Abstract

Aims

To establish the impact of adult strabismus surgery on clinical and psychosocial well-being and determine who experiences the greatest benefit from surgery and how one could intervene to improve quality of life post-surgery.

Methods

A longitudinal study, with measurements taken pre-surgery and at 3 and 6 months post-surgery. All participants completed the AS-20 a disease specific quality of life scale, along with measures of mood, strabismus and appearance-related beliefs and cognitions and perceived social support. Participants also underwent a full orthoptic assessment at their preoperative visit and again 3 months postoperatively. Clinical outcomes of surgery were classified as success, partial success or failure, using the largest angle of deviation, diplopia and requirement for further therapy.

Results

210 participants took part in the study. Strabismus surgery led to statistically significant improvements in psychosocial and functional quality of life. Those whose surgery was deemed a partial success did however experience a deterioration in quality of life. A combination of clinical variables, high expectations, and negative beliefs about the illness and appearance pre-surgery were significant predictors of change in quality of life from pre- to post-surgery.

Conclusions

Strabismus surgery leads to significant improvements in quality of life up to 6 months postoperatively. There are however a group of patients who do not experience these benefits. A series of clinical and psychosocial factors have now been identified, which will enable clinicians to identify patients who may be vulnerable to poorer outcomes post-surgery and allow for the development of interventions to improve quality of life after surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strabismus can have debilitating effects on patient’s self-esteem, quality of life and mood.1 Surgery to realign the eyes is associated with eliminating diplopia, expanding the visual field and reducing torticollis, as well as overall improvements in quality of life, patient satisfaction and confidence.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 However, this is not the case for everyone. While 95% of patients achieve clinical success 6 weeks following surgery, only 60% of patients experience a meaningful improvement in quality of life.8 This suggests that other factors may act as cofounders to successful improvements in quality of life. Cross-sectional studies suggest that depression,1, 9 beliefs the patient holds about their appearance, strabismus and its treatment,1 and the expectations patients have about post-surgical outcomes10 are all factors associated with quality of life in this population, as opposed to clinical variables. There has however, been no exploration of how these factors may impact on surgical success, or who experiences the optimal quality of life post surgery.

The studies so far conducted are often flawed by small samples, retrospective designs or short follow-ups. Hence, larger studies with longer follow-up assessments are needed.2, 11 This study therefore aims to assess how strabismus surgery impacts upon quality of life and mood in a larger population over a 6 month follow-up period. In order to understand who may benefit most from surgery and what factors could be targeted in an intervention to improve the impact of strabismus surgery on quality of life, this study will also identify the characteristics of patients who experience the greatest improvements in quality of life.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study presents the follow-up of participants who took part in a previous study.1 Between November 2010 and April 2012 consecutive adult strabismus patients listed for surgery at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London were prospectively identified. Patients were consented either on the day of being added to the waiting list or at their pre-operative assessment. Patients were excluded if they had significant co-morbidities, other facial or ocular abnormalities, or identifiable psychosis, dementia or other cognitive impairment. Approval was obtained from the North London Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

All self-report questionnaires were completed before surgery and again 3 and 6 months post surgery.

Demographic and clinical

Data were collected on age, gender, ethnicity, previous ocular and treatment history at baseline. All participants underwent a full orthoptic assessment at their preoperative visit and again 3 months postoperatively. Examination included the assessment of the direction and size of deviation at near (1/3 m) and distance (6 m) using the alternate prism cover test (PCAT) and assessment of binocular functions. For multiplanar deviations, the largest angles, targeted for surgical correction, be that at near or distance, were recorded for analysis. Diplopia/visual confusion when present was categorised into two groups based on the position of gaze in which it was present. Diplopia experienced in either primary position (straight ahead) and/or downgaze (reading position) or diplopia experienced in another tertiary gaze position during ocular motility assessment. Self-reported levels of pain, swelling, scaring and redness, as a result of surgery, were recorded on a 10-point Likert scale from 0 (no experience) to 10 (severe).

Classification of 3 month postoperative outcome

Three categories were defined: success, partial success or failure based on the surgical outcome 3 months following strabismus surgery. For success, all of the following categories had to be met (i) the largest angle of deviation for esotropia, exotropia or hypertropia <12 prism dioptres (PD) and hypotropia <20 prism dioptres,12 (ii) diplopia/visual confusion either absent or rarely appreciated in primary position and reading and (iii) no requirement for prism or bangerter foil therapy. For partial success at least one of the above categories should not be met and failure none of the above criteria met.

