Abstract

Purpose: Effective communication of DNA-test results requires a sound terminology. However, the variety of terms in literature for DNA-test results other than pathogenic, may create inconsistencies between professionals, and misunderstanding in patients. Therefore, we conducted a theoretical and empirical analysis of the terms most frequently used in articles between 2002 and 2007 for BRCA 1/2-test results other than pathogenic.1

Design: We analyzed the content validity of the no-pathogenic DNA-test result-terms by comparing the literal and intended meaning of the terms and by examining their clarity and the inclusion of all relevant information. We analyzed the reliability of the terms by measuring the strength of association between terms and their meanings and the consistency among different authors over time.

Results: Two hundred twenty-seven articles with 361 no-pathogenic DNA-test result-terms were found. Only two terms seemed to have acceptable validity: variant of uncertain clinical significance and no-pathogenic-DNA-test-result. Only variant of uncertain clinical significance and true negative were found to be used reliably in the literature.

Conclusions: Current DNA nomenclature lacks validity and reliability. Transparent DNA-test result terminology should be developed covering both laboratory findings and clinical meaning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Because more and more genes are being identified, several guidelines have been developed to standardize the naming and symbolization of genes, changes in genes, and protein sequences. Guidelines for human gene nomenclature were first published in 1979 and were later updated.1 Several suggestions for further standardization have been made.2–5 However, these guidelines only focused on naming changes in DNA and protein sequences. No guidelines have been developed for the communication of no-pathogenic DNA-test results (NPDTRs), i.e., when suspected pathogenic changes are not detected in mutation analysis in individual patients. Should we communicate such findings to patients as “negative,” “no-pathogenic,” or “uninformative”?

These no-pathogenic DNA-test results (NPDTRs) are frequently found. For example, pathogenic mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer are only found in about 10% of tested probands from breast cancer families. In about 80% of all tested probands, no BRCA1/2 mutation is identified. In the remaining 10%, a BRCA1/2 variant, often a missense mutation, is detected for which the clinical significance regarding cancer risks is not known; future research may show this variant to be a disease-causing mutation or a benign polymorphism.

When a pathogenic BRCA1 mutation is found, lifetime cancer risks of 65% to 85% for breast and 39% to 69% for ovarian cancer are communicated to the counselee; when a pathogenic BRCA2 mutation is found, breast cancer risks of 45% to 84% and ovarian cancer risks of 11% to 27% are communicated.6–10 On the basis of these risks, possible risk management options are discussed, such as surveillance and prophylactic surgery of breasts and/or ovaries. However, in the NPDTR, decisions about surveillance and prophylactic surgery and DNA testing in relatives are based on the family pedigree and cancer history.11

The communication of NPDTRs is often a difficult process because of the involvement of several groups of people. Molecular geneticists have to interpret DNA-test results correctly and convey these to clinicians. Subsequently, clinicians have to translate DNA-test results understandably to patients who have to recall DNA-tests outcomes correctly, act accordingly, and disclose these outcomes correctly to relatives. Moreover, molecular and clinical geneticists from different genetic centers should provide consistent information to their colleagues, patients, and relatives.

Indeed, NPDTRs seem to be regularly misunderstood by the patients.12–15 Such misunderstandings may affect medical decisions, such as prophylactic surgery after disclosure of unclassified variants.16 Moreover, sound terminology is sine qua non for the unrestrained scientific development and dissemination of genetic knowledge, especially in the light of the persistent increase of the number of articles on NPDTRs.

Words are important instruments for the genetic counselor, whose main task is transmitting information about inheritance, DNA-test results, and possible management options. The specific wording may influence how patients and other professionals understand, interpret, memorize, and attach consequences to the result. This article analyzes the geneticist's linguistic instrument both theoretically (i.e., content validity) and empirically (i.e., reliability) in a similar way as each scientific instrument should be reviewed. The aim is to test current nomenclature, select sound terms, and suggest improvements.

METHOD

Preparatory literature study

We initially conducted a literature study to select relevant terms referring to NPDTRs and to identify all possible meanings that could be given to NPDTRs. We focused on the specific aspects of terms, like “negative DNA-test result,” and not on general nouns like “mutation” or “DNA-change.”

