Abstract

Purpose

To suggest a surgical approach that would pre-empt uncontrolled posterior capsular rupture and consequent posterior segment complications associated with posterior polar cataract surgery.

Design

An interventional case series.

Methods

This was a prospective, interventional study undertaken at a tertiary referral ophthalmic unit. Eleven eyes of eight patients underwent planned pars plana vitrectomy, lensectomy and posterior chamber sulcus fixated intra-ocular lens implantation. Demography, presenting features, pre- and post-operative visual acuities, complications and length of follow-up were recorded. A single surgical technique was performed in all the cases.

Results

Five male and three female patients with a mean age of 49.7 years, underwent this procedure. The median-corrected pre-operative visual acuity was 6/12 and the same post-operatively was 6/6. The only major per-operative complication was one case of accidental iridectomy. Post-operatively there were transient choroidal folds in one case, mild posterior segment haemorrhage in another and retinal detachment in one patient. The mean follow-up period was 13 months.

Conclusions

This surgical technique offers a relatively controlled and predictable approach to posterior polar cataract surgery compared to others described in the literature. Although this technique is not without complications, the visual outcome is usually good.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital posterior polar cataract is a localised central sub-capsular opacification of the crystalline lens. This particular morphology makes cataract surgery a challenging procedure, because the posterior capsule adjacent to the opacity tends to be weak.1, 2

Various techniques have been suggested to minimise the risk of posterior capsular rupture during cataract extraction.3, 4 Despite these, Osher et al5 report 26% and Vasavada et al6 report 36% incidence of capsular rupture in two of the largest series. Recent studies with newer techniques have reported much lower complication rates,7, 8 but the risk of posterior capsular rupture in an uncontrolled environment remains.

This prospective study looks at pre-empting the problem of uncontrolled posterior capsular rupture by performing planned pars plana vitrectomy, lensectomy, and posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation.

Design

This was a prospective, single centre study, which had ethical approval. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Methods

Between 2001 and 2003, 11 eyes of eight patients with congenital posterior polar cataracts were operated on by a single surgeon. The diagnosis of posterior polar cataract was confirmed by the surgeon before surgery by slitlamp biomicroscopy. The case notes of these patients were reviewed.

Preoperative data included presenting symptoms and visual acuity, demography and laterality.

Operative data consisted of type of surgery and per-operative complications. Post-operative complications, length of follow-up and final visual acuity were also noted.

Surgical technique

A routine planned pars plana vitrectomy was performed. This procedure included a limited peritomy for the entry ports. Three self-sealing scleral ports were fashioned with a crescent and an MVR blade. The infusion line was secured to the lower temporal port with a 5/o Ethibond suture and closed off. A 19-gauge winged metal infusion canula (‘butterfly’) was then used as an infusion line directly into the crystalline lens. The MVR blade was then inserted into the crystalline lens and either the vitrector cutter or the fragmatome or both (depending on nuclear sclerosis) used to remove the lens. Efforts were made to preserve the capsular beg intact for as long as possible, but in all cases some lens fragments were dislocated posteriorly. The anterior capsule was left intact at this stage.

The infusion line was then switched on after removing the ‘butterfly’ and a routine central vitrectomy performed. In very young patients the posterior hyaloid was deliberately not peeled and in older patients this was carried out when possible. Any remaining lens fragments were removed. Sometimes during this part of the procedure, anterior capsular opacification would occur, in which case the vitrector cutter was used on suction mode to clean the posterior surface of the anterior capsule. The retina was then inspected for presence of retinal tears and cryotherapy applied when required. With the infusion switched off, the anterior chamber was then opened with a 3.5 mm keratome and filled with viscoelastic. A foldable posterior chamber Silicone intraocular lens was inserted and dialled so that the haptics were vertical, thus being placed in the ciliary sulcus anterior to the anterior capsular ledge. The viscoelastic was then removed. A central anterior capsulotomy was then made via the pars plana using the vitrector cutter.

The conjunctiva was sutured with 8/o vicryl and a subconjunctival injection of steroid and antibiotic was given.

Results

There were five males and three females with posterior polar cataracts, with a mean age of 49.7 years (range, 12–68 years). Four of these patients had been noted to have bilateral posterior polar opacities. Of these, three had bilateral cataract surgeries. All the patients had presented with deterioration of visual acuity.

One patient had a family history of posterior polar cataracts, with the mother and sister suffering from the same condition.

All the eyes had pars plana vitrectomy, lensectomy, and sulcus fixated intraocular lens implantation. Three eyes had Pharmacia 911A Silicone IOL and eight had Allergan S1 140NB Silicone IOL implants.

Per-operative complications included one case of bleeding from accidental iridotomy and two cases of small posterior segment haemorrhage, one from the accidental iridotomy and the other from an entry site. Three young patients required a single 10/o nylon suture to secure the corneal wound.

Post-operative complications included one case of retinal detachment 2 months post-operatively and one patient had choroidal folds for 3 weeks owing to hypotony, which resolved spontaneously. One patient had pupillary capture with the inferior margin of the IOL. This resolved with the use of topical miotic drops and posturing the patient in a supine position.

The median corrected pre-operative visual acuity was 6/12 (range, 1/60 –6/9) and the median corrected post-operative visual acuity was 6/6 (range, 6/6–6/12). The post-operative visual acuity was significantly better. Post-operative improvement in visual acuity was comparatively less in one case, which had developed retinal detachment.

