive psychological impacts for counselees, ensure that more at-risk relatives can seek genetic counseling and definitive testing, and ultimately reduce the public health burden of cancer.

References

Chen S, Parmigiani G . Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1329–1333.

Tai YC, Domchek S, Parmigiani G, Chen S . Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J. Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:1811–1814.

Leongamornlert D, Mahmud N, Tymrakiewicz M et al, Germline BRCA1 mutations increase prostate cancer risk. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1697–1701.

Kote-Jarai Z, Leongamornlert D, Saunders E et al, BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2011;105:1230–1234.

Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF et al, Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA 2010;304:967–975.

Breheny N, Geelhoed E, Goldblatt J, O’Leary P . Cost-effectiveness of predictive genetic tests for familial breast and ovarian cancer. Genomics Soc Policy 2005;1:67–79.

Forrest K, Simpson SA, Wilson BJ et al, To tell or not to tell: barriers and facilitators in family communication about genetic risk. Clin Genet 2003;64:317–326.

Vos J, Menko F, Jansen AM, van Asperen CJ, Stiggelbout AM, Tibben A . A whisper-game perspective on the family communication of DNA-test results: a retrospective study on the communication process of BRCA1/2-test results between proband and relatives. Fam Cancer 2011;10:87–96.

McGivern B, Everett J, Yager GG, Baumiller RC, Hafertepen A, Saal HM . Family communication about positive BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic test results. Genet Med 2004;6:503–509.

Finlay E, Stopfer JE, Burlingame E et al, Factors determining dissemination of results and uptake of genetic testing in families with known BRCA1/2 mutations. Genet Test 2008;12:81–91.

Nycum G, Avard D, Knoppers BM . Factors influencing intrafamilial communication of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genetic information. Eur J Hum Genet 2009;17:872–880.

den Heijer M, Seynaeve C, Vanheusden K et al, Psychological distress in women at risk for hereditary breast cancer: the role of family communication and perceived social support. Psychooncology 2011;20:1317–1323.

Kessler S . Psychological aspects of genetic counseling. XI. Nondirectiveness revisited. Am J Med Genet 1997;72:164–171.

Suthers GK, McCusker EA, Wake SA . Alerting genetic relatives to a risk of serious inherited disease without a patient’s consent. Med J Aust 2011;194:385–386.

Rantanen E, Hietala M, Kristoffersson U et al, What is ideal genetic counselling? A survey of current international guidelines. Eur J Hum Genet 2008;16:445–452.

Fehniger J, Lin F, Beattie MS, Joseph G, Kaplan C . Family communication of BRCA1/2 results and family uptake of BRCA1/2 testing in a diverse population of BRCA1/2 carriers. J Genet Couns 2013;22:603–612.

Forrest LE, Burke J, Bacic S, Amor DJ . Increased genetic counseling support improves communication of genetic information in families. Genet Med 2008;10:167–172.

Claes E, Evers-Kiebooms G, Boogaerts A, Decruyenaere M, Denayer L, Legius E . Communication with close and distant relatives in the context of genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in cancer patients. Am J Med Genet A 2003;116A:11–19.

Hallowell N, Ardern-Jones A, Eeles R et al, Communication about genetic testing in families of male BRCA1/2 carriers and non-carriers: patterns, priorities and problems. Clin Genet 2005;67:492–502.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ et al, Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:184–189.

Andrews G, Slade T . Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust N Z J Public Health 2001;25:494–497.

Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, Andrews G . The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National survey of mental health and well-being. Psychol Med 2003;33:357–362.

Cancer Institute NSW. eviQ Cancer Treatments Online 2013. https://www.eviq.org.au/. Accessed 18 August 2013.

Erdmann F, Lortet-Tieulent J, Schuz J et al, International trends in the incidence of malignant melanoma 1953-2008—are recent generations at higher or lower risk? Int J Cancer 2013;132:385–400.

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, version 20.0. Armonk, NY, 2011.

Miles MB, Huberman AM . Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage:: London, 1994.

Hannah DR, Lautsch DR . Counting in qualitative research: why to conduct it, when to avoid it, and when to closet it. J Manage Inq 2011;20:14–22.

Ratnayake P, Wakefield C, Meiser B et al, An exploration of the communication preferences regarding genetic testing in individuals from families with identified breast/ovarian cancer mutations. Fam Cancer 2011;10:97–105.