A literature search was performed in the Pubmed for NPDTR terms used in the articles between 2002 and 2007 at April 5, 2008. This search entry was developed by a psychologist (J.V.), a clinical geneticist (C.J.v.A.), and a librarian (J.W.S.). This article is restricted to BRCA1/2 genes for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, because most mutation analyses are requested for these genes. We did not include search criteria for polymorphism and noncarrier, because these terms were already often mentioned in the articles found by other search criteria. We marked all NPDTR terms in the title, abstract, and method section of each article. Subsequently, we identified clarifications and possible meanings of NPDTR terms.

The following search query was used in PubMed: “Genes, BRCA2” [Mesh] OR “Genes, BRCA1”[Mesh] OR BRCA1-gene OR BRCA1-genes OR BRCA2-gene OR BRCA2-genes OR BRCA 1-gene OR BRCA 1-genes OR BRCA 2-gene OR BRCA 2-genes OR BRCA-gene OR BRCA-genes OR “BRCA gene” OR “BRCA genes” OR BRCA1/2[tw] OR “BRCA 1/2”[tw] OR ((brca OR brca*) AND (gene OR genes OR genetic OR genetic*))) AND (inconclusive[All Fields] OR nonconclusive[All Fields] OR “non-conclusive”[All Fields] OR “not conclusive”[All Fields] OR “not-conclusive”[All Fields] OR “uninformative”[All Fields] OR “not informative”[All Fields] OR “non-informative”[All Fields] OR “non informative”[All Fields] OR “non-informative”[All Fields] OR noninformative[All Fields] OR unclassified[All Fields] OR “not classified”[All Fields] OR “not-classified”[All Fields] OR “true-negative”[All Fields] OR “informative negative”[All Fields] OR “not pathogenic”[All Fields] OR “not-pathogenic”[All Fields] OR “non-pathogenic” [All Fields] OR nonpathogenic[All Fields] OR “without pathogenic”[All Fields] OR “uncertain pathogenic”[All Fields] OR “unknown pathogenic”[All Fields] OR “indeterminate” OR “uncertain significance” OR “uncertain relevance” OR “uncertain meaning” OR “unknown significance” OR “unknown relevance” OR “unknown meaning” OR “uncertain clinical significance” OR “uncertain clinical relevance” OR “uncertain clinical meaning” OR “unknown clinical significance” OR “unknown clinical relevance” OR “unknown clinical meaning” OR “uncertain biological significance” OR “uncertain biological relevance” OR “uncertain biological meaning” OR “unknown biological significance” OR “unknown biological relevance” OR “unknown biological meaning” OR “uncertain pathological significance” OR “uncertain pathological relevance” OR “uncertain pathological meaning” OR “unknown pathological significance” OR “unknown pathological relevance” OR “unknown pathological meaning” OR “mutation negative” OR “mutation-negative” OR “negative test result” OR “negative result” OR “negative DNA test result” OR “negative test-result” OR “negative-result” OR “negative DNA-test result” OR “negative DNA-test-result”. The resulting reference list can be requested from the authors.

Analysis of content validity

Our theoretical analysis comprised an analysis of the content validity of NPDTRs. Content validity is often regarded as the most fundamental kind of validity and measures the degree to which an instrument (here: a term) is representative of the entire concept that the instrument is designed to measure: does the term “say what we want it to say” and does it include all essential elements? Measuring content validity involves a nonstatistical analysis of the term in relationship to what the author means by this term followed by an evaluation of the validity in terms of “strong,” “acceptable,” or “weak.” We evaluated each term on four aspects: a comparison of the literal and intended meaning, clarity of the subject, inclusion of relevant information, and potential misunderstanding by patients.

First, a panel of a molecular geneticist (J.T.W.), a clinical geneticist (C.J.v.A), and two psychologists (J.V. and A.T.) discussed the literal meaning of each term, identified the underlying intended meaning of each term, and compared literal and intended meaning. To identify the literal meaning, we used dictionaries and internet engines, such as Van Dale English-Dutch, Oxford English Dictionary, Babylon English-English, Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary, Roget's Thesaurus, Google, and Wikipedia. To identify the intended meaning, we used the results from our literature study.

Second, we evaluated whether the subject of the term was specific enough to understand what the term precisely refers to, by means of a semantic analysis and with the help of the literature study. For instance, the concrete meaning of the expression “clinical meaning” is unclear and cannot be derived from the term variant of uncertain clinical meaning.

