Key Points

-

Vocational training is a success for both trainers and vocational dental practitioners (VDPs).

-

Trainers are viewed as positive role models by their VDPs and trainers have a high opinion of their VDPs.

-

VDPs could not imagine entering general practice without undertaking vocational training.

-

VDPs enter vocational training as novice dentists; they leave as competent general practitioners.

Abstract

Aim To determine aspects of the 'lived experience' of dental vocational training (VT) for vocational dental practitioners (VDPs) and their trainers.

Design A qualitative study: semi-structured interviews were conducted with the participants halfway through VT and once the VT year had been completed.

Participants Two consecutive cohorts of 13 and 22 VDPs and their trainers.

Results The experience of VT for the VDPs and their trainers is presented together with a model of VDP progression through the VT year.

Conclusion VT is a success for VDPs and their trainers. Not one VDP would have wanted to enter general practice without VT. With very few exceptions the trainers considered VDPs capable of independent practice, post VT. Trainers were considered as positive role models by their VDPs. VT facilitates the transition of novice dentists into competent practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some form of immediate post-qualification training is now desirable for UK dental graduates. Most of the newly qualified will take the path to general practice. If they wish to practice within the general dental services (GDS) they must undertake a 12 month period of vocational training (VT) as a vocational dental practitioner (VDP) in an 'appropriate' dental practice or community clinic under the immediate supervision of a vocational trainer. The Dental Defence Agency has a parallel arrangement for new graduates wishing to enter the armed forces. Administratively, VT is divided into 15 regional deaneries. A regional advisor co-ordinates and monitors each of the schemes in that region. Each scheme, which consists of 12 training practices, is organised and similarly monitored by a VT advisor. The schemes can effectively be viewed as the functional units of VT. The regional advisor is usually one of the senior VT advisors in that region.

The study day

The VDPs are required to attend 30 study days during the VT year. These provide the formal educational component of VT and they are designed to complement the practice teaching. As well as an opportunity for formal teaching on all aspects of general dental practice, the study days are seen as an opportunity for VDPs to get together, share experiences and learn from each other. A questionnaire-based study by Bartlett et al. points to the study day as being a success.1 Only 17% of 435 VDPs did not find the day useful. Trainers are expected to attend 14 of the study sessions during the year. They also have trainer meetings. These are considered to be of paramount importance and they are arranged and facilitated by the VT advisor. The aim of these sessions is to monitor and review progress through the training year and they are normally held three times a year. These meetings provide a supportive framework for trainers, an opportunity to exchange views and ideas, help plan future course content and review feedback on VDP progress and curriculum content.2

The practice tutorial

As well as managing practice aspects of the VDP's professional development, the trainer is expected to devote at least one hour each week to tutorial tuition and the VDP keeps a record of these discussions in the professional development portfolio. The tutorial must take place during the working day and in protected time. This requirement remains in force for the entire duration of the training year.

The tutorial is seen as the backbone of in-practice teaching.

The professional development portfolio

In England and Wales this is the primary assessment tool in VT. The portfolio grew out of and superseded the VT record book that was the used in the early days of VT to monitor progress. Rattan2 notes that the portfolio reflects the shift in postgraduate education towards outcome based assessments. As part of the assessment process many, but not all, VT schemes require the VDP to present a case they have treated and/or undertake a clinical audit. That said, in England and Wales there is no formal assessment component in VT. Scotland has moved towards formal assessment in VT3,4 and there are many who are of the opinion that VT in England and Wales should follow suit. In fact Gibson5 has proposed an assessment process that leads the dentist leaving VT onto a clearly defined postgraduate path.

Background to present study

VT grew out of a profession-wide concern to provide a period of transition between student and professional life. Levine,6 working when VT was still optional, considered that this cushioned period of transitional education was essential for those entering general practice.

We have very little information on the lived experience of VT. From the same period as Levine's pre-compulsory VT work, we do have the brief personal accounts of D'Cruz. He has eloquently chronicled his experiences coming to terms with the very different learning regime in those first few weeks, post qualification.7,8 We also have a short account from Lester,9 D'Cruz's trainer. Significantly, in the final paragraph, Lester focuses on the VT relationship:

'There is a great deal to be said in favour of VT and when it works well, it works very well for trainers and trainees, but for its success it does need a level of commitment on both sides of the relationship.'

