Abstract

Purpose

Asian Americans have been understudied in the literature on genetic and genomic services. The current study systematically identified, evaluated, and summarized findings from relevant qualitative and quantitative studies on genetic health care for Asian Americans.

Methods

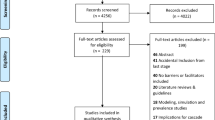

A search of five databases (1990 to 2018) returned 8,522 unique records. After removing duplicates, abstract/title screening, and full text review, 47 studies met inclusion criteria. Data from quantitative studies were converted into “qualitized data” and pooled together with thematic data from qualitative studies to produce a set of integrated findings.

Results

Synthesis of results revealed that (1) Asian Americans are under-referred but have high uptake for genetic services, (2) linguistic/communication challenges were common and Asian Americans expected more directive genetic counseling, and (3) Asian Americans’ family members were involved in testing decisions, but communication of results and risk information to family members was lower than other racial groups.

Conclusion

This study identified multiple barriers to genetic counseling, testing, and care for Asian Americans, as well as gaps in the research literature. By focusing on these barriers and filling these gaps, clinical genetic approaches can be tailored to meet the needs of diverse patient groups, particularly those of Asian descent.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Genetic counseling and genetic testing (GC/GT) are being increasingly integrated into clinical care, transforming the ability to tailor diagnostics, prevention, and treatment. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of data regarding Asian American patients’ experiences with GC/GT. Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in the United States, with a population of more than 20 million as of 2015.1 Asian Americans are a heterogeneous group with a wide spectrum of socioeconomic profiles, educational backgrounds, and linguistic characteristics.2 In genetic research, Asian American subgroups are frequently combined into a single Asian category, masking this heterogeneity.3

To increase uptake and maximize benefits, genetic services must be tailored and sensitive to cultural values of Asian American populations, as these values have been found to influence perceptions of genetic services.4 For example, the reputation of the family factors heavily into Asian American patients’ decisions regarding prenatal testing, pregnancy termination, and disclosure of family medical history.5 This is related to the view held by some Asian cultures that the family is the central unit, and medical decision-making is the responsibility of the group instead of the individual.6 Some patients may be more familiar with a paternalistic or directive model of health care often used in Asian countries. Thus, Asian immigrants may struggle with Western, nondirective styles of genetic counseling.7

While practitioners must be aware of patient–provider cultural differences, there is a potential to stereotype Asian American patients. One stereotype frequently applied to Asian Americans is the “model minority” myth.8 Applied to health care settings, this is the belief that Asian Americans do not experience health disparities to the same extent as other racial minority groups.9 Asian Americans are sometimes mistakenly assumed to have both good physical health and to have the financial resources to take care of themselves. Not only does this myth homogenize the perception of Asian Americans, but this stereotype can also have negative health implications when it is indiscriminately applied. In reality, Asian Americans face their own unique set of health disparities.10,11

Research suggests that providers are less likely to follow evidence-based guidelines and implement standards of care in preventing or managing some conditions with Asian American patients compared with patients from other racial groups.12,13 Additionally, Asian Americans have been excluded from national health databases and public health interventions.12 Canedo et al.’s recent (2019) systematic review on racial and ethnic differences in knowledge and attitudes about GT included only one small qualitative study of Chinese American participants of the 12 studies reviewed.14 Critically, this review did not include findings from any other Asian American groups. They found consistent patterns of lower awareness, lower factual knowledge scores, and more concerns about GT among non-White groups compared to Whites, but it was unclear whether the findings applied broadly to other Asian American groups.

Systematic reviews that integrate qualitative and quantitative studies capture beliefs, attitudes, decisions, and experiences in both depth (qualitative approach) and breadth (quantitative studies).15 Mixed methods systematic reviews offer a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena than single method reviews, and are increasingly recognized as important in evidence-based decision-making for health care and policy.16

Deeper understanding of the GC/GT experiences of Asian Americans is necessary for outreach and policies to properly address the needs of this uniquely diverse group. The current study was developed to identify, evaluate, and summarize the findings of relevant qualitative and quantitative studies on a specific health related issue (GC/GT) for a specific population (Asian Americans). A secondary goal was to investigate how researchers defined this population and in what detail. This paper focused on Asians living in the United States and excluded results from international Asian populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Five electronic databases (PubMed, Embase [Elsevier], PsycINFO [ProQuest], CINAHL [EBSCO], Social Science Abstracts [EBSCO]) were searched in February 2019 to execute a Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) mixed methods systematic literature search.17 The following terms were included as controlled vocabulary and keywords: “genetic counseling” OR “genetic testing” AND “Asian” OR “Asian American”. The 21 largest Asian American ethnic groups were included in our search with simply the ethnic title, for example “Chinese”, or combined with the term “American”, as in “Chinese American” (see Table 1 for full list of Asian and Asian American terms). If available in the databases, subject-related terms of the keywords were used, for example “genetic testing” included subject terms such as “genetic screening” or “predictive genetic testing”.

English language articles were included in the review if they were published between January 1990 and January 2019 in peer-reviewed journals that reported on the specific experiences of Asian Americans that had GC/GT for any genetic conditions. We included qualitative articles focused on specific psychosocial issues as experienced by Asian Americans who have undergone GC/GT as well as quantitative measures of hypothetical attitudes, family communication, and provider perceptions of patient experiences. We excluded articles that focused on medical genetics (with no patient experience data), did not clearly define an Asian population, and were published in languages other than English. The final search strategy included the following keywords, which were categorized in two groups: (1) genetic counseling OR genetic testing AND (2) Asian OR Asian American.

The selection process was performed using Covidence software.18 All papers were first reviewed on the basis of the title and the abstract. When in doubt, the article was included in next phase of review. Duplicates were deleted in both the initial reference upload to Covidence as well as in the full text review. Two researchers reviewed the remaining full text articles. Qualitative and quantitative data were extracted from included studies and full text articles were reviewed in alphabetical order of first author. Data extracted included participant demographics, study methods, the type of service studied (GC, GT, or both), and the definition of the Asian group or subgroup studied (see Table 2). Table 2 also shows other populations included in each study by the labels in the original study. The term “Hispanic” was most often used to describe White Hispanic participants but also used independently of a racial category, so here we use the term “Hispanic” without a racial modifier. In addition, 1–5 key findings were extracted from each study relevant to the review’s research question.

The JBI convergent integrated approach for mixed methods systematic review was used in this review, and quantitative data were converted into “qualitized data”.17 This involved transformation of the quantitative results from experimental and observational studies (including the quantitative component of mixed methods studies) into textual descriptions or narrative interpretation. Assembled “qualitized” data and qualitative data were categorized and pooled together based on similarity in thematic meaning to produce a set of integrated findings in the form of broad categories and second-order themes. Due to the large variety of study designs in our sample, we did not conduct a formal quality assessment and no studies were excluded based on quality.