Third, we discussed whether all relevant clinical information could be derived from the formulation of the term itself, e.g., the reference to the clinical meaning is absent in the term unclassified variant but is generally mentioned in the term variant of uncertain clinical meaning.

Fourth, we identified potential misunderstanding by patients resulting from the ambiguity of the term. For example, patients may experience false reassurance after disclosure of a so-called inconclusive DNA-test result, which does not provide information about the pedigree or possibility of a false-negative DNA test.17,18 Patients may also experience false alarm when a so-called unclassified variant is found, “because something is found, thus there must be something wrong.”16

Each of these four aspects was evaluated in terms of “weak,” “acceptable,” or “strong.” We combined these four evaluations in an assessment of the total validity of each term. Total validity was determined on basis of the sum of the evaluations of the four aspects. Differences in opinion were discussed until agreement was achieved.

Analysis of reliability

Our empirical analysis assessed how reliably NPDTR terms are used in the articles by different authors over time. Measuring the reliability of words requires other measures than measuring the reliability of a physical device or a questionnaire. In general, reliability describes the consistency of a measuring instrument with regard to different raters (interrater reliability) or to measurements at different moments (test-retest reliability). Applied to terms, reliability refers to how consistent different authors use a term by giving it one specific meaning (interauthor consistency) or how consistent a term receives the same meaning over time by different authors (temporal consistency).

To be able to measure reliability, each term was classified according to its meaning. First, we assigned each term to one of the eight terminological groups and then grouped each term by its meaning (A–H in Table 1). For example, the authors of Article 116 used the term unclassified clinical variant, which we assigned to Group 5 of “unclassified-variants.” The authors used this term to refer to “a mutation with unknown clinical meaning,” which led us to classify this term for Article 1 in Group A. Two raters (J.V. and C.J.v.A.) performed the classification after agreement was attained on differences in a consensus meeting. Terms and meanings were entered in SPSS14.

The interauthor consistency/agreement was calculated by dividing the number of articles that used a specific meaning by the total number of articles using this term (see Table 3). Perfect interauthor consistency means that 100% of the authors give a term the same meaning. Some authors may have unintentionally given a different meaning to a term; however, if this is a complete coincidence, we expect at most 5% of all authors doing this and 95% of all authors giving one term the same meaning. Therefore, a term is called reliable if 95% of all authors give one term the same meaning.

Second, we calculated associations between terms and meanings with χ2. Good reliability is operationalized as a significant χ2 association of a term with its most frequently reported meaning and an insignificant χ2 association with other meanings, e.g., the term unclassified variant most frequently means “mutations with unknown clinical meaning,” and this term should therefore have significant associations with this meaning and insignificant associations with other meanings such as “pathogenic mutation.”

Third, perfect temporal consistency means that each term has the same meaning over several years. This is operationalized as a nonsignificant χ2 test between meaning and year of publication.

RESULTS

Preparatory literature study

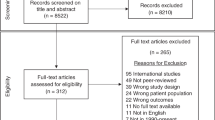

The literature search yielded 227 articles, of which 16 articles did not show relevant terms and 9 articles were only retrievable as abstracts. No articles were found with search terms referring to “not/non/uncertain/unknown pathogenic,” so these terms were removed from further analysis in the reliability study.

From the 202 remaining articles, 361 NPDTR terms were identified. We identified eight similar groups of terms, viz. inconclusive (non/not conclusive), uninformative (not/uninformative), true negative (informative negative), unclassified variant (not classified), variant of uncertain significance (variant of uncertain clinical significance/relevance/meaning/pathogeneity), polymorphism, negative, and noncarrier (points 1–8 in Table 1).

Identification of meanings of the terms resulted in eight different groups (see letters A–H in Table 1), e.g., the term noninformative was sometimes used to only refer to (B) “absence of any mutations that has no clinical meaning for the patient,” but this term is sometimes used to refer (E) both to “absence of any mutations, which either has or has no clinical meaning,” and “absence of changes with clinical meaning.”

Analysis of content validity

Table 2 shows the results of the content validity. The literal and intended meanings were largely similar for most terms: inconclusive and uninformative (both do not give definitive answers to the questions of patients and/or geneticists), variant of uncertain clinical significance (referring to the indefinite status of the clinical meaning of this DNA-variant), and NPDTR (referring to not having detected a pathogenic mutation).