Primary outcome measure

The AS-2013 is a validated, strabismus-specific quality of life instrument. The measure consists of two subscales; functional and psychosocial quality of life. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Successful surgery has been defined as an increase in the psychosocial subscale of 17.7 points and 19.5 points for the function subscale, these are 95% limits of agreement (LOA).14

Psychosocial measures

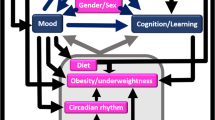

Participants also completed a series of psychosocial measures taken from the framework of adjustment to strabismus (Figure 1).1 Where possible, existing validated measures were used. A full description of the measures employed can be found elsewhere.1 In addition to these measures the following questionnaires were also completed.

Expectations of, and reasons for seeking surgery

Patients’ reasons for seeking surgery and their expectations about the benefits of surgery were measured pre-operatively using the Reasons for Strabismus Surgery Questionnaire (RSSQ) and Expectations of Strabismus Surgery Questionnaire (ESSQ).10 Each consists of three subscales: (i) intimacy and appearance-related issues, (ii) social relationships and (iii) visual functioning. Total subscale scores range from 1–5 for subscales (i) and (ii), and 1–7 for subscale (iii). Higher scores indicate stronger reasons for seeking surgery or higher expectations about the outcome of surgery.

Satisfaction

Participants were asked if they regretted having surgery, with responses on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (yes definitely) to 4 (not at all). Participants also reported on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (no hesitation at all) to 4 (certainly not) whether they would go through the surgery again.

Power calculation

The sample size was powered to look at differences in quality of life over time. As data were hierarchically structured, multilevel modelling was performed. This requires a sample size of at least 60, when there are fewer than five parameters to be estimated.15 However, in order to perform a hierarchical regression with the independent variables (IV) outlined in Figure 1, with an effect size of 0.15 and α=0.05, GPower 3.1.6 (Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) indicated a sample size of 217.

Statistical methods

Little’s missing completely at random test indicated no systematic differences between the observed and missing values (P>0.05). Ten scale-level imputation iterations were used to eliminate bias. All analyses, except for the multilevel models, were performed on each of these 10 datasets and then pooled for multiple imputation to give a final combined result.16 Differences in quality of life between levels of surgical success were explored using one-way between-groups ANOVA. Multilevel modelling was used to explore changes over time. As clinical variables were measured at only two-time points differences over time were assessed using either a Wilcoxon-Signed Rank test or McNemar's test. Hierarchical multiple regression were performed to identify the baseline predictors of changes in quality of life and which changes in the intervening psychological processes predicted changes in quality of life. The variables were added into the regression based on the framework (Figure 1). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Participants

Of the 335 patients who consented, 81.49% completed a baseline questionnaire. Of these, 210 completed either a 3 (n=41) or 6 month (n=25) follow-up questionnaire or both (n=144). Baseline characteristics of the sample can be found in Table 1.

Impact of surgery

Clinical variables

The angle of deviation decreased significantly from baseline (mean difference (Md)=30, range 2–90) to 3 months (Md=10, range 0–90; z=−11.81, P<0.001, r=−0.57). There was a statistically significant reduction in the proportion of participants who experienced diplopia from prior (58.57%) to 3 months post surgery (40%; P<0.001). A small proportion (5.85%) experienced surgery induced diplopia at 3 months, 11 in the primary and downgaze position and 1 in another gaze.

Low levels of pain, swelling, scarring and redness were reported at both 3 and 6 months post surgery, with no significant changes in pain, swelling or scarring between these two follow-ups. Improvements in redness from 3 (Md=1, range 0–10) to 6 months (Md=0, range 0–10) post surgery were significant (z=−3.51, P=0.001, r=−0.24).

Psychosocial variables

Statistically significant improvements in psychosocial and functional quality of life, anxiety and depression, social anxiety and social avoidance, illness and treatment beliefs, fear of negative evaluation, perceived visibility, and salience and valance of appearance (Table 2) were found from pre-surgery to 3 months and pre-surgery to 6 months. There were no significant changes from 3 to 6 months. Overtime the number of participants who were meeting moderate or ‘caseness’ levels of anxiety or depression, or scoring below normal in quality of life, reduced significantly from pre-surgery to 6 months post surgery, whereas the proportion of patients in the normal classification for mood and above normal in quality of life increased. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of participants who exceeded the 95% LOAs at 3 and 6 months post surgery (psychosocial quality of life: P=0.33; functional quality of life P=0.12).

Relationship between clinical success and quality of life

According to clinical criteria, 110 (52.38%) participants experienced successful surgery, 20 (9.52%) failed and 80 (38.09%) were partial successes. Of these 80 partial successes, 10 (12.5%) were scheduled for further surgery, 43 (53.75%) had been discharged from the service, 13 (16.25%) had a scheduled follow-up appointment, 9 (11.25%) were receiving prism therapy and 5 (6.25%) botulinum toxin therapy. While there were no statistically significant differences between these three groups of patients on changes in functional quality of life from baseline to 6 months (F2207=0.89, P=0.42), there were differences in changes in psychosocial quality of life (F2207=4.22, P=0.02, η2=0.04). Post-hoc comparison indicated that the mean residualised change score for those who experienced partial success (M=−0.24, SD=0.84) was significantly lower than those who experienced success (M=0.18, SD=1.05).