RESULTS

Systematic literature search

Identification of relevant studies

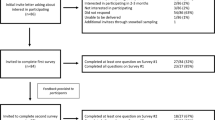

We identified a total of 8,522 papers in the first phase (Fig. 1). We excluded a majority of papers based on study sample (they did not focus on Asian American groups) or because the research was focused on medical genetics or gene expression in Asian populations, rather than on patient experiences or preferences. Based on title and abstract reviews, we selected 312 studies. During full text review, 265 studies were excluded for reasons listed in Fig. 1, 95 of which were conducted outside the United States. In total, the search resulted in 47 studies that met our inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of the studies

Article characteristics

Articles focused on the awareness, attitudes, decision-making, and experiences of Asian Americans towards GC/GT. Most studies (n = 34, 79%) focused on risk assessment and predictive testing for hereditary cancers (breast, ovarian, and colorectal), prenatal procedures (cell-free DNA, amniocentesis, prenatal genetic implantation testing), and prenatal testing for specific conditions (autism, Down syndrome, hemochromatosis, deafness). The majority of studies used quantitative methods such as surveys, questionnaires, and review of electronic medical records (n = 32, 68%), while the remaining studies employed qualitative methods such as focus groups and in-depth interviews (n = 15, 32%).

Sample characteristics

Very few studies specified which Asian subgroup was included in the research sample. Most (n = 31, 66%) used one overarching category of “Asian” for participants. Only 16 studies (34%) specified one or more Asian American populations in the research sample. These studies included participants who identified as Hmong, Vietnamese, Chinese, Korean, Indian, or Pakistani. Five studies did not specify the gender of participants. All of the 38 studies that did specify gender had a female majority, and over half had female-only participants (n = 20, 43%). Some studies included data from patients who had undergone genetic counseling (n = 11, 23%), testing (n = 10, 21%), or both (n = 2, 4%). Other studies included responses to hypothetical questions about genetic counseling and testing (n = 16, 34%). Four studies included interview or survey data collected from providers such as genetic counselors, primary care physicians, and interpreters regarding their experiences working with Asian American patients.

Qualitative and quantitative synthesis

Themes identified across studies

Our analyses identified six themes: (1) access to and awareness of genetic services, (2) GC and GT uptake, (3) attitudes toward GT, (4) communication challenges, (5) family factors, and (6) cultural factors (see Table 3).

-

1)

Access to and awareness of genetic services

Asian Americans experienced challenges in accessing GC/GT. One study found that Asian American women were referred for genetic services at a lower rate than White women.19 Another study found that Asian American parents had more limited access to GT than White, Black, and Hispanic parents.20 In another study, Asian Americans were unfamiliar with their family health histories and unable to share information with their health care providers, missing a crucial opportunity for identification of hereditary illness.21

Asian Americans had some of the lowest levels of awareness about specific genetic tests compared to other racial groups.20,22,23,24,25 One study found low awareness was correlated with other demographic variables such as low socioeconomic status (SES) or more recent immigration to the United States.20 Another study found that differences in awareness of GT services between White and Asian Americans was explained by nativity and the length of residency in the United States.24 Despite low awareness of GT in Asian American groups, participants were eager for more information about GT services.26

None of the studies explicitly compared multiple Asian subgroups or conditions. One study of Asian Indian and Pakistani Americans' views about cancer genetics found that most participants were aware of GT for hereditary cancer risk.27 This contrasts with the other studies mentioned above that found low levels of awareness for hereditary cancer and prenatal tests in their Asian American patients.20,22,24,28

-

2)

Genetic counseling and genetic testing uptake

Despite access challenges, the studies demonstrated that Asian Americans underwent GC/GT at high rates.19,29,30,31 Two studies that compared multiple racial groups found that this high uptake rate for Asian Americans was not statistically significantly different from White, Black, and Hispanic participants.32,33 One study found that personal history of cancer and education level were stronger predictors of GT uptake than race.34 However, another study found racial differences in GT uptake by parents of deaf or hard-of-hearing children. Specifically, parents of Asian heritage were much more likely to take their child for genetic evaluation compared to White parents.35

One important factor that Asian American patients considered during GC was the actionability of GT results. In one study, Southeast Asian patients viewed offering prenatal counseling alone, or offering to perform a prenatal genetic test without direct intervention, as ineffective and unnecessary.36

-

3)

Attitudes toward genetic testing

Asian Americans reported a range of attitudes toward, motivations for, and concerns about GT. Four studies explored actual patients motivations for undergoing GT,20,22,37,38 and ten studies queried healthy individuals’ attitudes about hypothetical testing scenarios.26,27,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44 Another seven studies surveyed pregnant patients’ attitudes toward prenatal testing.5,21,45,46,47,48,49

Asian Americans reported multiple motivations for pursuing GT. First, they reported higher perceived seriousness of illness than White Americans, which factored into their decisions to undergo GT.50 Compared with other racial groups, Asian Americans were more likely to express motivations to undergo hypothetical cancer GT because of the potential benefits to future generations of family rather than personal benefits.27

Thirteen studies reported concerns associated with GT among Asian American patients.20,22,26,36,37,38,40,42,44,45,46,51,52 These concerns included fear of genetic discrimination,26 financial concerns,26 avoidance of information about future disease risk,40 privacy concerns,40 worry about inaccurate results,46 potential negative health effects of taking too much blood,36 harmful outcomes to a fetus or pregnancy,36,38 religious beliefs against abortion,45,53 interference with pregnancy,52 and concern about miscarriage or fetal harm.44

Compared to other racial groups, Asian Americans were more concerned about the psychosocial impacts of testing and less concerned about insurance coverage issues.54 One study reported more psychosocial concerns in Asian American parents; specifically, they were more worried about their ability to emotionally handle GT results for deafness in their children.38 Two studies found that Asian Americans were less concerned than White Americans about insurance coverage and discrimination.37,38

Studies showed that pregnant patients were mostly in favor of actual or hypothetical prenatal testing such as noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS), preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), and other types of prenatal genetic tests. Asian Americans were motivated to do prenatal testing to be better prepared for the birth of a child, provide better management, and inform decisions about potential pregnancy termination.21,46,47,48,55 Additionally, Asian Americans were much more interested in PGT for nonhealth issues such as IQ and sex selection, compared to White Americans.5,49

-

4)

Communication barriers

Thirteen studies described at least one of four communication themes: (1) language barriers, (2) interpretation issues, (3) genetic literacy challenges, and (4) cultural expectations of directiveness.

