Abstract

Purpose: Younger individuals with relatives diagnosed with cancer are at greater risk for developing certain cancer when compared with older individuals with affected relatives. The purpose of this study was to calculate the age-specific proportion of individuals reporting positive family histories for colon, breast, and prostate cancer.

Methods: Family cancer history information was reviewed on 32,374 adults interviewed for the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Family histories were categorized as high risk, with a relative diagnosed before 50 years of age or with multiple affected relatives, or moderate risk, with a single relative diagnosed at age 50 years or older.

Results: For individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer, the odds of having a high-risk pedigree decreased by 1% (95% confidence interval 0%–2%) for every year of age increase. For women reporting a family breast cancer history, the odds of reporting a pedigree with high-risk features decreased by 3% (95% confidence interval 2%–4%) for each year of age increase. Age was not associated with reporting a high-risk pedigree for prostate cancer.

Conclusion: For colorectal and breast cancers, younger individuals reporting a family history of these cancers were more likely to report a pedigree with high-risk features than older individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Individuals reporting an affected relative with certain cancers are at increased risk of developing cancers themselves.1,2 The actual risks associated with a positive family cancer history are highly dependent on both the number of affected relatives within a pedigree and the age at which an affected relative was diagnosed.3,4 Thus, individuals with a single affected relative with colorectal cancer diagnosed at the age of 70 years should be managed differently than individuals with multiple affected first-degree relatives, particularly if a relative was diagnosed before the age of 50 years.5 With numerous genetic tests available for identifying hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes, family cancer history information is becoming an increasingly important clinical tool for cancer risk assessment and management.6 To comply with most colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer-screening guidelines, providers need to collect pedigree information on patients aged 10 years or less than the age at which routine cancer screening begins for the general population.5,7,8

A significant interaction between an individual's age and his or her family history has been described for colorectal and breast cancer, but less so for prostate cancer.9–15 Younger patients with positive family histories tend to have greater age-adjusted relative risks of developing colorectal or breast cancer than older patients with positive family histories. The mechanism underlying this interaction between age and family history is unclear. One potential explanation might be that younger individuals with positive family histories are more likely to have pedigrees with high-risk features, such as relatives who are affected at earlier ages or multiple first-degree relatives affected. By using data from a population-based, cross-sectional survey, we evaluated whether younger respondents reporting a positive family history are more likely to have high-risk features.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

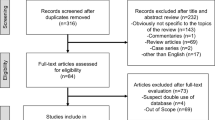

The data source for this study was the Cancer Control Module of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). The NHIS is an in-person health interview conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau for the National Center for Health Statistics. The NHIS uses a multistage probability sample design to represent current health information for the civilian, noninstitutionalized, household population of the United States. The survey has been conducted continuously since 1957 and is released publicly on an annual basis. For the year 2000 survey, the overall sample adult response rate was 72.1%.16 In 2000, a supplement to the core NHIS was the Cancer Control Module.17 This module consisted of seven sections covering health behavior, family history, and cancer screening. For the Cancer Control Module, 32,374 persons aged 18 years or more were interviewed.

Adults were asked about first-degree relatives (mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, sons, and daughters) with cancer. The survey gathered information on the number of unaffected and affected relatives, types of cancer, and number of relatives diagnosed with cancer before 50 years of age. Individuals were considered to have a positive family history if they identified any affected first-degree relative with the specified cancer of interest (breast, colorectal, or prostate). We further categorized family history into two groups: high-risk family history and moderate-risk family history based on criteria proposed by Scheuner et al.18 Individuals were considered to have a high-risk family history if one or both of the following conditions were met: (1) a single first-degree relative with breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer diagnosed before the age of 50 years or (2) two or more first-degree relatives diagnosed with the same cancer regardless of age. Individuals who reported a single first-degree relative affected with breast, colorectal, or prostate after the age of 50 years were considered to have a moderate-risk family history.

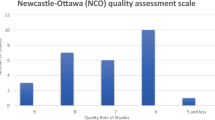

Age-specific proportions of individuals reporting a family history of colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer were calculated, stratifying by survey respondent age into 10-year intervals. The first strata included individuals ages 18 to 29 years, and the final strata included individuals 70 years or older. Family history information was then categorized into high-risk and moderate-risk family histories. To determine the proportion of individuals reporting a positive family history of colorectal cancer, all respondents were included (N = 32,374) within the analysis. For gender-specific cancers, we included only women in our breast cancer analyses (N = 18,388) and men in our prostate cancer analyses (N = 13,986). By using the NHIS recoded categorization of “white,” “black,” and “other,” we evaluated the proportion of respondents reporting any affected first-degree relatives by race. We calculated the weighted odds ratio of reporting a high-risk family history in individuals reporting any affected relative. Odds ratios were adjusted for the number of first-degree relatives and race. Odds ratios were also adjusted for a personal history of the cancer type that the individuals had identified within a relative. Each age stratum was compared with the referent group, which was age 70 years or more. To account for the NHIS multistage probability sample design, all analyses were performed using SAS-callable SUDAAN software, version 9 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). By using SUDAAN software, we calculated the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) associated with the prevalence estimates.