The term nonpathogenic DNA-test result seemed less accurate than the term no-pathogenic DNA-test result (NPDTR), because the former term stresses the presence of a DNA-test result and the latter stresses the absence of a pathogenic mutation. Literal and intended meanings were slightly similar in the terms polymorphism and noncarrier but the former does not say that the DNA locus has “multiple forms” and that this is found in >1% of the population; the latter does not cover the intended essence of not carrying a mutation of the specific gene. The term unclassified variant is incorrect, because many variants may be classified into categories of estimated potential pathogeneity19,20 and the intention is to cover the indefiniteness of the functional and/or clinical meaning of this DNA variant. The terms negative DNA-test results and true-negative DNA-test result are incorrect, because the intention is to refer to the absence of a mutation and not to the negation of a DNA-test result.

The subject to which most terms refer is rather unclear, except for the terms variant of uncertain clinical significance and nonpathogenic DNA-test result. The following subjects are indistinct: “inconclusive,” “uninformative,” “reliably negated” (regarding true-negative results), “unclassified,” “negated” (negative result), “has multiple forms” (polymorphism), or “not-carried” (noncarrier). It is impossible to derive from the literal meanings of these terms what DNA-test results are intended: pathogenic mutation, family-specific mutation, variant with undetermined clinical meaning, benign, or disease-related polymorphism.

Except for the term true negative, much relevant clinical information could not be derived from the literal meaning of the terms. Lacking information was for e.g., risks and risk management should be based on the pedigree, possibility of a mutation in yet unknown genes, sensitivity and insensitivity of DNA testing, future research showing clinical meaning of unclassified variants and variants of uncertain clinical significance, and polymorphisms are found in >1% of the population.

All terms are to some extent ambiguous and may lead to misunderstandings in the patients, resulting in false reassurance (i.e., “nothing is detected, so I'm not at risk”) or false alarm (i.e., “something is found, so I'm at risk”).

The theoretical analysis was completed with a panel judgment of the total validity of each term. Validity was only judged as acceptable for the terms NPDTR and variant of uncertain clinical significance. The other terms have weak content validity.

Analysis of reliability

Each term in each article was classified into a group of terms (1–8 in Table 1) and into a group of meaning (A-H in Table 1). Classification into a terminological group was uncomplicated.

Classification according to the meaning was difficult for the term noninformative in 25% of all articles, for polymorphism in 20%, for negative in 12.5%, and for the terms inconclusive and noncarrier in 5% of all articles (see Table 3).

The following results were both found in the total literature study as in separate analysis in which only articles were included that were classified without difficulty. Articles about psychological topics written by psychologists did not show different results from articles about nonpsychological topics written by physicians and are therefore not separately presented.

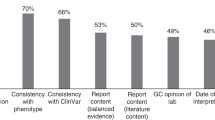

Frequency analyses indicated that the terms unclassified variant, variant of uncertain significance, and true negative were given the same meaning by >95% of all authors, implicating strong interauthor consistency. Consistency among authors was more imperfect, and thus less reliable, for the terms noninformative (85% of all authors gave this term the same meaning), inconclusive (72%), negative (71%), and poor for polymorphism (53%), and noncarrier (52%).

Four terms related significantly to their relevant meaning: inconclusive and noninformative, true negative, unclassified variant, and variant of uncertain clinical significance. Three terms significantly related to irrelevant meanings: polymorphism, negative, and noncarrier.

Most terms seemed to express the same meaning over time, except for the terms polymorphism and negative: in articles since 2004, the term polymorphism has been more consistently used as a group name for benign and disease-related polymorphisms, and the term negative is more consistently used as “absence of any mutation, with clinical meaning” (χ2 = 30.0, df = 16, P = 0.02; χ2 = 75.9, df = 40, P = 0.001, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Conclusions

Effective communication of DNA-test results requires a sound DNA terminology given the often far-reaching consequences of test results for patients. Nomenclature has received much attention in the field of molecular genetics,1 in contrast with the communication of NPDTRs, which has received little attention in the field of genetic counseling. This has caused a multiplicity of words to have evolved over time.