Five studies brought up challenges related to language differences between Asian Americans and their providers.23,46,56,57,58 Researchers observed that Asian Americans were reluctant to ask questions during GC sessions, because they reported feeling unable to formulate their questions in English or they did not know what questions they were supposed to ask.23,58

Language also played an important role in understanding of genetic test results. Researchers found that for English-speaking participants, White Americans had higher mean understanding scores than Asian Americans.57 The same study showed that even when GT results were provided in participants’ native languages, English-speaking Asian American patients had higher mean understanding scores than Mandarin- and Vietnamese-speaking Asian American patients. The researchers also found that education was a significant predictor of accurate interpretation of GT results. However, the analysis did not compare or control for variables such as education, language, and race, so it is unclear whether English-speaking Asian Americans were more educated and thus had higher understanding.

Medical interpretation challenges for non-native English-speaking Asian Americans were commonly cited.23,39,52,56,59 Variable quality of interpretation limited patient understanding and sometimes increased misconceptions held by patients.39 This was especially true when patients relied on untrained interpreters, such as family members, to translate GC sessions.52 Additionally, participants in one study expressed that interpreters translated genetic information either too simplistically or too technically, resulting in miscommunication.23

Asian American patients sometimes misunderstood key information provided by genetic counselors that was needed to make informed decisions. In interviews after counseling sessions, patients reported challenges understanding GC, some citing that counseling was unclear or too long.52 This was due to conceptually difficult topics or complex technical content presented in GC sessions.39,56,58 Patients were sometimes unable to understand concepts of probabilities and inheritance, such as the idea that healthy parents could pass down an inherited illness to their child.52

Studies reported cultural differences regarding expectations of patient–provider communication.21,22,28,32,45 In particular, Asian American patients struggled with the common GC approach of “nondirectiveness”. Many patients hoped that providers would be more directive and offer what they would do if they were in the same circumstances. One study of Korean American women found that participants were uncomfortable with the nondirective nature of the counseling process. These patients were accustomed to having medical orders dictated to them and complying with providers’s recommendations without question.23 Another study found that participants viewed vague discussions of screening and prevention recommendations as unhelpful.58 When researchers observed GC sessions, they found that rather than answering in a clear and direct manner when patients asked questions, counselors were indirect or tried to explain context.58 When nondirective counseling was employed by geneticists, Asian American patients sought advice from individuals less knowledgeable than the provider such as their parents, immigration sponsors, or neighborhood herbalists.36

-

5)

Family factors

Twelve studies included in this analysis described the important role of family for Asian American patients undergoing GC and testing, including (1) family members’ roles in decision-making process, (2) family communication of genetic information, and (3) cascade testing patterns in Asian American families.

Family members played an important role in GT decision-making processes for Asian American patients.23,35,36,40,44,60 Decision-making occurred on three levels: group (family- or community-based), intimate partner, and individual. On the group or family level, one study of Southeast and East Asian women noted a particular emphasis on collective family decisions, rather than an individual decision for a range of prenatal tests.44 Another study of pregnant Asian American women found that they were more likely than other groups to state that their family’s feelings would heavily influence their decision to have prenatal testing.60 Korean American women considering prenatal GT said that they made phone calls to their mothers or sisters in Korea for decision-making guidance.23

Intimate partners played an important role in women’s prenatal testing decision-making. The same study of Korean American women mentioned above found that participants also tended to depend on their husbands’ decisions, especially in the case of difficult issues such as medical concerns, and were not comfortable making a decision regarding prenatal testing without their husband.23 Several studies pointed out that if a partner and patient disagreed on prenatal testing decisions, Asian American women were more likely than other groups to decline testing.23,36,60 For example, the authors of one study reported that husbands would commonly decline blood testing to determine heterozygote status for thalassemia, even when their wives were known to be heterozygotes (have thalassemia minor), and their children could be at risk for thalassemia major.36

Not all Asian subgroups expressed a preference for family members to be involved in GT decisions. For example, a study of Hmong participants found that they preferred individual consent for genetic services, not family or community consent.40

Asian Americans were selective in their communication with family members about inherited disease and related GT results, and overall, this type of family communication was lower in Asian American patients compared to other racial groups.32,39,61,62,63 One study found that this type of selective communication varied across subgroups and when compared to Mandarin- and English-speaking Asian Americans, Vietnamese-speaking Asian Americans were more willing to share information.63

Studies found that cascade testing (a systematic process for the identification and subsequent testing of blood relatives at risk for a hereditary condition) was less prevalent in Asian American families. These studies either queried the proband/patient, or included multiple family members regarding cascade testing for cancer risk or thalassemia minor in prenatal testing.36,61,62 One study reported that 75% of BRCA-positive participants had at least one relative that pursued GT, but at the same time found that when compared to other racial groups, Asian American patients were less likely to report having another family member undergo testing.61 Findings from another study of cancer GT indicated that Asian respondents were less likely to report encouraging family members to undergo testing compared to White Americans.62

Table 3 Specific issues within six themes. -

6)

Cultural factors

Studies identified a range of cultural beliefs about disease origins, human biology, and blood that influence patient communication, attitudes, values, and decisions about GT.21,22,36,38,39,52,56,64 While some studies simply mentioned that “cultural beliefs” were obstacles to communicating with patients and engaging them in genetic services,21,52,56,64 other studies specified what the actual cultural beliefs were.22,36,38,39

Cultural beliefs were presented as obstacles to GC/GT. For example, one study found that Asian American groups had beliefs about amniotic fluid and blood as “carrying the essence of life” and therefore the removal of blood for GT was feared and avoided.36 Another study found that participants were resistant to prenatal genetic diagnoses because they believed the testing would create interference and disharmony in the pregnancy.22

Several studies identified strong cultural stigma against certain illnesses that played a role in decision-making processes.5,22,36,40,44,45 Participants feared strong negative views from their communities toward conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, deafness, chronic diseases, medications, and “abnormal fetuses”. One study of Asian American women also found that participants declined GT for breast cancer risk because it might affect their ability to marry in the future.22

Clinical practice recommendations

Six studies made specific recommendations based on their data.23,36,47,52,59,64 First, studies recommended methods for more accurate language interpretation, to improve patients’ understanding of genetics. Two papers recommended bilingual/bicultural GC assistants or the use of translated GC aids/tools.36,59 Bilingual GC assistants in one study were better able to elicit cultural beliefs pertaining to health issues than genetic counselors, as clients reported feeling more at ease and often shared more detail about their feelings and beliefs when meeting with counseling aides alone.36 In another study, patients suggested that printed materials use more pictures, diagrams, and translated text to improve clarity and understanding during and after GC sessions.52,65

A second recommendation was for genetics providers to be aware that decision-making for Asian American patients can involve partners, family, and community.23 Genetic counselors and other providers are encouraged to explore and engage relationships beyond the traditional provider/patient dyad, including partners, other trusted family members, and a broader health care team. Community- and family-level precounseling genetic education was found to provide significant improvements in knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy (motivation and confidence) toward prenatal GC/GT.47

A third recommendation was for proivders to build a relationship with patients, educate themselves on the patient’s culture and educational background, and understand how to work with an interpreter.64

DISCUSSION

This systematic review provides a synthesis of the existing research on Asian American patient experiences with genetic counseling and genetic testing (GC/GT). Overall, our findings highlight key gaps in the literature and several barriers that Asian Americans face in accessing culturally appropriate care in GC/GT contexts.