The Committee on Vocational Training10 did commission a review of VT. The study had a number of strands including a questionnaire circulated to all general dental practitioners in England and Wales (response rate 5.6%), three focus groups with interested parties and three in-depth practice staff interviews. The recommendations relevant to this present work were that VT should be mandatory for all dentists, the interface between undergraduate and postgraduate should be improved and there should be clear standards for assessment in VT and appropriate teacher education pathways for VT advisors and trainers.

Although significant and influential, what the review did not do was to identify the lived experience of VT.

Baldwin et al.11 noted that one third of a cohort of Scottish graduates did not consider their trainers as positive role models. Further, Ralph et al.12 reported that 30% of Leeds graduates had difficulty with the 'team', particularly their trainer who failed to provide support, encouragement and help. At present there is little evidence to support Seward's claim13 that VT has been the profession's success story. Indeed, Baldwin et al.11 commented:

'It is remarkable that no formal independent assessment of the value of VT [has ever been] carried out in terms of educational worth or... patient care.'

So what is VT like for the VDPs and what is it like for the trainers? The latter part of this question is something that is often ignored in commentaries on VT.

Methodology

The research questions

It is important, in fact essential, to be able to appreciate what is actually going on in VT. Aspinwall et al.14 pick up this very point and stress that it is essential to ask the question, how are we doing? Is VT achieving what it sets out to achieve? The General Dental Council, universities and VT personnel must have access to this information. Programmes of continuing professional development must be appropriate. VT aims to transform the novice dentist into a competent practitioner, but VT is a profound change for the new VDP. The expanded and overt environment of the university, and the compact, and comparatively clandestine world of general practice are very different learning environments. Does it work? Essentially the aim of this study was determine what actually happens in VT. Is Seward13 right? Is VT a success story for the VDPs? Is it a success for the trainers?

Participants in the study

Two consecutive cohorts of VDPs and their trainers were followed through their VT year. All the VDPs were graduates of King's College London Dental Institute. The cohorts were taken from qualifying years where approximately 70-75 of the new dental graduates went directly into VT. The first cohort consisted of 13 VDPs and their trainers; the second, 22 VDPs and trainers. In the initial cohort there were 11 female and two male VDPs and in the second, 16 and six respectively. This bias towards females is somewhat greater than that of the intake of the Dental Institute generally, where the proportion is closer to 60%. The VDPs were, however, chosen simply on the basis that, aware that this study was taking place, they showed an interest in taking part.

Although all of the training partnerships were located in Southern England, geographically these partnerships stretched as far west as Poole in Dorset and as far north as Northampton, and were positioned in 21 VT schemes across five regional deaneries.

The trainers of both cohorts were effectively selected by the VDPs. Although around 60% of new graduates are women, this has yet to manifest itself in VT and training is still a male dominated preserve. Three of the 13 trainers in the initial cohort and five of the 22 in the second cohort were female. One of the female trainers in the second cohort shared the training of her VDP with a male colleague; there were two other training practices where training was shared. There was no shared training in the initial cohort. Every trainer contacted was willing to participate in the study.

The VDPs chose the location for their interviews. Most VDPs were comfortable for the interviews to take place in their training practices, but interviews were conducted in varied locations including coffee shops and fast-food restaurants. All of the trainer interviews were conducted in the training practices.

The strategy

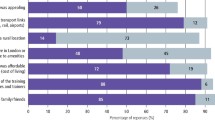

Following the advice given by Aspinwall et al.14 for the development of success criteria, VT performance areas at both practice and regional level were identified for criteria development. Focusing questions for each of the performance areas were devised and semi-structured interview schedules developed for the VDPs and trainers. Included were appropriately modified schedules for trainers who were also VT advisors. The performance areas used in the interview schedules are presented in Figure 1.

Once the cohort was settled in VT, ie after approximately five to six months, each of the VDPs was individually interviewed. A further interview was conducted once they had completed the VT year. The trainers involved in the training of the VDPs were also interviewed. These interviews took place immediately or shortly after the VDP interviews. As with the VDPs, the trainers were re-interviewed at the end of the VT year. The durations of each of the interviews varied but most were between 45 minutes and one hour.

Results

The 35 trainers who participated in this study had been qualified for a mean of just over 21 years, the individual cohort means being remarkably similar at 21.3 and 21.7 years for the first and second cohorts respectively.

The trainers had taught on average five VDPs, again the mean for the second cohort was slightly higher than the first at 5.1 and 4.8 respectively. In both cohorts the range of training varied from the VDP in this study being the trainer's first, to trainers who had seen in excess of 10 VDPs. Some had been in VT since the early non-mandatory days.