Our analyses showed a lack of validity and reliability for most of the terms currently used for NPDTRs in BRCA1/2. The terms variant of uncertain clinical significance and no-pathogenic DNA-test result showed acceptable or strong validity. The terms unclassified variant, variant of uncertain significance, and true negative were used reliably among different authors over time. Other terms were difficult to classify and were used unreliably and the term no pathogenic was not found in our literature study.

The lack of sound terminology could be attributed to the absence of evidence-based guidelines and to the involvement of several specialisms. The inconsistency of genetic terminology in general may reflect the fast nonsystematic development of genetics as a rather young field. However, more recently some terminological consistency seems to have been developed, as shown by the terms polymorphism and negative, which are more consistently applied since 2004.

Suggestions for new DNA terminology

To our knowledge, this is the first article studying the reliability and validity of nomenclature for NPDTRs systematically. Previous articles discussed the inconsistent use of several terms and the lack of content validity.21 The absence of previous studies may be due to the belief that terms are mere symbols to refer to phenomena. For instance, why should we worry about the precise formulation, when both the terms unclassified variant and variant of uncertain clinical significance superficially refer to the same phenomenon? This may be called a “referential view on language.” We subscribe to the reverse view of constructivism: reality is, at least partially, cognitively constructed by the words and interpretations people use.22–26 Therefore, subtle differences in wording may influence the patient's understanding, interpretation, and memory of information. This may especially account for ambiguous and important information, such as NPDTRs, where patients seem to clutch at every straw of information.16

To facilitate communication among professionals and with patients, we suggest to use or develop terms that have shown validity and reliability, like the terms variant of uncertain clinical significance and no-pathogenic DNA-test result.

Terms should have a complete correct literal meaning, like these two terms have. Incorrectness may obstruct effective communication between physicians and with patients.

The strength of the former term, variant of uncertain clinical significance, may lie in the combination of both molecular-genetic information (variant) and clinical information (uncertain significance). Other terms only mention molecular-genetic or clinical information, or neither as shown in Table 2. Whether a term has to communicate all six aspects that we identified could be questioned. In any case, terms seem to be more unclear and ambiguous when they either exclusively cover molecular genetic information, e.g., unclassified variant or exclusively cover clinical meaning, e.g., uninformative. We suggest using terms that cover both functional/molecular-genetic and clinical meaning.

The strength of the term no-pathogenic DNA-test result may lie in keeping close to the factual laboratory finding, i.e., not finding a pathogenic mutation and having a completely clear subject. Unambiguous, completely transparent expressions should be used. For example, “absence/presence of a mutation,” “with/without clinical meaning,” or “the presence of a pathogenic-mutation is not-shown.” Which terms are preferred may depend on the knowledge level of both the messenger and the receiver of the information: molecular and clinical geneticists may speak among each other about “positive/negative DNA-test results,” but this may be translated to a patient as “presence/absence of a mutation.”

The term no-pathogenic DNA-test result is also paralleled by the term pathogenic DNA-test result in literature and in practice. The linguistic relationships between these two terms are clear and balanced, in contrast with most DNA-test result terminology, which has unclear unbalanced terminological relationships. For instance, the term unclassified variant might imply the use of the term classified variant in literature; however, the term classified variant is seldom used.

The most important argument to use either variant of uncertain clinical significance or NPDTR is that patients should be able to understand and correctly interpret genetic terms and communicate them reliably to their relatives. In our opinion, the patient's perception should be the gold standard in developing medical terminology, because experts often seem to overestimate the layperson's knowledge and understanding of specialist knowledge.27,28 Focus groups of both patients and professionals could be a useful tool for establishing a sound genetic terminology29 that could be the basis for unified guidelines. Both clinicians, molecular geneticists, and patients should be involved in the practical formulation of understandable unambiguous model test reports.21 We also suggest to confirm the results of our theoretical and literature study in praxis by analyzing how DNA-test results are actually and differently formulated by molecular geneticists, clinicians, patients, and others.

REFERENCES

Wain HM, Bruford EA, Lovering RC, Lush MJ, Wright MW, Povey S . Guidelines for human gene nomenclature. Genomics 2002; 79: 464–470.

Ad Hoc Committee on Mutation Nomenclature. Update on nomenclature for human gene mutations. Hum Mutat 1996; 8: 197–202.

Beutler E, McKusick VA, Motulsky AG, Scriver CR, Hutchinson F . Mutation nomenclature: nicknames, systematic names and unique identifiers. Hum Mutat 1996; 8: 202–206.