This review pointed out key barriers to Asian Americans accessing GC/GT services. Specifically, low referral rates from providers are the largest obstacle to receiving GC/GT.66 Additionally, genetic literacy challenges were associated with language gaps, interpretation quality, and communication styles and presented serious challenges to the process of GC. These challenges in patient–provider communication are not new and not unique to Asian Americans, as they have also been well-documented for Hispanic and Black patients.67,68 The studies we identified pointed to the need for more extensive communication training for genetics providers who work with limited health literacy patients, including employing plain language, the teach-back method, and openness to more directive styles of counseling.69

Many studies reported that family members played critical roles in GT decisions, with many Asian American patients consulting with family about testing decisions. Several studies showed that Asian American patients were less likely to report having another family member undergo testing and were less likely to encourage family members to undergo testing compared to White Americans. Asian American patients were wary of discussing inherited disease risk, related GT, and test results. There was some variation across Asian subgroups for these findings, however, suggesting a need for further research about Asian American family communication in genetic health care. These findings also point to a need for the integration of family systems and broader community systems in GC processes for Asian American patients. Specifically, providers should integrate cultural needs in the pretesting phase. For example, they should engage patients in a conversation about who they want to include in their medical decision-making and GT decisions.

The first gap in the literature pointed out how little research identified the specific Asian American subgroup being studied and instead used a catch-all nonspecific “Asian” category. Only one-third of the studies had a clearly defined Asian American sample and none of the studies compared multiple Asian American subgroups, usually due to small sample size. Some of the studies had conflicting results for different Asian subgroups, but without explicit comparison, it is impossible to interpret these differences. Thus, the heterogeneity of this population remains uncaptured by the literature and future genetic research must include more specific measures of Asian American subtypes to compare distinct Asian subgroups.

The second gap in the literature was the lack of diversity regarding gender of participants and conditions studied. The studies included in this review were skewed toward Asian American female samples, mostly in the context of risk assessment and predictive testing for hereditary cancers, prenatal procedures, and prenatal testing for specific conditions. Similarly, much of what we know about the psychosocial experiences of patients undergoing GC/GT is from the perspective of female breast cancer patients and pregnant patients undergoing prenatal testing.70 This highlights a bias in the literature and a need for future research to include a more diverse range of patients across demographic groups, and disease/disease risk groups. Future research on Asian Americans should include more male participants and participants with noncancer genetic syndromes (i.e. cardiovascular or neurodegenerative diseases), to understand more clearly the needs of Asian American patients beyond heritable cancer and prenatal testing. Increased diversity in research populations is also important for broader applications of precision medicine to underserved groups.

The third gap this review was the lack of studies that adequately captured demographic variables beyond race or ethnicity, and the lack of multivariate analyses. Although Asian Americans overall have higher household incomes, lower poverty levels, and higher levels of educational attainment compared to the broader US population, this varies widely by ethnic group.1 Therefore, in addition to measuring race and ethnicity, future research on Asian Americans should include SES, education level, language, nativity, and immigrant status in data collection and analysis to more accurately capture this population’s heterogeneity. Without a clearer understanding of confounding or contributing factors, tools or interventions developed to support the health of Asian Americans may target the wrong issues. Future genetic research must include more specific measures that consider the intersection of Asian ethnic subgroup and the previously mentioned demographic factors.

Recommendations for genetic research and practice

To maximize benefits and minimize harms of GC/GT for Asian Americans, future research should prioritize three things. First, studies must be more inclusive and specific to a range of Asian population subtypes and disease risk groups. Second, study designs must facilitate comparison across diverse racial groups and Asian subgroups. They should elucidate cultural nuances and incorporate potentially confounding factors such as acculturation, immigrant status, and education level. Third, more health services research is needed to develop and test strategies to tailor genetic services to fit unique racial and cultural patient contexts.

Another important implication of this research is the need for increased funding for research with historically marginalized groups, such as Asian Americans. A recent analysis found that after 2000 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget spent only 0.18% of its total budget on Asian American and Pacific Islander–focused clinical research.71 Federal entities must dedicate funds to increase diversity in research populations, otherwise, research on Asian American populations may continue to languish.

For GC/GT to address persistent health inequalities, researchers must address barriers to research participation. Researchers should increase recruitment of underrepresented groups, including Asian Americans, and build trust among these populations. Participants must be invested and believe there is value in providing information about themselves and their families, and that research participation will translate to equitable distribution of benefits. Community-based participatory researchers have developed methods for engaging community members in health promotion and prevention strategies. Examples include centering Korean churches or Vietnamese-owned nail salons as community portals for delivering culturally relevant health education and medical services.72

As genetic services become more accessible to the public, clinical genetic services can and should integrate health equity research. Genetic researchers and clinicians should engage with communities, meeting people where they are and understanding their priorities to promote more inclusive approaches to genetic services and precision medicine.

Researchers and clinicians themselves must also represent the diversity of the populations they investigate and serve. NIH does not consider Asian Americans to be an underrepresented racial group in the medical research workforce and this status has “de-minoritized” Asian Americans by no longer defining them as a minority. Efforts have been made to address the lack of diversity in the genetic counseling profession through mentorship programs, special interest groups, and strategic plans, but there is still a long way to go. Racial diversity among providers can increase the depth and scope of information that patients are willing to share in the clinical setting—information that is important to their health.

Strengths and limitations of current study

While this is a critical systematic review of GC/GT on an under‐researched group, there are some important limitations. The review only included articles published in English, possibly omitting relevant studies published in other languages. This review explicitly did not compare Asian Americans with other racial/ethnic groups, however, many of the included studies framed their findings about Asian American samples in reference to White, Hispanic, and Black participant populations.