The first six months

As far as their role in VT was concerned, 30 trainers (86%) saw this as providing guidance, easing the transition of the VDP into general practice and being a mentor. However, one trainer suggested his task was to teach basic skills – skills that he felt ought to be in place on qualification.

Into VT, there was only one VDP who was not satisfied with the clinical facilities that were made available to him. The VDPs' patient loads once they were settled in ranged from 15-25 patients a day, with a mean closer to 15 than 25. As time went on and they became more efficient, significantly 18 of the VDPs (51%) noted that the number of patients they saw didn't necessarily increase, but the amount of work carried out on each patient did.

The VDPs' opinions on the quality of their nursing support depended on which cohort they were in. In the first cohort there were six negative views (46%) and only four positive views (31%). In the second cohort there were four negative (18%) and 14 positive views (64%). Throughout both cohorts, the most experienced trainers were more likely to ensure that the VDP had an experienced nurse, even if that meant that the trainer went without one him/herself. The nurse was constantly at the VDP's side and was in a position to identify and defuse or report potential problems before they became major issues.

On starting VT, 15 of the VDPs (43%) were concerned about the workload they were likely to face and the possibility of running late. Twelve (34%) were worried about living up to expectations. In those early days, 32 of the VDPs (91%) reported that their trainer was supportive and always there when he/she was needed. Two VDPs (6%) were disappointed with the support they received at this time.

In the first six months, 21 of the VDPs (60%) reported that they had regular one-hour tutorials and these took place in protected time. Apart from the early housekeeping sessions, the tutorials invariably had a clinical bias. Nine of the VDPs (26%) reported that it was quite common for the trainer to use this session as an opportunity to carry out a clinical procedure on a patient together with his/her VDP. Managing the tutorial in this manner was very popular with the VDPs.

As far as the trainers were concerned, 14 (40%) suggested that the tutorial session was used to discuss issues of the day/week. Those who made this comment had taught a mean number of 4.6 VDPs, with a range of one to ten. Eight trainers (23%) suggested that they tried to make the VDP take the lead in the tutorial; in fact, take responsibility for their own education. It was the most experienced who made this comment; they had taught a mean number of 7.9 VDPs, with a range of five to 11. Using the tutorial session to treat a patient with the VDP was suggested by eight trainers (23%). Interestingly, these trainers were relatively inexperienced and had taught a mean of just 2.5 VDPs with a range of one to five.

Trainers had the almost universal view that as far the first half of the year was concerned, in the first three months the VDPs needed a lot of help and the second three months was a settling in period. Fifteen of the trainers (43%) suggested that from the halfway point onwards it was essential to stand back and give the VDP space. The mean number of training years possessed by this group was 6.1 with a range from one to 11.

After the first six months, 25 trainers (71%) suggested the basics should be in place; four (11%) specifically noted that they would expect the VDPs to have a working knowledge of the NHS regulations. Twenty-four of the trainers (69%) noted that it was now that the VDPs could start to work more efficiently.

In those first six months, 33 of the VDPs (94%) reported that they were getting quicker, and performing a broader range of tasks. They confirmed that they were not necessarily seeing more patients, but doing more on each. Thirteen (37%) of the VDPs specifically noted that their treatment planning had improved and, confirming the expectation of their trainers, they were able to manage patients with enhanced efficiency.

As far as the study days were concerned, 18 VDPs (51%) commented favourably, 13 (37%) had mixed feelings and six (17%) did not enjoy them at all. That said, as a forum for the scheme members to get together, exchange ideas and share problems it was very successful and appreciated by all the VDPs. All advisors were trainers (on different schemes to their own). Only five VDPs (14%) spoke positively when asked about their relationship with their advisors. One particular advisor (a trainer in this study) was regarded most highly by the successive VDP cohorts. Interestingly, he stressed how important it was for all parties to work at making the year a success. Where there were problems, the recurring theme was that VDPs were unhappy with the way they were managed by their advisor. The advisors' organisational skills were never an issue.

Fewer trainers specifically addressed the issue of the study day. Overall, four (11%) were very positive and thought the study days very worthwhile. Six (17%) were a little more cautious with their remarks; two (6%) were very uncomplimentary. Eight trainers (23%) thought the study days were an excellent opportunity for the VDPs to meet their peers and share their experiences, a sentiment echoed by 18 (51%) of the VDPs. Five trainers (14%) volunteered that they were unhappy with the private bias of some of the study day lecturers and indeed with what they considered was a bias towards private dentistry in VT.