Satisfaction

Over 80% of patients did not regret having surgery, ~6% had some regret either at 3 or 6 months. Between 70 and 80% of the sample would go through the operation, only 1–4% would not.

Who benefits most from surgery?

The final model for changes in psychosocial quality of life explained 85% of the total variance (F49 160= 18.60, P<0.001). The statistically significant predictors were the IPQ-R consequences subscale, the intimacy and appearance-related issues subscale of the RSSQ, the DAS24 and perceived visibility at baseline (Table 3). The final model for changes in functional quality of life explained 72% of the variance (F49 160=8.60, P<0.001). The statistically significant predictors were ethnicity, classification, the IPQ-R consequences subscale, the TRI treatment concern subscale, the visual functioning subscale of the ESSQ and RSSQ, and DAS24 at baseline (Table 3).

Which concepts should be targeted in order to improve the impact of surgery?

The final model for changes in psychosocial quality of life accounted for 78% of the variance (F19 190=35.78, P<0.001). The statistically significant predictors were changes in; the IPQ-R consequences subscale, salience, DAS24 and in perceived visibility (Table 4). The final model for changes in psychosocial quality of life accounted for 51% of the variance (F19 190=10.48, P<0.001). The statistically significant predictors were changes in; the IPQ-R consequences subscale, perceived visibility, social support from significant others and depression (Table 4).

Discussion

In line with previous research17, 18 strabismus surgery led to significant improvements in psychosocial and functional quality of life from preoperative assessment through to 3 months post surgery. No further improvements in quality of life were found at the 6 month follow-up, supporting previous research.11 Although improvements in psychosocial, but not functional quality of life, have been found up to 1 year post surgery,19 this does not negate the possibility that quality of life curtails 3 months after surgery. Contrary to what might be expected, improvements in functional quality of life were not associated with how successful surgery was from a clinical perspective. However, surgery deemed partially successful was found to be more psychologically detrimental, leading to a reduction in psychosocial quality of life from pre- to post surgery, than either success or failure, which both led to improvements in psychosocial quality of life. This contradicts other findings, which suggest small improvements in functional quality of life after failed surgery and larger improvements after both partial and successful surgery.20 The criteria used to define success and failure between these studies did however vary and could explain these differences.20

This study also provides unique evidence that strabismus surgery not only leads to improvements in quality of life, but also other psychosocial domains. The proportion of people with strabismus living with clinical anxiety or depression is considerably greater than that of the general population and those with chronic conditions,1 therefore a reduction in the number of patients meeting these criteria is an important step towards improving the mental health of this population. As a result of the restorative nature of strabismus surgery, it is unsurprising that patients perceived their strabismus as being less visible after surgery and felt more positive about their appearance, this appears to have enabled participants to feel more confident and less fearful of interacting and socialising with others, leading to reductions in social anxiety, and consequently improvements in quality of life.

Greater improvements in quality of life from pre- to post surgery was more likely in those who held more positive beliefs about their strabismus and treatment, experienced less social anxiety and social avoidance and had lower expectations about the outcome of their surgery pre-operatively. Although one might expect that targeting surgery towards those who are less able to cope would be more beneficial, these negative beliefs, high expectations and inability to socialise may impinge on the success of surgery. Being able to predict who will benefit most from surgery is clearly more complex than targeting those who appear more severely affected clinically or psychologically. Careful consideration therefore needs to be taken when listing patients for surgery who report more distress, as these patients maybe more likely to request further surgery as a result of not meeting high expectations for example, and may benefit from additional psychosocial support in order to optimise the benefits of surgery.

This study suggests that quality of life post surgery could be improved by addressing people’s beliefs about the negative consequences of their strabismus, challenging the value they place on appearance and how visible they think their squint is, as well as improving social skills. The evidence for improving the psychosocial well-being of people with a visible difference is at present weak, with more theoretically driven interventions, evaluated in RCTs, required.21 This could involve adapting and tailoring CBT-based or social skills interventions that have been developed and evaluated in people with a visible difference22 for the specific needs of people with strabismus.