Conclusion

As GT and precision medicine interventions become more integrated into health care systems, creative strategies must be employed to ensure that health disparities in access and utilization are not perpetuated or exacerbated. The newest strategic vision for the National Human Genome Research Institute includes the bold prediction that “individuals from ancestrally diverse background will benefit equitably from advances in human genomics”.73 For this prediction to come to fruition, it is necessary to address the research gaps and health care barriers identified in this review.

Precision health researchers and clinicians must recognize the heterogeneity of the Asian population with regards to acculturation, nationality, socioeconomic status, education level, age, and health awareness. To reduce biases and overgeneralizations providers must educate themselves on multiple modalities for talking to patients and their family members about GT. Providers must also recognize that Asian American patients are individuals with unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle characteristics, and develop tailored disease prevention and clinical treatment strategies to address these unique needs.

References

Pew Research Center. Key facts about Asian Americans. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/08/key-facts-about-asian-americans/ (2017).

US Census Bureau. American Community Survey 1-year estimates. Selected population profile in the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; (2008).

Holland, A. T. & Palaniappan, L. P. Problems with the collection and interpretation of Asian-American health data: omission, aggregation, and extrapolation. Ann. Epidemiol. 22, 397–405 (2012).

Tan, E. K. et al. Comparing knowledge and attitudes towards genetic testing in Parkinson’s disease in an American and Asian population. J. Neurol. Sci. 252, 113–120 (2007).

Chen, L. S., Zhao, M., Zhou, Q. & Xu, L. Chinese Americans’ views of prenatal genetic testing in the genomic era: a qualitative study. Clin. Genet. 82, 22–27 (2012).

Wang, H., Zhao, F., Wang, X. & Chen, X. To tell or not: the Chinese doctors’ dilemma on disclosure of a cancer diagnosis to the patient. Iran J. Public Health. 47, 1773–1774 (2018).

Wang, V. & Marsh, F. H. Ethical principles and cultural integrity in health care delivery: Asian ethnocultural perspectives in genetic services. J. Genet. Couns. 1, 81–92 (1992).

Yi, S. S., Kwon, S. C., Sacks, R. & Trinh-Shevrin, C. Commentary: persistence and health-related consequences of the model minority stereotype for Asian Americans. Ethn. Dis. 26, 133–138 (2016).

Tendulkar, S. A. et al. Investigating the myth of the “model minority”: a participatory community health assessment of Chinese and Vietnamese adults. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 14, 850–857 (2012).

Gupta, L. S., Wu, C. C., Young, S. & Perlman, S. E. Prevalence of diabetes in New York City, 2002–2008: comparing foreign-born South Asians and other Asians with U.S.-born whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Diabetes Care. 34, 1791–1793 (2011).

Li, S., Kwon, S. C., Weerasinghe, I., Rey, M. J. & Trinh-Shevrin, C. Smoking among Asian Americans: acculturation and gender in the context of tobacco control policies in New York City. Health Promot. Pract. 14, 18s–28s (2013).

Islam, N. S. et al. Disparities in diabetes management in Asian Americans in New York City compared with other racial/ethnic minority groups. Am. J. Public Health. 105, S443–446 (2015).

Tung, E. L., Baig, A. A., Huang, E. S., Laiteerapong, N. & Chua, K. P. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes screening between Asian Americans and other adults: BRFSS 2012–2014. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 32, 423–429 (2017).

Canedo, J. R., Miller, S. T., Myers, H. F. & Sanderson, M. Racial and ethnic differences in knowledge and attitudes about genetic testing in the US: Systematic review. J. Genet. Couns. 28, 587–601 (2019).

Booth, A. Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a structured methodological review. Syst. Rev. 5, 74 (2016).

Aromataris, E. M. Z. E. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ (2017).

Lizarondo, L. et al. in JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (ed Aromataris, E. M. Z. E.) Chapter 8: mixed methods sytematic reviews. JBI; https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/JBI+Manual+for+Evidence+Synthesis (2020).

Covidence systematic review software. In: Innovation VH, ed. Melbourne, Australia: www.covidence.org. https://support.covidence.org/help/how-can-i-cite-covidence.

Manrriquez, E., Chapman, J. S., Mak, J., Blanco, A. & Chen, L. Disparities in genetics assessment for women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 147, 216–217 (2017).

Chen, L. S., Xu, L., Huang, T. Y. & Dhar, S. U. Autism genetic testing: a qualitative study of awareness, attitudes, and experiences among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Genet. Med. 15, 274–281 (2013).

Chen, L. S., Li, M., Talwar, D., Xu, L. & Zhao, M. Chinese Americans’ views and use of family health history: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 11, e0162706 (2016).

Glenn, B. A., Chawla, N. & Bastani, R. Barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer risk among ethnic minority women: an exploratory study. Ethn. Dis. 22, 267–273 (2012).

Jun, M., Thongpriwan, V., Choi, J., Sook Choi, K. & Anderson, G. Decision-making about prenatal genetic testing among pregnant Korean-American women. Midwifery. 56, 128–134 (2018).

Pagán, J. A., Su, D., Li, L., Armstrong, K. & Asch, D. A. Racial and ethnic disparities in awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk. Am. J. Prev. Med. 37, 524–530 (2009).

McGrath, B. B. & Edwards, K. L. When family means more (or less) than genetics: the intersection of culture, family and genomics. J. Transcult. Nurs. 20, 270–277 (2009).

Catz, D. S. et al. Attitudes about genetics in underserved, culturally diverse populations. Community Genet. 8, 161–172 (2005).

Leader, A. E., Mohanty, S., Selvan, P., Lum, R. & Giri, V. N. Exploring Asian Indian and Pakistani views about cancer and participation in cancer genetics research: toward the development of a community genetics intervention. J. Community Genet. 9, 27–35 (2018).

Krakow, M., Ratcliff, C. L., Hesse, B. W. & Greenberg-Worisek, A. J. Assessing genetic literacy awareness and knowledge gaps in the US population: results from the Health Information National Trends Survey. Public Health Genomics. 20, 343–348 (2018).

Pasick, R. J. et al. Effective referral of low-income women at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer to genetic counseling: a randomized delayed intervention control trial. Am. J. Public Health. 106, 1842–1848 (2016).

Levy, D. E. et al. Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: Black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genet. Med. 13, 349–355 (2011).

Simons-Morton, D. G. et al. Characteristics associated with informed consent for genetic studies in the ACCORD trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 37, 155–164 (2014).

Fehniger, J., Lin, F., Beattie, M. S., Joseph, G. & Kaplan, C. Family communication of BRCA1/2 results and family uptake of BRCA1/2 testing in a diverse population of BRCA1/2 carriers. J. Genet. Couns. 22, 603–612 (2013).