Lafreniere D, Bouchard K, Godard B, Simard J, Dorval M . Family communication following BRCA1/2 genetic testing: a close look at the process. J Genet Couns 2013;22:323–335.

Lynch HT, Snyder C, Stacey M et al, Communication and technology in genetic counseling for familial cancer. Clin Genet 2014;85:213–222.

Senter L, O’Connor M, Oriyo F, Sweet K, Toland AE . Linking distant relatives with BRCA gene mutations: potential for cost savings. Clin Genet 2014;85:54–58.

Kardashian A, Fehniger J, Creasman J, Cheung E, Beattie MS . A pilot study of the sharing risk information tool (ShaRIT) for families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2012;10:4.

Lapointe J, Cote C, Bouchard K, Godard B, Simard J, Dorval M . Life events may contribute to family communication about cancer risk following BRCA1/2 testing. J Genet Couns 2013;22:249–257.

McClellan KA, Kleiderman E, Black L et al, Exploring resources for intrafamilial communication of cancer genetic risk: we still need to talk. Eur J Hum Genet 2013;21:903–910.

Taber JM, Chang CQ, Lam TK, Gillanders EM, Hamilton JG, Schully SD . Prevalence and correlates of receiving and sharing high-penetrance cancer genetic test results: findings from the Health Information National Trends Survey. Public Health Genom 2015;18:67–77.

Wiseman M, Dancyger C, Michie S . Communicating genetic risk information within families: a review. Fam Cancer 2010;9:691–703.

Lapointe J, Dorval M, Nogues C, Fabre R, GENEPSO Cohort, Julian-Reynier C . Is the psychological impact of genetic testing moderated by support and sharing of test results to family and friends? Fam Cancer 2013;12:601–610.

Read CY, Perry DJ, Duffy ME . Design and psychometric evaluation of the Psychological Adaptation to Genetic Information Scale. J Nurs Scholarsh 2005;37:203–208.

Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A et al, A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire. Health Psychol 2002;21:564–572.

Patenaude AF, Dorval M, DiGianni LS, Schneider KA, Chittenden A, Garber JE . Sharing BRCA1/2 test results with first-degree relatives: factors predicting who women tell. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:700–706.

Montgomery SV, Barsevick AM, Egleston BL et al, Preparing individuals to communicate genetic test results to their relatives: report of a randomized control trial. Fam Cancer 2013;12:537–546.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the study was provided by the Translational Cancer Research Network. We are very grateful to the patients for their participation in this study. We also thank Christina Signorelli, Benjamin Daniels, and Emma Doolan for their advice on data analysis, and Lena Caruso and Deidre Hopkins from the Translational Cancer Research Network for their support with the project.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This project was approved by the Institutional review boards at the four participating hospitals (Prince of Wales Hospital, St George Hospital, Wollongong Hospital, The Canberra Hospital). Signed or electronic consent was obtained from all participants.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Emma Healey was involved in study design, ethics submission, patient recruitment, telephone interview, documentation, statistical analysis and manuscript preparation. Natalie Taylor was involved in manuscript preparation and review. Rachel Williams and Sian Greening were involved the study design, ethics submission, monitoring study progress/data collection, and manuscript review. Claire E Wakefield contributed to the study design, ethics submission, statistical analysis and manuscript review. Linda Warwick was involved in study design and manuscript review. Kathy Tucker contributed to the overall study design, ethics submission, monitoring study progress/data collection, and had a large involvement in the manuscript preparation and review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Tucker has chaired meetings and given lectures for AstraZenica but AZ has nothing to do with this study.

Additional information

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Healey, E., Taylor, N., Greening, S. et al. Quantifying family dissemination and identifying barriers to communication of risk information in Australian BRCA families. Genet Med 19, 1323–1331 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.52

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.52

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Direct notification by health professionals of relatives at-risk of genetic conditions (with patient consent): views of the Australian public

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Cascade genetic testing for hereditary cancer syndromes: a review of barriers and breakthroughs

Familial Cancer (2024)

-

Proband-mediated interventions to increase disclosure of genetic risk in families with a BRCA or Lynch syndrome condition: a systematic review

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Patient-reported anticipated barriers and benefits to sharing cancer genetic risk information with family members

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Examining the uptake of predictive BRCA testing in the UK; findings and implications

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)