The portfolio did not fare particularly well. An issue only discussed with the second cohort, only one of the 22 VDPs thought it useful. Seventeen (77%) suggested it was either not useful or a waste of time. The adjective most often used to describe the portfolio was 'tedious'. Three VDPs (14%) reported that their trainers and advisors checked it regularly. The trainers and advisors belonging to seven (32%) of the VDPs had not looked at it at all in the first six months of training.

As far as the trainers were concerned, 12 (55%) thought the portfolio served a purpose, but there were problems with it. Four (18%) suggested that it was an excellent assessment tool if used properly. Interestingly, these four trainers had a very high mean of 8.25 training years, the range from six to 10. Five trainers (23%) did not consider the portfolio at all useful.

The second six months

Eight (62%) of the first cohort of VDPs reported that the tutorials continued throughout the year, but eight (62%) of this cohort also noted that the tutorials tended to become far less regular than they had been in the first half of the year. Twelve (55%) of the second cohort had tutorials that continued to the end of the year, but 10 (45%) of this cohort noted a reduction in the regularity of the tutorials. One VDP did not have any tutorials in the first three months, but thereafter they continued to the end of the year. The most experienced trainers, those who in the first six months had made the VDPs take responsibility for their own education, were the most likely to continue the tutorials right to the final week of VT. But the nature of the tutorials changed, with these trainers reporting that they were more reflective in nature.

Reflecting on their nursing support during the second half of the year, if anything the VDPs' comments were less favourable than at the half way stage. Six (46%) of the first cohort and 14 (64%) of the second cohort were satisfied. Unfortunately seven (54%) of the first and eight (36%) of the second cohort were particularly unhappy with the support that they had received. Not having a nurse in this period or having to train up an inexperienced nurse were major reasons for this downward trend. Another was a nurse's inability to adequately support the VDP when he/she felt able to speed up and increase workload.

It was pleasing to discover that 27 (77%) of the VDPs viewed their trainers as a positive role model. Four (11%) had mixed feelings about their trainers and for four others (11%) their trainer was not a positive role model.

Reflecting on the year as a whole, nine (26%) of the VDPs had some, usually relatively minor reservations; 26 VDPs (74%) thought the year had gone well. None would have wanted to enter practice without VT. For the trainers, 28 (80%) thought that the year had been a success. Six (17%) still harboured reservations either about their VDPs or how the year had progressed, while one trainer was particularly unhappy with the conduct of her VDP throughout and did not consider the year a success.

The process of trainer selection was not an area included in the interview schedule, but five (23%) of the second cohort trainers voiced their concern that possessing additional qualifications was becoming ever more important, even though this did not necessarily indicate how good a trainer a practitioner was. One of these trainers had himself undertaken relevant postgraduate qualifications to secure his training position, but he expressed his concern that excellent trainers were likely to be lost to VT if the possession of additional qualifications became mandatory.

At the end of VT, four (31%) of the first cohort stayed on as an associate in the training practice, one part-time. Five (23%) the second cohort stayed, one in a part-time capacity. In two partnerships in the first cohort (15%) and five (23%) in the second cohort, both VDP and trainer regretted that they did not continue working together at the end of VT.

What these figures do not show is the close friendships that developed within many, in fact most of the training partnerships. Four, now former VDPs (11%), specifically noted that although VT was behind them and they were now in associate positions, their 'old' trainer was the first person they called if they had a problem. Three former VDPs (9%) continued to attend postgraduate meetings with their trainer. One associate concerned that in her quest to enhance efficiency, her clinical standards were suffering, contacted her former trainer. He found time for her to return to his practice part time and re-establish her clinical standards.

Discussion

While some were more successful than others, all the training partnerships reached a conclusion, and for the overwhelming majority that was a successful conclusion. The 'average' trainer in this study tended to have significant training experience. He/she was likely to have been qualified for over 20 years and had already taught five VDPs.

It is pleasing to note that the clinical facilities afforded to the VDPs were, with but one exception, entirely satisfactory. Unfortunately the nursing support was very variable. The most experienced trainers, however, ensured that their VDPs had a skilled nurse – often the best or most experienced in the practice. They realised that such a person is able to monitor VDP progress far more closely than the trainer is able to. She/he can act as a first line of defence against potential problems and is in a position to defuse situations almost before they arise.