Heidi, A. H. et al. BRCA1/2 testing and cancer risk management in underserved women at a public hospital. Community Oncol. 9, 369–376 (2012).

Olaya, W. et al. Disparities in BRCA testing: when insurance coverage is not a barrier. Am. J. Surg. 198, 562–565 (2009).

Palmer, C. G., Lueddeke, J. T. & Zhou, J. Factors influencing parental decision about genetics evaluation for their deaf or hard-of-hearing child. Genet. Med. 11, 248–255 (2009).

Mittman, I., Crombleholme, W. R., Green, J. R. & Golbus, M. S. Reproductive genetic counseling to Asian-Pacific and Latin American immigrants. J. Genet. Couns. 7, 49–70 (1998).

Hall, M. A. et al. Concerns in a primary care population about genetic discrimination by insurers. Genet. Med. 7, 311–316 (2005).

Palmer, C. G. et al. Ethnic differences in parental perceptions of genetic testing for deaf infants. J. Genet. Couns. 17, 129–138 (2008).

Cheng, J. K. Y. et al. Cancer genetic counseling communication with low-income Chinese immigrants. J. Community Genet. 9, 263–276 (2018).

Culhane-Pera, K. A. et al. Leaves imitate trees: Minnesota Hmong concepts of heredity and applications to genomics research. J. Community Genet. 8, 23–34 (2017).

Glanz, K. et al. Correlates of intentions to obtain genetic counseling and colorectal cancer gene testing among at-risk relatives from three ethnic groups. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 8, 329–336 (1999).

Ramirez, A. G. et al. Attitudes toward breast cancer genetic testing in five special population groups. J. Health Dispar. Res. Pract. 8, 124–135 (2015).

Landry, L., Nielsen, D. E., Carere, D. A., Roberts, J. S. & Green, R. C. Racial minority group interest in direct-to-consumer genetic testing: findings from the PGen study. J. Community Genet. 8, 293–301 (2017).

Tsai, G. J. et al. Attitudes towards prenatal genetic counseling, prenatal genetic testing, and termination of pregnancy among Southeast and East Asian women in the United States. J. Genet. Couns. 26, 1041–1058 (2017).

Chen, L. S. et al. Autism spectrum disorders: a qualitative study of attitudes toward prenatal genetic testing and termination decisions of affected pregnancies. Clin. Genet. 88, 122–128 (2015).

Floyd, E., Allyse, M. A. & Michie, M. Spanish- and English-speaking pregnant women’s views on cfDNA and other prenatal screening: practical and ethical reflections. J. Genet. Couns. 25, 965–977 (2016).

Sim, S. C., Zhou, X. D., Hom, L. D., Chen, C. & Sze, R. Effectiveness of precounseling genetic education workshops at a large urban community health center serving low-income Chinese American women. J. Genet. Couns. 20, 593–608 (2011).

Tischler, R., Hudgins, L., Blumenfeld, Y. J., Greely, H. T. & Ormond, K. E. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis: pregnant women’s interest and expected uptake. Prenat. Diagn. 31, 1292–1299 (2011).

Winkelman, W. D., Missmer, S. A., Myers, D. & Ginsburg, E. S. Public perspectives on the use of preimplantation genetic diagnosis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 32, 665–675 (2015).

Saucier, J. B. et al. Racial-ethnic differences in genetic amniocentesis uptake. J. Genet. Couns. 14, 189–195 (2005).

Agrawal, S., Chennuri, V. & Agrawal, P. Genetic diagnosis in an Indian child with Alagille syndrome. Indian J. Pediatr. 82, 653–654 (2015).

George, R. Strengthening genetic services in primary care for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Community Genet. 1, 154–159 (1998).

Kuppermann, M. et al. Beyond race or ethnicity and socioeconomic status: predictors of prenatal testing for Down syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. 107, 1087–1097 (2006).

Fehniger, J. et al. Perceived versus objective breast cancer. Breast cancer risk in diverse women. J. Womens Health (Larchmt). 23, 420–427 (2014).

Sayres, L. C., Allyse, M., Goodspeed, T. A. & Cho, M. K. Demographic and experiential correlates of public attitudes towards cell-free fetal DNA screening. J. Genet. Couns. 23, 957–967 (2014).

Agather, A., Rietzler, J., Reiser, C. A. & Petty, E. M. Working with the Hmong population in a genetics setting: genetic counselor perspectives. J. Genet. Couns. 26, 1388–1400 (2017).

Harrison, H. F. et al. Screening for hemochromatosis and iron overload: satisfaction with results notification and understanding of mailed results in unaffected participants of the HEIRS study. Genet. Test. 12, 491–500 (2008).

Joseph, G. et al. Information mismatch: cancer risk counseling with diverse underserved patients. J. Genet. Couns. 26, 1090–1104 (2017).

Dixson, B., Dang, V., Cleveland, J. O. & Peterson, R. M. An educational program to overcome language and cultural barriers to genetic services. J. Genet. Couns. 1, 267–274 (1992).

Learman, L. A. et al. Social and familial context of prenatal genetic testing decisions: are there racial/ethnic differences? Am. J. Med. Genet. Semin. Med. Genet. 119 C, 19–26 (2003).

Cheung, E. L., Olson, A. D., Yu, T. M., Han, P. Z. & Beattie, M. S. Communication of BRCA results and family testing in 1,103 high-risk women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 19, 2211–2219 (2010).

Ricker, C. N. et al. Patient communication of cancer genetic test results in a diverse population. Transl. Behav. Med. 8, 85–94 (2018).

Tucker, D. C. et al. Predictors of belief that genetic test information about hemochromatosis should be shared with family members. Genet. Test. 10, 50–59 (2006).

Krieger, M., Agather, A., Douglass, K., Reiser, C. A. & Petty, E. M. Working with the Hmong population in a genetics setting: an interpreter perspective. J. Genet. Couns. 27, 565–573 (2018).

Grimes, D. A. & Snively, G. R. Patients’ understanding of medical risks: implications for genetic counseling. Obstet. Gynecol. 93, 910–914 (1999).

Swink, A. et al. Barriers to the utilization of genetic testing and genetic counseling in patients with suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.). 32, 340–344 (2019).

Browner, C. H., Preloran, H. M., Casado, M. C., Bass, H. N. & Walker, A. P. Genetic counseling gone awry: miscommunication between prenatal genetic service providers and Mexican-origin clients. Soc. Sci. Med. 56, 1933–1946 (2003).

Charles, S., Kessler, L., Stopfer, J. E., Domchek, S. & Halbert, C. H. Satisfaction with genetic counseling for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among African American women. Patient Educ. Couns. 63, 196–204 (2006).