RESULTS

The overall proportion of any reported family history in this population was 4.4% (95% CI: 4.2%–4.7%) for colorectal cancer, 7.3% (6.9%–7.7%) for breast cancer, and 4.1% (3.7%–4.4%) for prostate cancer. The proportion of positive reports tended to increase over the age strata. The proportion of respondents reporting affected first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer was least in individuals aged 18 to 29 years of age at 0.7% (0.5%–1.0%) and greatest in individuals aged 60 to 69 years old at 9.0% (8.0%–10.3%). For women, only 2.5% (2.0%–3.2%) of those 18 to 29 years old reported any family history of breast cancer, and the proportion of women reporting a positive family history was the largest for women 70 years or older at 12.0% (10.7%–13.4%). For men, only 0.9% (0.6%–1.3%) of the 18- to 29-year-old group reported any family history for prostate cancer, compared with 6.5% (5.6%–7.6%) of men 70 years or older.

Figures 1 to 3 show the proportion of positive family histories stratified by high-risk pedigree and moderate-risk pedigree. For colorectal cancer, the proportion of individuals reporting a moderate-risk family history became significantly greater than those reporting a high-risk family history at age 40 years. This difference remained statistically significant in all subsequent age groups. Women 50 years or older with positive family breast cancer histories were more likely to report a moderate-risk pedigree compared with a high-risk pedigree, whereas women younger than 30 years were more likely to report a high-risk pedigree. For men reporting family histories of prostate cancer, there were statistically significant differences in the reporting rates of high-risk and moderate-risk pedigrees beginning at age 30 years.

Race-specific rates of individuals reporting any first-degree relative affected with colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer are presented in Table 1. Individuals categorized as “other” tended to have the lowest percentage of respondents reporting a positive family history, particularly for prostate cancer.

For individuals reporting any affected first-degree relative, the odds of reporting a pedigree with high-risk features compared with reporting a moderate-risk pedigree were calculated. After adjustment for total number of first-degree relatives, prior diagnosis of cancer, and race, individuals aged 18 to 29 years with positive family histories had the highest odds of reporting a high-risk pedigree when compared with the referent group (Table 2). For individuals reporting any first-degree relative affected with colorectal cancer, for every year increase in age, the odds of the pedigree having high-risk features decreased by 1% (95% CI 0%–2%). For women reporting a family history of breast cancer, for every year increase in age, the odds of reporting a pedigree with high-risk features decreased by 3% (95% CI 2%–4%). For prostate cancer there was no significant decrease in the odds of reporting a high-risk pedigree in individuals reporting any affected first-degree relative with prostate cancer (0, 95% CI 2%–3%).

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of a cross-sectional sample of U.S. adults, we found that although the overall proportion of individuals reporting positive family histories for colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer increased with age, the relative proportion of these histories that represented pedigrees with high-risk features decreased. As the proportion of individuals reporting a moderate-risk family history increased with age, the proportion of those reporting high-risk pedigrees increased less rapidly. As such, individuals aged less than 30 years who reported any family history for colorectal and prostate cancer were about as likely to report a high-risk pedigree as a moderate-risk pedigree. For young women, individuals reporting a positive family breast cancer history were actually more likely to report a pedigree with high-risk features than a moderate-risk pedigree.

Prior studies of colorectal and breast cancer have identified that having a family history of a disease seems to carry greater risk in younger individuals. For prostate cancer, less data exist describing this relationship. In a prospective study of family history and colorectal cancer risk, Fuchs et al.9 found that 30- to 44-year-old individuals with a positive family history of colorectal cancer had an adjusted risk ratio of developing colorectal cancer of 4.63 when compared with individuals with no family history. This risk ratio tended to decrease as individuals got older, becoming no different from that of an individual without a family history for colon cancer by age 60 years. For breast cancer, a recent collaborative reanalysis combining data from 52 epidemiologic studies on breast cancer demonstrated that among women with a single affected relative with breast cancer, the highest risk for developing breast cancer was in women aged less than 35 years, with a risk ratio of 2.91 (2.05–4.13).11 This risk ratio progressively declined with increasing age.