As the year progressed, if anything the VDPs became less satisfied with their nursing support. Not having a nurse or having to train up an inexperienced nurse in the second half of the year was not uncommon and was seen as a major problem. During this period the VDP is looking to speed up and increase workload. The situation becomes more problematic for the VDP as this is the time that the trainer encourages him/her to work with greater efficiency.

Excellent support was afforded to the VDPs by the vast majority of trainers in the first days and weeks of VT. Two trainers, who fell short in this respect, were both in their first year of training and perhaps had unrealistic expectations of the competence and needs of the new graduate. This is not surprising. It takes time for the trainer to immerse him/herself into the culture of VT. It takes time to appreciate what the new graduate is capable of.

The practice tutorial is mandatory, yet only 21 VDPs (60%) reported that they had regular tutorials in the first six months. As the year progressed, if anything the regularity of the tutorials decreased – although for the most part, they did continue to the end of the year. Again it was interesting to see that the most experienced trainers always continued the tutorials to the end of the year, but the focus changed and it seems to be entirely appropriate that these became more reflective at that time.

There were many aspects of a relationship that influenced the outcome, and the experience, perhaps expertise, of the trainer was an obvious one. It is perhaps significant that the trainers who in their teaching, were able to create an atmosphere conducive to professional development; the trainers who made the VDPs take the lead and/or assume responsibility for their own teaching, had taught for a mean of 7.9 years.

The VDPs' comments regarding the study days were not as favourable as those regarding their trainers and the practices. The ability for the VDPs to meet and share experiences is the study day's reason to be and it was pleasing to note that this aspect of the day was a great success. To know that you are not alone and others in your scheme have exactly the same problems and concerns is invaluable.

Some study day teaching does have a private dentistry bias. Whether this is appropriate in a fully NHS-funded system of education is not for discussion here. What is, however, is the fact that VDPs want something on the Friday (when most study days occur) that will help with their practice on Monday morning. There is an immediacy about their need, and perhaps the content and structure of some study days should be reviewed.

It was disappointing to see that the VDPs' relationships with their advisors were not necessarily as successful as those with their trainers. Managing a VT group is a specific skill and this must be appreciated. Significantly, the popular advisor had echoed Lester's comments;9 he stressed the importance of all parties working to make the year a success. These findings regarding the study day would appear to run contrary to the earlier work of Bartlett et al.1 That said, whereas their study noted that only 17% of VDPs did not find the study days useful, it is possible that the highly positive social component was compensating for other less popular aspects of the day.

The portfolio is excellent if used skilfully. Some of the very experienced trainers grounded their teaching within the structure of the portfolio, but this opportunity to develop ongoing and meaningful assessment was, for the most part, lost. Perhaps it is time to reinstate the professional guidance in its use that was available in the early days of VT.

Having 27 VDPs (77%) view their trainer as a positive role model is very pleasing to record and this runs contrary to the findings of Baldwin et al.11 and Ralph et al.12 It is difficult to explain such a difference. The participants in the study were a self-selecting group with a strong female bias. This could have had an influence on their perception of the 'lived experience' of VT as being 'better.' It could also be that education and training in VT is continuing to move forward. Significantly, not one of the VDPs could imagine going into general dental practice without VT, and that includes, of course, the few who did not really get on with their trainer.

As far as the trainers are concerned, it is easy to pick up on the six (17%) who had reservations regarding the year and/or their VDP. But only one thought the year had been a failure; 28 (80%) thought it had been a success. It was pleasing to see the relations that developed post VT. Not many VDPs stayed on as associates in their VT practice, but there was so much more to the story of the VT year. The idea that some still regretted parting company, the fact that those who were now associates still felt comfortable calling their trainer for advice, speaks volumes with regard to the less tangible benefits of the year.

A model of progression

Through the conversations with the trainers it was clear that each had a quite tightly defined notion of VDP progression and they had developed a model of progression through VT. Figure 2 summarises the VDPs' progress through the year. After a period of trepidation, anticipating the start, the students begin VT and enter the honeymoon period. This lasts about four to eight weeks. They then enter the blue period; a time when they are likely to need encouragement. The reality of practice hits home. The VDPs then start to fret about their novice status. Into the New Year (five to six months in) it gets better. Twenty-five (71%) of the trainers specifically noted that the basics are now in place and the VDPs are more positive about the experience. They are perhaps now moving away from their novice status. The final six months is a period for gaining confidence, speed and efficiency. The VDPs are showing signs of becoming competent general practitioners.