The mean follow-up period was 13 months (range, 7–24 months) Table 1.

Discussion

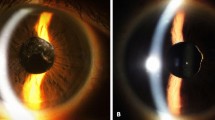

Congenital posterior polar cataract is a localised central sub-capsular opacification of the crystalline lens. It consists of a very white, well-demarcated, opacity located in the centre of the posterior capsule,9 often looking like a pile of small white discs of decreasing size projecting forward into the posterior lens cortex. (Figures 1 and 2) This appearance is completely different from a localised plaque of posterior subcapsular opacity. However, posterior sub-capsular opacity often forms around a posterior polar cataract and is the usual cause of presentation with decreased visual acuities.

Most of these cataracts have an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern,10 although occasional sporadic cases have also been noted. Electron microscopy has shown that there is accumulation of abnormal lens fibres and extracellular materials. The plaque is acellular and is strongly adherent to the posterior capsule centrally. These cataracts show a breakdown of lens fibres, presence of disorganised lobules and membranous whorls and a weakness or deficiency in the posterior capsule11 (Figure 3).

Posterior polar cataracts form a group that poses a challenge to the cataract surgeon because of the risk of per-operative capsule rupture potentially resulting in vitreous loss and retained lens material. This is due to the weakness of the capsule around the opacity.1, 2 There is also a suggestion in the literature that the capsule may actually be deficient in the area of polar opacity.12

Extraction of a posterior polar cataract should be performed in a way that minimises the risks of posterior segment complications and maximises the benefits of posterior chamber IOL implantation.13 Various techniques have been described previously, which essentially aim to protect the posterior capsule around the polar opacity by, for instance, visco-disection of epinucleus, and cortex13 or gentle irrigation and aspiration of epinucleus with removal of the plaque right at the end.14

Hayashi et al15 reported two cases of pars plana lensectomy in their series. A recent publication has quoted 11% posterior capsular rupture rate using careful controlled hydrodelineation and a modified ‘lambda’ technique of phacoemulsification.7 The most recent technique advocates bimanual microphacoemulsification as an effective way of reducing complications.8

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to look prospectively at the option of routinely performing pars plana vitrectomy and lensectomy. This eliminates the risks of unexpected capsule rupture and posterior segment complications, and provides a controlled approach to posterior polar cataract surgery, although caution should be exercised in its use in view of the significant associated complications.

Visual improvement was significant in most cases. One patient that comparatively did not do well had developed a retinal detachment two month post-operatively. He underwent retinal re-attachment surgery and the retina remained attached at the last post-operative visit.

In conclusion, posterior polar cataract can be operated on by various surgical techniques, the choice of which may depend on the surgeon. The preferred option would be cautious conventional phacoemulsification with careful hydrodelineation and ‘in the bag’ IOL implantation by an experienced surgeon. However, an individual cataract surgeon may well have a greater than 30% capsule rupture rate because of the rarity of this condition and the lack of individual experience. Patients having unexpected complications of this type often require subsequent additional surgery by a posterior segment expert, with consequent increased anxiety for all concerned. Although the technique discussed here is not without complications, the results are generally good and caution should be exercised in its use in view of the significant associated complications.

References

Skalka HW . Ultrasonic diagnosis of posterior capsular rupture. Ophthalmic Surg 1977; 8: 72–76.

Hiles DA, Chotiner B . Vitreous loss following cataract surgery. J Paediatr Ophthalmol 1977; 14: 193–199.

Arshinoff SA . Dispersive-cohesive viscoelastic soft shell technique. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999; 25: 167–173.

Fine IH . Cortical cleaving hydrodissection. J Cataract Refract Surg 1992; 18: 508–512.

Osher RH, Yu BC-Y, Koch DD . Posterior polar cataracts: a predisposition to intraoperative posterior capsule rupture. J Cataract Refract Surg 1990; 16: 157–162.

Vasavada AR, Singh R . Phacoemulsification in eyes with posterior polar cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999; 25: 238–245.

Lee MW, Lee YC . Phacoemulsification of posterior polar cataracts – a surgical challenge. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87: 1426–1427.

Haripriya A, Aravind S, Vadi K, Natchiar G . Bimanual microphaco for posterior polar cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006; 32: 914–917.

Duke-Elder S . Posterior polar cataract. System of Ophthalmology, vol III, part 2. Normal and Abnormal Development, Congenital Deformities. CV Mosby: St Louis, MO, 1964; 723–726.

Nettleship E, Ogilvie FM . A peculiar form of hereditary congenital cataract. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1906; 26: 191–207.

Eshajian J . Human posterior subcapsular cataracts. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1982; 102: 364–368.

Hejtmancik JF, Datilles M . Congenital and inherited cataracts. In: Tasman W Jaeger EA (eds). Duane's Clinical Ophthalmology, CD ROM edn Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, 2001, vol 1, chapter 74.

Fine IH, Packer M, Hoffman RS . Management of posterior polar cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003; 29: 16–19.

Allen D, Wood C . Minimising risk to the capsule during surgery for posterior polar cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002; 28: 742–744.

Hayashi K, Hayashi H, Nakao F, Hayashi F . Outcomes of surgery for posterior polar cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003; 29: 45–49.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghosh, Y., Kirkby, G. Posterior polar cataract surgery – a posterior segment approach. Eye 22, 844–848 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702743

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702743