Joseph, G. et al. Effective communication in the era of precision medicine: a pilot intervention with low health literacy patients to improve genetic counseling communication. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 62, 357–367 (2019).

Yanes, T., Willis, A. M., Meiser, B., Tucker, K. M. & Best, M. Psychosocial and behavioral outcomes of genomic testing in cancer: a systematic review. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 27, 28–35 (2019).

Ðoàn, L. N., Takata, Y., Sakuma, K. K. & Irvin, V. L. Trends in clinical research including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander participants funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw. Open. 2, e197432 (2019).

Liou, J. et al. Developing a community health worker model to incorporate patient leadership and advocacy within the Asian immigrant community: a practical perspective. Am. J. Health Stud. 22, 105–113 (2007).

Green, E. D. et al. Strategic vision for improving human health at the forefront of genomics. Nature. 586, 683–692 (2020).

Acknowledgements

J.Y. was supported by National Institutes of Health grant T32HG00895301.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y., M.C., and H.K.T. conceived of the presented idea. M.B. provided consultation regarding search terms, database selection, and systematic review methodology, and constructed search strategies. J.Y. conducted all title and abstract review, J.Y and J.M. conducted full text reviews, and H.K.T. served to resolve any disagreements. J.Y. and T.S. conducted data extraction and J.Y. performed thematic analysis. J.M., H.K.T., and M.C. reviewed the findings and aided in interpreting the results. J.Y and H.K.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Search Strategies by Database

Search Strategies by Database

PubMed

(((((((genetic screening[Title/Abstract] OR genetic testing[Title/Abstract] OR genetic predictive testing[Title/Abstract] OR genetic predisposition testing[Title/Abstract] OR genetic screenings[Title/Abstract]))) OR “Genetic Testing”[Mesh])) OR ((((genetic counseling[Title/Abstract] OR prenatal genetic counseling[Title/Abstract] OR preventive genetics[Title/Abstract]))) OR “Genetic Counseling”[Mesh]))) AND (((((Asian Cultural Groups[Title/Abstract] OR Asiatic Race[Title/Abstract] OR Asian[Title/Abstract] OR Asians[Title/Abstract] OR Chinese[Title/Abstract] OR Laotian[Title/Abstract] OR Burmese[Title/Abstract] OR Cambodian[Title/Abstract] OR Vietnamese[Title/Abstract] OR Korean[Title/Abstract] OR Japanese[Title/Abstract] OR Thai[Title/Abstract] OR Hmong[Title/Abstract] OR Filipino[Title/Abstract] OR Indian[Title/Abstract] OR Taiwanese[Title/Abstract] OR Pakistani[Title/Abstract] OR Bangladeshi[Title/Abstract] OR Indonesian[Title/Abstract] OR Nepalese[Title/Abstract] OR Sri Lankan[Title/Abstract] OR Malaysian[Title/Abstract] OR Bhutanese[Title/Abstract] OR Mongolian[Title/Abstract] OR Singaporean[Title/Abstract])) OR (Asian American[Title/Abstract] OR Asian Americans[Title/Abstract] OR Asian-American[Title/Abstract] OR Asian-Americans[Title/Abstract] OR Chinese American*[Title/Abstract] OR Laotian American*[Title/Abstract] OR Burmese American*[Title/Abstract] OR Cambodian American*[Title/Abstract] OR Vietnamese American*[Title/Abstract] OR Korean American*[Title/Abstract] OR Japanese American*[Title/Abstract] OR Thai American*[Title/Abstract] OR Hmong American*[Title/Abstract] OR Filipino American*[Title/Abstract] OR Asian Indian American*[Title/Abstract] OR Taiwanese American*[Title/Abstract] OR Pakistani American*[Title/Abstract] OR Bangladeshi American*[Title/Abstract] OR Indonesian American*[Title/Abstract] OR Nepalese American*[Title/Abstract] OR Sri Lankan American*[Title/Abstract] OR Malaysian American*[Title/Abstract] OR Bhutanese American*[Title/Abstract] OR Mongolian American*[Title/Abstract] OR Singaporean American*[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((“Asian Americans”[Mesh]) OR “Asian Continental Ancestry Group”[Mesh])).

Embase (Elsevier)

((‘asian cultural groups’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asiatic race’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asian’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asians’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘chinese’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘laotian’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘burmese’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cambodian’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘vietnamese’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘korean’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘japanese’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘thai’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘hmong’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘filipino’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘indian’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘taiwanese’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘pakistani’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bangladeshi’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘indonesian’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘nepalese’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sri lankan’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘malaysian’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bhutanese’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘mongolian’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘singaporean’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asian american’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asian americans’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asian-american’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asian-americans’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘chinese american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘laotian american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘burmese american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cambodian american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘vietnamese american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘korean american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘japanese american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘thai american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘hmong american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘filipino american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asian indian american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘taiwanese american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘pakistani american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bangladeshi american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘indonesian american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘nepalese american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sri lankan american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘malaysian american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bhutanese american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘mongolian american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘singaporean american*‘:ti,ab,kw OR ‘asian’/exp OR ‘asian continental ancestry group’/exp OR ‘asian american’/exp)) AND ((‘genetic screening’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘genetic testing’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘genetic predictive testing’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘genetic predisposition testing’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘genetic screenings’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘genetic screening’/exp) OR (‘genetic counseling’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘preventive genetics’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘prenatal genetic counseling’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘genetic counseling’/exp)) AND ((‘psychosocial factor’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘psychosocial factors’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘psychological factor’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘psychological factors’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘psychology’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘psychology’/exp)).

PsycInfo (ProQuest)

(MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Asians”) OR ti(Asian Cultural Groups OR Asiatic Race OR Asian OR Asians OR Chinese OR Laotian OR Burmese OR Cambodian OR Vietnamese OR Korean OR Japanese OR Thai OR Hmong OR Filipino OR Indian OR Taiwanese OR Pakistani OR Bangladeshi OR Indonesian OR Nepalese OR Sri Lankan OR Malaysian OR Bhutanese OR Mongolian OR Singaporean) OR ab(Asian Cultural Groups OR Asiatic Race OR Asian OR Asians OR Chinese OR Laotian OR Burmese OR Cambodian OR Vietnamese OR Korean OR Japanese OR Thai OR Hmong OR Filipino OR Indian OR Taiwanese OR Pakistani OR Bangladeshi OR Indonesian OR Nepalese OR Sri Lankan OR Malaysian OR Bhutanese OR Mongolian OR Singaporean) OR ab(Asian American OR Asian Americans OR Asian-American OR Asian-Americans OR Chinese American* OR Laotian American* OR Burmese American* OR Cambodian American* OR Vietnamese American* OR Korean American* OR Japanese American* OR Thai American* OR Hmong American* OR Filipino American* OR Asian Indian American* OR Taiwanese American* OR Pakistani American* OR Bangladeshi American* OR Indonesian American* OR Nepalese American* OR Sri Lankan American* OR Malaysian American* OR Bhutanese American* OR Mongolian American* OR Singaporean American*) OR ti(Asian American OR Asian Americans OR Asian-American OR Asian-Americans OR Chinese American* OR Laotian American* OR Burmese American* OR Cambodian American* OR Vietnamese American* OR Korean American* OR Japanese American* OR Thai American* OR Hmong American* OR Filipino American* OR Asian Indian American* OR Taiwanese American* OR Pakistani American* OR Bangladeshi American* OR Indonesian American* OR Nepalese American* OR Sri Lankan American* OR Malaysian American* OR Bhutanese American* OR Mongolian American* OR Singaporean American*)) AND (((ti(genetic testing OR genetic screening OR genetic predictive testing OR genetic predisposition testing OR genetic screenings) OR ab(genetic testing OR genetic screening OR genetic predictive testing OR genetic predisposition testing OR genetic screenings)) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXPLODE(“Genetic Testing”)) OR (ti(genetic counseling OR preventive genetics OR prenatal genetic counseling) OR ab(genetic counseling OR preventive genetics OR prenatal genetic counseling) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXPLODE(“Genetic Counseling”))).

Social Services Abstract (ProQuest)

((MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Genetic Testing”) OR ab(genetic screening OR genetic screenings OR genetic testing OR genetic predictive testing OR genetic predisposition testing) OR ti(genetic screening OR genetic screenings OR genetic testing OR genetic predictive testing OR genetic predisposition testing)) OR (ab(genetic counseling OR preventive genetics OR prenatal genetic counseling) OR ti(genetic counseling OR preventive genetics OR prenatal genetic counseling))) AND ((MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Asian Americans”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT(“Asian Cultural Groups”)) OR ab(Asian Cultural Groups OR Asiatic Race OR Asian OR Asians OR Chinese OR Laotian OR Burmese OR Cambodian OR Vietnamese OR Korean OR Japanese OR Thai OR Hmong OR Filipino OR Indian OR Taiwanese OR Pakistani OR Bangladeshi OR Indonesian OR Nepalese OR Sri Lankan OR Malaysian OR Bhutanese OR Mongolian OR Singaporean) OR ti(Asian Cultural Groups OR Asiatic Race OR Asian OR Asians OR Chinese OR Laotian OR Burmese OR Cambodian OR Vietnamese OR Korean OR Japanese OR Thai OR Hmong OR Filipino OR Indian OR Taiwanese OR Pakistani OR Bangladeshi OR Indonesian OR Nepalese OR Sri Lankan OR Malaysian OR Bhutanese OR Mongolian OR Singaporean) OR ab(Asian American OR Asian Americans OR Asian-American OR Asian-Americans OR Chinese American* OR Laotian American* OR Burmese American* OR Cambodian American* OR Vietnamese American* OR Korean American* OR Japanese American* OR Thai American* OR Hmong American* OR Filipino American* OR Asian Indian American* OR Taiwanese American* OR Pakistani American* OR Bangladeshi American* OR Indonesian American* OR Nepalese American* OR Sri Lankan American* OR Malaysian American* OR Bhutanese American* OR Mongolian American* OR Singaporean American*) OR ti(Asian American OR Asian Americans OR Asian-American OR Asian-Americans OR Chinese American* OR Laotian American* OR Burmese American* OR Cambodian American* OR Vietnamese American* OR Korean American* OR Japanese American* OR Thai American* OR Hmong American* OR Filipino American* OR Asian Indian American* OR Taiwanese American* OR Pakistani American* OR Bangladeshi American* OR Indonesian American* OR Nepalese American* OR Sri Lankan American* OR Malaysian American* OR Bhutanese American* OR Mongolian American* OR Singaporean American*)).

CINAHL (EBSCO)

(TI (Asian Cultural Groups OR Asiatic Race OR Asian OR Asians OR Chinese OR Laotian OR Burmese OR Cambodian OR Vietnamese OR Korean OR Japanese OR Thai OR Hmong OR Filipino OR Indian OR Taiwanese OR Pakistani OR Bangladeshi OR Indonesian OR Nepalese OR Sri Lankan OR Malaysian OR Bhutanese OR Mongolian OR Singaporean) OR AB (Asian Cultural Groups OR Asiatic Race OR Asian OR Asians OR Chinese OR Laotian OR Burmese OR Cambodian OR Vietnamese OR Korean OR Japanese OR Thai OR Hmong OR Filipino OR Indian OR Taiwanese OR Pakistani OR Bangladeshi OR Indonesian OR Nepalese OR Sri Lankan OR Malaysian OR Bhutanese OR Mongolian OR Singaporean) OR TI (Asian American OR Asian Americans OR Asian-American OR Asian-Americans OR Chinese American* OR Laotian American* OR Burmese American* OR Cambodian American* OR Vietnamese American* OR Korean American* OR Japanese American* OR Thai American* OR Hmong American* OR Filipino American* OR Asian Indian American* OR Taiwanese American* OR Pakistani American* OR Bangladeshi American* OR Indonesian American* OR Nepalese American* OR Sri Lankan American* OR Malaysian American* OR Bhutanese American* OR Mongolian American* OR Singaporean American*) OR AB (Asian American OR Asian Americans OR Asian-American OR Asian-Americans OR Chinese American* OR Laotian American* OR Burmese American* OR Cambodian American* OR Vietnamese American* OR Korean American* OR Japanese American* OR Thai American* OR Hmong American* OR Filipino American* OR Asian Indian American* OR Taiwanese American* OR Pakistani American* OR Bangladeshi American* OR Indonesian American* OR Nepalese American* OR Sri Lankan American* OR Malaysian American* OR Bhutanese American* OR Mongolian American* OR Singaporean American*) OR (MH “Asians + “)) AND (((MH “Genetic Counseling”) OR TI (genetic counseling OR preventive genetics OR prenatal genetic counseling) OR AB (genetic counseling OR preventive genetics OR prenatal genetic counseling)) OR ((MH “Genetic Screening”) OR TI (genetic testing OR genetic screening OR genetic screenings OR genetic predictive testing OR genetic predisposition testing) OR AB (genetic testing OR genetic screening OR genetic screenings OR genetic predictive testing OR genetic predisposition testing))).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Young, J.L., Mak, J., Stanley, T. et al. Genetic counseling and testing for Asian Americans: a systematic review. Genet Med 23, 1424–1437 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01169-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01169-y