Antonarakis SE, the Nomenclature Working Group. Recommendations for a nomenclature system for human gene mutations. Hum Mutat 1998; 11: 1–3.

Den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE . Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum Mutat 2000; 15: 7–12.

Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT, et al. Breast and ovarian-cancer incidence in Brcai-mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 56: 265–271.

King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB . Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science 2003; 302: 643–646.

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 676–689.

Antoniou A, Pharoah PDP, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 1117–1130.

Chen S, Parmigiani G . Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 1329–1333.

Vink GR, van Asperen CJ, Devilee P, Breuning MH, Bakker E . Unclassified variants in disease-causing genes: nonuniformity of genetic testing and counselling, a proposal for guidelines. Eur J Hum Genet 2004; 13: 525–527.

Claes E, Evers-Kiebooms G, Boogaerts A, Decruyenaere M, Denayer L, Legius E . Diagnostic genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in cancer patients: women's looking back on the pre-test period and a psychological evaluation. Genet Test 2004; 8: 13–21.

Hallowell N, Foster C, Ardern-Jones A, Eeles R, Murday V, Watson M . Genetic testing for women previously diagnosed with breast/ovarian cancer: examining the impact of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation searching. Genet Test 2002; 6: 79–87.

Bish A, Sutton S, Jacobs C, Levene S, Ramirez A, Hodgson S . No news is (not necessarily) good news: impact of preliminary results for BRCA1 mutation searches. Genet Med 2002; 4: 353–358.

Kelly K, Leventhal H, Andrykowski M, et al. Using the common sense model to understand perceived cancer risk in individuals testing for BRCA1/2 mutations. Psychooncology 2005; 14: 34–48.

Vos J, Otten W, van Asperen CJ, Jansen A, Menko FH, Tibben A . The counsellees' view of an unclassified variant in BRCA1/2: recall, interpretation and impact on life. Psychooncology 2008; 17: 822–830.

Dorval M, Gauthier G, Maunsell E, et al. No evidence of false reassurance among women with an inconclusive BRCA1/2 genetic test result. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005; 14: 2862–2867.

van Dijk S, Otten W, Timmermans DR . What's the message? Interpretation of an uninformative BRCA1/2 test result for women at risk of familial breast cancer. Genet Med 2005; 7: 239–245.

Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Pruss D, et al. A systematic genetic assessment of 1,433 sequence variants of unknown clinical significance in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer-predisposition genes. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 873–883.

Plon SE, Eccles DM, Easton D, et al. Sequence variant classification ands reporting: recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum Mutat 2008; 29: 1282–1291.

Lubin IM, McGovern MM, Gibson Z, et al. Clinician perspectives about molecular genetic testing for heritable conditions and development of a clinician-friendly laboratory report. J Mol Diagn 2009; 11: 162–171.

Sapir A . selected writings of Edward Sapir in language, culture, and personality. California: University of California Press, 1983.

Putnam H . The meaning of ‘meaning.’, In: Putnam H, editor. Philosophical papers: Vol. 2. Mind, language and reality. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1975; 215–271.

Rorty R . Philosophy and the mirror of nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Whorf B . Language, thought, and reality: selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. New York: MIT Press, 1956.

Lakoff G . The contemporary theory of metaphor. In: Ortony A, Metaphor and thought, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993; 202–251.

Bromme R, Rambow R, Nückles M . Expertise and estimating what other people know: the influence of professional experience and type of knowledge. J Exp Psychol Appl 2001; 7: 317–330.

Nickerson RS . How we know—and sometimes misjudge—what others know: imputing one's own knowledge to others. Psychol Bull 1999; 125: 737–759.

Lasset C, Charavel M, Bonadona V . Focus groups approach for developing written patient information in oncogenetics. Genet Test 2007; 11: 193–197.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Dutch Cancer Society for their financial support of this study (Grant no. UL2005-3214). We thank our librarian J. W. Schoones for his help with formulating the search query.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vos, J., van Asperen, C., Wijnen, J. et al. Disentangling the Babylonian speech confusion in genetic counseling: An analysis of the reliability and validity of the nomenclature for BRCA1/2 DNA-test results other than pathogenic. Genet Med 11, 742–749 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181b2e608

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181b2e608