The present study is limited by the lack of a randomised control group, which means that the changes observed from pre- to post surgery cannot be directly attributed to surgery. This is however unlikely given the significant psychological impact of living with strabismus, which is not predicted by disease duration.1

An appearance that differs from the norm can prove challenging in a society which is focused on appearance. Restorative surgery, such as ocular realignment, which reduces the perceived visibility and negative perceptions of one’s own appearance, may therefore provide a mechanism via which people feel better able to interact and cope in social situations, and hence reduces fear of negative reactions and social anxiety. It is however clear that not all experience these benefits despite successful clinical outcomes, therefore by intervening both psychologically and clinically the findings of this study may provide a unique mechanism via which the benefits of strabismus surgery can be optimised.

References

McBain HB, MacKenzie KA, Au C, Hancox J, Ezra DG, Adams GG et al. Factors associated with quality of life and mood in adults with strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 98: 550–555.

Gunton KB . Impact of strabismus surgery on health-related quality of life in adults. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2014; 25: 406–410.

Currie ZI, Shipman T, Burke JP . Surgical correction of large-angle exotropia in adults. Eye 2003; 17: 334–339.

Nelson BA, Gunton KB, Lasker JN, Nelson LB, Drohan LA . The psychosocial aspects of strabismus in teenagers and adults and the impact of surgical correction. J AAPOS 2008; 12: 72–76.

Burke JP, Leach CM, Davis H . Psychosocial implications of strabismus surgery in adults. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1997; 34: 159–164.

Liebermann L, Hatt SR, Leske DA, Holmes JM . Improvement in specific function-related quality-of-life concerns after strabismus surgery in nondiplopic adults. J AAPOS 2014; 18: 105–109.

Beauchamp GR, Black BC, Coats DK, Enzenauer RW, Hutchinson AK, Saunders RA et al. The management of strabismus in adults: the effects on disability. J AAPOS 2005; 9: 455–459.

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Liebermann L, Holmes JM . Comparing outcome criteria performance in adult strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology 2012; 119: 1930–1936.

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Liebermann L, Philbrick KL, Holmes JM . Depressive symptoms associated with poor health-related quality of life in adults with strabismus. Ophthalmology 2014; 121: 2070–2071.

McBain H, MacKenzie K, Hancox J, Ezra DG, Adams GG, Newman SP . What do patients with strabismus expect post-surgery? The development and validation of a questionnaire. Br J Ophthalmol 2015; 100: 415–419.

Jackson S, Morris M, Gleeson K . The long-term psychosocial impact of corrective surgery for adults with strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97: 419–422.

Larson SA, Keech RV, Verdick RE . The threshold for the detection of strabismus. J AAPOS 2003; 7: 418–422.

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Bradley EA, Cole SR, Holmes JM . Development of a quality-of-life questionnaire for adults with strabismus. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 139–144.

Leske DA, Hatt SR, Holmes JM . Test-retest reliability of health-related quality-of-life questionnaires in adults with strabismus. Am J Ophthalmol 2010; 149: 672–676.

Eliason SR . Maximum Likelihood Estimation: Logic and Practice. Sage Publications: UK, 1993.

Rubin DB . Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Vol 81. Wiley: UK, 2004.

Glasman P, Cheeseman R, Wong V, Young J, Durnian JM . Improvement in patients' quality-of-life following strabismus surgery: evaluation of postoperative outcomes using the Adult Strabismus 20 (AS-20) score. Eye 2013; 27: 1249–1253.

Jackson S, Harrad RA, Morris M, Rumsey N . The psychosocial benefits of corrective surgery for adults with strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 883–888.

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Liebermann L, Holmes JM . Changes in health-related quality of life 1 year following strabismus surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2012; 153: 614–619.

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Holmes JM . Responsiveness of health-related quality-of-life questionnaires in adults undergoing strabismus surgery. Ophthalmology 2010; 117: 2322–2328.

Bessell A, Moss TP . Evaluating the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for individuals with visible differences: a systematic review of the empirical literature. Body Image 2007; 4: 227–238.

Bessell A, Brough V, Clarke A, Harcourt D, Moss TP, Rumsey N . Evaluation of the effectiveness of face IT, a computer-based psychosocial intervention for disfigurement-related distress. Psychol Health Med 2012; 17: 565–577.

Acknowledgements

DE acknowledges funding by the Department of Health through the award made by the National Institute for Health Research to Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology for a Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McBain, H., MacKenzie, K., Hancox, J. et al. Does strabismus surgery improve quality and mood, and what factors influence this?. Eye 30, 656–667 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.70

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.70

This article is cited by

-

The Incidence and Risk Factors for Dry Eye After Pediatric Strabismus Surgery

Ophthalmology and Therapy (2023)

-

Association of mental disorders and strabismus among South Korean children and adolescents: a nationwide population-based study

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2022)

-

Shared decision making and patients satisfaction with strabismus care—a pilot study

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making (2021)