Our results indicate that family history was associated with a higher risk of developing cancer in younger than older individuals because the positive family histories reported by younger individuals are more likely to have high-risk features than those reported by older individuals. A partial explanation for this finding is that as individuals age, their entire family ages with them, creating more opportunities for environmental and sporadic causes of cancer to occur within a family. Similarly, younger individuals reporting positive family histories are more likely to have relatives who developed cancer at a younger age, suggesting a stronger hereditary component. These clinical implications would argue for the importance of collecting detailed family history information on younger patients, because this information may be more likely to detect individuals at higher risk for a hereditary cancer syndrome. Furthermore, these findings stress the importance of collecting more complete pedigree information on patients of all ages. This is particularly salient because the family cancer history is often incompletely and inadequately collected during clinical encounters.19 Simply using family history as “present or absent” without adjusting for age or actual risk associated with the individual's pedigree might overestimate the overall degree of risk associated with a family history in an older adult and underestimate it in a younger adult.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the NHIS Cancer Control Module only collects family history information on first-degree relatives. Thus, we may have incorrectly classified individuals with multiple affected second-degree relatives as either moderate risk or without a positive family history. Second, the NHIS relies on self-reporting to obtain family history information. However, a recent systematic review showed that self-reported family cancer histories for colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer are accurate.20 Another limitation is that we only calculated rates of family histories of colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer. Several hereditary cancer syndromes are associated with multiple tumor types, such as hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer and hereditary breast ovarian cancer. Thus, we likely underestimated the actual number of individuals with high-risk pedigrees. Finally, the NHIS does not collect exact ages for affected relatives but only whether they were diagnosed before or after the age of 50 years. Prior research has suggested that the relative ages of the proband to the affected relative can have an important effect on overall cancer risk in breast cancer.21,22

The proportion of individuals reporting any positive family history for colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer increased with patient age. Much of this increase was from individuals reporting a single affected relative diagnosed after the age of 50 years. Patients aged less than 40 years reporting any family history of colorectal or breast cancer tended to be more likely to report a pedigree with high-risk features. Clinicians should be careful to collect detailed family cancer information from their patients, particularly in younger patients.

References

Ponder BA . Inherited predisposition to cancer. Trends Genet 1990; 6( 7): 213–218.

Lynch HT, Brodkey FD, Lynch P, Lynch J, et al. Familial risk and cancer control. JAMA 1976; 236( 6): 582–584.

Pharoah PD, Day NE, Duffy S, Easton DF, et al. Family history and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 1997; 71( 5): 800–809.

Burt RW . Familial risk and colon cancer. Int J Cancer 1996; 69( 1): 44–46.

Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology 2003; 124( 2): 544–560.

Guttmacher AE, Collins FS, Carmona RH . The family history–more important than ever. N Engl J Med 2004; 351( 22): 2333–2336.

Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender R, Levin B, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. CA Cancer J Clin 2001; 51( 1): 38–75.

Smith RA, Saslow D, Sawyer KA, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003. CA Cancer J Clin 2003; 53( 3): 141–169.

Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, et al. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 1994; 331( 25): 1669–1674.

Slattery ML, Levin TR, Ma K, Goldgar D, et al. Family history and colorectal cancer: predictors of risk. Cancer Causes Control 2003; 14( 9): 879–887.

Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet 2001; 358( 9291): 1389–1399.

Rodriguez C, Calle EE, Miracle-McMahill Tatham LM, et al. Family history and risk of fatal prostate cancer. Epidemiology 1997; 8( 6): 653–657.

Lesko SM, Rosenberg L, Shapiro S . Family history and prostate cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol 1996; 144( 11): 1041–1047.

Cerhan JR, Parker AS, Putnam SD, Chiu BC, et al. Family history and prostate cancer risk in a population-based cohort of Iowa men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999; 8( 1): 53–60.

St. John DJ, McDermott FT, Hopper JL, Debney EA, et al. Cancer risk in relatives of patients with common colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118( 10): 785–790.

2000 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release: NHIS Survey Description. Hyattsville, MD: Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics; 2002.

Hiatt RA, Klabunde C, Breen N, Swan J, et al. Cancer screening practices from National Health Interview Surveys: past, present, and future. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94( 24): 1837–1846.

Scheuner MT, Wang SJ, Raffel LJ, Larabell SK, et al. Family history: a comprehensive genetic risk assessment method for the chronic conditions of adulthood. Am J Med Genet 1997; 71( 3): 315–324.

Murff HJ, Byrne D, Syngal S . Cancer risk assessment quality and impact of the family history interview. Am J Prev Med 2004; 27( 3): 239–245.

Murff HJ, Spigel DR, Syngal S . Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. JAMA 2004; 292( 12): 1480–1489.

Mettlin C, Croghan I, Natarajan N, Lane W . The association of age and familial risk in a case-control study of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1990; 131( 6): 973–983.

Peto J, Mack TM . High constant incidence in twins and other relatives of women with breast cancer. Nat Genet 2000; 26( 4): 411–414.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Health Care System, GRECC Unit, for administrative support in the preparation of the article. Dr. Murff is supported by a Career Development Award through the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center SPORE in GI Cancer Grant (CA 95103) and is a VA Clinical Research Scholar, VA Clinical Research Center of Excellence. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murff, H., Peterson, N., Greevy, R. et al. Impact of patient age on family cancer history. Genet Med 8, 438–442 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gim.0000223553.69529.84

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gim.0000223553.69529.84

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Personalized medicine and access to health care: potential for inequitable access?

European Journal of Human Genetics (2013)