Conclusion

The aim of VT is to facilitate the transition of new graduates into general dental practice, or turn novice dentists into competent practitioners, and this study considered defined aspects of VT to determine that aim. To confirm Seward's assessment,13 VT is a success story. It is a success for VDPs and it is a success for trainers. VT is not perfect; there are problems, but it is important to put these in perspective. The overwhelming majority of the partnerships saw the year as a success. VDPs also enjoy VT. It is hard work, but none would have wanted to enter general practice without it.

Trainers do a good job and they have for the most part, a high opinion of the VDPs in their care. Many in VT feel that formal assessment is necessary and have proposed a structured assessment process.5 Do VDPs and trainers need it? VDPs are novices and that must be remembered. In this study it appears that trainers skilfully identified the VDPs' weak areas and more often than not remedial action was taken with a minimum of fuss. The portfolio is of high quality and points the way forward in the VDPs' continuing professional development. But for the portfolio to be a success, all VT personnel must value it and be committed to its use.

As for the concerns of Baldwin et al.11 about patient care, with very few reservations, trainers were of the opinion that VDPs were capable of independent practice post VT. We need not be concerned about the educational worth of VT. Trainers assumed the role of professional teachers, during and beyond VT, and they carry out these duties to a high standard. VT is not perfect and fine tuning is necessary. But major change to the organisation, management and assessment should be avoided. This study did of course consider VDPs from one London School all of whom undertook VT with trainers in Southern England. But it was a large area of Southern England and nothing in the conversations with the practitioners suggested to the authors that the experience of VT should be significantly different elsewhere. VT works and it works well; VT facilitates the transition of the novice dentist into a competent practitioner.

References

Bartlett D W, Coward P Y, Wilson R, Goodsman D, Darby J . Experience and perceptions of vocational training reported by the 1999 cohort of vocational dental practitioners and their trainers in England and Wales. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 265–270.

Rattan R . Vocational training in general dental practice: a handbook for trainers. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2002.

Grieveson B . Assessment in dental VT... can we do better? Br Dent J 2002; 193 (Suppl) (Sep): 19–22.

Prescott L E, Norcini J J, McKinlay P, Rennie J S . Facing the challenges of competency based assessment in postgraduate dental training. Longitudinal evaluation of performance (LEP). Med Educ 2002; 36: 92–97.

Gibson C J . The assessment of dental vocational training; a personal view. Dent Update 2005; 32: 552–555.

Levine R S . Experience, skill and knowledge gained by newly qualified dentists during their first year of general practice. Br Dent J 1992; 17: 97–102.

D'Cruz L . The first day. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 53–54.

D'Cruz L . The day-release course. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 85.

Lester D . The trainer's story. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 128.

Committee on Vocational Training for England and Wales. The review of vocational training in dentistry for the Chief Dental Officers, England and Wales. London: The Committee on Vocational Training for England and Wales, 2002.

Baldwin P J, Dodd M, Rennie J S . Postgraduate dental education and the new graduate. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 591–594.

Ralph J P, Mercer P E, Bailey H . A comparison of the experiences of newly qualified dentists and vocational dental practitioners during their first year of general dental practice. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 101–106.

Seward M . Dental education in the 21st century. Primary Dent Care 2000; 7: 5–7.

Aspinwall K, Simkins T, Wilkinson J F, McAuley M J . Using success criteria. In Preedy M, Glatter R, Levicic R (eds) Education management: strategy, quality and resources. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1997.

Acknowledgements

The demands in terms of time made on those who participated in this study were considerable. Not one VDP or trainer declined to be interviewed. In fact, each gave very generously and freely of his/her time and made the interviewer (LBC) very welcome. We thank them for their help with this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cabot, L., Patel, H. Aspects of the dental vocational training experience in the South East of England. Br Dent J 202, E14 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.78

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.78

This article is cited by

-

Post-qualification dental training. Part 2: is there value of training within different clinical settings?

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Dentistry – a professional contained career in healthcare. A qualitative study of Vocational Dental Practitioners' professional expectations

BMC Oral Health (2007)

-

Dental vocational training: identifying and developing trainer expertise

British Dental Journal (2007)

-

Dental vocational training: some aspects of the selection process in the South East of England

British Dental Journal (2007)